Soda fountain

A soda fountain is a device that dispenses carbonated soft drinks, called fountain drinks. They can be found in restaurants, concession stands and other locations such as convenience stores. The machine combines flavored syrup or syrup concentrate and carbon dioxide with chilled and purified water to make soft drinks, either manually, or in a vending machine which is essentially an automated soda fountain that is operated using a soda gun. Today, the syrup often is pumped from a special container called a bag-in-box (BiB).

Fountain coke is an often confused term normally referring to a handheld dispenser behind a bar or counter that are used in many countries, including Spain, France and the United Kingdom. The term 'fountain' helps differentiate from 'machine' cola, as the fountain is more easily controlled and offers more flavours.

A soda fountain is also referred to as a postmix machine in some markets. Any brand of soft drink that is available as postmix syrup may be dispensed by a fountain.

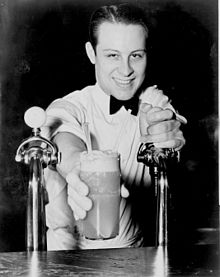

The term may also refer to a small eating establishment, soda shop or luncheonette, common from the late 19th century until the mid-20th century, often inside a drugstore, candy store or other business, where a soda jerk served carbonated beverages, ice cream, and sometimes light meals. The soda jerk's fountain generally dispensed only unflavored carbonated water, to which various syrups were added by hand only.

History

The soda fountain was an attempt to replicate mineral waters that bubbled up from the Earth. Many civilizations believed that drinking, and bathing, in these mineral waters cured diseases. Large industries often sprang up around hot springs, such as Bath in England (43 AD) or the many onsen of Japan.

Although vessels to bottle and transport water were part of the earliest human civilizations,[1] bottling water began in the United Kingdom with the first water bottling at the Holy Well in 1621.[2] The demand for bottled water was fueled in large part by the resurgence in spa-going and water therapy among Europeans and American colonists in the 17th and 18th centuries.[3] The first commercially distributed water in America was bottled and sold by Jackson's Spa in Boston in 1767.[4] Early drinkers of bottled spa waters believed that the water at these mineral springs had therapeutic properties, and that bathing in or drinking the water could help treat many common ailments.[3] Many types of mineral water are sparkling, and thus so were they when bottled.

Early scientists tried to create effervescent waters with curative powers, including Robert Boyle, Friedrich Hoffmann, Jean Baptiste van Helmont, William Brownrigg, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, and David Macbride. In the early 1770s, Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman, and (separately) English scientist Joseph Priestley invented equipment for saturating water with carbon dioxide. In 1774, John Mervin Nooth demonstrated an apparatus that improved upon Priestley's design. In 1807, Henry Thompson received the first British patent for a method of impregnating water with carbon dioxide. This was commonly called soda water, although it contained no sodium bicarbonate.[5]

The soda fountain began in Europe, but achieved its greatest success in the U.S. Benjamin Silliman, a Yale chemistry professor, was among the first to introduce soda water to America. In 1806, Silliman purchased a Nooth apparatus and began selling mineral waters in New Haven, Connecticut. Sales were brisk, so he built a bigger apparatus, opened a pump room, and took in three partners. This partnership opened soda fountains in New York City and Baltimore, Maryland. At roughly the same time, other businessmen opened fountains in New York City and Philadelphia. Although Silliman's business eventually failed, he played an important role in popularizing soda water.[6]

In 1832, John Matthews of New York City and John Lippincott of Philadelphia began manufacturing soda fountains. Both added innovations that improved soda-fountain equipment, and the industry expanded as retail outlets installed newer, better fountains. Other pioneering manufacturers were Alvin Puffer, Andrew Morse, Gustavus Dows, and James Tufts. In 1891 the four largest manufacturers—Tufts, Puffer, Lippincott, and Matthews—formed the American Soda Fountain Company, which was a trust designed to monopolize the industry. The four manufacturers continued to produce and market fountains under their company names. The trust controlled prices and forced some smaller manufacturers out of business.[7]

Before mechanical refrigeration, soda fountains used ice to cool drinks and ice cream. Ice harvesters cut ice from frozen lakes and ponds in the winter and stored the blocks in ice houses for use in the summer. In the early 20th century, new companies entered the soda fountain business, marketing "iceless" fountains that used brine.

The L.A. Becker Company, the Liquid Carbonic Company, and the Bishop & Babcock Company dominated the iceless fountain business. In 1888 Jacob Baur of Terre Haute, Indiana founded the Liquid Carbonics Manufacturing Company in Chicago, becoming the Midwest's first manufacturer of liquefied carbon dioxide. In 1903 Liquid Carbonic began market-testing its prototype iceless fountain in a Chicago confectionery. Louis A. Becker was a salesman who started his own manufacturing business in 1898, making the 20th-Century Sanitary Soda Fountain. In 1904 Becker's company produced its first iceless fountain. In 1908 William H. Wallace obtained a patent for an iceless fountain and installed his prototype in an Indianapolis drugstore. He sold his patent to Marietta Manufacturing Company, which was absorbed by Bishop & Babcock of Cleveland.

Liquid Carbonic spawned another leading soda fountain manufacturer, the Bastian-Blessing Company. Two Liquid Carbonic employees, Charles Bastian and Lewis Blessing, started their company in 1908. The newer manufacturers competed with the American Soda Fountain Company and took a large share of the market. The trust was broken up, and its member companies struggled to stay in business. During World War I, some manufacturers marketed "50% fountains," which used a combination of ice and mechanical refrigeration. In the early 1920s, many retail outlets purchased soda fountains using ammonia refrigeration.[8]

In their heyday, soda fountains flourished in pharmacies, ice cream parlors, candy stores, dime stores, department stores, milk bars and train stations. They served an important function as a public space where neighbors could socialize and exchange community news. In the early 20th century many fountains expanded their menus and became lunch counters, serving light meals as well as ice cream sodas, egg creams, sundaes, and such. Soda fountains reached their height in the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1950, Walgreens, one of the largest chains of American drug stores, introduced full self-service drug stores that began the decline of the soda fountain,[9] as did the coming of the Car Culture and the rise of suburbia. Drive-in restaurants and roadside ice cream outlets, such as Dairy Queen, competed for customers. North American retail stores switched to self-service soda vending machines selling pre-packaged soft drinks in cans, and the labor-intensive soda fountain did not fit into the new sales scheme. Today only a sprinkling of vintage soda fountains survive.

In the Eastern Bloc countries, self-service soda fountains, located in shopping centers, farmers markets, or simply on the sidewalk in busy areas, became popular by the mid-20th century.[10] In the USSR, a glass of carbonated water would sell for 1 kopeck, while for 3 kopecks one could buy a glass of fruit-flavored soda. Most of these vending machines have disappeared since 1990; a few remain, usually provided with an operator.

In literature and popular culture

The arrival of soda fountain establishments in Glasgow, Scotland, was satirised by Neil Munro in his Erchie MacPherson story, "The Soda-Fountain Future", first published in the Glasgow Evening News on 11 October 1920.[11]

See also

- Coca-Cola Freestyle, a soda fountain which uses microdispensing technology.

- Gasogene, a home-use machine which chemically produces carbonated water for sodas.

- Phosphate soda

- Soda shop

- Schmidt's Candy

- SodaStream, a home-use machine which infuses liquids with carbon dioxide.

- Soda syphon, a device for dispensing carbonated water.

- Soda machine (home appliance)

Notes

- ^ Rong, Xu Gan; Fa, Bao Tong. "Primitive-Aged Drinking Vessels". Grandiose Survey of Chinese Alcoholic Drinks and Beverages. Jiangnan University. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Great Malvern Conservation Area: Appraisal and Management Strategy". Malvern Hills District Council: Planning Services. April 2008. p. 5. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ a b Back, William; Landa, Edward; Meeks, Lisa (1995). Bottled Water, Spas, and Early Years of Water Chemistry (Groundwater Volume 33, Issue 4 ed.). p. 606.

- ^ Hall, Noah. "A Brief History of Bottled Water in America". Great Lakes Law. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Funderburg 2002, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Funderburg 2002, pp. 10–17.

- ^ Funderburg 2002, pp. 21–29.

- ^ Funderburg 2002, pp. 114–125.

- ^ Frederick, James (2005). "Back to the future: Walgreens testing soda fountain". Drug Store News. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Hlynsky, David. "Vending Machine". Making the History of 1989. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History & New Media. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Munro, Neil, "The Soda-Fountain Future", in Osborne, Brian D. & Armstrong, Ronald (eds.) (2002), Erchie, My Droll Friend, Birlinn Limited, Edinburgh, pp. 508 – 511, ISBN 9781841582023

References

- Funderburg, Anne Cooper (2002). Sundae Best: A History of Soda Fountains. The University of Wisconsin Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-853-1.

- Funderburg, Anne Cooper (1995). Chocolate, Strawberry, and Vanilla: A History of American Ice Cream. ISBN 0-87972-691-1.

Further reading

- Monk-Tutor, M.; Tutor, T. (2008). Drug Store Soda Fountains of the Southeast. Health Care Logistics.

External links

- "The Drugstore Soda Fountain". Drugstore Museum. Soderlund Village Drug. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15.

- Curtis, Wayne (February 24, 2011). "Phosphate With a Twist". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. — On cherry phosphate