Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri

Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (1651–1725) was an Italian adventurer and traveler. He was among the first Europeans to tour the world by securing passage on ships involved in the carrying trade; his travels, undertaken for pleasure rather than profit saw him travel through the Middle East, India, China and the New World within a span of five years. Some suspected him of spying for the Vatican (or rather for the Jesuits) on his journey. The reliability of his travels were once doubted, but is now considered to be authentic due to the details observed in his writings.

Biography

Gemelli Careri was born in Taurianova, 1651, and died in Naples, 1725. He obtained a doctorate in law at the College of Jesuits in Naples. After completing his studies he briefly entered the judiciary. In 1685 he took time off to travel around Europe (France, Spain, Germany, and Hungary). In Hungary he was wounded during the siege of Buda.

In 1687 he returned to Naples and re-entered the judiciary. He also began work on his first two books: "Relazione delle Campagne d'Ungheria" (1689) with co-author Matteo Egizio, and "Viaggi in Europa" (1693). At this time Gemelli encountered frustrations with his legal profession. He was denied certain opportunities because he did not have an established aristocratic origin. Eventually, he decided to suspend his career for a round-the-world trip across the globe. This five-year trip would lead to his best known six-volume book, Giro Del Mondo (1699).[1]

World voyage

Gemelli Careri realized that he could finance his trip by carefully purchasing goods at each stage that would have enhanced value at the next stage: at Bandar-Abbas on the Persian Gulf, he asserts, the traveler should pick up "dates, wine, spirits, and all the fruits of Persia, which one carries to India either dried or pickled in vinegar, on which one makes a good profit".[2]

Gemelli Careri started his world trip in 1693, with a visit to Egypt, Constantinople, and the Holy Land. At the time, this Middle Eastern route was already becoming a standard route for an excursion into foreign lands, a journey so normalized that it was almost not worth writing home about. However, from there he took the less traveled routes. After crossing Armenia and Persia, he visited Southern India and entered China, where the Jesuit missionaries assumed that such an unusual Italian visitor could be a spy working for the pope. This fortuitous misunderstanding opened for Gemelli many of the most tightly closed doors of the country. He visited the emperor at Beijing, attended the Lantern Festival celebrations and toured the Great Wall.

"Most of the structure, as has been said, is of brick, so well built that it does not only last but looks new after several ages. It is above 1800 years since the Emperor Xi-hoam-ti caused it to be built against the incursions of the Tartars. This was one of the greatest, and most extravagant works that ever was undertaken. In prudence the Chinese should have secured the most dangerous passes: But what I thought most ridiculous was to see the wall run up to the top of a vast high and steep mountain, where the Birds would hardly build much less the Tartar horses climb... And if they conceited those people could make their way climbing the clefts and rocks it was certainly a great folly to believe their Rage could be stopped by so low a wall."[3]

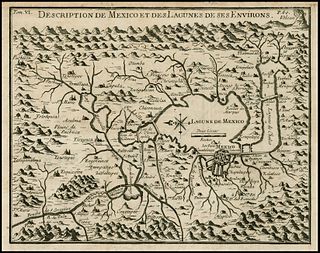

From Macau, Gemelli Careri sailed to the Philippines, where he stayed two months while waiting for the departure of a Manila galleon, for which he carried quicksilver, for a 300% profit in Mexico. In the meantime, as Gemelli described it in his journal, the half-year-long transoceanic trip to Acapulco was a nightmare plagued with bad food, epidemic outbursts, and the occasional storm. In Mexico, he became friends with the Mexican creole patriot and savant Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who took the Italian traveler to the great ruins of Teotihuacan. Sigüenza spoke with Gemelli about his theories of the ancient Mexicans and entrusted him with information about the Mexican calendar, which had appeared in Gemelli's account.[4] As well as having visited the pyramids at Teotihuacan, he also visited several mining towns. After leaving Mexico city he visited the city of Puebla de Los Angeles and several towns as he traveled to the port city of Veracruz, where he joined a Spanish fleet headed toward Cuba. Gemelli finally returned to Europe after five years of travel when he joined the Spanish treasure fleet in Cuba.[5]

Publications

- Relazione delle Campagne d'Ungheria (1689)

- Viaggi in Europa (1693)[6]

- Giro Del Mondo (1699)

- Part 1 (Turkey and Middle East)[7]

- Part 2 (Persia)[8]

- Part 3 (Hindustan)[9]

- Part 4 (China)[10]

- Part 5 (Philippines)[11]

- Part 6 (New Spain)[12]

- Voyage Round the World (1704, London: English Translation - a.k.a. John Francis Gemelli Careri)

- Voyage du Tour du Monde (1719, Paris: French Translation - a.k.a. Jean Francois Gemelli Careri)

Literary significance and criticism

The aim of Giro Del Mondo - a faithful description of the countries visited - was emphasized by Giosef-Antonio Guerrieri in his preface. While pointing out the difference between the account of a journey and "an imaginary journey", Guerrieri praised Gemelli Careri for the reliability of his experiences, and criticized those who were prone to fantasize over geographic maps.

For many years scholars and experts did not consider Gemelli Careri's adventurous journey authentic. Later, it was ascertained that he collected important historical documents in order to identify correctly those exotic realities in greater detail. The sixth volume of Giro Del Mondo, which covers only Mexico, contains information gathered from codices that existed prior to the Conquest, which he received access to via Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora; it also contains several illustrations of Aztec warriors gathered from these codices. In New Spain, Gemelli Careri had the opportunity to study the Mesoamerican pyramids carefully (their affinity to the Egyptian pyramids led him to believe that the ancient Egyptians and the Amerindians both descended from the inhabitants of Atlantis), which Sigüenza had long held.[13][14] Due to lack of funds, Sigüenza himself had been unable to publish much on the ancient Mexicans, but through Gemelli's work was able to disseminate his ideas and even drawings from the ancient Mexican manuscripts.[15]

An 1849 release of The Calcutta Review (a periodical now published by the University of Calcutta), stated the following about Gemelli's writings concerning India: "In a previous number of this Review we made an attempt to describe something of the Court and Camp of the best and wisest prince Muhainmedan India had ever beheld (Aurungzebe, Mogul emperor of Hindustan)... To this we are urged by two main considerations, the character of the age, and the materials at our command.... Sir H. M. Elliot's work has... met with, to a certain extent, adverse criticism, and some doubts have been raised as to the soundness, or the justice, of its conclusions. It is therefore (possible that readers may be willing) to peruse a description of the Government of Aurungzebe, taken not from native historians, but from the accounts of men who saw with the eyes of travelers.

"From three men, who all visited India during the reign of Aurungzebe, the most valuable and the most curious information is attainable... The second of the triumvirate, on whom we mainly rely, is the Doctor John Francis Gemelli Careri. Natural curiosity and domestic misfortunes were, he tells us, his motives for traveling. Of the three (sources this paper is based), he is the most discursive in his narration, the most piquant in his anecdotes, the most amusing in his simplicity. As he traveled for no one particular aim, but to see and to hear, there are few Indian topics, on which he does not give us something. Natural productions, the beasts and the birds, manners, Hindu theology, state maxims, the causes of Portuguese supremacy and degradation, anecdotes of the camp, the convent, and the Harem, accidents by water and land, complaints of personal inconvenience, and remarks on the tendency of Eastern despotism, are scattered plentifully throughout a narrative, which owes very much to the author's own liveliness and observation, but occasionally something, we are compelled to say, to the labours of others who had gone before. His plagiarism is, however, confined to specifications of caste or creed. Where he saw or suffered personally, his narrative is clear, picturesque, and beyond suspicion."[16]

Italian Capuchin friar Ilarione da Bergamo had read Gemelli's account of New Spain when he wrote his travel narrative in the late eighteenth century. He refrained from going into detail in some descriptions because Gemelli had already given a full account.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Source Article: Giovanni_Francesco_Gemelli_Careri; Angela Amuso Maccarrone, Gianfrancesco Gemelli-Careri. L'Ulisse del XVII secolo, 2000

- ^ Quoted in Fernand Braudel. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilisation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century 1979 p. 169.

- ^ "Voyage Round the World", 1704, London: Vol. 4, p. 323-324

- ^ D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867, New York: Cambridge University Press 1991, 363, 366-67.

- ^ Source Article: Denis, Adrian L. "Early Cities of the Americas, Treasure City: Havana", University of California, 2003

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1708). Viaggi in Europa, Parte Prima, divisata in varie lettere familiari scritte al Signore Consiglieri Amato Dani (2nd ed.). Naples: Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1699). Giro del Mondo, Parte Prima, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute della Turchia. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli, Naples; Googlebooks.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1709). Giro del Mondo, Parte Seconda, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute della Persia. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli, Presso Francesco Antonio Perazzo, Naples.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1709). Giro del Mondo, Parte Terza, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute nell' Indostan. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli (1708), Presso Francesco Antonio Perazzo, Naples.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1709). Giro del Mondo, Parte Quarta, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute nella Cina. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli (1708), Presso Francesco Antonio Perazzo, Naples.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1709). Giro del Mondo, Parte Quinta, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute nell' Isole Fillipine. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli (1708), Presso Francesco Antonio Perazzo, Naples.

- ^ *Careri, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli (1709). Giro del Mondo, Parte Sesta, contenente le cose più raguardevoli vedute nella Nuova Spagna. Stamperia di Giuseppe Roselli (1708), Presso Francesco Antonio Perazzo, Naples.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867, New York: Cambridge University Press 1991 p. 365.

- ^ Quoted by Stefania Buccini: The Americas in Italian literature and culture, 1700-1825 Penn State Press, 1997 p.19

- ^ Irving A. Leonard, Baroque Times in Old Mexico: Seventeenth-Century Persons, Places, and Practices, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press 1959, pp. 201-02.

- ^ Quoted by: The Calcutta Review Volumes 11-12, University of Calcutta, 1849, p.303

- ^ Daily Life in Colonial Mexico: The Journey of Friar Ilarione da Bergamo, 1761-1768. Ed. Robert Ryal Miller and William J. Orr. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2000, pp. 32, 85, 92, 132, 156, 163

External links

- www.common-place.org

- Baroque Cycle related website

- "Giro Del Mondo" (Italian Version)

- English translation from 1704 (also at the Internet Archive)

- "Voyage du Tour du Monde": French translations of the first and fifth parts

- "The Americas in Italian Literature and Culture, 1700-1825"

- "The Calcutta Review" Volumes 11-12, 1849