First and second battles of Wonju

| First and Second Battles of Wonju | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean War | |||||||

US 2nd Infantry Division move through a mountain pass at the south of Wonju | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

US: 79,736[7][nb 2] South Korea: Unknown | ~61,500[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ~18,000 (estimated)[8] | ||||||

The First and Second Battles of Wonju (French: Bataille de Wonju), also known as the Wonju Campaign or the Third Phase Campaign Eastern Sector[nb 4] (Chinese: 第三次战役东线; pinyin: Dì Sān Cì Zhàn Yì Dōng Xiàn), was a series of engagements between North Korean and United Nations (UN) forces during the Korean War. The battle took place from December 31, 1950, to January 20, 1951, around the South Korean town of Wonju. In coordination with the Chinese capture of Seoul on the western front, the North Korean Korean People's Army (KPA) attempted to capture Wonju in an effort to destabilize the UN defenses along the central and the eastern fronts.

After a joint Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) and KPA assault breached the UN defenses at Chuncheon on New Year's Eve of 1951, KPA V Corps attacked US X Corps at Wonju while KPA II Corps harassed US X Corps' rear by engaging in guerrilla warfare. In response, US X Corps under the command of Major General Edward Almond managed to cripple the KPA forces at Wonju, and the UN forces later carried out a number of anti-guerrilla operations against the KPA infiltrators. In the aftermath of the battle, the KPA forces on the central and the eastern fronts were decimated, allowing the UN front to be stabilized at the 37th parallel.

Background

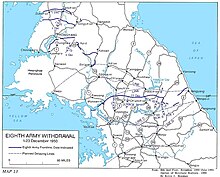

After launching a surprise invasion of South Korea in June 1950, the KPA was shattered by the United Nations (UN) forces following the landing at Incheon and the UN September 1950 counteroffensive, with the remnants of the KPA fleeing northward while seeking sanctuaries in the mountainous region along the Sino-Korean border.[10][11] The destruction of the KPA and the UN offensive into North Korea prompted China to intervene in the Korean War, and Chinese forces launched their Second Phase Offensive against the UN forces near the border during November 1950.[12] The resulting battles in the Ch'ongch'on River valley and at Chosin Reservoir forced the UN forces to retreat from North Korea during December 1950 to a line north of the 38th Parallel.[13] On the eastern front, US X Corps had evacuated North Korea by sea by December 24, 1950.[14] In its absence, the Republic of Korea Army (ROK) was forced to take over the defenses of the central and the eastern fronts along the 38th Parallel,[15] including the important road junction of Wonju located near the central front.[16] The sudden defeat of the UN forces offered the decimated KPA a brief respite, and they rebuilt their strength at the end of 1950.[11]

In the aftermath of the Chinese successes, Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong immediately ordered another offensive against the UN forces on the urging of North Korean Premier Kim Il Sung.[17] The offensive, dubbed the "Third Phase Campaign", was a border intrusion into South Korea that envisioned the total destruction of South Korean forces along the 38th parallel,[18] and was aimed at pressuring the UN forces to withdraw from the Korean Peninsula.[19] The western sector of the offensive was under the control of the PVA 13th Army,[18][nb 1] and the 13th Army's action would later result in capture of Seoul on January 4.[20] With the PVA 9th Army decimated at the Chosin Reservoir, however, the eastern sector of the offensive was handed over to the rehabilitated KPA, under the overall command of Lieutenant General Kim Ung and Commissar Pak Il-u.[21] On December 23, 1950, General Walton Walker, commander of the US Eighth Army, died in a traffic accident, and Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway assumed command of the Eighth Army on December 26, 1950.[22]

Prelude

Locations, terrain and weather

The battle's main focus was around a road dubbed "Route 29", a strategically important line of communication to the UN forces in central Korea. Wonju was a critical crossroad village on Route 29 which ran north to south and connects Chuncheon on the 38th Parallel with Daegu.[16][23] Another road, which ran from the northwest, connected Route 29 and Seoul at Wonju.[16] Between Chuncheon and Wonju stood the town of Hoengseong, and from Wonju to Daegu were a series of towns such as Chechon, Tanyang, Punggi and Andong.[16][24][25] The entire road network was situated within the rough hilly terrains of the Taebaek Mountain Range.[26] The fighting around Wonju occurred during some of the worst Korean winter conditions, with temperatures as low as −30 °F (−34 °C) and snow as thick as 14 in (36 cm) on the ground.[2] Indeed, the weather was so cold that metal on artillery pieces would crack, while water could take an hour-and-a-half to boil.[27] At times the cold weather alone was enough to stall all military activities, while frostbite caused more casualties than combat during the course of the battle.[2]

Forces and strategy

Just days before his death, Walker had tried to bolster the defences of the central and eastern sections of the 38th Parallel by stretching the ROK forces from Chuncheon to the Korean east coast.[15] Following his instructions, ROK III Corps was placed around Chuncheon while ROK I Corps was deployed on the east coast.[15] Meanwhile, ROK II Corps, with its strength reduced to a single infantry division in the aftermath of the Ch'ongch'on River battle,[28] filled the gap between ROK I and III Corps.[15] However, with the absence of US X Corps, the UN defenses on the central and eastern fronts were stretched thin, and there were gaps between the understrength ROK units.[15][29] Because the ROK forces had suffered nearly 45,000 casualties by the end of 1950,[30] most of their units were composed of raw recruits with little training,[31] and out of the four ROK divisions that defended Chuncheon, only one was deemed battle worthy.[32] Taking advantage of the situation, the KPA forces had been probing the ROK lines since mid-December, while thousands of North Korean guerrillas harassed the UN rear area from their mountain hideouts.[33] On December 27, 1950, KPA II Corps managed to move behind the UN defenses by mauling the ROK 9th Infantry Division on ROK I Corps' left flank at Hyon-ri. This development threatened to destabilize the entire UN eastern front.[34][35]

In order to defend against the KPA penetration, Ridgway ordered US X Corps to reinforce the ROK defenses.[26] However, with most of US X Corps still assembling at Pusan, the only unit that was available in the Eighth Army's reserve was the US 2nd Infantry Division, which was still recovering from its earlier losses at the Ch'ongch'on River.[32] On December 28, Ridgway ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to defend Wonju while placing the division under US X Corps control.[36] After the US 7th Infantry Division of US X Corps finished reorganization on December 30, Ridgway ordered Major General Edward Almond, commander of the US X Corps, to develop Route 29 as its main supply route, and the 7th Infantry Division was subsequently tasked with defending it.[37]

In coordination with the Chinese assaults against Seoul in the western sector of the Third Phase Campaign, the North Koreans deployed the KPA II, III and V Corps, an estimated 61,500 soldiers, against the UN forces on the central front.[24][38] The KPA plan was a frontal attack at Wonju by Major General Pang Ho San's KPA V Corps, while Major General Ch'oe Hyon's KPA II Corps would infiltrate the US X Corps' rear as guerrillas and block Route 29.[16][23] The aim of the offensive was to push US X Corps back in concert with the PVA attacks on Seoul, thereby isolating the ROK forces in the Taebaek Mountains.[24][39] As part of the attacks against Seoul, the PVA 42nd and 66th Corps were deployed near Chuncheon in support of KPA V Corps during the opening phase of the battle.[18] Meanwhile, KPA III Corps would act as reinforcements for KPA II and V Corps.[16] However, like the ROK they were facing, the KPA forces were also badly depleted and understrength.[16] Although the KPA fielded more than 10 infantry divisions for the battle,[39] most were only equivalent in strength to an infantry regiment.[16] In contrast with the professional mechanized army that had existed at the start of the Korean War, the newly rebuilt KPA formations were poorly trained and armed.[40] Nevertheless, the start date of the Third Phase Campaign was set for New Year's Eve in order to take advantage of the full moon and the low alertness of the UN soldiers during the holiday.[18]

First Battle of Wonju

Opening moves

On the central front, ROK III Corps defended the 38th parallel north of Gapyeong (Kapyong) and Chuncheon.[41] Composed of the ROK 2nd, 5th, 7th and 8th Infantry Divisions, ROK III Corps placed the ROK 2nd Infantry Division on the corps' left flank in the hills north of Gapyeong, while the ROK 5th Infantry Division defended the corps' center at Chuncheon.[41] The winter conditions created great difficulties for the South Korean defenders, with the heavy snow hindering construction and icy roads limiting food and ammunition resupply.[41] North Korean guerrillas were also active in the region, and caused serious disruption in the rear of the ROK III Corps.[41]

As part of the Chinese plan to capture Seoul, the PVA 42nd and the 66th Corps were tasked with protecting the PVA left flank by eliminating the ROK 2nd and 5th Infantry Divisions,[42] while cutting the road between Chuncheon and Seoul.[18] Following instructions, the two Chinese corps struck quickly after midnight on New Year's Eve.[43] The PVA 124th Division first penetrated the flanks of the ROK 2nd Infantry Division, then blocked the division's withdrawal route.[43][44] The trapped ROK 17th and 32nd Regiments, 2nd Infantry Division were then forced to retreat in disarray.[43] With the PVA 66th Corps pressuring the ROK 5th Infantry Division's front, the PVA 124th Division then advanced eastward in the rear and blocked the ROK 5th Infantry Division's retreat route as well.[44] The maneuver soon left the ROK 36th Regiment, 5th Infantry Division surrounded by PVA and they had to escape by infiltrating the PVA lines using mountain trails.[45] By January 1, ROK III Corps was in full retreat, while the Corps' headquarters had lost contact with the 2nd and 5th Infantry Divisions.[46] Responding to the crisis on the central front, ROK III Corps sector's defense was handed over to US X Corps.[46]

While the PVA were making a concentrated attack against the ROK front, the KPA forces that had infiltrated the UN rear were cutting the ROK withdrawal route.[47] In the days before the Chinese Third Phase Campaign, KPA II Corps established a major roadblock to the north of Hoengsong with an estimated strength of 10,000 soldiers, which blocked the retreat of ROK III Corps.[41][48] In response, ROK II Corps and the US 2nd Infantry Division conducted a siege operation against the roadblock from both the north and the south, and the roadblock was forced open by January 2.[49][50] Although the UN forces managed to eliminate a KPA division at the roadblock, ROK II Corps was nearly destroyed during the fighting, and it was disbanded on January 10.[51]

The success of the initial PVA/KPA attacks forced ROK I Corps to abandon its attempts to restore its original defensive position at Hyon-ri,[49] and a large number of KPA soon streamed into the gap between the US 2nd Infantry Division at Wonju and ROK I Corps on the east coast.[46] Ridgway interpreted the attack on the central front as an attempt to surround the UN defenders at Seoul, and he immediately ordered their evacuation on January 3.[52][53] On January 5, Ridgway ordered all UN forces to withdraw to the 37th parallel to set up a new defensive line, dubbed Line D, with the UN forces on central and eastern fronts setting up defenses between Wonju and the coastal city of Jumunjin (Chumunjin).[52][54] At the same time, the PVA troops halted their offensive operations with KPA II and V Corps relieving the PVA 42nd and 66th Corps.[20][55]

Wonju falls

In the aftermath of the ROK collapse, KPA V Corps proceeded to launch frontal attacks against US X Corps while KPA II Corps infiltrated the UN rear through the area to the east of Wonju.[56] The US 2nd Infantry Division's position had now become an exposed northern salient,[57] and its defenses were further hampered by the flat terrain surrounding Wonju.[58] However, given the strategic importance of Wonju in controlling central Korea,[16] Ridgway declared that the village was "only second to Seoul" in importance, and therefore must be defended at all cost.[57] In accordance with Ridgway's instructions, Almond ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to defend the hills north of Wonju, yet Division commander Major General Robert B. McClure believed that the salient was untenable due to the terrain and the low morale of his division.[59] On January 7, two infantry battalions from KPA V Corps launched an attack against the US 2nd Infantry Division.[60] One KPA battalion managed to infiltrate the American positions disguised as refugees while another battalion launched a frontal assault.[60][61] Yet the weak attack was soon repulsed due to the lack of coordination between the KPA units, and about 114 infiltrators were later captured.[62][63] Although the KPA attack inflicted little damage, the disruption caused by infiltrators in US 2nd Infantry Division's rear convinced McClure to abandon Wonju on January 7.[60] Almond concurred with McClure's decision on the condition that the US 2nd Infantry Division would only retreat 3 miles (4.8 km) so that Wonju could be controlled by UN artillery fire.[64] Regardless, McClure ordered the division to retreat more than 8 miles (13 km) south, putting the village out of artillery range.[65] With Wonju under KPA control, the PVA declared that the Third Phase Campaign had reached a successful conclusion.[66]

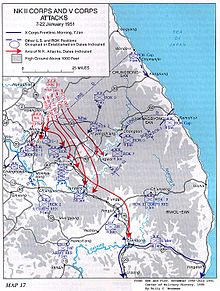

Second Battle of Wonju

Hill 247

Hill 247 was located among the hill mass 3 mi (4.8 km) south of Wonju,[65] and was a critical height that commanded Wonju.[67] With the loss of Wonju on January 7, Almond was furious at McClure for disobeying the order to hold it, and this later resulted in Major General Clark Ruffner replacing McClure on January 13.[68][69] On January 8, Almond ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to retake Wonju.[65] Following his orders, the US 23rd Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Paul L. Freeman, attacked towards Wonju on January 8.[70] The 23rd Infantry Regiment managed to reach within 3,000 yd (2,700 m) at the south of Wonju and caught a sleeping KPA regiment by surprise at Hill 247.[70] About 200 KPA soldiers were killed in the ensuing battle, however the alerted KPA forces soon counterattacked by outflanking the 23rd Infantry Regiment to the east, and the Regiment was forced to retreat to avoid encirclement.[70]

Encouraged by the heavy KPA losses during the initial UN attacks, Almond again ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to recapture Wonju on January 9.[71] About four infantry battalions from the US 23rd and 38th Infantry Regiments supported by French and Dutch troops advanced toward Wonju on January 9, yet the attack was stalled at Hill 247 due to the cold weather and the lack of air support.[67][70] As the UN forces tried to dislodge the KPA the next day, they were met by six defending KPA battalions with an estimated strength of 7,000 soldiers.[72] Under a heavy snowstorm and with no air support,[71] the battle for Hill 247 continued for most of January 10, and the fighting around the French Battalion of the 23rd Infantry Regiment became particularly fierce.[72] At one point, the French Battalion was forced to fend off several KPA counterattacks with bayonet charges after running out of ammunition.[5] The French Battalion's action at Wonju impressed Ridgway, who later encouraged all American units in Korea to utilize bayonets in battle.[5] The KPA tried to encircle the attacking UN forces as the latter began to gain the upper hand, however artillery fire broke up the KPA formations, and they had suffered an estimated 2,000 casualties in the aftermath of the battle.[5] When air support returned on January 11,[73] the attacking UN forces inflicted another 1,100 KPA casualties and captured Hill 247 by January 12.[2] Although the cold weather and the stubborn KPA defenses prevented the UN forces from entering Wonju, the capture of Hill 247 had put all of Wonju within UN artillery range, and the village soon became a no man's land under the devastating bombardment.[74]

Anti-guerrilla operations

Although the capture of Hill 247 had forced KPA V Corps to abandon Wonju with heavy losses on January 17,[40][75] KPA II Corps' infiltration in the UN rear area had become so serious that it threatened to outflank the entire UN front and force a complete evacuation of Korea by mid-January.[76][77] With the bulk of US X Corps tied up to the south of Wonju while ROK III Corps was in disarray, the front between Wonju and the east coast was undefended, and about 16,000 KPA soldiers entered the gap while establishing guerrilla bases from Tanyang to Andong.[78] The battles along the central front soon degenerated into irregular warfare between company-sized UN patrols and KPA guerrilla bands.[79] In an effort to stabilize the front, Ridgway ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to withdraw from Wonju while pulling the central and eastern fronts back to the area between Wonju and Samch'ok, and this resulted in another 40 mi (64 km) retreat.[66][80] Ridgway also sent the US 187th Regimental Combat Team, the US 5th Cavalry Regiment, the US 1st Marine Division and the Greek Battalion to contain KPA guerrillas east of Route 29 and north of Andong and Yeongdeok.[81][82] About 30,000 American infantry were deployed to the central front by mid-January,[83] and the KPA guerrillas were blocked in a narrow salient along the hills at the east of Route 29.[84]

To eliminate the KPA threat in the UN rear, Almond ordered all X Corps units on Route 29 to launch aggressive patrols to destroy the KPA supply bases and guerrilla bands.[85] Specially trained irregular forces, such as X Corps' Special Action Group, also hunted KPA units by operating as guerrillas themselves.[84] The constant UN pressure slowly depleted the ammunition and the manpower of KPA II Corps,[76] while Major General Yu Jae-hung rallied ROK III Corps and sealed the gap between Wonju and the east coast by January 22.[86] On January 20, a patrol carried out by the US 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division managed to reoccupy Wonju without much resistance.[87] Lacking reinforcements and supplies, KPA II Corps was scattered by the end of January, and only 8,600 soldiers from KPA II Corps managed to survive and retreat back to North Korea.[88] The KPA 10th Division, vanguard of KPA II Corps, was also annihilated by US 1st Marine Division during the UN anti-guerrilla operations.[89][90]

Aftermath

By the end of January, KPA II Corps was decimated during its guerrilla operations, and its estimated strength was reduced from 16,000 to 8,000.[8] KPA V Corps' attempt to capture Wonju had also resulted in crippling casualties, and its estimated strength was reduced from 32,000 to 22,000 by the end of January.[8] In contrast, UN losses were relatively moderate during the same period.[91][nb 5] The defeat of the KPA enabled the UN forces to consolidate their positions along the Korean central and eastern front,[89] and the retreating US Eighth Army on the Korean western front could finally return to the offensive after its rear and eastern flank were secured.[92] As soon as US X Corps regained full control of the central front at the end of January, Ridgway ordered the US Eighth Army to launch Operation Thunderbolt against PVA/KPA forces on January 25, 1951.[92][93]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ a b In Chinese military nomenclature, the term "Army" (军) means Corps, while the term "Army Group" (集团军) means Army.

- ^ KATUSA numbers not included. See Appleman 1990, p. 40.

- ^ This is the total casualty number of the US 2nd and 7th Infantry Division and the US 187th Regimental Combat Team from January 1 to January 24, 1951. The US 1st Marine Division and the US 1st Cavalry Division casualty number appears to be light. See Ecker 2005, pp. 73–75.

- ^ The Western Sector is the Third Battle of Seoul.

- ^ Although the unit-by-unit casualty data provided by Ecker suggested the US casualty number was around 600, the extent of the South Korean losses is unknown due to the lack of records. See Appleman 1989, p. 403.

- Citations

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 302.

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1990, p. 123.

- ^ Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2006, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1990, p. 122.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 134.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1990, p. 99.

- ^ Ecker 2005, pp. 73–75.

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 271.

- ^ a b Appleman 1989, p. 368.

- ^ Millett, Allan R. (2009). "Korean War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2012-01-22. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 160.

- ^ Mossman 1990, pp. 104, 173.

- ^ a b c d e Mossman 1990, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Appleman 1990, p. 98.

- ^ Zhang 1995, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e Zhang 1995, p. 127.

- ^ Zhang 1995, p. 126.

- ^ a b Zhang 1995, p. 131.

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 382.

- ^ Appleman 1989, pp. 390, 397.

- ^ a b Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 383–384.

- ^ a b c Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 383.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 218.

- ^ a b Appleman 1990, p. 96.

- ^ a b Appleman 1990, p. 124.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 315.

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 372.

- ^ Appleman 1989, pp. 368–369.

- ^ a b Millett 2010, p. 383.

- ^ Appleman 1989, p. 366.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 27, 28.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 313–315.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 27, 96.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 186.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Millett 2010, p. 387.

- ^ a b Mossman 1990, p. 223.

- ^ a b c d e Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 360.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 174

- ^ a b c Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 361.

- ^ a b Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 361–362.

- ^ a b c Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 386–387.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 362.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 30.

- ^ a b Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 363.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 100.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 98, 146.

- ^ a b Millett 2010, p. 384.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 58.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 210.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 219.

- ^ a b Blair 1987, p. 611.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 113.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 100, 113.

- ^ a b c Appleman 1990, p. 107.

- ^ Mahoney 2001, p. 55.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 104, 106.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 220.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 110, 116.

- ^ a b c Appleman 1990, p. 116.

- ^ a b Appleman 1990, p. 132.

- ^ a b Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 391.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 116, 128.

- ^ Blair 1987, p. 612.

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1990, p. 117.

- ^ a b Mossman 1990, p. 221.

- ^ a b Appleman 1990, p. 121.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 222.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 392.

- ^ a b Mossman 1990, p. 226.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 129.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 393–394, 448.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 129, 134.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 217.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 120, 134.

- ^ Mossman 1990, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Blair 1987, p. 618.

- ^ a b Millett 2010, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 225.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 442, 447.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 136.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 448.

- ^ a b Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 449.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 228.

- ^ Ecker 2005, p. 73.

- ^ a b Appleman 1990, p. 138.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 242.

References

- Appleman, Roy (1989), Disaster in Korea: The Chinese Confront MacArthur, vol. 11, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University Military History Series, ISBN 978-1-60344-128-5

- Appleman, Roy (1990), Ridgway Duels for Korea, vol. 18, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University Military History Series, ISBN 0-89096-432-7

- Blair, Clay (1987), The Forgotten War, New York, NY: Times Books, ISBN 0-8129-1670-0

- Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001), Yang, Hee Wan; Lim, Won Hyok; Sims, Thomas Lee; Sims, Laura Marie; Kim, Chong Gu; Millett, Allan R. (eds.), The Korean War, vol. II, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7795-3

- Chinese Military Science Academy (2000), History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea (抗美援朝战争史) (in Chinese), vol. II, Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House, ISBN 7-80137-390-1

- Ecker, Richard E. (2005), Korean Battle Chronology: Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures and Medal of Honor Citations, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1980-6

- Mahoney, Kevin (2001), Formidable Enemies: The North Korean and Chinese Soldier in the Korean War, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, ISBN 978-0-89141-738-5

- Millett, Allan R. (2010), The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came From the North, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (2006), Descendants of Athene: A History of Greek Soldiers' Participation in the Korean War, Sejong City, South Korea: Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, archived from the original on 2014-08-26, retrieved 2014-08-22

- Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (2010), A History of Netherland Forces' Participation in the Korean War (PDF), Sejong City, South Korea: Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-26, retrieved 2014-08-22

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990), Ebb and Flow: November 1950 – July 1951, United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, ISBN 978-1-4102-2470-5, archived from the original on 2021-01-29, retrieved 2010-11-08

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995), Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950–1953, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0723-4

Further reading

- Bowers, William T. (2008). The Line: Combat in Korea, January – February 1951. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2508-4.