France Balantič

France Balantič | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 29, 1921 Kamnik, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (now in Slovenia) |

| Died | November 24, 1943 (aged 21) Grahovo near Cerknica, Province of Ljubljana |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Literary movement | Symbolism, Expressionism |

France Balantič (29 November 1921 – 24 November 1943)[1] was a Slovene poet. His works were banned from schools and libraries during the Titoist regime in Slovenia, but since the late 1980s he has been re-evaluated as one of the foremost Slovene poets of the 20th century.[citation needed]

Life

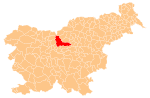

Balantič was born in a working-class family in Kamnik,[2][3] in the Slovenian region of Upper Carniola in what was then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Before World War II, he studied Slavic linguistics at the University of Ljubljana.[3]

As a student, Balantič professed left-wing leanings, with a sympathy towards Christian Socialism and trade unionism in general. As a devout Roman Catholic,[4] he was however suspicious to the materialist world view present in most left-wing ideologies of the time, especially in Communism. By 1941 he had turned away from political activism, convinced that the only salvation for humanity was to be found in the Gospel.

In the first months after the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and the Italian occupation of Ljubljana, he joined the illegal student organization of the Liberation Front of the Slovenian People, but left it soon afterwards, disturbed by its pro-Communist leanings.

In June 1942, the Fascist authorities of the Italian-occupied Province of Ljubljana interned him in the Gonars concentration camp,[3] together with several other nationalist students, including Zorko Simčič and Marjan Tršar. He was released thanks to the intercession of Bishop Gregorij Rožman in autumn of the same year. He returned to Ljubljana, and spent half a year in almost complete seclusion, mostly dedicating himself to writing. In March 1943, he joined the voluntary anti-communist militia sponsored by the Italians. After the Italian armistice in September 1943, he decided to enroll in the Slovenian Home Guard,[3] an anti-communist militia sponsored by various Slovene conservative and anti-revolutionary political groups, which collaborated with the Nazi German occupying forces in the fight against the Slovenian Partisans. He was stationed as an officer at the Home Guard supply post in the village of Grahovo near Cerknica in 1943. The post was attacked, besieged, and burned down in an uneven fight between some 30 Home Guard troops and the ten-times larger Slovene Partisan Tomšič Brigade. Balantič died in the attack.[3]

Work

Balantič was an intimist and lyricist poet who wrote mystical and passionate poems. He was influenced by the work of the Slovene Romantic poet France Prešeren, the decadentist poet Josip Murn, the expressionist Srečko Kosovel, and especially the religious symbolism of Alojz Gradnik. Balantič was a master of classic poetic forms, especially sonnets. His major poem was "Sonetni venec" (The Wreath of Sonnets, written in 1940)[3] and published posthumously by the literary critic Tine Debeljak in 1944.

The most typical trait of Balantič's poetry is his unique blend of personalist and eschatological visions, in which a messianic sense of the tragic dissolution of civilization and the end of time is intertwined with premonitions of his own death and a strong erotic feeling. Most of his poems are a search towards a personal vision of Divinity, in connection with the tradition of Catholic mysticism. He developed a complex metaphorical-hermetical style, verging on manierism. In many ways, Balantič continued the tradition of Slovene Christian expressionism, whose main exponents were Anton Vodnik and Edvard Kocbek, which, following the example of the writer Ivan Pregelj, he connected with elements of Baroque aestheticism.

Legacy

After World War II, all of his poetry was removed from public libraries in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and his name was omitted from public education. When the literary historian Anton Slodnjak mentioned Balantič in his Review of Slovene Literature in the 1950s, he was fired from his post at the University of Ljubljana because of it.[5][6] In 1966, a selection of Balantič's poems were printed under the title Muževna steblika, but after intervention by the Communist Party it was decided that the book should be withdrawn and the entire run was sent to be destroyed and recycled.[7]

His poems were published among the Slovene diaspora, especially in Argentina, where the literary historians Tine Debeljak and France Papež edited and published most of his works. In the late 1980s, Balantič was rediscovered in Slovenia, and he is now considered one of the foremost Slovene-language poets of the 20th century[citation needed], along with Edvard Kocbek and Srečko Kosovel. In 1994, the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts held the Balantičev–Hribovšek Symposium, which also highlighted the banned poet Ivan Hribovšek.[8][9]

Poetry collections

- V ognju groze plapolam (I Flutter in the Fire of Horror; Ljubljana, 1944)

- Muževna steblika (The Sappy Stem; Published posthumously in Buenos Aires, 1966) COBISS 14412545

- Zbrano delo (Collected Work; Buenos Aires, 1976) COBISS 522295

- Zbrane pesmi (Collected Poems; Ljubljana, 1991) COBISS 23614976

- Tihi glas piščali (The Silent Voice of the Flute; Ljubljana, 1991) COBISS 28163840

See also

References

- ^ Lutar Ivanc, Aleksandra. 2006. Album slovenskih književnikov. Ljubljana: Mladinska Knjiga, p. 160.

- ^ Cox, John K. 2004. Slovenia: Evolving Loyalties. London: Routledge.

- ^ a b c d e f Plut-Pregelj, Leopoldina, & Carole Rogel. 2010. The A to Z of Slovenia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, p. 33.

- ^ Cooper, Henry R. 2003. A Bilingual Anthology of Slovene Literature. Bloomington, IN: Slavica, p. 251.

- ^ Hočevar, Ksenja (November 22, 2013). "Balantič, klasik slovenstva". Družina. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Nežmah, Bernard (March 14, 2004). "France Balantič: V ognju groze plapolam". Mladina (10). Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Pibernik, France (2017). Novi Slovenski biografski leksikon. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Hočevar, Ksenja (November 27, 2014). "Repriza Antigone po slovensko". Družina. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Dolgan, Marjan (1994). Balantičev in Hribovškov zbornik. Referati simpozija 20. in 21. januarja 1994. Ljubljana: Inštitut za slovensko literaturo in literarne vede ZRC SAZU. ISBN 961-218-040-7. Retrieved February 21, 2023.