French submarine Sfax

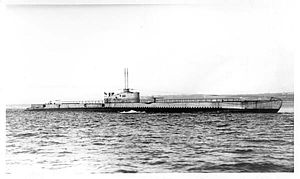

Sfax′s sister ship Ajax in 1930. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sfax |

| Namesake | Sfax, a city in Tunisia |

| Operator | French Navy |

| Ordered | 1930 |

| Builder | Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, Saint-Nazaire, France |

| Laid down | 28 July 1931 |

| Launched | 6 December 1934 |

| Commissioned | 7 September 1936 |

| Homeport | Brest, France |

| Fate | Sunk 19 December 1940 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Redoutable-class submarine |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 8.20 m (26 ft 11 in) |

| Draught | 4.70 m (15 ft 5 in) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | |

| Range |

|

| Complement | 61 |

| Armament |

|

Sfax was a French Navy Redoutable-class submarine of the M6 series commissioned in 1936. She participated in World War II, first on the side of the Allies from 1939 to June 1940 and then in the navy of Vichy France until a German submarine mistook her for an Allied submarine and sank her in December 1940.

Characteristics

Sfax was part of a fairly homogeneous series of 31 deep-sea patrol submarines also called "1,500-tonners" because of their displacement. All entered service between 1931 and 1939.

The Redoutable-class submarines were 92.3 metres (302 ft 10 in) long and 8.1 metres (26 ft 7 in) in beam and had a draft of 4.4 metres (14 ft 5 in). They could dive to a depth of 80 metres (262 ft). They displaced 1,572 tonnes (1,547 long tons) on the surface and 2,082 tonnes (2,049 long tons) underwater. Propelled on the surface by two diesel engines producing a combined 6,000 horsepower (4,474 kW), they had a maximum speed of 18.6 knots (34.4 km/h; 21.4 mph). When submerged, their two electric motors produced a combined 2,250 horsepower (1,678 kW) and allowed them to reach 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Also called “deep-cruising submarines”, their range on the surface was 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Underwater, they could travel 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) at 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph).

Sfax, Casabianca, and Le Glorieux were the only Redoutable-class submarines equipped with a radio direction finder.[2]

Construction and commissioning

Laid down at Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire in Saint-Nazaire, France, on 28 July 1931[3] with the hull number Q182, Sfax was launched on 6 December 1934.[3] She was commissioned on 7 September 1936.[3][4]

Service history

1936–1939

In 1937, all French submarines had their folding radio masts removed and replaced by a hoisting periscopic antenna.[5] Sfax also became one of only three submarines — along with her sister ships Casabianca and Le Glorieux — to receive a radio direction finder.[5] On 31 July 1938, a member of Sfax′s crew died in a road accident.[6]

By the beginning of 1939, Sfax was assigned to the 2nd Submarine Division based at Brest, France.[7] Her sister ships Achille, Casabianca, and Pasteur made up the rest of the division.[8] She underwent a refit at Brest from February to April 1939,[7] then patrolled in the Atlantic Ocean until later in 1939, when the 2nd Submarine Division was transferred to Toulon, France, for operations in the Mediterranean Sea.[7]

World War II

French Navy

When World War II began on 1 September 1939, Sfax — along with Achille, Casabianca, and Pasteur — was still assigned to the 2nd Submarine Division in the 4th Submarine Squadron in the 1st Flotilla, a component of the Forces de haute mer (High Seas Force), based at Brest.[5][6][9] On either 3 September 1939,[6][10] the day France declared war, or on 14 September 1939,[5] according to different sources, Sfax got underway to patrol off Vigo on the northern coast of Spain, where part of the German merchant fleet — which the Allies suspected of serving as supply ships for German U-boats — had taken refuge at the start of the war.[6][10] Sfax and the other submarines of her division, as well as their sister ships Agosta and Ouessant, spent several weeks patrolling off Vigo waiting in vain for German blockade runners until the patrols were discontinued at the end of October 1939.[5][7]

All four submarines of the 2nd Submarine Division subsequently were assigned to escort duty for Allied convoys in the Atlantic.[6][7][11] They departed Brest on 14 November 1939 and proceeded to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.[5] Despite encountering bad weather during their voyage, they arrived at Halifax at 07:30 on 25 November 1939.[5] The British Royal Navy submarines HMS Cachalot, HMS Narwhal, HMS Porpoise, and HMS Seal joined them there for escort duty on 26 November 1939.[5] On 2 December 1939, Convoy HX 11 — consisting of 11 British tankers, 33 British cargo ships, and a French cargo ship — departed Halifax bound for the United Kingdom with an escort consisting of Sfax, Casabianca, the British Royal Navy battleship HMS Revenge, and a number of Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy destroyers,[3] Sfax and Casabianca joining the escort on 4 December 1939.[5] On 17 December 1939, Sfax and Casabianca parted company with the convoy, which arrived safely in British waters on 18 December 1940,[3] and the two French submarines arrived at Brest the same day.[5] The 2nd Submarine Division continued convoy escort duty through the winter of 1939–1940.[7][11]

During the spring of 1940, Sfax and the other submarines of her division supported Allied forces fighting in the Norwegian campaign, but sources disagree on details of her service. One source claims that the division was based at Harwich in England on 22 March 1940, then moved on 17 April 1940 to Dundee, Scotland, to join the British submarines HMS Clyde and HMS Severn in forming the 9th Flotilla.[12] Another claims that Sfax did not depart Brest until 15 April 1940 and arrived at Harwich on 18 April 1940.[5] Yet another claims that Sfax arrived at Narvik, Norway, on 17 April 1940 and did not reach Dundee until the conclusion of her first war patrol of the Norwegian campaign.[7] Early in that patrol, which lasted two weeks,[7] she was almost torpedoed by Achille, which initially mistook her for a German U-boat.[13] During the patrol, Sfax fired two torpedoes at a German ship — described by one source as an "ocean liner"[5] but possibly the 2,863-gross register ton merchant ship Palime[3] — in the North Sea west-northwest of Egersund, Norway, at 58°30′N 005°30′E / 58.500°N 5.500°E at 07:25 on 22 April 1940.[3] Both torpedoes missed.[3] From 7 to 20 May 1940, she conducted a patrol with Achille and Casabianca off Bergen, Egersund, and Stavanger, Norway, but the French submarines found few targets.[5] Sfax′s commanding officer, Lieutenant de vaisseau (Ship-of-the-Line Lieutenant) L. V. Groix, later received a commendation for Sfax′s performance off Norway.[14]

German ground forces advanced into France on 10 May 1940, beginning the Battle of France. Sfax departed Dundee on 4 June 1940 and returned to Brest.[7] Italy declared war on France on 10 June 1940 and joined the invasion. As French defenses crumbled and German forces approached Brest, the French Navy ordered all vessels at Brest to evacuate the port, and directed that any vessels there unable to get underway were to be scuttled to prevent their capture by the Germans.[5] Sfax accordingly departed Brest on 19 June 1940 and proceeded to Casablanca in French Morocco.[7] She was at Casablanca[6] and still part of the 2nd Submarine Division[5] when the Battle of France ended in France's defeat and armistices with Germany on 22 June 1940 and with Italy on 24 June, both of which went into effect on 25 June 1940.

Vichy France

After France's surrender, Sfax served in the naval forces of Vichy France, based at Casablanca.[7] In the aftermath of the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir — in which a Royal Navy squadron attacked the French naval squadron at the base at Mers El Kébir near Oran on the coast of Algeria on 3 July 1940 — Sfax, Casabianca, and their sister ship Poncelet maintained a constant patrol in the Atlantic Ocean 20 nautical miles (37 km; 23 mi) off Casablanca from 6 to 18 July 1940 to protect the incomplete battleship Jean Bart, which had fled to Casablanca before the armistice.[5][7][15] On 23 or 28 October 1940, according to different sources, Sfax joined Casabianca and their sister ships Bévéziers and Sidi Ferruch in forming a new 2nd Submarine Division based at Casablanca.[5][16]

At 12:00 on 17 December 1940, the 2,785-ton French Navy fleet oiler Rhône got underway from Casablanca bound for Dakar, Senegal, carrying a cargo of munitions and 3,500 tons of fuel oil.[3][17][18] Ordered to transfer to Dakar to relieve the submarine Bévéziers there, Sfax belatedly received additional orders to escort Rhône on her voyage, and she also departed Casablanca that day.[7] Sfax caught up with Rhône at 16:00 on 17 December 1940, and the two vessels continued their voyage in company.[7]

Loss

Sfax′s and Rhône′s voyage southward along the African coast was uneventful until they reached a point between Cape Juby on the coast of Spanish Morocco and Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands on the afternoon of 19 December 1940.[7] At 16:40, Sfax — stationed about 400 metres (440 yd) off Rhône's starboard quarter, with both vessels making about 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) — was torpedoed by the German submarine U-37, which mistook Sfax and Rhône for Allied vessels.[3][17][18][19][20] Rhône′s crew observed a huge cloud of smoke rising from Sfax′s stern, followed by a gush of diesel oil and two violent explosions.[21] Within 30 seconds, Sfax sank by the stern at an angle of 40 degrees[21] in 80 metres (262 ft)[5] of water in the Atlantic Ocean either 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) off Cape Juby at 28°03′N 012°54′W / 28.050°N 12.900°W,[3][17][18][21][22] 60 nautical miles (110 km; 69 mi) off Cape Juby,[5] or 80 nautical miles (150 km; 92 mi) northeast of Cape Juby at 28°30′N 011°40′W / 28.500°N 11.667°W,[3][18] according to different sources.

With no reason to believe that the French vessels were under submarine attack, Rhône′s commanding officer concluded that Sfax had fallen victim to an internal explosion caused by the accidental detonation of torpedoes in her after torpedo room which had in turn caused an explosion of her after fuel tanks.[23] He ordered Rhône′s engines stopped and launched two whaleboats, which within 30 minutes rescued four survivors from Sfax and recovered the badly wounded and unresponsive Groix, who died without regaining consciousness.[24] Before the men aboard the whaleboats could board Rhône, U-37 torpedoed her at 17:20 forward of her bridge in hold number 4.[24] The hold was full of diesel oil, which caught fire.[24] Firefighting efforts failed, and when the spreading fire threatened to reach the 160 100-millimetre (3.9 in) shells in Rhône′s forward magazine, her crew and Sfax′s survivors abandoned ship in the two whaleboats and a rowboat.[24] It is unknown how Sfax′s four survivors were distributed among the boats.[25] The boats were overloaded, so Rhône's commanding officer and nine volunteers from her crew reboarded Rhône and an hour later, after darkness fell, managed to free and launch her motorboat, once again abandoning Rhône.[24]

At 20:00 on 19 December 1940, a Spanish fishing trawler found the motorboat, rescued Rhône's commanding officer and the nine volunteers from it, and took the motorboat in tow.[24] At 23:00, the trawler transferred the 10 survivors to the French cargo ship Fort Royal, which transmitted a signal reporting the events to the Vichy French naval command in Casablanca.[24] Although the signal failed to reach Casablanca, the French cargo ship Francois L-D received it and altered course to proceed to the scene of the attack.[24] Francois L-D took the 10 survivors aboard from Fort Royal and launched a motor whaleboat to conduct a fruitless search to the southeast for more survivors.[24] Francois L-D herself headed southwest, and at 07:45 on 20 December 1940 sighted one of Rhône′s whaleboats 10 nautical miles (19 km; 12 mi) from Rhône, rescuing six more men.[24] Rhône finally sank at 15:00 on 20 December 1940[24] at 28°03′N 012°54′W / 28.050°N 12.900°W.[17]

Francois L-D continued to search the area but found no more survivors, and she suspended her search at 18:30 on 20 December 1940 and headed for Agadir, French Morocco.[24] Air and other surface searches also met with no success.[24] However, Rhône's rowboat and second whaleboat made landfall in Spanish Morocco, the rowboat at 17:00 on 20 December near Hassi Chbiki and the second whaleboat not far to the north near Chbiki at 12:00 on 21 December 1940.[24] The men from the rowboat began an overland march toward Ifni, and survivors from the two boats — a total of 43 men — were reunited when the two groups encountered each other during this march.[24] A Spanish Army truck picked them up and took them to Xenel Marsa, where a medical officer put ashore by the Vichy French destroyer Brestois treated them for their wounds.[24] Heavy surf made it impossible to embark the survivors on Brestois, so the survivors were taken overland to the Spanish military outpost at Tan-Tan in Spanish Morocco, and from there either were flown to Cape Juby or carried by truck to Guelmin in French Morocco.[24]

Sixty-five of the 69 men aboard Sfax died in her sinking.[14][3][18] Eleven members of Rhône′s crew lost their lives.[17][14]

On 21 December 1940, U-37′s commanding officer, Kapitänleutnant (Captain Lieutenant) Nicolai Clausen, transmitted a report of the incident claiming that he had sighted a 7,329-gross register ton "Kopbard-type" tanker — apparently a reference to the French merchant tanker Kobard — and fired a torpedo at it, that the torpedo had gone off course due to a gyroscope failure and hit an "Amphtrite"-type submarine in the tanker′s convoy, and that the tanker subsequently had "burnt out," without explaining what made the tanker burn.[21] To avoid diplomatic embarrassment over a German submarine sinking ships of the navy of Vichy France, a pro-Axis neutral country, the Germans subsequently attempted to cover up U-37′s sinking of Sfax and Rhône. When the German High Command became aware of their identity, it issued a directive that "We shall continue to maintain to the outside world that there is no question of a German or Italian submarine in the sea area in question being responsible for the sinkings."[24] Clausen was sworn to secrecy[14] and I-37′s war diary (German: Kriegstagebuch) was purged of any reference to the sinkings; its entry for 19 December 1940 devoted itself to a discussion of confusion over signals arising from mistakes in the use of her Enigma machine,[21] otherwise stating merely "Nothing to see,"[18] and making a clumsy attempt to obfuscate U-37′s location by reporting that between 00:00 and 04:00 on 19 December 1940 she changed her position by a physically impossible 600 nautical miles (1,100 km; 690 mi) — some ten times farther than a U-boat could have moved in four hours — and placing her at the time of the sinkings in a grid sector located 350 miles (560 km) inland in the Sahara Desert in Algeria.[18][26]

Commemoration

Groix received a posthumous promotion to capitaine de corvette (corvette captain) "on exceptional grounds and for feats of war."[14] A street in Brest, his home town, is named for him.[14]

References

Citations

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau 1980, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Huan, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Allied Warships: FR Sfax, uboat.net Accessed 9 July 2022

- ^ Le Conte.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s u-boote.fr SFAX (in French) Accessed 14 August 2022

- ^ a b c d e f Sous-Marins Français Disparus & Accidents: Sous-Marin Sfax (in French) Accessed 14 August 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Morgan & Taylor, p. 78.

- ^ Huan, p. 49.

- ^ u-boote.fr PASTEUR (in French) Accessed 4 September 2022

- ^ a b Huan, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Huan, p. 67.

- ^ ACHILLE (in French) Accessed 5 August 2022

- ^ Picard, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f Morgan & Taylor, p. 81.

- ^ Huan, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Huan, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Ships hit by U-boats: Rhône, French Fleet oiler, uboat.net Accessed 9 July 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g Ships hit by U-boats: Sfax (Q 182) French Submarine, uboat.net Accessed 9 July 2022

- ^ Morgan & Taylor, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Huan, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e Morgan & Taylor, p. 79.

- ^ Huan, p. 98.

- ^ Morgan & Taylor, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Morgan & Taylor, p. 80.

- ^ Morgan & Taylor, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Morgan & Taylor, pp. 79, 80.

Bibliography

- Boulaire, Alain (2011). La Marine française: De la Royale de Richelieu aux missions d'aujourd'hui (in French). Quimper, France: éditions Palantines. p. 383. ISBN 978-2-35678-056-0.

- Fontenoy, Paul E. (2007). Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact (Weapons and Warfare). Santa Barbara, California. ISBN 978-1-85367-623-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[verification needed] - Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Huan, Claude (2004). Les Sous-marins français 1918–1945 (in French). Rennes: Marines Éditions. ISBN 9782915379075.

- Le Conte, Pierre (1936). Sous-marin "Sfax" (Saint-Nazaire) Date d'édition 1936 (in French). Saint-Nazaire: Ateliers et chantier de la Loire.

- Monaque, Rémi (2016). Une histoire de la marine de guerre française (in French). Paris: éditions Perrin. p. 526. ISBN 978-2-262-03715-4.

- Morgan, Daniel; Taylor, Bruce (2011). U-Boat Attack Logs: A Complete Record of Warship Sinkings From Original Sources 1939–1945. Barnsley, England: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-118-2.

- Picard, Claude (2006). Les Sous-marins de 1 500 tonnes (in French). Rennes: Marines Éditions. ISBN 2-915379-55-6.

- Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours, Volume II, 1870–2006 (PDF) (in French). Millau, France: Rezotel-Maury. p. 591. ISBN 2-9525917-1-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (2002). Dictionnaire d'Histoire maritime (in French). Paris: éditions Robert Laffont. pp. 1, 508. ISBN 2-221-08751-8.