Fort Libéria

| Fort Libéria | |

|---|---|

| Villefranche-de-Conflent in France | |

| |

| Coordinates | 42°35′24″N 2°21′53″E / 42.59°N 2.364722°E |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1681-1683 |

| Built by | Vauban |

Fort Libéria is a former military installation in the French commune of Villefranche-de-Conflent in the department of the Pyrénées-Orientales, at the confluence of the rivers Têt, Rotjà, and Cady. Constructed to defend the newly acquired territory of the Roussillon following the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), it was designed by Louis XIV's military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban on a hill above the village of Villefranche-de-Conflent. The fort was occupied by a garrison of 100 people and their officers, and equipped with ten cannons. It was only attacked once, and lost its military function in the 19th century.

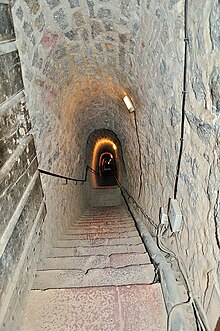

It also functioned as a prison: two of the women accused in the Affair of the Poisons were locked up in the fort in 1682 by order of Louis XIV, and died there after being imprisoned for decades. By 1927 the fort was sold, and for a while served as a retirement home for sailors. In 1984 it was sold to a group of local businessmen, and as of 1987, it is accessible to visitors. The fort, and the 734-step long underground staircase leading to it, is classified by the French state as a monument historique, and it is also listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

History

The fort was constructed by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, the military engineer of Louis XIV, after Catalonia was divided between Spain and France following the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659). Vauban redesigned the fortification of Villefranche-de-Conflent and added six bastions and gate houses to it in 1679, but still considered it vulnerable, and decided to defend it with a fort on the hill called Belloch, behind the city.[1] Libéria was one of a number of forts Vauban built or redesigned between Prats-de-Mollo-la-Preste (Fort Lagarde) and Collioure (Fort Saint-Elme and Château Royal de Collioure). These fortifications (including Mont-Louis and Fort de Bellegarde) were to block access to the Têt and Segre valleys, and were built with angular slopes to resist artillery.[2]

The fort was built between 1681 and 1683.[3] It has two hexagons nested in one another, protected on the mountain side by a counterscarp. It has a triangular donjon towards the south, the side of the village. It deviates from other citadels forts by being completely adapted to the terrain.[4] The underground staircase leading to the village dates from the age of Napoleon III; see belowLater, Libéria, which dominates the village from 160 meters above,[1] was connected to the village by an underground staircase 734 steps long[3] built between 1850 et 1853 on orders of Napoléon III.[5]

Initially, the fort was but poorly manned and equipped, and window coverings were installed so that the few pieces of artillery could be moved from one position to another, giving the impression of more weaponry than was actually present. At some point, though, there was a garrison of 100 people plus officers, and it was equipped with two 12-pound cannons, two 8-pound cannons, and six 4-pound cannons, each with 200 projectiles. The magazine held 12,000 pounds of powder.[3]

The fort was tested only once during military conflict, in early August 1793, during the War of the Pyrenees (a consequence of the French Revolution). The seemingly impregnable fort was captured quickly: Spanish troops set up artillery batteries on the rocks behind the fort, and it was forced to surrender.[6] It was soon recaptured by French troops under Luc Siméon Auguste Dagobert,[2] and in August Spanish general Antonio Ricardos withdrew from the area following the Spanish defeat at the Battle of Peyrestortes.[6] In the second year of the French Republican calendar, repairs were ordered to the parapets and sentry boxes that had been damaged by cannon fire.[7]

It was reinforced under Napoleon III, between 1850 and 1856.[3] He ordered the construction of the underground staircase, 734 steps long, that leads to the village. 22 or more people died during construction. There is a window at the mid-point. Napoleon also had a battery of five casemates built from which the three roads to Villefranche could be covered with guns.[5] The fort was abandoned later in the 19th century.[3] By 1927 the Direction de l'Immobilier de l'État had sold the fort,[8] and its new owner attempted to turn it into a retirement home for sailors. He razed the barracks on the first level of the fort in order to make a courtyard. Because of the difficult access for elderly people and its distance from the sea, his plan was not successful.[3] It was again sold in 1957 and bought by Marcel Puy; in 1984, Puy signed it over to four businessmen from the city via an emphyteusis, and after three years of restoration the fort was opened to the public in 1987.[8]

Prison

On multiple occasions the fort served as a prison for women, with a "prison pour dame" equipped for the purpose.[3] During the Villefranche Conspiracy, which took place during a widespread popular revolt against the efforts of Louis XIII and then Louis XIV to bring the formerly Catalan area under French control,[9] Inès de Llar was held at Libéria.[3] Her family were Catalan and had plotted to kill the French garrison in Villefranche, but Inès was in love with a French officer, and warned him, after which the plot was discovered; her family was beheaded, but she was only sent to a convent.[9]

A decade later, the Affair of the Poisons led Louis XIV to have a number of people implicated in it imprisoned for life through a lettre de cachet. Anne Guesdon (Madame de Brinvilliers's chambermaid) and Magdelaine Chapelain were both imprisoned at the fort.[10] Guesdon died there in 1717, after 36 years of imprisonment;[11] Chapelain died in 1724.[12] In 1717, after the death of Guesdon on 30 August 1717, Villefranche's commander noted that Guesdon had died, that originally there had been four women imprisoned there "for poison", and that one, "la Chappelain", not less old than Guesdon, still remained. Guesdon, he noted, had managed to save up 45 French livres from her daily allotment of eight sols for food; she requested that her cellmate be given as much as she needed, and the remainder was to be used for prayer.[12]

Monument historique, access

The fort was classified as a monument historique in April 2009.[4] It is also classified as one of the Fortifications of Vauban UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[13]

The fort is open to the public. Access is either on foot, via a sometimes steep road; by minibus; or by the subterranean staircase.[3]

Film location

The fort Libéria was the backdrop for the 1959 film Le Bossu, by André Hunebelle.[14]

Gallery

- Afternoon view

- Fort Libéria

- Chapel and courtyard

- Barracks for underofficers

See also

References

- ^ a b Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2009). Vauban and the French Military Under Louis XIV: An Illustrated History of Fortifications and Strategies. McFarland. pp. 223–25. ISBN 9780786456987.

- ^ a b Carr, Matthew (2018). The Savage Frontier: The Pyrenees in History and the Imagination. The New Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9781620974285.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Fort Libéria". Les Pyrénées Orientales (in French). Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Fort Libéria (également sur commune de Fuilla)" (in French). Ministry of Culture. 1992. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Souterrain des "1000 marches"". Fort Liberia (in French). Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ a b Prats, Bernard (8 August 2007). "Villefrance de Conflent, La Tête et la Clef" (in French). Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "Révolution Française". Fort Liberia (in French). Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Fin XIX° à nos jours". Fort Liberia (in French). Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ a b Marcet, Alice (1974). "Les conspirations de 1674 en Roussillon : Villefranche et Perpignan". Annales du Midi. 86 (118): 275–296. doi:10.3406/anami.1974.4877.

- ^ "La Prison des Dames – Affaire des Poisons". Fort Liberia (in French). Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Lebigre, Arlette (2006). 1679-1682, l'affaire des poisons. Editions Complexe. p. 142. ISBN 9782804800949.

- ^ a b Funck-Brentano, Frantz (1900), Le drame des poisons: études sur la société du XVII ̇siècle et plus particulièrement la cour de Louis XIV d'après les archives de la Bastille (3 ed.), Hachette, p. 244

- ^ "Fortifications of Vauban". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Grand Sud Insolite – La cité en bas, le fort en haut et un escalier-souterrain record

External links

- Base Mérimée: PA00104149, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Site web du fort

- Chemins de mémoire : Le fort Libéria