First Battle of Dernancourt

| First Battle of Dernancourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Michael (German spring offensive) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 550+ killed or wounded | ||||||

The First Battle of Dernancourt was fought on 28 March 1918 near Dernancourt in northern France during World War I. It involved a force of the German 2nd Army attacking elements of the VII Corps, which included British and Australian troops, and resulted in a complete defeat of the German assault.

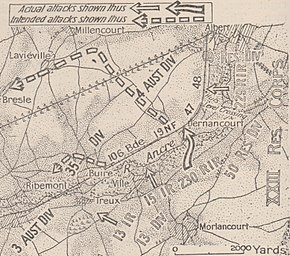

The Australian 3rd and 4th Divisions had been sent south from Belgium to help stem the tide of the German spring offensive towards Amiens and, with the British 35th Division, they held a line west and north of the Ancre river and the area between the Ancre and Somme, forming the southern flank of the Third Army. Much of the VII Corps front line consisted of a series of posts strung out along a railway embankment between Albert and Buire-sur-l'Ancre. The main German assault force was the 50th Reserve Division of the XXIII Reserve Corps, which concentrated its assault on the line between Albert and Dernancourt, attacking off the line of march after a short artillery preparation. Supporting attacks were to be launched by the 13th Division further west. Some German commanders considered success unlikely unless the embankment was weakly held, and the commander of the German 2nd Army ordered the attack to be postponed, but that message did not reach the assaulting troops in time.

The Germans attacked at dawn under the cover of fog, but other than one small penetration by a company in the early morning that was quickly repelled, partly due to the actions of Sergeant Stanley McDougall of the Australian 47th Battalion, the Germans failed to break through the VII Corps defences. McDougall was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award that could be received by an Australian soldier for gallantry in the face of the enemy. By late afternoon, rain set in, making early renewal of the assault less likely. The Germans suffered about 550 casualties during the battle, and the Australians lost at least 137 killed or wounded. The British 35th Division suffered 1,540 casualties from 25 to 30 March. In the week following the battle, the Germans renewed their attempts to advance in the sector, culminating in the Second Battle of Dernancourt on 5 April, when the Germans were defeated in desperate fighting.

Background

After the Third Battle of Ypres petered out in late 1917, the Western Front fell into its usual lull over the winter months. In early 1918, it became apparent to the Allies that a large German offensive was pending. This German spring offensive commenced on 21 March 1918, with over one million men in three German armies striking hard just north of the junction between the French and British armies. The main effort of this offensive hit the British Third and Fifth Armies, which formed the right flank of the British front line. Struck a series of staggering blows, a breach between the two British armies developed, and they were forced into a rapid, and in parts disorganised withdrawal, suffering heavy losses. The key railway junction at Amiens was soon threatened.[1][2]

Shortly after the Spring Offensive began, the Australian 3rd and 4th Divisions were deployed south in stages from rest areas in the Flanders region of Belgium to the Somme river valley in France to help stem the German offensive.[3] Initially it was intended to use them to launch a counter-offensive, but this idea was soon shelved due to German successes.[4] On their way south, the 4th Brigade was detached from the 4th Division to help halt the Germans near Hébuterne in the centre of the Third Army sector.[5] Travelling by train, bus and marching on foot, the remaining two brigades of the 4th Division, the 12th and 13th Brigades, concentrated in the area west of Dernancourt, under the command of the VII Corps led by Lieutenant General Walter Congreve, which now formed the right flank of the Third Army.[6][4]

The commander of the 4th Division, Major General Ewen Sinclair-Maclagan, was ordered to support and then relieve remnants of the 9th (Scottish) Division, which was holding the front line along a railway between Albert and Dernancourt, west of the Ancre river. This task was given to the 12th Brigade, under the command of Brigadier General John Gellibrand. The 13th Brigade was held in support positions between Bresle and Ribemont-sur-Ancre.[7] To the right of the 12th Brigade was the British 35th Division, positioned between Dernancourt and Buire-sur-l'Ancre, and commanded by Brigadier General Arthur Marindin.[a] That division had been involved in a series of fighting withdrawals since being committed to battle on 25 March near Cléry-sur-Somme, some 13 miles (21 km) east of Dernancourt. The 3rd Division, commanded by Major General John Monash, was deployed further to the south, between the Ancre and the Somme around Morlancourt, with its 10th Brigade to the right of the 35th Division.[9][10][11]

Preparations

VII Corps dispositions

From before midnight on 27 March, the now tired 12th Brigade had been holding the railway line between Albert and Dernancourt, having relieved the 9th (Scottish) Division.[13] The forward positions of the salient held by the 12th Brigade were along the railway line, which ran along a series of embankments and cuttings, up to but not including a railway bridge immediately northwest of Dernancourt where the Dernancourt–Laviéville road passed under the railway. Northwest of Dernancourt, a mushroom-shaped feature known as the Laviéville Heights overlooked the railway line, which curved around its foot. This was difficult ground to defend, particularly where the railway line curved and skirted the northwestern corner of Dernancourt, as the outskirts of the village were very close to the railway line at this point, and provided good concealment for approaching enemy troops. If the line there was overrun, the enemy would be able to fire into the rear of the troops deployed along the railway in both directions. Despite this, the Australian commanders considered it important to hold the railway line; if it was not garrisoned, the enemy could assemble in the dead ground behind the embankment. A further difficulty arose from the fact that if an attack occurred during daylight, it would be almost impossible to move troops down the exposed slopes to reinforce the railway line without crippling losses, and troops withdrawing from the railway line would be similarly exposed. To afford them some protection along the railway line, the forward posts dug one-man niches in the near side of the embankment, but the only way for them to fire was to climb up and lie on top of the embankment, thus exposing themselves to enemy fire.[14]

On the left of the brigade front, with its northern flank short of the Albert–Amiens road, was the 48th Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Leane. To its left was the British 12th (Eastern) Division of V Corps. The 48th Battalion was holding its sector with two companies in a series of posts along alternate cuttings and embankments of the railway line as it ran south from Albert. Close to that town the railway line was not in VII Corps hands, and the posts were thrown back along the side of a gully short of the Albert–Amiens road, in contact with the southern posts of the 12th (Eastern) Division, which extended south of the road at this point. The battalion frontage was about 1,300 yd (1,200 m). The 48th Battalion support line was located about 1,000 yd (910 m) to the rear on the high ground, astride the Albert–Amiens road. Due to the curvature of the slope, the two companies in the support line were out of sight of its forward companies at the railway line.[15][16]

On the right of the 48th Battalion was the 47th Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Imlay, with its two forward companies also strung out along the railway line. The total frontage of the 47th Battalion was 1,600 yd (1,500 m), which meant that the 180–200 men of the forward companies were positioned in widely spaced posts. Between the forward companies was a section of embankment near a level crossing which was not garrisoned, but was covered from a shallow cutting to the south and a low embankment to the north. The 47th Battalion's support line was also located on the hill some distance to the rear. The 12th Machine Gun Company was deployed with eight of its Vickers machine guns in each battalion area, mainly sited along the railway line. Leane and Imlay had their headquarters co-located on the summit next to the Albert–Amiens road. Of the two remaining battalions of the 12th Brigade, the 45th Battalion was deployed on the slope behind the 106th Brigade of the 35th Division, and the 46th Battalion was held in reserve near the village of Millencourt.[15]

On the right of the 12th Brigade were elements of the 35th Division, the first of these was the 19th (Service) Battalion (2nd Tyneside Pioneers) of the Northumberland Fusiliers (19th NF), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel W. P. S. Foord. It was deployed near the railway arch on the northwestern outskirts of Dernancourt. The right-hand gun of the 12th Machine Gun Company was positioned with this unit, which was under the control of the 106th Brigade. To their right the 106th Brigade was deployed along the railway line as far as Buire-sur-l'Ancre, the front line there being held by the 17th (Service) Battalion, Royal Scots, and the 12th (Service) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry. This section of the railway ran along flat ground. On its right, the 104th Brigade line ran from Buire-sur-l'Ancre past Treux, its forward battalions being the 18th (Service) Battalion (2nd South East Lancashire) of the Lancashire Fusiliers, and the 19th (Service) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry. The 104th Brigade overlapped and sheltered the left flank of the 10th Brigade of the 3rd Division, which was deployed just east of Méricourt-l'Abbé.[15][17] The VII Corps positions had excellent observation of the surrounding countryside, but were tactically weak.[18]

A significant amount of artillery support was available to the defenders. The divisional artillery of the 4th Division, consisting of the 10th and 11th Australian Field Artillery (AFA) Brigades, were within range, as were the British 50th and 65th Royal Field Artillery (RFA) Brigades. The S.O.S. lines of the 10th AFA Brigade were on a copse south of Albert, 200–600 yd (180–550 m) ahead of the 48th Battalion and those of the 11th AFA Brigade were on the far side of Dernancourt.[c] The Australian batteries were in the open, as pits had not yet been dug for them due to their recent arrival.[20]

German plan of attack

The main German attack was to be made by the 50th Reserve Division of General der Infanterie Hugo von Kathen's XXIII Reserve Corps. The 50th Reserve Division was a Prussian division that had been involved in the Spring Offensive from the outset. It had a few days' rest before the advance was delayed by the British at Albert and Dernancourt and its morale was still high. The right prong of the attack would be made by the 229th Reserve Infantry Regiment (RIR) advancing through the 9th Reserve Division north of Dernancourt against the sector held by the 48th Battalion. The left prong would consist of the 230th RIR, advancing from the area of Morlancourt through Dernancourt against the 47th Battalion and 19th NF. In this sector, I Battalion of the 230th RIR (I/230 RIR) would cross the Ancre and seize Dernancourt, then III Battalion, 230 RIR (III/230 RIR) would assault the embankment. After the capture of the embankment, the assaulting troops would push northwest over the Albert–Amiens road, then advance west towards Amiens. II Battalion, 230 RIR (II/230 RIR) was to follow up the assault of III/230 RIR. Both regimental commanders considered that the plan could succeed only if the embankment was weakly held and made representations to their brigade commander, to no avail. The German artillery preparation was to last only 45 minutes.[21]

Further west, supporting attacks were to be launched by the 13th Division, with the 15th Infantry Regiment (IR) assaulting across the Ancre towards the front line held by the 106th Brigade between Dernancourt and Buire-sur-l'Ancre and then exploiting success by driving west towards the village of Ribemont-sur-Ancre. The 13th IR was to attack the 104th Brigade at Marrett Wood. The German artillery preparation was to start at 05:15 on 28 March, and the assault to begin at 06:00. During the night of 27/28 March, the commander of the German 2nd Army apparently came to the same conclusion as the regimental commanders of the 50th Reserve Division, as at 03:00 he ordered the attack to be delayed until noon, and later further postponed it, but the orders did not reach the divisions in time.[22]

Battle

During the night of 27/28 March, patrols of the 47th Battalion had observed German troops on the Albert–Dernancourt road, on the open flats just 250–300 yd (230–270 m) across the railway line, but the night passed without obvious signs of attack.[23][24] Early in the morning, the German artillery fell heavily on the support lines and rear area, but initially was very light along the railway line.[25] In the thick mist of early dawn, the commander of a small post of the 47th Battalion, stationed behind the embankment immediately north of the level crossing, heard the sound of bayonet scabbards flapping on the thighs of marching troops. Sergeant Stanley McDougall woke his comrades and they ran to alert nearby elements of the battalion. McDougall, running along the top of the embankment, saw German troops of II Battalion, 229 RIR (II/229 RIR) advancing along the whole front through the mist. Returning with a handful of men, he planned to deploy them behind the unmanned bank to the south. By this time, Germans were throwing hand grenades over the embankment, and one exploded near a Lewis machine gun team in front of McDougall, badly wounding the two-man crew. McDougall, who had previously been a Lewis gunner, grabbed the gun and began to fire it from the hip as he went. First, he shot down two German light machine gun teams as they tried to cross the rails, then, running along the enemy edge of the embankment, saw about 20 Germans waiting for the signal to assault. He turned the gun on them, and as they ran, followed them with its fire. By this time, several of his comrades had been killed or wounded.[26][27][28]

Other members of the 47th Battalion had garrisoned the northern end of the previously unoccupied bank, but the southern half remained open. A group of about 50 Germans of the 6th Company of II/229 RIR, advancing earlier than planned, had overrun the Lewis gun team covering the level crossing, and began advancing southwards behind the embankment to the rear of the right forward company of the battalion. Seeing their movement, McDougall and others opened fire on them. The barrel casing of McDougall's Lewis gun had grown so hot that his left hand became blistered, but he continued to fire it with the help of another sergeant. Of the party of Germans who had penetrated about 150 yd (140 m) beyond the railway line, two officers and 20 men had already been killed. Australian troops converged on the remaining Germans, and they quickly surrendered. A total of one officer and 29 men were captured. For his actions that morning, McDougall was later awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award that could be received by an Australian soldier for gallantry in the face of the enemy.[29][30][31][18]

By this time, the rest of the front line between Albert to beyond Dernancourt was also being heavily attacked. In the north, forward troops of the 48th Battalion were firing almost continuously from the railway line. Attacked by elements of III Battalion, 229 RIR (III/229 RIR) supported by minenwerfers firing from a copse south of Albert, the 48th Battalion easily beat off every German assault. This was despite being caught in enfilade by a machine gun sited on the bridge where the Albert–Amiens road crossed the railway line. Leane directed artillery onto the wood south of Albert from which the minenwerfers were firing. This was the same wood upon which the S.O.S. line of the 10th AFA Brigade had been laid. Just as the Germans were assembling for a renewed assault, a stray British shell exploded a munitions dump, scattering panicked troops of II/229 RIR, many of whom were then shot down by the Australians. The 48th lost only three officers and 59 men during the day's fighting. Wary of sending reinforcements from his support line down the exposed slope to the railway line, Leane sent only four men with two Lewis guns forward during the daylight hours. During the day, the right of the 48th was steadily extended to allow the 47th Battalion to move right in turn.[32][33]

The 47th Battalion's sector was also being heavily attacked by II/229 RIR, and apart from the initial penetration by the 6th Company, they also held the German assault, with assistance from the Lewis guns of the 48th Battalion on their left, who caught the advancing Germans in enfilade.[34] On one occasion a party of the left forward company of the battalion charged over the embankment, chasing the Germans back across the flats into some buildings, and then forcing them out of that cover. Exposed to heavy fire, this small force withdrew back to the railway embankment by noon.[35] When he received reports of the German assault, Imlay sent two platoons of his right support company forward to reinforce the right flank of the battalion front line. However, the exposed slope between the two positions was swept by German machine gun fire and shell fire, and the men could be sent forward only in rushes, well spread out, so this took some time and they suffered casualties. Soon after their arrival, the right forward company inflicted heavy casualties on another German attempt to rush the embankment. Imlay later sent another platoon to reinforce the left flank, and a carrying party with a resupply of hand grenades. In the meantime, Gellibrand placed the 45th Battalion at Imlay's disposal, although they did not immediately move forward from their position behind the 106th Brigade.[36][37] German engineers attempted to place pontoon bridges across the Ancre north of Dernancourt to allow assembling troops to cross, but the pontoons were soon riddled and many engineers killed and wounded by guns of the 12th Machine Gun Company. When Imlay became aware of this concentration of German troops, he ordered a company of the 45th Battalion to move to his support lines. During the day, the 47th Battalion suffered 75 casualties.[35]

The German artillery bombardment was heaviest in the sector held by the right company of the 47th Battalion and the 19th NF on either side of the railway bridge northwest of Dernancourt. About 05:00, I/230 RIR began advancing down the slope from the line of the Morlancourt–Méaulte road in three waves, and was quickly met by Lewis gun fire from the 19th NF, which broke up the movement. The German battalion had barely been able to reach its jumping off point in time, and fell behind its barrage. It continued to advance through the Australian and British barrage south of Dernancourt and quickly moved through the village, part of the battalion reaching the railway embankment. About 09:30, the German shelling in the sector near the bridge lessened. The commander of the right section of the 12th Machine Gun Company, stationed near the bridge with the 19th NF, climbed up the embankment and looking over the rails, saw German bayonets sticking up on the other side. After a quick discussion with the ranking officer of the 19th NF in that area, it was decided they would attack immediately. Charging across the railway line, they pushed the German force back far enough to bring one of the Vickers guns into action. The fire from this gun drove the Germans of I/230 RIR back as far as Dernancourt. Before this counter-attack was launched, Foord, feeling his position to be insecure, requested reinforcement. Two companies of the 18th (Service) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, were sent forward from the 106th Brigade support line, arriving around the time of the counter-attack, although they suffered significant casualties as they moved down the exposed slope. II and III/230 RIR were unable to get through Dernancourt to reinforce I/230 RIR, due to a tremendous Australian and British bombardment that fell on the village as they approached. They sought shelter in the cellars of the village. Any troops that attempted to cross the open ground between the village and the railway were shot down.[38][18][39]

About 10:00, a German force estimated at around two battalions in strength emerged from the village and lined out about 200 yards (180 m) from the embankment among the hedgerows and gardens at the edge of the village. At the same time, a German barrage fell heavily about 200 yards behind the defending troops along the railway line. As ammunition was running low, resupply parties were sent forward from the support line, and the dead and wounded were stripped of what ammunition they had left. This renewed German pressure was focussed mainly on the left forward company of the 19th NF that held the railway bridge, which managed to push a Lewis gun team forward of the embankment to enfilade the assembling Germans. The German barrage increased about 10:25, and casualties mounted among the 19th NF. One of these was Foord, who was wounded in the neck but remained at his post.[40]

From the attack near the railway bridge it became clear that Dernancourt was in German hands, despite a previous assumption that it was still held by patrols of the 35th Division. After the heavy shelling of the village, reports were received that the Germans were withdrawing. About 12:30, the commander of the 106th Brigade requested that the artillery fire on the village stop at 14:00 so he could send patrols into the village in an attempt to secure it. He was unable to mount a proper attack due to losses. He asked Gellibrand to extend the right flank of his line to include the railway bridge to free up his troops to go forward. Imlay was ordered to do this, and to follow up any success the 19th NF achieved, but according to the author of a 47th Battalion history, Craig Deayton, this push into Dernancourt had a "ridiculously optimistic" objective, as the German strength in the village was obvious from the attacks that had been mounted from it.[41][42] Imlay also directed the attached company of the 45th to move down to that sector from his support line as soon as the 19th NF went forward. In the event, the pioneers launched an attack by the remnants of two companies, totalling about 100 men. According to Deayton, once they left the cover of the embankment, they came under heavy machine gun fire from the village, suffered significant casualties and withdrew to their start line. A different version is provided by Davson, the historian of the 35th Division, who states that the 19th NF attack achieved success that was "immediate and remarkable", driving the Germans back into the village leaving many machine guns behind. The 47th did not follow up the pioneers in going forward towards Dernancourt.[43][18][44]

The move of the company of the 45th Battalion down the exposed slope was disastrous, possibly as the company commander had not been advised of the particular difficulties involved. Moving in artillery formation,[d] they were shelled and came under intense machine gun fire; 11 men being killed and 37 wounded. The survivors scrambled to the embankment in small groups.[41][46] Although the Official History is silent on who was responsible for this debacle, in his notebooks, the official historian, Charles Bean, blamed Imlay. About 18:00, Gellibrand optimistically ordered the 47th to push into Dernancourt, but they met massed machine gun fire from the village as soon as they began and quickly retired to the railway line. Deayton describes the two attacks on the village as "ill conceived" and the losses incurred unnecessary, as it was obvious to the troops on the railway line that the village was strongly held by the Germans.[43][47]

The far left flank of the German attack fell on the 104th Brigade near the village of Treux, although with the line south of the Ancre in this area, the defenders were less subject to surprise and had good fields of fire. A post of the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers was located in a deep sunken road in the northeast corner of Marrett Wood, which was southwest of Treux itself. On the evening of 27 March, Monash had ordered the 10th Brigade to establish if the 35th Division really held the wood, and patrols of the 37th Battalion had located the British post in the sunken road and provided some support, consisting of a few snipers and a Lewis gun crew which was low on ammunition. About 06:00, a small German attack was launched in this sector, but it was repelled with Lewis gun fire. About 08:00, Germans were seen approaching in the distance, and the commander of the Lancashire Fusiliers post asked the 37th Battalion for greater support. Before this could arrive, several hundred Germans of II/13 IR attacked, but they were beaten off by the combined British-Australian force at Marrett Wood with the help of the British artillery. The rest of 13 IR attacked further east around the village of Ville, but were easily stopped by the main line of the 106th Brigade. In response to the Lancashire Fusiliers' request for reinforcements, a company of the 38th Battalion occupied Marrett Wood about 11:35, just as another unsuccessful German assault was mounted. A further unsuccessful attempt was made at 16:30. The Germans blamed lack of adequate artillery support for their failure to capture Treux and Marrett Wood.[48][47][49]

Throughout the day, the Australian and British artillery fired on German assembly areas east and south of the railway line. About 16:00, warning was received of a possible German attack north of the Albert–Amiens road, so Gellibrand advised the 46th Battalion, then in reserve, that they might be needed to combine with a company of Medium Mark A Whippet tanks to help repel the forecast attack. About this time, a light drizzle began to fall, and the attack never came. Half an hour after this warning, Germans of III/230 RIR supported by elements of I and II/230 RIR, were seen filtering into houses on the southern outskirts of Albert in the 48th Battalion sector. Artillery was directed into this area, which drove the Germans out again. By 17:00, German troops could be seen withdrawing east in the distance.[50] By this time, the troops of the 12th Brigade had been "moving, marching and fighting for three days and three nights almost without sleep",[51] and were in a state of exhaustion. Increasing rain into the evening made renewal of the German effort less likely.[51] In all, nine attacks were mounted by the Germans on the railway line during the day, and all but the brief penetration into the 47th Battalion sector were beaten off, although the defending troops had suffered significant casualties in doing so. According to Deayton, the defensive deficiencies of the forward positions along the railway line were obvious.[52]

Aftermath

Subsequent operations

The attacks of 28 March were a continuation of the rapid advances that had caused the withdrawal of the hard-pressed Fifth Army since the first days of the Spring Offensive. Prisoners of war taken by the 48th Battalion attested to the fact that this was not a set-piece assault but merely an attack off the line of march with minimal preparation.[53][54] The 50th Reserve Division was in no state to renew the offensive on the following day, and 229 RIR was withdrawn from the line. It had suffered 309 casualties, and 230 RIR had lost another 240.[55]

Despite the withdrawal of the 50th and 65th RFA Brigades on 29 March, the Australian artillery continued to batter Dernancourt, causing another 83 casualties to 230 RIR who were garrisoning the village. The German attempt to renew their advance between Albert and Buire-sur-l'Ancre on 28 March had been completely defeated.[48] Australian casualties amounted to at least 137 killed or wounded,[56] and from 25 to 30 March, the 35th Division suffered 1,540 casualties.[57] The battalions of the 12th and 13th Brigades were awarded the battle honour "Somme 1918" in part for their participation in the battle.[58]

The Germans made two more minor and unsuccessful assaults on the railway embankment south of Albert on 1 and 3 April. They then renewed their offensive in this sector with a determined push on 5 April that was halted by the 4th Division after desperate fighting during the Second Battle of Dernancourt.[59][60] Elsewhere, the Australian 3rd Division fought a sharp action during the First Battle of Morlancourt over the period 28–30 March, followed by heavy fighting further south around Villers-Bretonneux in early April.[56]

Notes

- ^ Marindin had only replaced Major General George McKenzie Franks on 27 March, after the latter had misinterpreted Congreve's verbal orders and directed a withdrawal from the line Albert–Bray-sur-Somme.[8]

- ^ In this and the following map, 19 NF denotes the 19th (Service) Battalion (2nd Tyneside Pioneers) of the Northumberland Fusiliers.[12]

- ^ S.O.S. lines were battlefield control measures that were established by a force in defence so that, at a pre-arranged signal, usually the firing of a flare, the artillery covering a particular sector of the front line would fire a given number of rounds into a chosen area for a specified period. Their main purpose was to ensure immediate defensive fire support in case of an attack, rather than relying on communications back to headquarters and then to the artillery to arrange support.[19]

- ^ Artillery formation was a tactical control measure that involved dispersing platoons and companies into small shallow columns with narrow frontages to limit casualties incurred from enemy artillery fire. For example, a platoon of four sections would move in a diamond formation with a section column at each point of the diamond.[45]

Footnotes

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 236–286.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 189–192.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 114–115, 119–121, 145–152.

- ^ a b Bean 1968, p. 418.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 128.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 153–160.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 160–169.

- ^ Davson 2003, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 174–185.

- ^ Davson 2003, pp. 195–213.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 193.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 356–360.

- ^ a b c Bean 1937, pp. 166, 172–173, 193.

- ^ Devine 1919, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Davson 2003, pp. 213, 215.

- ^ a b c d Edmonds 1937, p. 54.

- ^ Marble 2016, p. 134.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 203.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 197–198, 408–409.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 194.

- ^ Deayton 2011, p. 202.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 199.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 194–195, 198.

- ^ Carlyon 2006, pp. 575–576.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Carlyon 2006, p. 576.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 198–200, 203–204, 206.

- ^ Devine 1919, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b Bean 1937, p. 204.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 202.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 200–203.

- ^ Davson 2003, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Davson 2003, p. 214.

- ^ a b Bean 1937, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Deayton 2011, p. 206.

- ^ a b Deayton 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Davson 2003, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Bull 2014, p. 96.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1937, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Bean 1937, pp. 209–211.

- ^ Davson 2003, p. 215.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 206–208.

- ^ a b Bean 1937, p. 208.

- ^ Deayton 2011, p. 208.

- ^ Deayton 2011, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 236–297.

- ^ Bean 1937, p. 209.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 139.

- ^ Davson 2003, p. 217.

- ^ Baker 1986, p. 295.

- ^ Bean 1937, pp. 356–418.

- ^ Carlyon 2006, pp. 588–589.

References

- Baker, Anthony (1986). Battle Honours of the British and Commonwealth Armies. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-1600-2.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1937). The Australian Imperial Force in France, during the Main German Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. 5 (1 ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 17648469.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1968). Anzac to Amiens: A Shorter History of the Australian Fighting Services in the First World War (5 ed.). Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 5973074.

- Bull, Stephen (2014). Trench: A History of Trench Warfare on the Western Front. Oxford, England: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-0861-5.

- Carlyon, Les (2006). The Great War. Sydney, New South Wales: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-3799-0.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1 ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-611-7.

- Davson, H. M. (2003) [1926]. The History of the 35th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Sifton Praed. ISBN 978-1-84342-643-1.

- Deayton, Craig (2011). Battle Scarred: The 47th Battalion in the First World War. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9870574-0-2.

- Devine, W. (1919). The Story of a Battalion: Being a Record of the 48th Battalion, A.I.F. Melbourne, Victoria: Melville & Mullen. OCLC 3854185.

- Edmonds, James (1937). Military Operations: France and Belgium 1914–1918: 1918, March–April: Continuation of the German Offensives. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 772782397.

- Marble, Sanders (2016). British Artillery on the Western Front in the First World War: 'The Infantry Cannot Do With a Gun Less'. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-95470-9.

Further reading

- Gough, H. de la P. (1968) [1931]. The Fifth Army (repr. Cedric Chivers ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 59766599.

- Shaw Sparrow, W. (1921). The Fifth Army in March 1918 (online ed.). New York: John Lane. pp. 267, 270. OCLC 565269494.