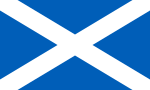

Flag of Nova Scotia

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Adopted |

|

| Design | A white field with the blue diagonal cross that extends to the corners of the flag and the royal arms of Scotland superimposed at the centre of the cross. |

The flag of Nova Scotia consists of a blue saltire on a white field defaced with the royal arms of Scotland. Adopted in 1929 after a royal warrant was issued, it has been the flag of the province since January 19 of that year. It is a banner of arms modelled after the province's coat of arms. Utilized as a pennant since 1858, it was officially recognized under primary legislation as Nova Scotia's flag in 2013. When flown with the flags of other Canadian provinces and the national flag, it is fourth in the order of precedence.

History

The Scottish first settled in modern-day Nova Scotia after 1621,[1] when James VI and I (King of Scotland and England) conferred the land to William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling, via royal charter and gave it the Latin name for "New Scotland".[2][3] Four years later, the colony was granted its own coat of arms by Charles I,[4] with the emblem first recorded at the Court of the Lord Lyon in Edinburgh on May 28, 1625.[5][6] Towards the end of that same decade, the Scots established two short-lived settlements there that were ultimately unsuccessful. Sovereignty over the territory subsequently changed hands between the French and the British throughout the 17th century. This continued until 1713, when the Peace of Utrecht saw France permanently relinquish mainland Nova Scotia to the United Kingdom.[2][3]

The flag of Nova Scotia was reportedly first flown on its merchant vessels during the Age of Sail in the 19th century,[5][7] but vexillologist Whitney Smith opines that these ambiguous accounts are doubtful.[5] The first documented usage of the coat of arms of Nova Scotia as a banner of arms was in June 1858 during a celebratory tribute at a cricket club, as stated by an article in the Acadian Recorder at the time and recounted in the Provincial Flag Act.[8] Nova Scotia later acquiesced to a federation with the other colonies of New Brunswick and the United Province of Canada in 1867 under the British North America Act to form the Dominion of Canada.[2][3] There was vociferous sentiment against Confederation in some parts of Nova Scotia, with a few of its residents flying flags at half-mast on July 1, 1867.[3] The four provinces comprising the new Dominion were allocated individual coats of arms.[9] However, the College of Arms, the heraldic authority in England, was apparently unaware of the earlier grant of arms to Nova Scotia in 1625. Consequently, Queen Victoria issued a Royal Warrant on May 26 of the following year, conferring a different coat of arms on the new province. This consisted of a salmon and three thistles.[5]

The new coat of arms, however, did not become popular in Nova Scotia. As a result, an Order in Council was promulgated by the province's Lieutenant Governor on March 7, 1928, asking for the reinstatement of the 1625 arms.[5] A Royal Warrant was subsequently issued by George V on January 19, 1929, granting the request.[5][10] It was the first flag in the overseas Commonwealth to be approved by royal charter[4][7] – thus purportedly making it the oldest flag of a Dominion[11] – and is the oldest provincial flag in Canada.[12] However, it is not the first Canadian provincial flag to be officially adopted, a distinction held by the flag of Quebec,[13] which was approved by the Parliament of Quebec on March 7, 1950, two years after the order in council was announced.[14]

In a 2001 online survey conducted by the North American Vexillological Association, Nova Scotia's flag ranked within the top sixth of state, provincial and territorial flags from Canada, the United States, and select current and former territories of the United States. It finished in 12th place out of 72, and placed second among Canadian flags after Quebec.[15][16] Twelve years later, the flag was officially recognized as the flag of the province under an Act of Legislature. This came about after an eleven-year-old student from Canso uncovered this aberration while conducting research for a school project.[17][18] Unlike the flags of British Columbia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island – which are also provincial flags that are banner of arms – Nova Scotia's was never recognized as such under a provincial statute.[19] The student contacted the member of the Legislative Assembly representing her electoral district, Jim Boudreau, who consulted with the Legislative Library and other government bodies to ascertain that such a law was not on the books.[17][19] He consequently introduced the bill that became the Provincial Flag Act after receiving royal assent on May 10, 2013.[8] The student and her family were invited to the House of Assembly that same month in acknowledgment of her efforts.[19]

Design

Description

The flag of Nova Scotia has an aspect ratio of 1:2.[4] The blazon for the banner of arms – as outlined in the letters patent registering it with the Canadian Heraldic Authority on July 20, 2007 – reads, "Argent a saltire Azure, overall on an escutcheon Or a lion rampant within a double tressure flory-counter-flory Gules".[6] The official colour scheme, according to the website of the Government of Nova Scotia, follows approximately the Pantone Matching System as indicated below. The colour numbers for the flag's white shade are not specified.[20]

| Colour | Pantone | RGB values | Hex |

|---|---|---|---|

Blue |

293[20] | 0-61-165[21] | #003DA5[21] |

Yellow |

122[20] | 254-209-65[22] | #FED141[22] |

Red |

186[20] | 200-16-46[23] | #C8102E[23] |

Symbolism

The colours and symbols of the flag carry cultural, political, and regional meanings. According to historians Ian McKay and Robin Bates, the Cross of Saint Andrew alludes to divine providence and its part in enabling Scottish immigrants to be "the first among the Nova Scotians".[24] The royal arms epitomize feudal times in Scotland and how this sowed the seeds of the province's constancy as a society.[24] Taken altogether, the saltire and the royal arms signify how Nova Scotia was formerly a colony of the Kingdom of Scotland with the backing of its royal family (the House of Stuart).[6]

Similarities

The Nova Scotian flag has a conspicuous resemblance to both the national flag and the Royal Banner of Scotland.[6][25] The shield is also identical to the royal arms of Scotland.[6] This is due to Nova Scotia's aforementioned historical connections to the country.[6][24] The colours of Saint Andrew's Cross were reversed on the province's flag in order to bring about a more distinct contrast with the royal arms, as stated by Whitney Smith.[5]

Protocol

Advice regarding flag etiquette is the responsibility of the province's Protocol Office.[26] When flown together with the flag of Canada and the other provincial and territorial flags, the flag of Nova Scotia is fourth in the order of precedence (after the national flag and, in descending order of precedence, the flags of Ontario and Quebec, and ahead of New Brunswick).[27] Even though Nova Scotia entered into Confederation on the same date as those three provinces (July 1, 1867), it is placed third among the group since its size of population at the time was the third-largest.[28]

See also

References

- ^ "The Scottish Colonisation of Nova Scotia". Historic UK. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b c O'Grady, Brendan Anthony; Moody, Barry (April 6, 2021). "Nova Scotia – History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Beck, J. Murray (April 7, 2009). "Nova Scotia". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Nova Scotia's provincial symbols". Department of Canadian Heritage. Government of Canada. August 15, 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Whitney (January 21, 2019). "Flag of Nova Scotia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Province of Nova Scotia [Civil Institution]". Canadian Heraldic Authority. The Governor General of Canada. July 20, 2007. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Symbols – The Flag of Nova Scotia". Nova Scotia House of Assembly. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ a b The Provincial Flag Act (9). Nova Scotia House of Assembly. 2013. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Whitney (January 26, 2001). "Flag of New Brunswick". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Nova Scotia (NS) – Facts, Flags and Symbols". Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Government of Canada. November 12, 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Kindersley Ltd., Dorling (6 January 2009). Complete Flags of the World. Penguin. p. 9. ISBN 9780756654863.

- ^ Owens, Ann-Maureen; Yealland, Jane (2014). Our Flag: The Story of Canada's Maple Leaf. Kids Can Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781771381116.

- ^ "Politics and Government". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

Québec's flag, the Fleurdelisé … was the first provincial flag officially adopted in Canada.

- ^ Smith, Whitney (February 28, 2018). "Flag of Quebec". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Kaye, Ted (June 10, 2001). "New Mexico tops state/provincial flags survey, Georgia loses by wide margin". Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "Flag-lovers flower Quebec's fleur-de-lis with a rosy ranking". NewsBank. June 2001. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ a b "Nova Scotia's provincial flag confirmed 155 years later". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Taube, Michael (July–August 2013). "A Neglected Royal". Literary Review of Canada. Toronto. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Hansard Transcript – Assembly 61, Session 5". Nova Scotia House of Assembly. May 7, 2013. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Public Flag, Tartan Images". Communications Nova Scotia. Government of Nova Scotia. May 29, 2007. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ^ a b "Pantone 293 C". Pantone LLC. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Pantone 122 C". Pantone LLC. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Pantone 186 C". Pantone LLC. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c McKay, Ian; Bates, Robin (2010). In the Province of History: The Making of the Public Past in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. McGill–Queen's University Press. p. 312. ISBN 9781877460463.

- ^ Vachon, Auguste (March 4, 2015). "Provincial and Territorial Emblems". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Protocol Office". Government of Nova Scotia. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Position of honour of the National Flag of Canada – With flags of the Canadian provinces and territories". Department of Canadian Heritage. Government of Canada. January 9, 2018. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Did you know…?". Department of Canadian Heritage. Government of Canada. December 17, 2019. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

External links

- Arms and flag of Nova Scotia in the online Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges