Geological history of the Precordillera terrane

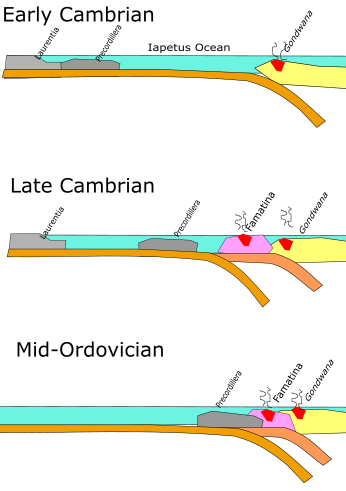

The Precordillera terrane of western Argentina is a large mountain range located southeast of the main Andes mountain range. The evolution of the Precordillera is noted for its unique formation history compared to the region nearby. The Cambrian-Ordovian sedimentology in the Precordillera terrane has its source neither from old Andes nor nearby country rock, but shares similar characteristics with the Grenville orogeny of eastern North America. This indicates a rift-drift history of the Precordillera in the early Paleozoic. The Precordillera is a moving micro-continent which started from the southeast part of the ancient continent Laurentia (current location: North American Plate). The separation of the Precordillera (also named Cuyania[1]) started around the early Cambrian. The mass collided with Gondwana (the ancient supercontinent in the southern hemisphere) around Late Ordovician period. Different models and thinking of rift-drift process and the time of occurrence have been proposed.[2][3][4] This page focuses on the evidence of drifting found in the stratigraphical record of the Precordillera, as well as exhibiting models of how the Precordillera drifted to Gondwana.

Location

Precordillera is a Spanish geographical term for hills and mountains lying before a greater range. The term is derived from cordillera (mountain range)—literally "pre-mountain range"—and applied usually to the Andes.[5]

The Precordillera is in western Argentina and can be traced by the thrust-fold belt.[6] It is about 200 km wide, and stretches 800 km from latitude 29°S to 33°S in western Argentina, with its south end in Mendoza, through San Juan, to La Rioja in the north. The northern and southern boundaries are not precisely defined.[7]

In terms of geological regions, the northeastern boundary connects to the western Pampeanas and the Famatina ranges, and the eastern margin connects to the frontal Cordillera then the Chilenia Terrace.[7]

Evidence of rifting

Stratigraphic records

The Early-Cambrian to Ordovician deposits of Precordillera are composed of 3000 m thickness of marine carbonate sections with multiple phases of grain size variation. The Precambrian Precordillera basement is Grenvillian-type and the Cambrian-Ordovician layer is uniquely found in Precordillera compared with surrounding Andes and Sub-Andes belt.[8]

The sedimentary deposit in Precordillera is recognized as "typifying low-latitude stable passive-margin continental terrace deposits".[8] That means Precordillera was transformed from thermal continental margin subsiding to passive margin. The facies types of Cambrian-Ordovician carbonate deposit in Precordillera matches the Southern Appalachian platform, suggesting the origin of Precordillera from Laurentia.[8]

The Precordillera formation ranging from Early Cambrian to Late Ordovician would be introduced as follows:[7][9]

Cerro Totora Formation (Early Cambrian)

The Cerro Totora Formation with a thickness of 340 m contains red marine sandstone and siltstone at the lower section. At upper section, the red evaporites are interbedded with carbonate sandstone and siltstone. At the top of the formation, quartz arenites present indicate the upper boundary of the Cerro Totora Formation.[9] The evaporites and red sedimentary rock indicate the transition from syn-rift development to the ending of rifting. The upper formation comprises Early Cambrian olenellid trilobites which indicates the region was a normal marine environment.[9]

La Laja Formation (Early to Mid Cambrian)

The 525 m thick La Laja formation is a thick layer of progradational carbonate complex. The base is composed of a fine grained lime mudstone which contains fossils of olenellid trilobites and phosphatic brachiopods.[9] Higher in the layer, the carbonate contain larger grains, so that the carbonates are described as oolitic limestone or grainstone. Overall the sediment shows a couple of depositional conditions – from fine grain mudstone forming in an open marine environment to increasing grain size of grainstone, oolitic limestone in a shallow marine environment.[9]

Zonda and La Flecha Formation (Middle to Late Cambrian)

The Zonda (200-300 m thick) and La Flecha Formation (400-700 m thick) starts from the continuous layers of La Laja Formation limestone to peritidal dolomite.[9] They show a total of three sequences of shallowing-upward features, one shoaling upward sequence in the Zonda formation and two in the La Flecha Formation. It is described as aggradational carbonate complex because of insignificant lateral sift of deposits. From this point the terrace was undergoing the drifting process, traveling from Laurentia to Gondwana. Also abundant distributions of thrombolites dominate each basal sequence and become less significant in the uppermost intervals.[9]

La Silla Formation (Early Ordovician)

The La Silla Formation (400 m thick) is the start of Ordovician deposits. It shows depositions of subtidal carbonate mudstone and wackestone which is sandwiched by peritidal carbonates. The formation lacks erosion features as well as terrestrial deposits, indicating an open-marine environment. Models deduced that the Precordillera terrace had been travelling through the Iapetus Ocean approaching the Gondwana supercontinent.[9]

San Juan Formation (Mid Ordovician)

The San Juan Formation (330 m thick) continues as a carbonate deposit of packstone, grainstone, wackestone, and mudstone. It shows two transgressive system tracks indicating drowning events, or in other words the eustatic rise of sea level. The significant reef accumulations can be found in two intervals – the packstone at the boundary above La Silla Formation, and during the sudden change from marine environment to shallow-water grainstone.[9] As sea level rises, fine and dark mudstone and shale deposit as an indication of approaching the subduction zone beneath Gondwana.[9]

Late Ordovician unconformity

The sedimentary records no longer continuous on top of the San Juan Formation, and it is marked as an erosional unconformity. On top of the black shale the eastern Precordillera crust received a continental rise, inducing the rapid intensive events shown by the rifting structure on the deposits above the unconformity. The western basin consists of black graptolitic shale with non-constant thickness which contains silicate clasts, believed to be a kind of rifting-related deposit.[9] The unconformity symbolizes the increasing tectonic activity, probably the start of rifting events and the collision between Precordillera and Gondwana.

| Formation | Age | Thickness | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erosional unconformity – extensional rifting | |||

| San Juan Formation | Middle Ordovician | 330 metres (1,080 ft) | Two trangressive sequences of carbonates. Reef accumulations in shallow deposits |

| La Silla Formation | Early Ordovician | 400 metres (1,300 ft) | Subtidal carbonate sandwiched by peritidal carbonates. Without detrital deposition. |

| Zonda and La Flecha Formations | Late Cambrian | 600–1,000 metres (2,000–3,300 ft) | Aggradational peritidal dolomites |

| La Laja Formation | Early to Middle Cambrian | 525 metres (1,722 ft) | Progradational carbonate complex with olenllid trilobites |

| Cerro Totora Formation | Early Cambrian | 340 metres (1,120 ft) | Red sandstone and evaporites |

Trilobites

The olenellid trilobites found in early Cambrian sequences are identical to those in the fragments in Laurentia. The similar fossil records have contributed greatly to the hypothesis that Precordillera was linked to Laurentia until Cambrian separation.[10] Precordillera fauna records diverge from that in Laurentia after the Ordovician, and receive an increasing amount of fauna that also appears in Gondwana. This gets to the point that Precordillera is separated from Laurentia by sea-floor expansion, becoming independent continents and approaching Gondwana.[7]

Models of evolution

Regarding stratigraphical records and fossil evidence, multiple geological models has been published to explain the evolution of the Precordillera contributing to the Pre-Andean history of Gondwana.

Micro-continent model

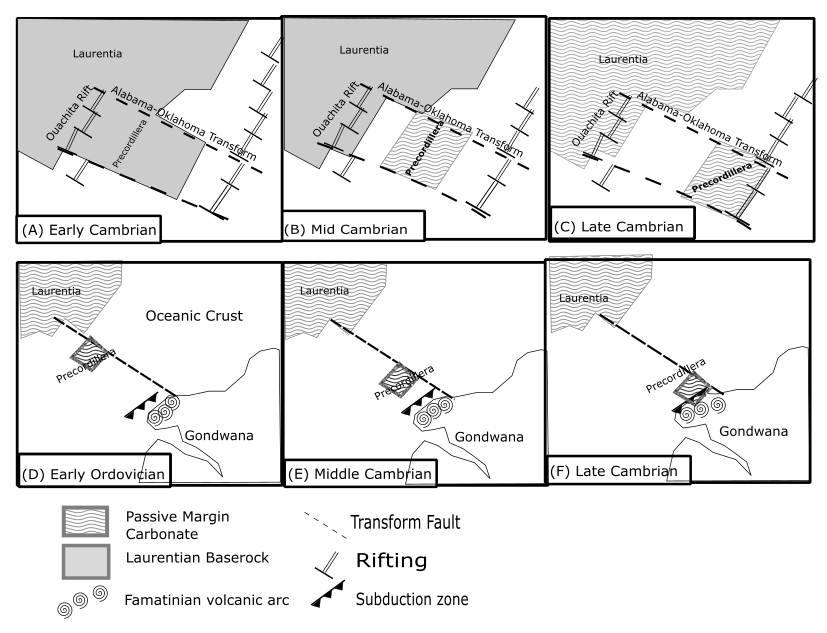

The micro-continent model was suggested by Thomas and Astini.[11] It says that Precordillera originates from Laurentia from the south-east of the Ouachita Embayment. It detached via the Ouachita Rift in Early Cambrian. After that Precordillera acts as an independent continent traveling through the Iapetus Ocean along the Alabama-Oklahoma transform fault. Finally the continent collided with the Gondwana continent in middle Ordovician, changing the environment from a passive margin to extensive rifting. This model is strongly supported by the thick carbonate complex as well as matching fauna records.[2]

Continental-collision model

The continent-collision model is an alternative model explaining the evolution of Precordillera.[2] Dalziel has reconstructed the Paleozoic plate development and proposed a narrow early Paleozoic Iapetus Ocean between Laurentia and Gondwana.[3] Dalziel named the model as the "Texas Plateau Hypothesis". Texas Plateau is the term describing the Precordillera at the time it was attached to its parental Laurentia, suggesting that Precordillera was always attached to Laurentia until a supercontinental collision between Laurentia and Gondwana shut down the Iapetus Ocean. After the collision, the continent rifted away during late Ordovician, so that Precordillera was no longer attached to Laurentia and stuck to the western Gondwana. This model is also known as "paired rift margin".[8]

Precordillera as not a part of Laurentia

Finney reconsidered the possibility of micro-continent model through U-Pb zircon dating and discovered that the dating result favours the Gondwana province instead of a drifting model from Laurentia.[4] He raised multiple ideas, such as reconsidering Western Sierras Pampeanas as autochthonous to Gondwana; the rocks between Precordillera and Famatina are instead a crustal fragment of Gondwana[4] that cannot be explained by the Laurentian drifting models. He proposed another model saying the Precordillera, or Cuyania was at the Southern margin of Gondwana and started drifting along the transform fault in mid-late Ordovician. Finally it reached the position where it was subducting beneath the Famatinan belt in Devonian.[7]

Post-collision period

After the collision of Precordillera with Gondwana, Precordillera is dominated by crustal extension. Multiple sets of horsts and grabens created sudden drowning and shallowing events. Elevated blocks were then eroded and the irregular fragments were collected and deposited at the wedges or grabens, forming conglomerate or breccia in the graben area.[7] The fauna records in Precordillera become consistent with Gondwana.[2] During Silurian to Devonian periods, increasing metamorphism or magmatic activities with structural deformation showed the approach of the Chilenia terrace from the west and Precordillera finally locked into the position with Gondwana.[2]

References

- ^ Ramos, V.A., Jordan, T.E., Allmendinger, R.W., Mpodozis, M.C., Kay, S.M., Cortes, J.M., Palma, M. (1986). Paleozoic terranes of the central Argentine-Chilean Andes. Tectonics, 5. pp. 5, 855–880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Benedetto, J. L. (1998). Early Palaeozoic Brachiopods and associated shelly faunas from western Gondwana: their bearing on the geodynamic history of the pre-Andean margin. The Proto-Andean Margin of Gondwana. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. London. pp. 57–83.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Dalziel, I. W. D. (1993). Tectonic tracers and the origin of the proto-Andean margin. XII Congreso Geologico Argentino u II Congreso de Exploracion deHidrocarburos, Mendoza, Actas, III. pp. 367–374.

- ^ a b c Finney, S. C. (2007). "The parautochthonous Gonwanan origin of the Cuyania (greater Precordillera) terrane of Argentina: A re-evaluation of evidence used to support an allochthonous Laurentian origin". Geologica Acta. 5: 127–158.

- ^ "precordillera". Diccionario de la lengua española - Edición del Tricentenario (in Spanish).

- ^ Jordan, T. E. (1983). "Andean segmentation related to geometry of subducted Nazca plate". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 94: 341–361. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1983)94<341:atrtgo>2.0.co;2.

- ^ a b c d e f Astini, R. A. (1998). Stratigraphical evidence supporting the rifting, drifting and collision of the Laurentian Precordillera terrane of western Argentina. The Proto-Andean Margin of Gondwana. Geological Society. London, Special Publication. pp. 11–33.

- ^ a b c d Bond, C. G., Nickson, A. & Kominz, M. A. (1984). Breakup of a supercontinent between 625 Ma and 555 Ma: new evidence and implications for continental histories. Earth Planet Science Letters, 80. pp. 29–42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Keller, M., Buggisch, W. & Lehnert, O. (1998). The stratigraphical record of the Argentine Precordillera and its plate-tectonic background. The Proto-Andean Margin of Gondwana. Geological Society, London, Special Publication, 142. pp. 35–56.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Astini, R.A. (1995). "Paleoclimates and paleogeographic paths of the Argentine Precordillera during the Ordovician: evidence from climatically sensitive lithofacies". Ordovician Odyssey. Book 77: 177–180.

- ^ Thomas, W. A.; Astini, R. A. (1996). The Argentine Precordllera: a traveler from the Ouachita embayment of North American Laurentia. Science, 273. pp. 752–757.