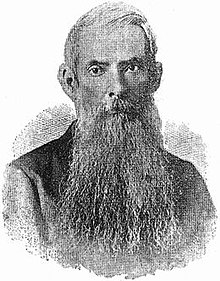

Francisco Vicente Aguilera

Francisco Vicente Aguilera was a Cuban patriot born in Bayamo, Cuba on June 23, 1821.[1] He had ten children with his wife Ana Manuela Maria Dolores Sebastiana Kindelan y Sanchez. He studied at the University of Havana receiving the degree of Bachelor of Laws.[2]

Aguilera had inherited a fortune from his father, and in 1867 he was the richest landowner in the eastern region of Cuba, owning extensive properties, sugar refineries, livestock, and slaves. He never bought any of the slaves that were regularly brought from the African coast and offered for sale. He only used the slaves he had inherited from his father. This required him to hire many free workers to plant and harvest the sugarcane and work the farms. He was mayor of Bayamo, and he was a freemason and the head of the Masonic lodge in Bayamo.[citation needed][3]

He traveled to many countries, including the U.S., France, England, and Italy. On his travels he came into contact with governments that had chiefs of state who were not monarchs, leading him to embrace the progressive ideas to which he was exposed. He became an idealist who was always preoccupied with improving the conditions of his countrymen.[citation needed]

Youth and family

His parents were distinguished and wealthy people. Man already, eager to know and living the true democracy, of which he was a fervent lover, traveled through the United States. Back in Bayamo, he found his father had died. He received an immense fortune, everything seemed to smile at him.

In 1848 he married Miss Ana Kindelán y Griñán in Santiago. With her he had ten children. For him, family was one of his main charms. That is why he quite enjoyed taking his daughters to parties and social activities.[4]

The richest man in the East

He owned five hundred slaves and owned rustic farms in Bayamo, Jiguaní, Las Tunas and Manzanillo in which there were several mills and vast areas dedicated to agricultural cultivation and to the raising of Livestock of very diverse type. Their urban estates were not minor. In Bayamo, he owned the city theater, two multi-story houses, many other smaller houses and a grocery store. In Manzanillo, several other houses and a warehouse for honey.

Conspiracies and uprising

In 1851 he participated in the conspiracy of Joaquín de Agüero, nevertheless, shortly after due to lack of coordination and his mother's illness momentarily he backed off from such activities. Aguilera headed the first Cuban Revolutionary Committee, founded in Bayamo, with the participation of Pedro Figueredo (Perucho) and Francisco Maceo Osorio. He directed the meeting that took place in San Miguel de Rompe, on August 3, 1868, without reaching an agreement on the date of the uprising.

In the next meetings it was agreed to postpone it until the end of the harvest season, in order to ensure the necessary resources. Soon after, the persistence of many conspirators led them to meet at the Rosario mill, on which Aguilera did not attend and therefore Carlos Manuel de Céspedes took the lead of the meeting who settled in the Manzanillo area, enjoyed a great hierarchy. From that meeting came the determination to take up arms on October 14, 1868.

The unrest of the conspirators allowed the Spanish authorities to learn about the plans for uprising. They sent groups to arrest the main leaders of the movement. For that reason, Céspedes brought forth the date of operation. He started the fight in the early morning of October 10 at his sugar mill, La Demajagua; while Aguilera, the man who started the movement did not seem to go to war so soon, he was in his Cabaniguán farm. Aguilera had someone who came to him with the news and the intention to persuade him to disavow Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. He agreed, however, with the rest of the members of the Revolutionary Committee and, through Pedro Figueredo, he communicated to Céspedes whom he supported the insurrection.

Guáimaro Assembly and government positions

On April 10, 1869, when the Assembly of Guáimaro was held, Aguilera was not present due to illness. Even the rumor of his death was circulating, for which he was not appointed to any position in the leadership of the government. When Céspedes returned to Bayamo region, he found him alive and appointed him to Secretary of War. Until the beginning of 1870 he held that responsibility and on February 24 of that year the House of Representatives created the position of Vice President of the Republic designating him for the same. A few days later, on March 8, Céspedes appointed him Lugarteniente General of the State of Oriente. He had been awarded the rank of major general before.

Emigration

Céspedes knowing the difficulties that existed abroad to seek help for the Republic of Cuba in Arms and sure of the sympathy that Aguilera enjoyed everywhere, he thought that he could influence the Cuban emigration and political figures from the United States and other countries in order to make future expeditions to Cuba with war material urged by the Cuban forces. On July 27, 1871, together with Ramón de Céspedes, he went on that mission. On the 28th he was in Jamaica and from there he left, as soon as he could, for New York, to take care of the General Agency, the body that directed foreign support for the war. On August 17 he took possession of it.

Aguilera would not take long, to his regret, to collide with the harsh reality. The United States did not recognize the Republic of Cuba in Arms. The situation was getting worse, because the Cubans that Aguilera found in the United States they were divided by interests more personal than patriotic. Some around the reformist Miguel Aldama and others around Manuel de Quesada.

Stay in Europe

In all this year Aguilera did not agree to return to Cuba. He wanted to return to the country with a great expedition that carried many weapons to Cuba and had gone through all possibilities. In 1872 he went to Europe for this purpose. He had faith that the Cubans there would not be so divided looking for their own profits and would go for the Cuban cause.

In 1873 he was back in New York. Soon after, the Chamber deposed President Céspedes. When Aguilera was the vice president, the president of the Chamber, Salvador Cisneros Betancourt, who was acting as the President of the Republic in Arms, wrote to Francisco Vicente Aguilera: "(...) great advantages will be for the country if a man who has not spared sacrifices for his own freedom returns to it (...) You are in a better situation to administer the Republic, come and we will save the Revolution."

Aguilera responded to the President of the Chamber that yes, he would come to Cuba, but when he could lead a strong expedition to the West: "Orient and Camagüey, cradle and guarantee of the Revolution," Aguilera told Cisneros, "are the base of our operations, now the victory is in the West (...) we can kill Spanish soldiers in the East, but the way to conclude the war is to dry up the source from which they spring and we know where that source is."

Insurrectionist

At the time, Spain remained in control of Cuba, but had lost control of several of its territories in Central and South America in the early 19th century. This was mostly due to the efforts of Simón Bolívar, who is credited with leading the fight for independence in what are now the countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia. Colonial rule had its pros and cons. The pros being that the controlling country helped to improve the standard of living in the territory by building out infrastructure, introducing new technologies and implementing systems of governance and organization. The cons were that the controlling country exploited the people under their control with unfair labor practices and exploited the land with little or no recompense to the natives. In Cuba, the Spaniards were forcing the native Indians to work under dreadful conditions in gold mines. In Aguilera's lifetime, the cons were far outweighing the pros and he was very much in favor of the separation of Cuba from Spain.

In 1851, at the age of 30, Aguilera began to conspire against Spanish colonial rule, and joined himself with a movement begun by proto-independence patriot Joaquín de Agüero in Camagüey, Cuba. Henceforth, together with other wealthy landowners of the region, he spoke out openly against colonial Spanish rule. He led an anti-Spanish outbreak that occurred in Bayamo in 1867 and was selected as leader of a General Committee that had been designated to carry out plans for the insurrectionists. The other two members of this committee were Francisco Maceo and Pedro "Perucho" Figueredo, later author of the Cuban National Anthem. Aguilera actively participated in the creation of conspiratorial groups in diverse regions of the country, including the planning of preliminary reunions that culminated in the declaration of independence of October 10, 1868 at Yara, led by planter and lawyer Carlos Manuel de Cespedes. Aguilera took the position that Cespedes' revolt should wait until more money could be raised before attacking, and though his viewpoint did not prevail, he deferred total control of the insurrection and subsequent war to Cespedes, who became de facto leader of the independence movement. Aguilera's support of Cespedes stemmed from both his disinterest in political power, and his desire to improve the lot of his fellow countrymen.

Aguilera put his money where his mouth was. At one of the conspiracy meetings he famously announced that he was ready and willing to sell all his private property at market value to raise funds for arming the new Cuban Army of Independence. The following day, he published an ad in Bayamo's major newspaper offering all his properties, buildings, and livestock, which included 35,000 head of cattle and 4,000 horses, for sale.

Aguilera held many positions in the Cuban Army, including Major General, Minister of War, Vice President of the Republic, and Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern District. While in command of the army he was distinguished for courage and ability, taking part in person in many engagements and skirmishes.

Emancipation of slaves

Upon the outbreak of war in 1868, Aguilera freed all 500 of his slaves, an illegal action under the Spanish law in effect in Cuba at that time, and joined ranks with many of them to retake the city of Bayamo from the Spanish. Many of his ex-slaves became soldiers and officers in the War of Independence.

Death

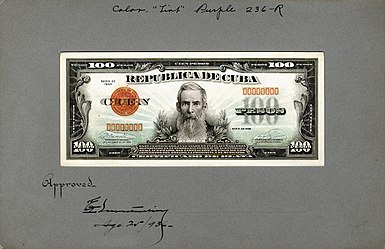

In 1871, Francisco Vicente Aguilera went to New York City to raise funds for the war effort. He had given everything away for the cause of Cuban independence. Aguilera died completely destitute after a brief bout with throat cancer in his apartment at 223 West 30th Street in New York on February 22, 1877. The Cuban Republic, finally free after so many years and casualties, honored Aguilera by printing his image on the Cuban $100 peso bill (pictured above) that was in circulation prior to the 1959 communist revolution.[5][6]

Mausoleum

Aguilera's remains have been kept in Bayamo since 1910. However, the history of the transfer of his remains to his homeland and the consequent burials is so rich that they are well worth another journalistic report.

His remains were taken from the San Juan cemetery so that it would not be transferred to the Santiago necropolis of Santa Ifigenia Cemetery.

In 1958, the mausoleum was inaugurated in his homage. His remains currently rest in its base.

Not far from this, monuments to other illustrious Bayamese rise, and they are collectively called Retablo de los Héroes.

References

- ^ "New York Herald" (PDF).

- ^ "Biography of Francisco Vicente Aguilera (1821-1877)". Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ^ "Francisco Vicente Aguilera: el caballero intachable". Granma.cu (in Spanish). 22 June 2016. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ "Aguilera, Francisco Vicente (1821-1877). » MCNBiografias.com". www.mcnbiografias.com. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ Ramirez, Por Liuba Mustelier. "Historical legacy of Francisco Vicente Aguilera highlighted in Bayamo on the 199 birthday". CMKX Radio Bayamo. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ "Francisco Vicente Aguilera Archivos". La Demajagua (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "Francisco Vicente Aguilera". New York Times. 1877-02-24.