Fort Wetherill

| Fort Wetherill | |

|---|---|

| Part of Harbor Defenses of Narragansett Bay | |

| Jamestown, Rhode Island | |

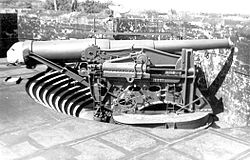

12-inch gun on disappearing carriage, similar to those at Fort Wetherill. | |

| Type | Coast Artillery Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1895–1903 |

| In use | 1900–1945 |

| Materials | reinforced concrete |

| Battles/wars | World War I, World War II |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Col. Earl C. Webster |

Fort Dumpling Site | |

Fort Dumpling, Rhode Island by George L. Clough, Brooklyn Museum | |

| Location | 3 Fort Wetherill Road Jamestown, Rhode Island |

| Coordinates | 41°28′38″N 71°21′28″W / 41.477325°N 71.35783°W |

| Built | 1800–1941 |

| Architect | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000021[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 16, 1972 |

Fort Wetherill is a former coast artillery fort that occupies the southern portion of the eastern tip of Conanicut Island in Jamestown, Rhode Island. It sits atop high granite cliffs, overlooking the entrance to Narragansett Bay. Fort Dumpling from the American Revolutionary War occupied the site until it was built over by Fort Wetherill. Wetherill was deactivated and turned over to the State of Rhode Island after World War II and is now operated as Fort Wetherill State Park, a 51-acre (210,000 m2) reservation managed by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

Early history

In 1776, an 8-gun earthwork fortification was constructed by patriot forces at the site of Dumpling Rock, which overlooks the strategic East Passage toward Newport. This old fort was occupied by American, British, and French forces for various periods of time during the American Revolutionary War. The patriots called it the Dumpling Rock Battery; the British called it Fort Dumpling Rock. The British abandoned it in 1779 when they evacuated Newport, and after this it was called Fort Conanicut (not to be confused with the Conanicut Battery on the other side of the island near Beaver Head).[2]

In 1798, construction was started on a permanent fortification at Dumpling Rock under the supervision of Major Louis Tousard of the Army Corps of Engineers. This fort was officially called Fort Louis and, later, Fort Brown (after Major General Jacob Brown, commanding general of the United States Army, or possibly after its Revolutionary War commander Abdiel Brown),[3] but it was commonly called Fort Dumpling throughout its existence. Fort Dumpling was in the form of an oval stone tower and was frequently used as an artistic motif and a place for social outings. The fort was mentioned in the Secretary of War's report on fortifications for December 1811 as being at "the Dumplins" and is described as "a circular tower of stone, with casemates... with a small expense, there can be mounted six or eight heavy guns; and now in an unfinished state".[4]

Modern history

In 1899, the U.S. government purchased additional land during the Endicott period of coastal fortification, and built Fort Wetherill at the site of Fort Dumpling. Fort Wetherill was the largest fort of the Coast Defenses of Narragansett Bay (Harbor Defenses after 1925). It was named for Captain Alexander Macomb Wetherill, a Jamestown native who was killed in action during the Battle of San Juan Hill. Fort Dumpling was destroyed in the process of building the new fort, which featured numerous concrete emplacements for 20th-century breech-loading, rifled coast artillery pieces.

In 1901, Battery Varnum was the first modern battery to be completed, mounting two 12-inch guns on barbette carriages and situated in the far southeast corner of the fort. By 1910, the other six batteries in the fort's pre-World War II arsenal had been brought into service. Several of these batteries are now overgrown with brush, but they offer what is perhaps the longest linear concrete gun line in the coast defenses of New England.

During World War I, the fort was garrisoned by five companies of the Rhode Island National Guard. After the war, Fort Wetherill reverted to "caretaker status," with only a single Coast Artillery sergeant assigned to watch over it and other nearby facilities. Fort Wetherill was reactivated by the U.S. Army in September 1940 as a major part of the Harbor Defenses of Narragansett Bay, and new barracks were built to house the National Guard's 243rd Coast Artillery Regiment and its 1,200 soldiers. The 10th Coast Artillery Regiment of the Regular Army also garrisoned forts in Rhode Island 1924–45. The fort also functioned in the year before World War II as a military training facility, and late in the war as a training center for German prisoners of war. However, the big guns of the Endicott era were mostly scrapped by 1943, as Fort Wetherill was superseded by new defenses centered on Fort Greene and Fort Church. In 1946, the U.S. military ceased operations at Fort Wetherill, and the site remained abandoned for the quarter century that followed.

The State of Rhode Island officially acquired the fort on 16 August 1972 and reconfigured the site for public use as a state park. In 1972, the site was also added to the National Register of Historic Places. The park continues to attract visitors with a variety of modern recreational uses. The property offers walking trails through wooded areas and along the rocky coast, and is a popular destination for scuba diving.

Another distinctive feature of the fort is its surviving buildings and tramway system that were once used in the submarine mining operation that was run from the fort during World War 1 and World War 2. During World War 2, some 300 mines were planted on the east and west sides of Conanicut Island, protecting the approaches to Newport, and almost all of these were maintained from the Mine Wharf at Fort Wetherill. The image shows the old mine storehouse, one of the best preserved in the United States, with the remains of the tram tracks that used to carry the massive mines in and out of its front door. Mine launches would tie up at the nearby wharf, load the mines that were to be laid, transport them to the inlet, and lay them, together with their electric cables. Then, when these mines needed to be taken in, they were ferried back to the wharf and transported on the tramway to the various service buildings. A dual mine observation station sat atop the hill between the storehouse and Battery Varnum.[5] Spotters manned this station and others scattered around the harbor defenses, and could locate enemy ships approaching the minefields, signaling to the operators in the mining casemate when a given mine was to be electrically detonated.[6]

Modern armament

Beginning in the early 20th century, the seven major concrete gun batteries listed below were built and armed at Fort Wetherill.[7] During World War II, Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) Battery 923 was built, consisting of two fixed 90 mm guns plus two mobile 90 mm guns on platforms that remained from an earlier antiaircraft gun battery, along with two 37 mm guns. This battery was previously at Brenton Point in Newport until July 1944.[8] Battery 924, with two 90 mm guns on mobile mounts, was also at the fort.[9] Only Batteries Dickenson and Crittenden (plus the AMTB battery) were operational during World War II.[10] New batteries at Fort Church and Fort Greene included 16-inch guns which superseded most of Fort Wetherill's batteries.

The batteries at Fort Wetherill were:[11][9]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varnum | 2 | 12-inch gun M1888 | barbette M1892 | 1901–1943 |

| Wheaton | 2 | 12-inch gun M1900 | disappearing M1901 | 1908–1943 |

| Walbach | 3 | 10-inch gun M1888 | disappearing M1896 | 1908–1936 |

| Zook | 3 | 6-inch gun M1903 | disappearing M1903 | 1908–1917 |

| Dickenson | 2 | 6-inch gun M1900 | pedestal M1900 | 1908–1947 |

| Crittenden | 2 | 3-inch M1902 seacoast gun | pedestal M1902 | 1908–1946 |

| Cooke | 2 | 3-inch gun M1898 | masking parapet M1898 | 1901–1920 |

| AMTB 923 | 4 | 90 mm gun | two fixed T3/M3, two mobile | 1944–1946 |

| AMTB 924 | 2 | 90 mm gun | mobile | 1944–1946 |

Battery Varnum was named for James Mitchell Varnum, a Revolutionary War general from Rhode Island. Battery Wheaton was named for Frank Wheaton, a Civil War general from Rhode Island. Battery Walbach was named for John de Barth Walbach, a career Army officer of the American Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and the Mexican–American War. Battery Zook was named for Samuel K. Zook, a Civil War general. Battery Dickenson was named for George Dickenson, an artillery officer killed in the Civil War. Batteries Crittenden and Cooke were named for two officers killed in the Battle of the Little Big Horn, also called "Custer's Last Stand".

After the US entered World War I, Battery Zook's three 6-inch guns were removed for service on field carriages on the Western Front in 1917 and were never returned to the fort. Records show that the guns arrived in France, but a history of the Coast Artillery in World War I states that none of the regiments in France equipped with 6-inch guns completed training in time to see action before the Armistice.[12]

Battery Walbach's three 10-inch guns were also dismounted in 1917 for potential use as railway guns, but two were soon remounted while the third was transferred to nearby Fort Greble in December 1918. The remaining two guns were eventually transferred to Fort H. G. Wright on Fisher's Island, New York in 1936.

Battery Cooke was disarmed in 1920 as part of a general removal from service of the 3-inch gun M1898. The "masking parapet" carriage unique to that weapon was a retractable pedestal carriage. Battery Crittenden's M1902 guns were placed in storage in 1925, but were replaced that year by two 3-inch M1903 guns from Battery Belton at Fort Adams in Newport.

Battery Varnum's guns were scrapped in 1943 as part of a general scrapping of older heavy weapons once new 16-inch gun batteries were completed. Battery Wheaton was probably also removed from service at this time, but for some reason its guns were exempted from scrapping until the war ended.

Battery Dickenson was retained in service throughout World War II along with other 6-inch pedestal batteries, as this mounting could track enemy vessels better than disappearing mounts. The battery lacked a modern gun data computer during World War II and received its fire control radar data from Set 296–9, an SCR-296 radar located at Brenton Point, off Ocean Avenue in Newport.

Current uses

Fort Wetherill was acquired by the state of Rhode Island and quickly became a location for sightseeing. It is popular to view the Tall Ships America event that takes place in Narragansett Bay every summer, and was popular for the America's Cup sailing races prior to 1984. The park offers parking facilities, public restrooms, and picnic tables.

As of 2016, most batteries have been partly buried to the loading platform level for safety in visiting. There is considerable spalling of exterior concrete surfaces. The mine storehouse area is well preserved and restored, with several interpretive plaques describing the mine and net defense systems in Narragansett Bay. As of 2020, most of the surface of the fort is covered in graffiti.

See also

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- 10th Coast Artillery (United States)

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Newport County, Rhode Island

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Fort Conanicut at American Forts Network

- ^ Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. p. 706. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- ^ Wade, p. 243

- ^ All that remains today of this former cemesto board structure are the two octagonal concrete columns that served as the foundations for the depression range finders (DPFs) mounted atop them. One of these columns has a modern communications mast affixed to it.

- ^ During WW2, both minefields protecting Newport were controlled from a Mining Casemate (at Location 42/Site 1B) northwest of Hull Cove and west of Beavertail Road in what is now Beavertail State Park.

- ^ Coast Defense Study Group. The terminal dates listed for each battery are those at which the Army formally declared that battery surplus, but in fact, the battery may have been rendered non-operational long before.

- ^ Schroder, p. 70

- ^ a b Schroder, p. 120

- ^ Battery Wheaton's two 12-inch guns on disappearing carriages seem to have remained in place during WW2, being excluded from the scrapping program. They were not considered part of the harbor's WW2 defenses.

- ^ Berhow, p. 205

- ^ History of the Coast Artillery Corps in WWI

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Second ed.). CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Schroder, Walter K. (1980). Defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II. East Greenwich, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society. ISBN 0-917012-22-4.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794–1815. CDSG Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

Image gallery

- Due to decay and structural damage several parts of the fort are fenced off (February 2006)

- A room on the first floor (February 2006)

- Fort Wetherill in 2008.

- Fort Wetherill in 2008.

- Fort Wetherill as of October 2010

- The platform of Gun 2 at Battery Dickenson

- Battery Zook, October 2010

- Fort Wetherill as of October 2010

- Fort Wetherill as of October 2010 (The fort is just behind the trees)

- Battery Varnum, February 2011

- The Mining Casemate at the east end of Battery Zook

- 12-inch disappearing gun emplacement, Battery Wheaton

- Diagram of mine, net, boom, and magnetic detection defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II.

- 12-inch Disappearing Gun emplacement

External links

- Fort Wetherill State Park Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Parks and Recreations Division

- History of the Fort Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Parks and Recreations Division

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- Fort Wetherill at FortWiki