Magellan expedition

Nao Victoria, the only ship in the fleet to complete the circumnavigation. Detail from a map by Abraham Ortelius, 1590. | |

| Country | Spain |

|---|---|

| Leader | Ferdinand Magellan others Juan Sebastián Elcano |

| Start | Sanlúcar de Barrameda 20 September 1519 |

| End | Sanlúcar de Barrameda 6 September 1522 |

| Goal | Find a western maritime route to the Spice Islands |

| Ships |

|

| Crew | Approx. 270 |

| Survivors |

|

| Achievements |

|

| Route | |

Route taken by the expedition, with milestones marked | |

The Magellan expedition, sometimes termed the Magellan–Elcano expedition, was a 16th-century Spanish expedition planned and led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan. One of the most important voyages in the Age of Discovery—and in the history of exploration—its purpose was to cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to open a trade route with the Moluccas, or Spice Islands, in present-day Indonesia.[1][2][3] The expedition departed Spain in 1519 and returned there in 1522 led by Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano, who crossed the Indian Ocean after Magellan's death in the Philippines.[4][3] Totaling 60,440 km, or 37,560 mi,[5] the nearly three-year voyage achieved the first circumnavigation of Earth in history.[2] It also revealed the vast scale of the Pacific Ocean and proved that ships could sail around the world on a western sea route.[3][6]

The expedition accomplished its primary goal—to find a western route to the Spice Islands. The five-ship fleet left Spain on 20 September 1519[2] with about 270 men. After sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, the ships continued south along the eastern coast of South America, and eventually discovered the Strait of Magellan, allowing the fleet to pass through to the Pacific Ocean, which Magellan himself named Mar Pacifico.[3][2][7] The fleet completed the first Pacific crossing, stopped in the Philippines, and eventually reached the Moluccas after two years. A much-depleted crew led by Elcano finally returned to Spain on 6 September 1522,[2] having sailed west across the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope through waters controlled by the Portuguese, and north along the west African coast to finally arrive in Spain.[3]

The expedition endured many hardships, including sabotage and mutinies by the mostly Spanish crew (and Elcano himself), starvation, scurvy, storms, and hostile encounters with indigenous people. Only about 40 men and one ship (the Victoria) completed the circumnavigation.[n 1] Magellan himself died in battle in the Philippines and was succeeded as captain-general by a series of officers, with Elcano eventually leading the Victoria's return trip.

The expedition was funded mostly by King Charles I of Spain, with the hope that it would discover a profitable western route to the Spice Islands, as the eastern route was controlled by Portugal under the Treaty of Tordesillas. Although the expedition did find a route, it was much longer and more arduous than expected and was therefore not commercially useful. Nevertheless, the expedition is regarded as one of the greatest achievements in seamanship and had a significant impact on the European understanding of the world.[8][9][3]

Background

Christopher Columbus's voyages to the West (1492–1504) had the goal of reaching the Indies and establishing direct commercial relations between Spain and the Asian kingdoms. The Spanish soon realized that the lands of the Americas were not a part of Asia, but another continent. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas reserved for Portugal the eastern routes that went around Africa, and Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese arrived in India in 1498.

Given the economic importance of the spice trade, Castile (Spain) urgently needed to find a new commercial route to Asia. After the Junta de Toro conference of 1505, the Spanish Crown commissioned expeditions to discover a route to the west. Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa reached the Pacific Ocean in 1513 after crossing the Isthmus of Panama, and Juan Díaz de Solís died in Río de la Plata in 1516 while exploring South America in the service of Spain.

Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese sailor with previous military experience in India, Malacca, and Morocco. A friend, and possible cousin, with whom Magellan sailed, Francisco Serrão, was part of the first expedition to the Moluccas, leaving from Malacca in 1511.[10] Serrão reached the Moluccas, going on to stay on the island of Ternate and take a wife.[11] Serrão sent letters to Magellan from Ternate, extolling the beauty and richness of the Spice Islands. These letters likely motivated Magellan to plan an expedition to the islands and would later be presented to Spanish officials when Magellan sought their sponsorship.[12]

Historians speculate that, beginning in 1514, Magellan repeatedly petitioned King Manuel I of Portugal to fund an expedition to the Moluccas, though records are unclear.[13] It is known that Manuel repeatedly denied Magellan's requests for a token increase to his pay, and that in late 1515 or early 1516, Manuel granted Magellan's request to be allowed to serve another master. Around this time, Magellan met the cosmographer Rui Faleiro, another Portuguese subject nursing resentment towards Manuel.[14] The two men acted as partners in planning a voyage to the Moluccas which they would propose to the king of Spain. Magellan relocated to Seville, Spain in 1517, with Faleiro following two months later.

On arrival in Seville, Magellan contacted Juan de Aranda, factor of the Casa de Contratación. Following the arrival of his partner Rui Faleiro, and with the support of Aranda, they presented their project to the king Charles I of Spain (future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). Magellan's project, if successful, would realise Columbus' plan of a spice route by sailing west without damaging relations with the Portuguese. The idea was in tune with the times and had already been discussed after Balboa's discovery of the Pacific. On 22 March 1518, the king named Magellan and Faleiro captains general. He also raised them to the rank of Commander of the Order of Santiago. They reached an agreement with King Charles which granted them, among other things:[15]

- Monopoly of the discovered route for a period of ten years.[16][17]

- Their appointment as governors (adelantado) of the lands and islands found, with 5% of the resulting net gains, inheritable by their partners or heirs.[16][18]

- A fifth of the gains from the expedition.[16]

- The right to ship 1,000 ducats worth of goods from the Moluccas to Spain annually exempt from most taxes.[17]

- In the event that they discovered more than six islands, one fifteenth of the trading profits with two of their choice,[16] and a twenty-fifth from the others.[19]

The expedition was funded largely by the Spanish Crown, which provided ships carrying supplies for two years of travel. Though King Charles I was supposed to pay for the fleet he was deeply in debt, and he turned to the House of Fugger.[citation needed] Through archbishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, head of the Casa de Contratación, the Crown obtained the participation of merchant Cristóbal de Haro, who provided a quarter of the funds and goods to barter.

Expert cartographers Jorge Reinel and Diego Ribero, a Portuguese who had started working for King Charles in 1518[20] as a cartographer at the Casa de Contratación, took part in the development of the maps to be used in the travel. Several problems arose during the preparation of the trip, including lack of money, the king of Portugal trying to stop them, Magellan and other Portuguese incurring suspicion from the Spanish, and the difficult nature of Faleiro.[21]

Construction and provisions

The fleet, consisting of five ships with supplies for two years of travel, was called the Armada del Maluco, or Armada de Molucca, after the Indonesian name for the Spice Islands.[22][2] The ships were mostly black, due to the tar covering most of their surface. The official accounting of the expedition put the cost at 8,751,125 maravedis, including the ships, provisions, and salaries.[23]

Food was a hugely important part of the provisioning. It cost 1,252,909 maravedis, almost as much as the cost of the ships. Four-fifths of the food on the ship consisted of just two items – wine and hardtack.[24]

The fleet also carried flour and salted meat. Some of the ships' meat came in the form of livestock; the ship carried seven cows and three pigs. Cheese, almonds, mustard, and figs were also present.[25] Carne de membrillo,[26] made from preserved quince, was a delicacy enjoyed by captains which may have unknowingly aided in the prevention of scurvy.[27]

Ships

The fleet initially consisted of five ships, with Trinidad being the flagship. All or most were carracks (Spanish "carraca" or "nao"; Portuguese "nau").[n 2] The Victoria was the only ship to complete the circumnavigation. Details of the ships' configuration are not known, as no contemporary illustrations exist of any of the ships.[30] The official accounting of the Casa de Contratación put the cost of the ships at 1,369,808 maravedis, with another 1,346,781 spent on outfitting and transporting them.[31]

| Ship | Captain | Crew | Tonnage[n 3] (tonels) |

Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trinidad | Ferdinand Magellan | 62 then 61 after a stop-over in Tenerife[34] | 110 | Departed Seville with other four ships 10 August 1519. Broke down in Moluccas, December 1521 |

| San Antonio | Juan de Cartagena | 55[35] | 120 | Deserted in the Strait of Magellan, November 1520,[36] returned to Spain on 6 May 1521[37] |

| Concepción | Gaspar de Quesada | 44 then 45 after a stop-over in Tenerife[38] | 90 | Scuttled in the Philippines, May 1521 |

| Santiago | João Serrão | 31 then 33 after a stop-over in Tenerife[39] | 75 | Wrecked in storm at Santa Cruz River, on 22 May 1520[40][41] |

| Victoria | Luis Mendoza | 45 then 46 after a stop-over in Tenerife[42] | 85 | Successfully completed circumnavigation, returning to Spain in September 1522, captained by Juan Sebastián Elcano. Mendoza was killed during a mutiny attempt. |

Crew

The crew consisted of about 270 men,[43] mostly Spaniards. Spanish authorities were wary of Magellan, so that they almost prevented him from sailing, switching his mostly Portuguese crew to mostly men of Spain. In the end, the fleet included about 40 Portuguese,[44] among them Magellan's brother-in-law Duarte Barbosa, João Serrão, Estêvão Gomes and Magellan's indentured servant Enrique of Malacca. Crew members of other nations were also recorded, including 29 Italians, 17 French, and a smaller number of Flemish, German, Greek, Irish, English, Asian, and black sailors.[45] Counted among the Spanish crew members were at least 29 Basques (including Juan Sebastián Elcano), some of whom did not speak Spanish fluently.[45]

Ruy Faleiro, who had initially been named co-captain with Magellan, developed mental health problems prior to departure (or, as other sources state, chose to remain behind after performing a horoscope reading indicating that the voyage would be fatal for him[46]) and was removed from the expedition by the king. He was replaced as the fleet's joint commander by Juan de Cartagena and as cosmographer/astrologer by Andrés de San Martín.

Juan Sebastián Elcano, a Spanish merchant ship captain living in Seville, embarked seeking the king's pardon for previous misdeeds. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar and traveller, asked to be on the voyage, accepting the title of "supernumerary" and a modest salary. He became a strict assistant of Magellan and kept a journal. The only other sailor to keep a running account during the voyage would be Francisco Albo, who kept a formal nautical logbook. Juan de Cartagena, suspected illegitimate son of archbishop Fonseca, was named Inspector General of the expedition, responsible for its financial and trading operations.[47]

Crossing the Atlantic

On 10 August 1519, the five ships under Magellan's command left Seville and descended the Guadalquivir River to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, at the mouth of the river. There they remained more than five weeks. Finally they set sail on 20 September 1519 and left Spain.[48]

On 26 September, the fleet stopped at Tenerife in the Canary Islands, where they took in supplies (including vegetable and pitch, which were cheaper to acquire there than in Spain).[49] During the stop, Magellan received a secret message from his brother-in-law, Diogo Barbosa, warning him that some of the Castilian captains were planning a mutiny, with Juan de Cartagena (captain of the San Antonio) being the ring-leader of the conspiracy.[50] He also learned that the King of Portugal had sent two fleets of caravels to arrest him.

On 3 October, the fleet departed the Canary Islands, sailing south along the coast of Africa. There was some disagreement over directions, with Cartagena arguing for a more westerly bearing.[51] Magellan made the unorthodox decision to follow the African coast in order to evade the Portuguese caravels which were pursuing him.[52]

Toward the end of October, as the Armada approached the equator, they experienced a series of storms, with such intense squalls that they were sometimes forced to strike their sails.[53] Pigafetta recorded the appearance of St. Elmo's fire during some of these storms, which was regarded as a good omen by the crew:

During these storms the body of St. Anselme appeared to us several times; amongst others, one night that it was very dark on account of the bad weather, the said saint appeared in the form of a fire lighted at the summit of the mainmast, and remained there near two hours and a half, which comforted us greatly, for we were in tears, only expecting the hour of perishing; and when that holy light was going away from us it gave out so great a brilliancy in the eyes of each, that we were near a quarter-of-an-hour like people blinded, and calling out for mercy. For without any doubt nobody hoped to escape from that storm.[54]

After two weeks of storms, the fleet spent some time stalled in calm, equatorial waters before being carried west by the South Equatorial Current to the vicinity of the trade winds.

Sodomy trial and failed mutiny

During the ocean crossing, the Victoria's Sicilian master, Salomon Antón was caught in an act of sodomy with a Genoese apprentice sailor, António Varesa, off the coast of Guinea.[55][56][54] At the time, sodomy was punishable by death in Spain, though in practice, sex between men was a common occurrence on long naval voyages.[57] Magellan held a trial on board the Trinidad and found Antón guilty, sentencing him to death by strangulation. Antón was later executed on 20 December 1519, after the fleet's landfall in Brazil at Santa Lucia (present-day Rio de Janeiro), his strangled body being burnt.[55][54] Varesa drowned after going overboard on 27 April 1520, having been thrown off by his shipmates.[58][55][59]

In a meeting following the trial, Magellan's captains challenged his leadership. Cartagena accused Magellan of risking the King's ships by his choice of route, sailing South along the African coast. When Cartagena declared that he would no longer follow Magellan's command, Magellan gave the signal for a number of armed loyalists to enter the room and take hold of Cartagena. Magellan called Cartagena a "rebel" and branded his behaviour as mutinous. Cartagena called on the other two Castilian captains (Quesada and Mendoza) to stab Magellan, but they held back.

Immediately following the episode, Cartagena was placed in stocks. Magellan could have tried Cartagena for mutiny and sentenced him to death, but at the urging of Quesada and Mendoza, he agreed to merely relieve Cartagena of his command of the San Antonio and allow him to move freely within the confines of the Victoria. Antonio de Coca replaced Cartagena as captain of the San Antonio.[60]

Some details about the sodomy trial and its aftermath are disputed. Salomon Antón's name is also given in some sources as Antonio Salamón, Antonio Salamone, and Antonio Salomón, with his job being alternatively listed as boatswain and quartermaster.[54][58][61] António Varesa's name is also given as Antonio Ginovés, with his job also being listed as cabin boy, "ship's boy", or "grummet".[58][61][55] Varesa's death is also sometimes described as a suicide from being ridiculed or that he too was outright sentenced to death during the trial.[54][62] The date of the trial is also given as September.[62]

Passage through South America

Arrival in Brazil

On 29 November, the fleet reached the approximate latitude of Cape Saint Augustine.[63] The coastline of Brazil (which Pigafetta refers to as Verzin in his diary, after the Italian term for brazilwood[64]) had been known to the Spanish and Portuguese since about 1500, and in the intervening decades, European powers (particularly Portugal) had been sending ships to Brazil to collect valuable brazilwood. The Armada carried a map of the Brazilian coastline, the Livro da Marinharia (the "Book of the Sea"), and also had a crew member, the Concepción's pilot, João Lopes Carvalho, who had previously visited Rio de Janeiro. Carvalho was enlisted to lead the fleet's navigation down the Brazilian coastline to Rio, aboard the Trinidad, and also helped communicate with the locals, as he had some rudimentary knowledge of their Guarani language.[65]

On 13 December, the fleet reached Rio de Janeiro. Though nominally Portuguese territory, they maintained no permanent settlement there at the time. Seeing no Portuguese ships in the harbour, Magellan knew it would be safe to stop.[66] Pigafetta wrote of a coincidence of weather that caused the armada to be warmly received by the indigenous people:

It is to be known that it happened that it had not rained for two months before we came there, and the day that we arrived it began to rain, on which account the people of the said place said that we came from heaven, and had brought the rain with us, which was great simplicity, and these people were easily converted to the Christian faith.[54]

The fleet spent 13 days in Rio, during which they repaired their ships, stocked up on water and food (such as yam, cassava, and pineapple), and interacted with the locals. The expedition had brought with them a great quantity of trinkets intended for trade, such as mirrors, combs, knives and bells. The locals readily exchanged food and local goods (such as parrot feathers) for such items. The crew also found they could purchase sexual favours from the local women. Historian Ian Cameron described the crew's time in Rio as "a saturnalia of feasting and lovemaking".[67]

On 27 December, the fleet left Rio de Janeiro. Pigafetta wrote that the natives were disappointed to see them leave, and that some followed them in canoes trying to entice them to stay.[68] Just before sailing, Magellan replaced Antonio de Coca, the fleet accountant who had briefly assumed command of San Antonio from Cartagena, with the inexperienced Álvaro de Mezquita who originally had shipped out aboard the flagship from Seville as a mere supernumerary.[69]

Río de la Plata

The fleet sailed south along the South American coast, hoping to reach el paso, the fabled strait that would allow them passage past South America to the Spice Islands. On 11 January[n 4], a headland marked by three hills was sighted, which the crew believed to be "Cape Santa Maria". Around the headland, they found a wide body of water that extended as far as the eye could see in a west-by-southwest direction. Magellan believed he had found el paso, though in fact he had reached the Río de la Plata. Magellan directed the Santiago, commanded by Juan Serrano, to probe the 'strait', and led the other ships south hoping to find Terra Australis, the southern continent which was then widely supposed to exist south of South America. They failed to find the southern continent, and when they regrouped with the Santiago a few days later, Serrano reported that the hoped-for strait was in fact the mouth of a river. Incredulous, Magellan led the fleet through the western waters again, taking frequent soundings. Serrano's claim was confirmed when the men eventually found themselves in fresh water.[68]

Search for strait

On 3 February, the fleet continued south along the South American coast.[70] Magellan believed they would find a strait (or the southern terminus of the continent) within a short distance.[71] In fact, the fleet would sail south for another eight weeks without finding passage, before stopping to overwinter at St. Julian.

Not wanting to miss the strait, the fleet sailed as close to the coast as feasible, heightening the danger of running aground on shoals. The ships sailed only during the day, with lookouts carefully watching the coast for signs of a passage. In addition to the hazards of shallow waters, the fleet encountered squalls, storms, and dropping temperatures as they continued south and winter set in.

Overwintering

By the third week of March, weather conditions had become so desperate that Magellan decided they should find a safe harbour in which to wait out the winter before resuming the search for a passage in spring. On 31 March 1520, a break in the coast was spotted. There, the fleet found a natural harbour which they called Port St. Julian.[72]

The men remained at St. Julian for five months, before resuming their search for the strait.

Easter mutiny

Within a day of landing at St. Julian, there was another mutiny attempt. Like the one during the Atlantic crossing, it was led by Juan de Cartagena (former captain of the San Antonio), aided by Gaspar de Quesada and Luis Mendoza, captains of the Concepción and Victoria, respectively. As before, the Castilian captains questioned Magellan's leadership and accused him of recklessly endangering the fleet's crew and ships.

The mutiny at St. Julian was more calculated than the fracas that had followed the sodomy trial during the Atlantic crossing. Around midnight of Easter Sunday, 1 April, Cartagena and Quesada covertly led thirty armed men, their faces covered with charcoal, aboard the San Antonio, where they ambushed Álvaro de Mezquita, the recently named captain of the ship. Mezquita was Magellan's cousin and sympathetic to the captain general. Juan de Elorriaga, the ship's master, resisted the mutineers and attempted to alert the other ships. For this reason, Quesada stabbed him repeatedly (he would die from his wounds months later).[73]

With the San Antonio subdued, the mutineers controlled three of the fleet's five ships. Only the Santiago (commanded by Juan Serrano) remained loyal to Magellan, along with the flag ship, the Trinidad, which Magellan commanded. The mutineers aimed the San Antonio's cannon at the Trinidad but made no further overtures during the night.

The following morning (2 April), while the mutineers attempted to consolidate their forces aboard the San Antonio and the Victoria, a longboat of sailors drifted off course into the vicinity of the Trinidad. The men were brought aboard and persuaded to divulge the details of the mutineers' plans to Magellan.

Magellan subsequently launched a counteroffensive against the mutineers aboard the Victoria. He had some marines from the Trinidad switch clothing with the stray sailors and approach the Victoria in their longboat. His alguacil, Gonzalo de Espinosa, also approached the Victoria in a skiff and announced that he had a message for the captain, Luis Mendoza. Espinosa was allowed aboard, and into the captain's chambers, based on his claim that he had a confidential letter. There, Espinosa stabbed Mendoza in the throat with his poignard, killing him instantly. At the same time, the disguised marines came aboard the Victoria to support the alguacil.[74]

With the Victoria lost and Mendoza dead, the remaining mutineers realised they were outmanoeuvred. Quesada attempted to flee but was prevented from doing so – sailors loyal to Magellan had cut the Concepción's cables, causing it to drift toward the Trinidad, and Quesada was captured. Cartagena conceded and begged Magellan for mercy.[75]

Mutiny trial

The trial of the mutineers was headed by Magellan's cousin Álvaro de Mezquita and lasted five days. On 7 April, Quesada was beheaded by his foster-brother and secretary, Luis Molina, who acted as executioner in exchange for clemency. The bodies of Quesada and Mendoza were drawn and quartered and displayed on gibbets for the following three months. San Martín, suspected of involvement in the conspiracy, was tortured by strappado, but afterwards was allowed to continue his service as cosmographer.[76] Cartagena, along with a priest, Pedro Sanchez de Reina, were sentenced to be marooned.[77] On 11 August, two weeks before the fleet left St. Julian, the two were taken to a small nearby island and left to die.[78] Days later, the pilot of the ship San Antonio, Esteban Gómez, shot down its captain, Álvaro de Mezquita, Magellan's cousin, abandoning Magellan's expedition to return to Spain. He returned for Juan de Cartagena and Pedro Sánchez de la Reina, but found no trace of them. More than forty[79] other conspirators, including Juan Sebastián Elcano,[80] were put in chains for much of the winter and made to perform the hard work of careening the ships, repairing their structure and scrubbing the bilge.[81]

Loss of Santiago

In late April, Magellan dispatched the Santiago, captained by Juan Serrano, from St. Julian to scout to the south for a strait. On 3 May, they reached the estuary of a river which Serrano named Santa Cruz River.[82] The estuary provided shelter and was well situated with natural resources including fish, penguins, and wood.[83]

After more than a week exploring Santa Cruz, Serrano set out to return to St. Julian on 22 May, but was caught in a sudden storm while leaving the harbour.[40][41] The Santiago was tossed about by strong winds and currents before running aground on a sandbar. All (or nearly all[n 5]) of the crew were able to clamber ashore before the ship capsized. Two men volunteered to set off on foot for St. Julian to get help. After 11 days of hard trekking, the men arrived at St. Julian, exhausted and emaciated. Magellan sent a rescue party of 24 men over land to Santa Cruz.

The other 35 survivors from the Santiago remained at Santa Cruz for two weeks. They were unable to retrieve any supplies from the wreck of the Santiago, but managed to build huts and fire, and subsist on a diet of shellfish and local vegetation. The rescue party found them all alive but exhausted, and they returned to St. Julian safely.[84]

Move to Santa Cruz

After learning of the favourable conditions that Serrano found at Santa Cruz, Magellan decided to move the fleet there for the rest of the austral winter. After almost five months at St. Julian, the fleet left for Santa Cruz around 24 August. They spent six weeks at Santa Cruz before resuming their search for the strait.[85]

Strait of Magellan

On 18 October, the fleet left Santa Cruz heading south, resuming their search for a passage. Soon after, on 21 October 1520, they spotted a headland at 52°S latitude which they named Cape Virgenes. Past the cape, they found a large bay. While they were exploring the bay, a storm erupted. The Trinidad and Victoria made it out to open seas, but the Concepción and San Antonio were driven deeper into the bay, toward a promontory. Three days later, the fleet was reunited, and the Concepción and San Antonio reported that the storm drew them through a narrow passage, not visible from sea, which continued for some distance. Hoping they had finally found their sought-after strait, the fleet retraced the path taken by the Concepción and San Antonio. Unlike at Río de la Plata earlier, the water did not lose its salinity as they progressed, and soundings indicated that the waters were consistently deep. This was the passage they sought, which would come to be known as the Strait of Magellan. At the time, Magellan referred to it as the Estrecho (Canal) de Todos los Santos ("All Saints' Channel") because the fleet travelled through it on 1 November or All Saints' Day.

On 28 October, the fleet reached an island in the strait (likely Isabel Island or Dawson Island), which could be passed in one of two directions. Magellan directed the fleet to split up to explore the respective paths. They were meant to regroup within a few days, but the San Antonio would never rejoin the fleet.[86] While the rest of the fleet waited for the return of the San Antonio, Gonzalo de Espinosa led a small ship to explore the further reaches of the strait. After three days of sailing, they reached the end of the strait and the mouth of the Pacific Ocean. After another three days, Espinosa returned. Pigafetta writes that, on hearing the news of Espinosa's discovery, Magellan wept tears of joy.[87] The fleet's remaining three ships completed the journey to the Pacific by 28 November after weeks of fruitlessly searching for the San Antonio.[88] Magellan named the waters the Mar Pacifico, or Pacific Ocean, because of how still and peaceful the sea was, especially compared with the straits.[89][7]

Desertion of San Antonio

The San Antonio failed to rejoin the rest of Magellan's fleet in the strait. At some point, they reversed course and sailed back to Spain. The ship's officers later testified that they had arrived early at the appointed rendezvous location, but it's not clear whether this is true.[90] The captain of the San Antonio at the time, Álvaro de Mezquita, was Magellan's cousin and loyal to the captain-general. He directed attempts to rejoin the fleet, firing cannons and setting off smoke signals. At some point he was overpowered in yet another mutiny attempt, this one successful. He was stabbed by the pilot of the San Antonio, Estêvão Gomes, and put in chains for the remainder of the journey.[91] Gomes was known to have feelings of animosity towards Magellan (as documented by Pigafetta, who wrote that "Gomes... hated the Captain General exceedingly", because he had hoped to have his own expedition to the Moluccas funded instead of Magellan's[92]), and shortly before the fleet was separated, had argued with him about their next course of action. While Magellan and the other officers agreed to continue west to the Moluccas, thinking that their 2–3 months of rations would be sufficient for the journey, Gomes argued that they should return to Spain the way they had come, to muster more supplies for another journey through the strait.[93]

The San Antonio reached Seville approximately six months later, on 6 (or 8[94]) May 1521, with 55 survivors. There ensued a trial of the ship's men which lasted six months. With Mezquita being the only one loyal to Magellan, the majority of testimony produced a villainous and distorted picture of Magellan's actions. In particular, in justifying the mutiny at St. Julian, the men claimed that Magellan had tortured Spanish seamen (during the return journey across the Atlantic, Mezquita was tortured into signing a statement to this effect) and claimed that they were merely trying to make Magellan follow the king's orders. Ultimately, none of the mutineers faced charges in Spain. Magellan's reputation suffered as a result, as did his friends and family. Mezquita was kept in jail for a year following the trial, and Magellan's wife, Beatriz, had her financial resources cut off and was placed under house arrest along with their son.[95]

Pacific crossing

Magellan (along with contemporary geographers) had no conception of the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. He imagined that South America was separated from the Spice Islands by a small sea, which he expected to cross in as little as three or four days.[96] In fact, they spent three months and twenty days at sea, before reaching Guam and then the Philippines.

The fleet entered the Pacific from the Strait of Magellan on 28 November 1520 and initially sailed north, following the coast of Chile. By mid-December, they altered their course to west-north-west.[97] They were unfortunate in that, had their course differed slightly, they might have encountered a number of Pacific islands which would have offered fresh food and water, such as the Marshall Islands, the Society Islands, the Solomon Islands or the Marquesas Islands. As it was, they encountered only two small uninhabited islands during the crossing, at which they were unable to land, the reason why they named them Islas Infortunadas. The first, sighted 24 January, they named San Pablo (Saint Paul in Spanish) – likely Puka-Puka.[98] The second, sighted 21 February, they named Tiburones (Sharks in Spanish) – likely Caroline Island[99] or Flint Island.[100] They crossed the equator on 13 February.

Not expecting such a long journey, the ships were not stocked with adequate food and water, and much of the seal meat they had stocked putrefied in the equatorial heat. Pigafetta described the desperate conditions in his journal:

we only ate old biscuit reduced to powder, and full of grubs, and stinking from the dirt which the rats had made on it when eating the good biscuit, and we drank water that was yellow and stinking. We also ate the ox hides which were under the main-yard, so that the yard should not break the rigging: they were very hard on account of the sun, rain, and wind, and we left them for four or five days in the sea, and then we put them a little on the embers, and so ate them; also the sawdust of wood, and rats which cost half-a-crown each, moreover enough of them were not to be got.[54]

Moreover, most of the men suffered from symptoms of scurvy, whose cause was not understood at the time. Pigafetta reported that, of the 166 men[101][102][need quotation to verify] who embarked on the Pacific crossing, 19 died and "twenty-five or thirty fell ill of diverse sicknesses".[54] Magellan, Pigafetta, and other officers were not afflicted with scorbutic symptoms, which may have been because they ate preserved quince which (unbeknownst to them) contained the vitamin C necessary to protect against scurvy.[103]

Guam and the Philippines

On 6 March 1521, the fleet reached the Mariana Islands. The first land they spotted was likely the island of Rota, but the ships were unable to land there. Instead, they dropped anchor thirty hours later on Guam, where they were met by native Chamorro people in proas, a type of outrigger canoe then unknown to Europeans. Dozens of Chamorros came aboard and began taking items from the ship, including rigging, knives, and any items made of iron. At some point, there was a physical confrontation between the crew and the natives, and at least one Chamorro was killed. The remaining natives fled with the goods they had obtained, also taking Magellan's bergantina (the ship's boat kept on the Trinidad) as they retreated.[104][105] For this act, Magellan called the island Isla de los Ladrones (Island of Thieves).[106]

The next day, Magellan retaliated, sending a raiding party ashore which looted and burned forty or fifty Chamorro houses and killed seven men.[107] They recovered the bergantina and left Guam the next day, 9 March, continuing westward.[108]

The Philippines

The fleet reached the Philippines on 16 March, and remained there until 1 May. The expedition represented the first documented European contact with the Philippines.[109] Although the stated goals of Magellan's expedition were to find a passage through South America to the Moluccas and return to Spain laden with spices, at this point in the journey, Magellan seemed to acquire a zeal for converting the local tribes to Christianity. In doing so, Magellan eventually became embroiled in a local political dispute, and died in the Philippines, along with dozens of other officers and crew.

On 16 March, a week after leaving Guam, the fleet first sighted the island of Samar, then landed on the island of Homonhon, which was then uninhabited. They encountered friendly locals from the nearby island of Suluan and traded supplies with them. They spent nearly two weeks on Homonhon, resting and gathering fresh food and water, before leaving on 27 March.[110] On the morning of 28 March, they neared the island of Limasawa and encountered some natives in canoes who then alerted balangay warships of two local rulers from Mindanao who were on a hunting expedition in Limasawa. For the first time on the journey, Magellan's slave Enrique of Malacca found that he was able to communicate with the natives in Malay (an indication that they had indeed completed a circumnavigation, and were approaching familiar lands).[110] They exchanged gifts with the natives (receiving porcelain jars painted with Chinese designs), and later that day, Magellan was introduced to their leaders, Rajah Kolambu[n 6] and Rajah Siawi. Afterwards, Magellan would become a "blood brother" to Kolambu, undergoing the local blood compact ritual with him.[111]

Magellan and his men noted that the Rajahs had golden body ornaments and served food on golden plates. They were told by the Rajahs that gold was plentiful in their homelands in Butuan and Calagan (Surigao), and found that the locals were eager to trade it for iron at par. While at Limasawa, Magellan gave some of the natives a demonstration of Spanish armour, weapons, and artillery, by which they were apparently impressed.[112]

First Mass

On Sunday, 31 March, Easter Day, Magellan and fifty of his men came ashore to Limasawa to participate in the first Catholic Mass in the Philippines, given by the armada's chaplain. Kolambu, his brother (who was also a local leader), and other islanders joined in the ceremony and expressed an interest in their religion. Following Mass, Magellan's men raised a cross on the highest hill on the island, and formally declared the island, and the entire archipelago of the Philippines (which he called the Islands of St Lazarus) as a possession of Spain.[113]

Cebu

On 2 April, Magellan held a conference to decide the fleet's next course of action. His officers urged him to head south-west for the Mollucas, but instead he decided to press further into the Philippines. On 3 April, the fleet sailed north-west from Limasawa towards the island of Cebu, which Magellan learned of from Kolambu. The fleet was guided to Cebu by some of Kolambu's men.[114] They sighted Cebu 6 April, and made landfall the next day. Cebu had regular contact with Chinese and Arab traders and normally required that visitors pay tribute in order to trade. Magellan convinced the island's leader, Rajah Humabon, to waive this requirement.

As he had in Limasawa, Magellan gave a demonstration of the fleet's arms in order to impress the locals. Again, he also preached Christianity to the natives, and on 14 April, Humabon and his family were baptised and given an image of the Holy Child (later known as Santo Niño de Cebu). In the coming days, other local chieftains were baptised, and in total, 2,200 locals from Cebu and other nearby islands were converted.[115]

When Magellan learned that a group on the island of Mactan, led by Lapu-Lapu, resisted Christian conversion, he ordered his men to burn their homes. When they continued to resist, Magellan informed his council on 26 April that he would bring an armed contingent to Mactan and make them submit under threat of force.[116]

Battle of Mactan

Magellan mustered a force of 60 armed men from his crew to oppose Lapu-Lapu's forces. Some Cebuano men followed Magellan to Mactan, but were instructed by Magellan not to join the fight, but merely to watch.[117] He first sent an envoy to Lapu-Lapu, offering him a last chance to accept the king of Spain as their ruler and avoid bloodshed. Lapu-Lapu refused. Magellan took 49 men to the shore while 11 remained to guard the boats. Though they had the benefit of relatively advanced armour and weaponry, Magellan's forces were greatly outnumbered. Pigafetta (who was present on the battlefield) estimated the enemy's number at 1,500.[118] Magellan's forces were driven back and decisively defeated. Magellan died in battle, along with several comrades, including Cristóvão Rebelo, Magellan's illegitimate son.[119]

1 May Massacre

Following Magellan's death, the remaining men held an election to select a new leader for the expedition. They selected two co-commanders: Duarte Barbosa, Magellan's brother-in-law, and Juan Serrano. Magellan's will called for the liberation of his slave, Enrique, but Barbosa and Serrano demanded that he continue his duties as an interpreter for them, and follow their orders. Enrique had some secret communication with Humabon which caused him to betray the Spaniards.[120]

On 1 May, Humabon invited the men ashore for a great feast. It was attended by around thirty men, mostly officers, including Serrano and Barbosa. Towards the end of the meal, armed Cebuanos entered the hall and murdered the Europeans. Twenty-seven men were killed. Juan Serrano, one of the newly elected co-commanders, was left alive and brought to the shore facing the Spanish ships. Serrano begged the men on board to pay a ransom to the Cebuanos. The Spanish ships left port, and Serrano was (presumably) killed. In his account, Pigafetta speculates that João Carvalho, who became first in command in the absence of Barbosa and Serrano, abandoned Serrano (his one-time friend) so that he could remain in command of the fleet.[121]

Moluccas

With just 115 surviving men, out of the 277 who had sailed from Seville, it was decided the fleet did not have enough men to continue operating three ships. On 2 May, the Concepción was emptied and set on fire.[121] With Carvalho as the new captain-general, the remaining two ships, the Trinidad and Victoria, spent the next six months meandering through Southeast Asia in search of the Moluccas. On the way, they stopped at several islands including Palawan and Brunei. During this time, they engaged in acts of piracy, including robbing a junk bound for China from the Moluccas.[122]

On 21 September, Carvalho was made to step down as captain-general. He was replaced by Martin Mendez, with Gonzalo de Espinosa and Juan Sebastián Elcano as captains of the Trinidad and Victoria, respectively.

Aganduru Moriz' account of the expedition[123] describes how Elcano's crew was attacked somewhere off the southeastern tip of Borneo by a Bruneian fleet commanded by one of the Luzones. Historians such as William Henry Scott and Luis Camara Dery assert that this commander of the Bruneian Fleet was actually the young prince Ache of Maynila (Manila) a grandson of the Bruneian sultan who would later become Maynila's Rajah Matanda.[123][124]

Elcano, however, was able to defeat and capture Ache.[123] According to Scott, Ache was eventually released after a ransom was paid.[125] Nevertheless, Ache left a Spanish speaking Moor in Elcano's crew to assist the ship on the way back to Spain, "a Moor who understood something of our Castilian language, who was called Pazeculan."[126] This knowledge of the Spanish language was scattered across the Indian Ocean and even into Southeast Asia after the Castilian conquest of the Emirate of Granada forced the Spanish speaking Granadan Muslims to migrate across the Muslim world even as far as Islamic Manila.[127]

The ships finally reached the Moluccas on 8 November, when they reached the island of Tidore. They were greeted by the island's leader, al-Mansur (known to the officers by the Spanish name Almanzor).[128] Almanzor was a friendly host to the men, and readily claimed loyalty to the king of Spain. A trading post was established in Tidore and the men set about purchasing massive quantities of cloves in exchange for goods such as cloth, knives, and glassware.[129]

Around 15 December, the ships attempted to set sail from Tidore, laden with cloves. But the Trinidad, which had fallen into disrepair, was found to be taking on water. The departure was postponed while the men, aided by the locals, attempted to find and repair the leak. When these attempts were unsuccessful, it was decided that the Victoria would leave for Spain via a western route, and that the Trinidad would remain behind for some time to be refitted, before heading back to Spain by an eastern route, involving an overland passage across the American continent in the area of the Isthmus of Panama.[130] Several weeks later, Trinidad departed and attempted to return to Spain via the Pacific route. This attempt failed. Trinidad was captured by the Portuguese, and was eventually wrecked in a storm while at anchor under Portuguese control.[131]

Return to Spain

The Victoria set sail via the Indian Ocean route home on 21 December 1521, commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano. By 6 May 1522 the Victoria rounded the Cape of Good Hope, with only rice for rations. Twenty crewmen died of starvation by 9 July 1522, when Elcano put into Portuguese Cape Verde for provisions. The crew was surprised to learn that the date was actually 10 July 1522,[132] a day after their own meticulous records indicated. They had no trouble making purchases at first, using the cover story that they were returning to Spain from the Americas. However, the Portuguese detained 13 crew members after discovering that Victoria was carrying spices from the East Indies.[61][133] The Victoria managed to escape with its cargo of 26 tons of spices (cloves and cinnamon).

On 6 September 1522, Elcano and the remaining crew of Magellan's voyage arrived in Sanlúcar de Barrameda in Spain aboard Victoria, almost exactly three years after they departed. They then sailed upriver to Seville, and from there overland to Valladolid, where they appeared before the Emperor.

Survivors

When Victoria, the one surviving ship and the smallest carrack in the fleet, returned to the harbour of departure after completing the first circumnavigation of the Earth, only 18 men out of the original 270 men were on board. In addition to the returning Europeans, the Victoria had aboard three Moluccans who came aboard at Tidore.[134]

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Juan Sebastián Elcano | Getaria | Captain |

| Francisco Albo | Chios | Pilot |

| Miguel de Rodas | Rhodes | Shipmaster |

| Juan de Acurio | Bermeo | Boatswain |

| Martín de Judicibus | Savona | Sailor |

| Hernándo de Bustamante | Mérida | Barber |

| Antonio Pigafetta | Vicenza | Man-At-Arms |

| Maestre Anes (Hans)[136] | Aachen | Gunner |

| Diego Gallego | Bayona | Sailor |

| Antonio Hernández Colmenero | Huelva | Sailor |

| Nícolas de Napolés | Nafplio | Sailor |

| Francisco Rodríguez | Sevilla | Sailor |

| Juan Rodríguez de Huelva | Huelva | Sailor |

| Miguel de Rodas | Rhodes | Sailor |

| Juan de Arratía | Bilbao | Shipboy |

| Juan de Santander (Sant Andrés) | Cueto | Shipboy |

| Vasco Gómez Gallego | Bayona | Shipboy |

| Juan de Zubileta | Barakaldo | Page |

King Charles pressed for the release of the 12 men held captive by the Portuguese in Cape Verde, and they were eventually returned to Spain in small groups over the course of the following year.[137] They were:

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Martín Méndez | Sevilla | Scrivener |

| Pedro de Tolosa | Tolosa | Sailor |

| Richard de Normandía | Normandy, France | Carpenter |

| Roldán de Argote | Bruges | Gunner |

| Felipe de Rodas | Rhodes | Sailor |

| Gómez Hernández | Huelva | Sailor |

| Ocacio Alonso | Bollullos | Sailor |

| Pedro de Chindurza | Galvey | Shipboy |

| Vasquito Gallego | Bayona | Shipboy |

| Juan Martín | Bayona | Man-At-Arms |

| Pedro de Tenerife | Tenerife | Man-At-Arms |

| Simon de Burgos | Burgos | Man-At-Arms |

Between 1525 and 1526, the survivors of the Trinidad, who had been captured by the Portuguese in the Moluccas, were transported to a prison in Portugal and eventually released after a seven-month negotiation. Only five survived:[139]

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Ginés de Mafra | Jerez | Sailor |

| Leone Pancaldo | Genoa | Sailor |

| Hans Varga (Hans Barge [de])[n 7] | Germany | Constable |

| Juan Rodríguez "El Sordo" | Sevilla | Sailor |

| Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa | Burgos | Alguacil Mayor |

The following five nonsurvivors are considered to have successfully circumnavigated since they died after the Victoria and Trinidad had crossed the tracks of the outbound fleet.[139]

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Diego Garcia de Trigueros | Huelva | Sailor |

| Pedro de Valpuesta | Burgos | Man-At-Arms |

| Martín de Magallanes | Lisbon | Man-At-Arms |

| Estevan Villon | Trosic, Brittany | Sailor |

| Andrés Blanco | Tenerife | Shipboy |

Accounts of voyage

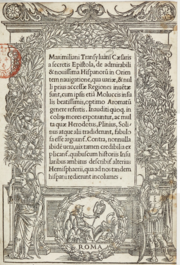

Antonio Pigafetta's journal, later published as Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, is the main primary source for much of what is known about Magellan's expedition.[141] The first published report of the circumnavigation was a letter written by Maximilianus Transylvanus, a relative of sponsor Cristóbal de Haro, who interviewed survivors in 1522 and published his account in 1523 under the title De Moluccis Insulis....[140][142] Initially published in Latin, other editions later appeared in Italian, Spanish, and English.[140]

In addition, there is an extant chronicle from Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, which was written in Spanish in 1522 or 1523, misplaced, then published again in 1530.[143]

Another reliable secondary source is the 1601 chronicle and the longer 1615 version, both by Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Herrera's account is all the more accurate as he had access to Spanish and Portuguese sources that are nowhere to be found today, not least Andrés de San Martín's navigational notes and papers. San Martin, the chief pilot-cosmographer (astronomer) of the Armada, disappeared in the Cebu massacre on 1 May 1521.[144][145]

In addition to Pigafetta's surviving journal, 11 other crew members kept written accounts of the voyage:

- Francisco Albo: the Victoria's pilot logbook ("Diario ó derrotero"), first referred to in 1788, and first published in its entirety in 1837[146][147] and a deposition on 18 October 1522[148]

- Martín de Ayamonte: a short account first published in 1933[149][150]

- Giovanni Battista: two letters dating from the 21 December 1521[151] and 25 October 1525[152][153] respectively

- Hernando de Bustamante: a deposition on 18 October 1522[148][154]

- Juan Sebastián Elcano: a letter written on 6 September 1522[155] and a deposition on 18 October 1522[148][156]

- Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa: a letter written on 12 January 1525,[157] a statement on 2 August 1527[158] and a deposition from the 2nd to the 5 September 1527[159][160]

- Ginés de Mafra: a detailed account first published in 1920,[161] a statement on 2 August 1527[158] and a deposition from 2 to 5 September 1527[159][162]

- Martín Méndez : the Victoria's logbook[163][164]

- Leone Pancaldo: a long logbook 'by the Genoese pilot' (first published in 1826),[165] a letter written on 25 October 1525,[166] a statement on 2 August 1527[167] and a deposition from 2 to 5 September 1527[168][169]

- an anonymous Portuguese crew member: a long manuscript, first published in 1937, known as "the Leiden manuscript", possibly written by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa and, in all likelihood, a Trinidad crew member[170][160]

- and another anonymous Portuguese crew member: a very short account, first published in 1554, written by a Trinidad crew member[171]

Legacy

Subsequent expeditions

Since there was not a set limit to the east, in 1524 both Portugal and Spain had tried to find the exact location of the antimeridian of Tordesillas, which would divide the world into two equal hemispheres and to resolve the "Moluccas issue". A board met several times without reaching an agreement: the knowledge at that time was insufficient for an accurate calculation of longitude, and each gave the islands to their sovereign.

In 1525, soon after the return of Magellan's expedition, Charles V sent an expedition led by García Jofre de Loaísa to occupy the Moluccas, claiming that they were in his zone of the Treaty of Tordesillas. This expedition included the most notable Spanish navigators, including Juan Sebastián Elcano, who, along with many other sailors, died during the voyage and the young Andrés de Urdaneta. They had difficulty reaching the Moluccas, docking at Tidore. The Portuguese were already established in nearby Ternate and the two nations had nearly a decade of skirmishing over the possession, which was still occupied by indigenous people.[citation needed] An agreement was reached only with the Treaty of Zaragoza, signed in 1529 between Spain and Portugal. It assigned the Moluccas to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.

In 1565, Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the Manila-Acapulco route.

The course that Magellan charted was later followed by other navigators, such as Sir Francis Drake during his circumnavigation in 1578,[172] in the process discovering a different route around the tip of South America, the “Drake Passage.” In 1960, the route was retraced completely submerged (with minor variations in course) by USS Triton.

Scientific accomplishments

Magellan's expedition was the first to circumnavigate the globe and the first to navigate the strait in South America connecting the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. Magellan's name for the Pacific was adopted by other Europeans.

Magellan's crew observed several animals that were entirely new to European science, including a "camel without humps", which was probably a guanaco, whose range extends to Tierra del Fuego. The llama, vicuña and alpaca natural ranges were in the Andes mountains. A black "goose" that had to be skinned instead of plucked was a penguin.[citation needed]

The full extent of the globe was realised, since their voyage was 14,460 Spanish leagues[173] (60,440 km or 37,560 mi).[5] The global expedition showed the need for an International Date Line to be established. Upon arrival at Cape Verde, the crew was surprised to learn that the ship's date of 9 July 1522 was one day behind the local date of 10 July 1522, even though they had recorded every day of the three-year journey without omission. They lost one day because they travelled west during their circumnavigation of the globe, in the same direction as the apparent motion of the sun across the sky.[174] Although the Kurdish geographer Abu'l-Fida (1273–1331) had predicted that circumnavigators would accumulate a one-day offset,[175] Cardinal Gasparo Contarini was the first European to give a correct explanation of the discrepancy.[176]

Quincentenary

In 2017, Portugal submitted an application to UNESCO to honour the circumnavigation route; the proposal was for a World Heritage Site called "Route of Magellan".[177]

In 2019, there were a number of events to mark the 500th anniversary of the voyage including exhibitions in various Spanish cities.[178]

To commemorate the 500th anniversary of Magellan's arrival in the Philippines, the National Quincentennial Committee put up monuments to mark the points where the fleet anchored.[179][180]

See also

Notes

- ^ 18 men returned on 6 September 1522 aboard the Victoria. Another 12 who had been captured by the Portuguese in Cape Verde made their way back to Spain over the following year. A few other survivors who had been stranded in the Moluccas were returned years later as Portuguese prisoners.

- ^ Bergreen 2003 says that the Santiago was a caravel and the other four were carracks.[28] Joyner 1992 labels all five ships as carracks.[29]

- ^ Note that many English sources such as Joyner[32] provide these numbers calqued as "tons" without converting their values from the actual unit, the Biscayan tonel ("tun"). At the time of Magellan's voyage, this tonel was reckoned as 1.2 toneladas[33] or roughly 1.7 m³, 60.1 cu. ft., or 0.6 English shipping tons.

- ^ (Cameron 1974, p. 96) gives a date of 11 January for this, whereas (Bergreen 2003, p. 105) gives 10 January.

- ^ (Cameron 1974, p. 156) says that "all her crew except one were able to leap ashore". (Bergreen 2003, p. 157) says "all the men aboard ship survived".

- ^ Variously romanised in different sources as Kolambu, Colembu, Kulambu, Calambu etc.

- ^ A German (before 1500–1527), captured at Tidore 1522 and spent the rest of his life in Portuguese captivity, died in Portugal.

References

Citations

- ^ "Spice Islands (Moluccas): 250 Years of Maps (1521–1760)". library.princeton.edu. Princeton University Library. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ferdinand Magellan". library.princeton.edu. Princeton University Library. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Cartwright, Mark (16 June 2021). "Ferdinand Magellan". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 30 April 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Ferdinand Magellan – Early Years, Expedition & Legacy". History.com. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b Lavery, Brian (2013). The Conquest of the Ocean: An Illustrated History of Seafaring. New York, NY: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4654-1387-1.

Distance of Magellan's voyage: 37,560 miles (60,440 km)

- ^ Redondo, J.M.G., & Martín, J.M.M. (2021). Making a Global Image of the World: Science, Cosmography and Navigation in Times of the First Circumnavigation of Earth, 1492–1522. Spanish National Research Council. Culture & History Digital Journal. 10(2). ISSN 2253-797X

- ^ a b Seelye Jr., James E.; Selby, Shawn, eds. (2018). Shaping North America: From Exploration to the American Revolution. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 612. ISBN 9781440836695.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 211, 214.

- ^ Bergreen 2006.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 48.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 49.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 56: "While court chronicles do not state so clearly, he likely implored the king to allow him to take men, arms, and supplies to the Moluccas..."

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Joyner 1992, pp. 87, 296–298.

- ^ a b c d Beaglehole 1966, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Joyner 1992, pp. 87, 296.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 296.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 297.

- ^ Ehrenberg, Ralph E. (2002). "Marvellous countries and lands; Notable Maps of Florida, 1507–1846". Archived from the original on 12 March 2008.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 61, 331 footnote 2.

- ^ González, Fernando (2018). "Los barcos de la armada del Maluco" (PDF). Congreso Internacional de Historia 'Primus Circumdedisti Me'. Valladolid: Ministerio de Defensa. pp. 179–188. ISBN 978-84-9091-390-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Vial, Ignacio Fernandez (2001). La Primera Vuelta al Mundo: La Nao Victoria. Servilla: Munoz Moya Editores.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 170.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Joyner 1992, pp. 93, 245.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 74.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 94.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Walls y Merino 1899, Annex 3, p. 174.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 336.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 337.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 43.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 49, 337.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 338.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 339.

- ^ a b Joyner 1992, p. 146.

- ^ a b Bergreen 2003, p. 156.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 335.

- ^ Nancy Smiler Levinson (2001). Magellan and the First Voyage Around the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-395-98773-5. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

Personnel records are imprecise. The most accepted total number is 270.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 61.

- ^ a b Joyner 1992, p. 104.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 90.

- ^ Beaglehole 1966, p. 22.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 84.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 86.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pigafetta, Antonio. The First Voyage Round the World. Translated by Stanley, Henry. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Carvajal, Federico Garza (2010). Butterflies Will Burn: Prosecuting Sodomites in Early Modern Spain and Mexico. University of Texas Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-292-77994-5.

- ^ Reyes, Raquel A. G.; Clarence-Smith, William G. (2012). Sexual Diversity in Asia, c. 600–1950. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-29721-2.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c Kelsey 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 103.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Morison, Samuel Eliot (1986). The Great Explorers: The European Discovery of America. Oxford University Press. p. 667. ISBN 978-0-19-504222-1.

- ^ a b Giraldez, Arturo (2015). The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4422-4352-1.

- ^ "Log-Book of Francisco Alvo or Alvaro". The First Voyage Round the World. Translated by Stanley, Henry Edward John. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 97.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 95.

- ^ a b Cameron 1974, p. 96.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 123.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 97.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 115–117.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 170.

- ^ Hildebrand, Arthur Sturges (1925). Magellan. A general account of the life and times and remarkable adventures ... of ... Ferdinand Magellan, etc. [With a portrait.] London. OCLC 560368881.

- ^ Murphy, Patrick J.; Coye, Ray W. (2013). Mutiny and Its Bounty: Leadership Lessons from the Age of Discovery. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300170283. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 113.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 170–173.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 133.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 136.

- ^ "Ferdinand Magellan". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 191.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 187–188.

- ^ "Carta de los oficiales de la Casa de la Contratación de las Indias al emperador Carlos V, sobre regreso de la nao "San Antonio" y denuncias de sus mandos de los excesos de Fernando de Magallanes" (in Spanish). Consejo de Indias. 1521. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 297–312.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 145.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 149.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 159.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 218.

- ^ Maude, H. E. (1959). "Spanish discoveries in the Central Pacific". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 68 (4). Wellington, New Zealand: 291–293. JSTOR 20703766.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, p. 538.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 44.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 224–226.

- ^ Cameron 1974, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 226.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Suárez 1999, p. 138.

- ^ a b Cameron 1974, p. 173.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 243, 245.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 177.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 180.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 271.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 187.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 277.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 279.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 281.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 292.

- ^ a b Cameron 1974, p. 197.

- ^ Cameron 1974, p. 198.

- ^ a b c de Aganduru Moriz, Rodrigo (1882). Historia general de las Islas Occidentales a la Asia adyacentes, llamadas Philipinas. Colección de Documentos inéditos para la historia de España, v. 78–79. Madrid: Impr. de Miguel Ginesta.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 330.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ 'El libro que trajo la nao Vitoria de las amistades que hitieron con 10s Reyes de Maluco" (Archivo General de Indias, Indiferente General 1528), text in Mauricio Obregon, La primera vuelta al Mundo (Bogota, 1984), p. 300.

- ^ Damiao de Gois, Cronica do felicissimo rei de. Manuel (Lisboa, 1566), part 2, p. 113.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 341.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, pp. 363–365.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 381.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 386.

- ^ Koch, Peter O. (2015). To the Ends of the Earth: The Age of the European Explorers. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8380-8.

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 264.

- ^ Kelsey 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Lived ca. 1500–1545, also took part in the Loaisa-expedition of 1525, was saved by the Saavedra expedition and returned to Europe in 1534. He was the first human to circumvent the earth two times.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 406.

- ^ a b Kelsey 2016, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Kelsey 2016, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Joyner 1992, p. 349.

- ^ Bergreen 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 23, 71, 883–918, 1033–1034.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 71, 919–942, 1021.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 506, 945–1015.

- ^ Fitzpatrick & Callaghan 2008, pp. 149–150, 159.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 659 & 660–696.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 300.

- ^ a b c Castro et al. 2010, pp. 618–630.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 603–612.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 302.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 599–601.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 841–845.

- ^ Castro 2018, p. 303.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 613–616.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 837–840.

- ^ a b Castro et al. 2010, pp. 845–858.

- ^ a b Castro et al. 2010, pp. 859–880.

- ^ a b Castro 2018, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 697–732.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 631–657.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 733–755.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 841–858.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 859–861.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 861–880.

- ^ Castro 2018, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 757–782.

- ^ Castro et al. 2010, pp. 783–787.

- ^ Wagner, Henry R. (1926). Sir Francis Drake's Voyage Around the World: Its Aims and Achievements. San Francisco: John Howell.

- ^ "Ferdinand Magellan". library.princeton.edu. Princeton University Library. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

Victoria...tied up at the docks in the Triana district of Seville...after...a distance, according to [Antonio] Pigafetta, of 14,460 leagues

- ^ "Maps of the Magellan Strait and a brief history of Ferdinand Magellan". London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2006.

- ^ Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2018). Overcoming Ptolemy: The Revelation of an Asian World Region. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781498590143.

- ^ Winfree, Arthur T. (2001). The Geometry of Biological Time (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4757-3484-3.

- ^ "Route of Magellan". Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (20 September 2019). "Who First Circled the Globe? Not Magellan, Spain Wants You to Know". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ "PH to mark 'Filipino-centric' circumnavigation quincentennial". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Quincentennial marker unveiled in Homonhon Island". CNN Philippines. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

Bibliography

English

- Beaglehole, J.C. (1966). The Exploration of the Pacific (3rd ed.). London: Adam & Charles Black. OCLC 253002380.

- Bergreen, Laurence (2003). Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-093638-9.

- Bergreen, Laurence (2006). Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe (audio book). Blackstone Audio. ISBN 978-0-7927-4395-8. OCLC 1011550094.

- Cameron, Ian (1974). Magellan and the first circumnavigation of the world. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 029776568X. OCLC 842695.

- Cunnigham, Robert Oliver (1871). Notes on the natural history of the Strait of Magellan and west coast of Patagonia made during the voyage of H.M.S. Nassau in the years 1866, 67, 68, & 69. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas.

- Fitzpatrick, Scott M.; Callaghan, Richard (September 2008). "Magellan's Crossing of the Pacific". The Journal of Pacific History. 43 (2): 145–165. doi:10.1080/00223340802303611. S2CID 161223057.

- Joyner, Tim (1992). Magellan. International Marine. OCLC 25049890.

- Kelsey, Harry (2016). The First Circumnavigators: Unsung Heroes of the Age of Discovery. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22086-5. OCLC 950613571.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2022). East by West, The New Navigation of Ferdinand Magellan. Kew (Vic): Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 9781922669407. OCLC 1338665936.

- Salonia, Matteo (2022). "Encompassing the Earth: Magellan's Voyage from Its Political Context to Its Expansion of Knowledge". International Journal of Maritime History. 34 (4): 543–560. doi:10.1177/08438714221123468. S2CID 252451072.

- Suárez, Thomas (1999). Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions (HK). ISBN 9789625934709.

- Torodash, Martin (1971). "Magellan Historiography". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 51 (2): 313–335. doi:10.2307/2512478. JSTOR 2512478. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

French

- Castro, Xavier de; Hamon, Jocelyne; Thomaz, Luiz Filipe (2010). Le voyage de Magellan (1519–1522). La relation d'Antonio Pigafetta et autres témoignages (in French). Paris: Éditions Chandeigne, collection " Magellane ". ISBN 978-2915540-57-4.

- Castro, Xavier (2018). Le Voyage de Magellan : la relation d'Antonio Pigafetta du premier voyage autour du monde (in French). Paris: Éditions Chandeigne, collection " Magellane poche". ISBN 978-2-36732-125-7.

- Couto, Dejanirah (2013). Autour du Globe? La carte Hazine n°1825 de la bibliothèque du Palais de Topkapi, Istanbul (PDF) (in French). CFC, volume 216. pp. 119–134. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2019.

- Castro, Xavier de; Duviols, Jean-Paul (2019). Idées reçues sur les Grandes Découvertes: XVe-XVIe siècles (2e éd.) (in French). Paris: Éditions Chandeigne, collection "Magellane poche". ISBN 978-236732-188-2.

- Heers, Jacques (1991). La découverte de l'Amérique: 1492 (in French). Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe. ISBN 9782870274088.

Portuguese

- Garcia, José Manuel (2007). A Viagem de Fernão de Magalhães e os Portugueses (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Presença. ISBN 978-9722337519.

- Garcia, José Manuel (2019). Fernão e Magalhães – Herói, Traidor ou Mito: a História do Primeiro Homem a Abraçar o Mundo (in Portuguese). Manuscrito: Queluz de Baixo. ISBN 9789898975256., José Manuel García. International Congress of History Primus Circumdedisti Me. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020.

- Mota, Alvelino Teixeira da (1975). A viagem de Fernão de Magalhães e a questão das Molucas. Actas do II° colóquio luso-espahnol de História ultramarina (in Portuguese). Lisboa, Junta de Investigação Ultramarina-Centro de Cartografia Antiga. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022.

- Thomaz, Luís Filipe (2018). O drama de Magalhães e a volta ao mundo sem querer (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Gradiva. ISBN 9789896168599.

Spanish

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de (2002). Histoire des Indes (in French). Paris : Seuil. Historia de las Indias (vol. 3 de 5) - Bartolomé De Las Casas (in Spanish)

- Toribio Medina, José (1888–1902). Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de Chile : desde el viaje de Magallanes hasta la batalla de Maipo : 1518–1818 (in Spanish). Santiago: Imprenta Ercilla. ISBN 9781390781601. Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de Chile: desde el viaje de Magallanes hasta la batalla de Maipo: 1518–1818: tomo 7 – Memoria Chilena Archived 19 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Walls y Merino, ed. (1899). Primer Viaje Alrededor del Mundo... (PDF) (in Spanish). Translated by Carlos Amoretti. Madrid: n/a. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

External links

Media related to Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation at Wikimedia Commons- (in Spanish) Primera vuelta al mundo Magallanes-Elcano. V Centenario Archived 9 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Official site for the 5th centenary of the expedition.