Genotoxicity

Genotoxicity is the property of chemical agents that damage the genetic information within a cell causing mutations, which may lead to cancer. While genotoxicity is often confused with mutagenicity, all mutagens are genotoxic, but some genotoxic substances are not mutagenic. The alteration can have direct or indirect effects on the DNA: the induction of mutations, mistimed event activation, and direct DNA damage leading to mutations. The permanent, heritable changes can affect either somatic cells of the organism or germ cells to be passed on to future generations.[1] Cells prevent expression of the genotoxic mutation by either DNA repair or apoptosis; however, the damage may not always be fixed leading to mutagenesis.

To assay for genotoxic molecules, researchers assay for DNA damage in cells exposed to the toxic substrates. This DNA damage can be in the form of single- and double-strand breaks, loss of excision repair, cross-linking, alkali-labile sites, point mutations, and structural and numerical chromosomal aberrations.[2] The compromised integrity of the genetic material has been known to cause cancer. As a consequence, many sophisticated techniques including Ames Assay, in vitro and in vivo Toxicology Tests, and Comet Assay have been developed to assess the chemicals' potential to cause DNA damage that may lead to cancer.

Mechanism

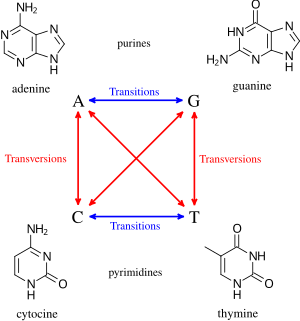

Genotoxic substances induce damage to the genetic material in the cells through interactions with the DNA sequence and structure. For example, the transition metal chromium interacts with DNA in its high-valent oxidation state, incurring DNA lesions which lead to carcinogenesis. The metastable oxidation state Cr(V) is achieved through reductive activation. Researchers performed an experiment to study the interaction between DNA with the carcinogenic chromium by using a Cr(V)-Salen complex at the specific oxidation state.[3] The interaction was specific to the guanine nucleotide in the genetic sequence. In order to narrow the interaction between the Cr(V)-Salen complex with the guanine base, the researchers modified the bases to 8-oxo-G so to have site specific oxidation. The reaction between the two molecules caused DNA lesions; the two lesions observed at the modified base site were guanidinohydantoin and spiroiminodihydantoin. To further analyze the site of lesion, it was observed that polymerase stopped at the site and adenine was inappropriately incorporated into the DNA sequence opposite of the 8-oxo-G base. Therefore, these lesions predominately contain G→T transversions. High-valent chromium is seen to act as a carcinogen as researchers found that "the mechanism of damage and base oxidation products for the interaction between high-valent chromium and DNA... are relevant to in vivo formation of DNA damage leading to cancer in chromate-exposed human populations".[3] Consequently, it shows how high-valent chromium can act as a carcinogen with 8-oxo-G forming xenobiotics.[3]

Another example of a genotoxic substance causing DNA damage are pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs). These substances are found mainly in plant species and are poisonous to animals, including humans; about half of them have been identified as genotoxic and many as tumorigenic. The researchers concluded from testing that when metabolically activated, "PAs produce DNA adducts, DNA cross-linking, DNA breaks, sister chromatid exchange, micronuclei, chromosomal aberrations, gene mutations, and chromosome mutations in vivo and in vitro."[4] The most common mutation within the genes are G:C → T:A tranversions and tandem base substitution. The pyrrolizidine alkaloids are mutagenic in vivo and in vitro and, therefore, responsible for the carcinogenesis prominently in the liver.[4] Comfrey is an example of a plant species that contains fourteen different PAs. The active metabolites interact with DNA to cause DNA damage, mutation induction, and cancer development in liver endothelial cells and hepatocytes. The researchers discovered in the end that the "comfrey is mutagenic in liver, and PA contained in comfrey appear to be responsible for comfrey-induced toxicity and tumor induction,".[5]

Test techniques

The purpose of genotoxicity testing is to determine if a substrate will influence genetic material or may cause cancer. They can be performed in bacterial, yeast, and mammalian cells.[2] With the knowledge from the tests, one can control early development of vulnerable organisms to genotoxic substances.[1]

Bacterial Reverse Mutation Assay

The Bacterial Reverse Mutation Assay, also known as the Ames Assay, is used in laboratories to test for gene mutation. The technique uses many different bacterial strains in order to compare the different changes in the genetic material. The result of the test detects the majority of genotoxic carcinogens and genetic changes; the types of mutations detected are frame shifts and base substitutions.[6]

in vitro toxicology testing

The purpose of in vitro testing is to determine whether a substrate, product, or environmental factor induces genetic damage. One technique entails cytogenetic assays using different mammalian cells.[6] The types of aberrations detected in cells affected by a genotoxic substance are chromatid and chromosome gaps, chromosome breaks, chromatid deletions, fragmentation, translocation, complex rearrangements, and many more. The clastogenic or aneugenic effects from the genotoxic damage will cause an increase in frequency of structural or numerical aberrations of the genetic material.[6] This is similar to the micronucleus test and chromosome aberration assay, which detect structural and numerical chromosomal aberrations in mammalian cells.[1]

In a specific mammalian tissue, one can perform a mouse lymphoma TK+/- assay to test for changes in the genetic material.[6] Gene mutations are commonly point mutations, altering only one base within the genetic sequence to alter the ensuing transcript and amino acid sequence; these point mutations include base substitutions, deletions, frame-shifts, and rearrangements. Also, chromosomes' integrity may be altered through chromosome loss and clastogenic lesions causing multiple gene and multilocus deletions. The specific type of damage is determined by the size of the colonies, distinguishing between genetic mutations (mutagens) and chromosomal aberrations (clastogens).[6]

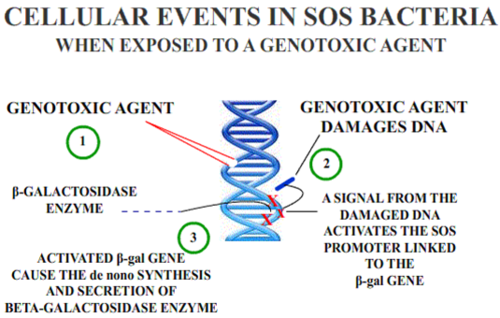

The SOS/umu assay test evaluates the ability of a substance to induce DNA damage; it is based on the alterations in the induction of the SOS response due to DNA damage. The benefits of this technique are that it is a fast and simple method and convenient for numerous substances. These techniques are performed on water and wastewater in the environment.[7]

in vivo testing

The purpose for in vivo testing is to determine the potential of DNA damage that can affect chromosomal structure or disturb the mitotic apparatus that changes chromosome number; the factors that could influence the genotoxicity are ADME and DNA repair. It can also detect genotoxic agents missed in in vitro tests. The positive result of induced chromosomal damage is an increase in frequency of micronucelated PCEs.[6] A micronucleus is a small structure separate from the nucleus containing nuclear DNA arisen from DNA fragments or whole chromosomes that were not incorporated in the daughter cell during mitosis. Causes for this structure are mitotic loss of acentric chromosomal fragments (clastogenicity), mechanical problems from chromosomal breakage and exchange, mitotic loss of chromosomes (aneugenicity), and apoptosis. The micronucleus test in vivo is similar to the in vitro one because it tests for structural and numerical chromosomal aberrations in mammalian cells, especially in rats' blood cells.[6]

Comet assay

Comet assays are one of the most common tests for genotoxicity. The technique involves lysing cells using detergents and salts. The DNA released from the lysed cell is electrophoresed in an agarose gel under neutral pH conditions. Cells containing DNA with an increased number of double-strand breaks will migrate more quickly to the anode. This technique is advantageous in that it detects low levels of DNA damage, requires only a very small number of cells, is cheaper than many techniques, is easy to execute, and quickly displays results. However, it does not identify the mechanism underlying the genotoxic effect or the exact chemical or chemical component causing the breaks.[8]

Cancer

Genotoxic effects such as deletions, breaks and/or rearrangements can lead to cancer if the damage does not immediately lead to cell death. Regions sensitive to breakage, called fragile sites, may result from genotoxic agents (such as pesticides). Some chemicals have the ability to induce fragile sites in regions of the chromosome where oncogenes are present, which could lead to carcinogenic effects. In keeping with this finding, occupational exposure to some mixtures of pesticides are positively correlated with increased genotoxic damage in the exposed individuals. DNA damage is not uniform in its severity across populations because Individuals vary in their ability to activate or detoxify genotoxic substances, which leads to variability in the incidence of cancer among individuals. The difference in ability to detoxify certain compounds is due to individuals' inherited polymorphisms of genes involved in the metabolism of the chemical. Differences may also be attributed to individual variation in efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms[9]

The metabolism of some chemicals results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is a possible mechanism of genotoxicity. This is seen in the metabolism of arsenic, which produces hydroxyl radicals, which are known to cause genotoxic effects.[10] Similarly, ROS have been implicated in genotoxicity caused by particles and fibers. Genotoxicity of nonfibrous and fibrous particles is characterized by high production of ROS from inflammatory cells.[11]

Genotoxins implicated in the four most common cancers worldwide

Major genotoxic agents responsible for the four most common cancers worldwide (lung, breast, colon and stomach) have been identified.

Lung cancer is the most frequent cancer in the world, both in terms of yearly cases (1.61 million cases; 12.7% of all cancer cases) and deaths (1.38 million deaths; 18.2% of all cancer deaths).[12] Tobacco smoke is the main cause of lung cancer. Risk estimates for lung cancer indicate that tobacco smoke is responsible for 90% of lung cancers in the United States. Tobacco smoke contains more than 5,300 identified chemicals. The most significant carcinogens in tobacco smoke have been determined by a "Margin of Exposure" approach.[13] By this approach, the tumorigenic compounds in tobacco smoke were, in order of importance, acrolein, formaldehyde, acrylonitrile, 1,3-butadiene, cadmium, acetaldehyde, ethylene oxide, and isoprene. In general, these compounds are genotoxic and cause DNA damage. As examples, DNA damaging effects have been reported for acrolein,[14] formaldehyde,[15] and acrylonitrile.[16]

Breast cancer is the second most frequent cancer worldwide on a yearly basis [(1.38 million cases, 10.9% of all cancer cases), and ranks 5th as cause of death (458,000, 6.1% of all cancer deaths)].[12] Breast cancer risk is associated with persistently high blood levels of estrogen.[17] Estrogen likely contributes to breast carcinogenesis by the following three processes; (1) metabolic conversion of estrogen to genotoxic, mutagenic carcinogens, (2) stimulation of growth of tissues, and (3) repression of phase II detoxification enzymes that metabolize genotoxic reactive oxygen species, thus resulting in increased oxidative DNA damage.[18][19][20] The principal human estrogen, estradiol, can be metabolized to quinone derivatives that form DNA adducts.[21] These derivatives can cause the removal of bases from the phosphodiester backbone of DNA (e.g. depurination). This removal may be followed by inaccurate repair or replication of the apurinic site leading to mutation and eventually cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the third most frequent cancer worldwide [1.23 million cases (9.7% of all cancer cases), 608,000 deaths (8.0% of all cancer deaths)].[12] In the United States, tobacco smoke may be responsible for up to 20% of colorectal cancers.[22] In addition, bile acids are implicated by substantial evidence as an important genotoxic factor in colon cancer.[23] In particular, the bile acid deoxycholic acid acid causes the production of DNA-damaging reactive oxygen species in human and rodent colon epithelial cells.[23]

Stomach cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide [990,000 cases (7.8% of all cancer cases), 738,000 deaths (9.7% of all cancer deaths )].[12] Infection by Helicobacter pylori is the main causative factor in stomach cancer. Chronic inflammation due to H. pylori, if untreated, is often long-standing. H. pylori infection of gastric epithelial cells causes increased production of genotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS).[24][25] ROS cause oxidative damage to DNA that includes the major base alteration 8-Oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine. In a recent retrospective study it was found that use of a bile acid sequestrant was associated with a significant reduction in gastric cancer risk, suggesting that bile acids may be a contributory factor in stomach cancer.[26]

Genotoxic chemotherapy

Genotoxic chemotherapy is the treatment of cancer with the use of one or more genotoxic drugs. The treatment is traditionally part of standardized regime. By utilizing the destructive properties of genotoxins treatments aims to induce DNA damage into cancer cells. Any damage done to a cancer is passed on to descendent cancer cells as proliferation continues. If this damage is severe enough, it will induce cells to undergo apoptosis.[27]

Risks

A drawback of treatment is that many genotoxic drugs are effective on cancerous cells and normal cells alike. Selectivity of a particular drug's action is based on the sensitivity of the cells themselves. So, while rapidly dividing cancer cells are particularly sensitive to many drug treatments, often normal functioning cells are affected.[27]

Another risk of treatment is that, in addition to being genotoxic, many of the drugs are also mutagenic and cytotoxic. So the effects of these drugs are not limited to just DNA damage. In addition, some of these drugs that are meant to treat cancers are also carcinogens themselves, raising the risk of secondary cancers, such as leukemia.[27]

Different treatments

This table depicts different genotoxic-based cancer treatments along with examples.[27]

| Treatment | Mechanism | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Alkylating agents | interfere with DNA replication and transcription by modifying DNA bases. | Busulfan, Carmustine, Mechlorethamine |

| Intercalating agents | interfere with DNA replication and transcription by wedging themselves into the spaces in between DNA's nucleotides | Daunorubicin, Doxorubicin, Epirubicin |

| Enzyme inhibitors | inhibit enzymes that are crucial to DNA replication | Decitabine, Etoposide, Irinotecan |

Kidney

Genotoxic DNA damage in the kidney has been implicated in both acute and chronic kidney injury, as well as in renal cell carcinoma.[28] Studies of humans with genetic deficiencies in DNA repair pathways have revealed that their kidneys are particularly vulnerable to DNA damages such as DNA crosslinks, DNA breaks and transcription-blocking damage.[28]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Kolle S (2012-06-01). "Genotoxicity and Carcinogenicity". BASF The Chemical Company. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ a b "Genotoxicity: Validated Non-animal Alternatives". AltTox.org. 2011-06-20. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ a b c Sugden KD, Campo CK, Martin BD (September 2001). "Direct oxidation of guanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine in DNA by a high-valent chromium complex: a possible mechanism for chromate genotoxicity". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 14 (9): 1315–22. doi:10.1021/tx010088+. PMID 11559048.

- ^ a b Chen T, Mei N, Fu PP (April 2010). "Genotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 30 (3): 183–96. doi:10.1002/jat.1504. PMC 6376482. PMID 20112250.

- ^ Mei N, Guo L, Fu PP, Fuscoe JC, Luan Y, Chen T (October 2010). "Metabolism, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of comfrey". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 13 (7–8): 509–26. Bibcode:2010JTEHB..13..509M. doi:10.1080/10937404.2010.509013. PMC 5894094. PMID 21170807.

- ^ a b c d e f g Furman G (2008-04-17). "Genotoxicity Testing for Pharmaceuticals Current and Emerging Practices" (PDF). Paracelsus, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ Končar H (2011). "In Vitro Genotoxicity Testing". National Institute of Biology. Archived from the original on 2013-03-07. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ Tice RR, Agurell E, Anderson D, Burlinson B, Hartmann A, Kobayashi H, et al. (2000). "Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing" (PDF). Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 35 (3): 206–21. Bibcode:2000EnvMM..35..206T. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(2000)35:3<206::AID-EM8>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID 10737956.

- ^ Bolognesi, Claudia (June 2003). "Genotoxicity of pesticides: A review of human biomonitoring studies". Mutation Research. 543 (3): 251–272. Bibcode:2003MRRMR.543..251B. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(03)00015-2. PMID 12787816.

- ^ Liu SX, Athar M, Lippai I, Waldren C, Hei TK (February 2001). "Induction of oxyradicals by arsenic: implication for mechanism of genotoxicity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (4): 1643–8. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.1643L. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1643. PMC 29310. PMID 11172004.

- ^ Schins RP (January 2002). "Mechanisms of genotoxicity of particles and fibers". Inhalation Toxicology. 14 (1): 57–78. Bibcode:2002InhTx..14...57S. doi:10.1080/089583701753338631. PMID 12122560. S2CID 24802577.

- ^ a b c d Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (December 2010). "Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008". Int J Cancer. 127 (12): 2893–2917. doi:10.1002/ijc.25516. PMID 21351269.

- ^ Cunningham FH, Fiebelkorn S, Johnson M, Meredith C (November 2011). "A novel application of the Margin of Exposure approach: segregation of tobacco smoke toxicants". Food Chem Toxicol. 49 (11): 2921–33. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.019. PMID 21802474.

- ^ Liu D, Cheng Y, Tang Z, Mei X, Cao X, Liu J (January 2022). "Toxicity mechanism of acrolein on DNA damage and apoptosis in BEAS-2B cells: Insights from cell biology and molecular docking analyses". Toxicology. 466: 153083. Bibcode:2022Toxgy.46653083L. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2021.153083. PMID 34958888.

- ^ Mulderrig L, Garaycoechea JI, Tuong ZK, Millington CL, Dingler FA, Ferdinand JR, Gaul L, Tadross JA, Arends MJ, O'Rahilly S, Crossan GP, Clatworthy MR, Patel KJ (December 2021). "Aldehyde-driven transcriptional stress triggers an anorexic DNA damage response". Nature. 600 (7887): 158–163. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..158M. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04133-7. PMID 34819667.

- ^ Pu X, Kamendulis LM, Klaunig JE (September 2009). "Acrylonitrile-induced oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage in male Sprague-Dawley rats". Toxicol Sci. 111 (1): 64–71. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp133. PMC 2726299. PMID 19546159.

- ^ Yager JD, Davidson NE (January 2006). "Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer". N Engl J Med. 354 (3): 270–82. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050776. PMID 16421368.

- ^ Ansell PJ, Espinosa-Nicholas C, Curran EM, Judy BM, Philips BJ, Hannink M, Lubahn DB (January 2004). "In vitro and in vivo regulation of antioxidant response element-dependent gene expression by estrogens". Endocrinology. 145 (1): 311–7. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0817. PMID 14551226.

- ^ Belous AR, Hachey DL, Dawling S, Roodi N, Parl FF (January 2007). "Cytochrome P450 1B1-mediated estrogen metabolism results in estrogen-deoxyribonucleoside adduct formation". Cancer Res. 67 (2): 812–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2133. PMID 17234793.

- ^ Bolton JL, Thatcher GR (January 2008). "Potential mechanisms of estrogen quinone carcinogenesis". Chem Res Toxicol. 21 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1021/tx700191p. PMC 2556295. PMID 18052105.

- ^ Yue W, Santen RJ, Wang JP, Li Y, Verderame MF, Bocchinfuso WP, Korach KS, Devanesan P, Todorovic R, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL (September 2003). "Genotoxic metabolites of estradiol in breast: potential mechanism of estradiol induced carcinogenesis". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 86 (3–5): 477–86. doi:10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00377-7. PMID 14623547.

- ^ Giovannucci E, Martínez ME (December 1996). "Tobacco, colorectal cancer, and adenomas: a review of the evidence". J Natl Cancer Inst. 88 (23): 1717–30. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.23.1717. PMID 8944002.

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Bernstein C (January 2023). "Bile acids as carcinogens in the colon and at other sites in the gastrointestinal system". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 248 (1): 79–89. doi:10.1177/15353702221131858. PMC 9989147. PMID 36408538.

- ^ Ding SZ, Minohara Y, Fan XJ, Wang J, Reyes VE, Patel J, Dirden-Kramer B, Boldogh I, Ernst PB, Crowe SE (August 2007). "Helicobacter pylori infection induces oxidative stress and programmed cell death in human gastric epithelial cells". Infect Immun. 75 (8): 4030–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.00172-07. PMC 1952011. PMID 17562777.

- ^ Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T (2011). "Redox biology and gastric carcinogenesis: the role of Helicobacter pylori". Redox Rep. 16 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1179/174329211X12968219310756. PMC 6837368. PMID 21605492.

- ^ Noto JM, Piazuelo MB, Shah SC, Romero-Gallo J, Hart JL, Di C, Carmichael JD, Delgado AG, Halvorson AE, Greevy RA, Wroblewski LE, Sharma A, Newton AB, Allaman MM, Wilson KT, Washington MK, Calcutt MW, Schey KL, Cummings BP, Flynn CR, Zackular JP, Peek RM (May 2022). "Iron deficiency linked to altered bile acid metabolism promotes Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation-driven gastric carcinogenesis". J Clin Invest. 132 (10). doi:10.1172/JCI147822. PMC 9106351. PMID 35316215.

- ^ a b c d Walsh D (2011-11-18). "Genotoxic Drugs". Cancerquest.org. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ a b Garaycoechea JI, Quinlan C, Luijsterburg MS (April 2023). "Pathological consequences of DNA damage in the kidney". Nat Rev Nephrol. 19 (4): 229–243. doi:10.1038/s41581-022-00671-z. PMID 36702905.

Further reading

- Jha AN, Cheung VV, Foulkes ME, Hill SJ, Depledge MH (January 2000). "Detection of genotoxins in the marine environment: adoption and evaluation of an integrated approach using the embryo-larval stages of the marine mussel, Mytilus edulis". Mutation Research. 464 (2): 213–28. Bibcode:2000MRGTE.464..213J. doi:10.1016/s1383-5718(99)00188-6. PMID 10648908.

- Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (2011). Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Metal ions in toxicology: effects, interactions, interdependencies. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 8. pp. vii–viii. doi:10.1039/9781849732512. ISBN 978-1-84973-094-5. PMID 21473373.

- Bal W, Protas AM, Kasprzak KS (2011). "13. Genotoxicity of metal ions: chemical insights". In Sigel R, Sigel, Sigel H (eds.). Metal Ions in Toxicology: Effects, Interactions, Interdependencies (Metal Ions in Life Sciences). Vol. 8. Cambridge, Eng: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 319–373. doi:10.1039/9781849732116-00319. ISBN 978-1-84973-091-4.

- Smith MT (December 1996). "The mechanism of benzene-induced leukemia: a hypothesis and speculations on the causes of leukemia". Environmental Health Perspectives. 104 (Suppl 6): 1219–25. doi:10.1289/ehp.961041219. PMC 1469721. PMID 9118896.