Operation Michael

| Operation Michael | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the German spring offensive in World War I | |||||||||

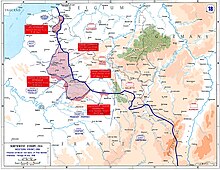

Evolution of the front line during the battle | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 72 divisions |

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 239,800 |

| ||||||||

Operation Michael (German: Unternehmen Michael) was a major German military offensive during World War I that began the German spring offensive on 21 March 1918. It was launched from the Hindenburg Line, in the vicinity of Saint-Quentin, France. Its goal was to break through the Allied (Entente) lines and advance in a north-westerly direction to seize the Channel Ports, which supplied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), and to drive the BEF into the sea. Two days later General Erich Ludendorff, the chief of the German General Staff, adjusted his plan and pushed for an offensive due west, along the whole of the British front north of the River Somme. This was designed to first separate the French and British Armies before continuing with the original concept of pushing the BEF into the sea. The offensive ended at Villers-Bretonneux, to the east of the Allied communications centre at Amiens, where the Allies managed to halt the German advance; the German Army had suffered many casualties and was unable to maintain supplies to the advancing troops.

Much of the ground fought over was the wilderness left by the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The action was therefore officially named by the British Battles Nomenclature Committee as The First Battles of the Somme, 1918, whilst the French call it the Second Battle of Picardy (2ème Bataille de Picardie). The failure of the offensive marked the beginning of the end of the First World War for Germany. The arrival in France of large reinforcements from the United States replaced Entente casualties but the German Army was unable to recover from its losses before these reinforcements took the field. Operation Michael failed to achieve its objectives and the German advance was reversed during the Second Battle of the Somme, 1918 (21 August – 3 September) in the Allied Hundred Days Offensive.[a]

Background

Strategic developments

On 11 November 1917, the German High Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) discussed what they hoped would be a decisive offensive on the Western Front the following spring. Their target was the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), commanded by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, which they believed had been exhausted by the battles in 1917 at Arras, Messines, Passchendaele and Cambrai. A decision to attack was taken by General Erich Ludendorff on 21 January 1918.[2] At the start of 1918, the German people were close to starvation and growing tired of the war.[3] By mid-February 1918, while Germany was negotiating the Russian surrender and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Ludendorff had moved nearly 50 divisions from the east, so that on the Western Front, Germany's troops outnumbered those of the Allied armies. Germany had 192 divisions and three brigades on the Western Front by 21 March, out of 241 in the German Army.[4] There were 110 of these divisions on the front line, and 50 of them faced the smaller British front. With 31 facing the BEF, there were 67 additional divisions in reserve. 318,000 American soldiers were expected in France by May 1918, and another million were expected by August. The Germans knew that the only chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the build-up of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was complete.[5]

The German strategy for the 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser's Battle), involved four offensives, Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau and Blücher–Yorck. Michael took place on the Somme and then Georgette was conducted on the Lys and at Ypres, which was planned to confuse the enemy. Blücher took place against the French in the Champagne region. Although British intelligence knew that a German offensive was being prepared, this far-reaching plan was much more ambitious than Allied commanders expected. Ludendorff aimed to advance across the Somme, then wheel north-west, to cut the British lines of communication behind the Artois front, trapping the BEF in Flanders. Allied forces would be drawn away from the Channel ports, which were essential for British supply; the Germans could then attack these ports and other lines of communication. The British would be surrounded and surrender.[6]

The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, had agreed that the BEF would take over more of the front line, at the Boulogne Conference, against military advice, after which the British line was extended. The "line", taken over from the French, barely existed, needing much work to make it easily defensible to the positions further north, which slowed progress in the area of the Fifth Army (General Hubert Gough). During the winter of 1917–1918, the new British line was established in an arc around St. Quentin, by many small unit actions among the ruined villages in the area. There were many isolated outposts, gaps in the line and large areas of disputed territory and waste land.[7] These positions were slowly improved by building the new three-zone system of defence in depth but much of the work was performed by infantry working-parties.[8] Most of the redoubts in the battle zone were complete by March 1918 but the rear zone was still under construction.[9]

The BEF had been reorganised due to a lack of infantry replacements; divisions were reduced from twelve to nine battalions, on the model established by the German and French armies earlier in the war. It was laid down that the senior regular and first-line territorial battalions were to be retained, in preference to the higher-numbered second-line territorial and New Army battalions. Second-line territorial and New Army divisions were badly disrupted, having in some cases to disband half of their battalions, to make way for units transferred from regular or first-line territorial divisions. Battalions had an establishment of 1,000 men but some had fewer than 500 men, due to casualties and sickness during the winter.[10]

Tactical developments

The German army trained using open-warfare tactics which had proved effective on the Eastern Front, particularly at the Battle of Riga in 1917. The Germans had developed stormtrooper (Stoßtruppen) units, elite infantry which used infiltration tactics, operating in small groups that advanced quickly by exploiting gaps and weak defences.[11] Stoßtruppen bypassed heavily defended areas, which follow-up infantry units could deal with once they were isolated, and occupied territory rapidly to disrupt communication by attacking enemy headquarters, artillery units and supply depots in the rear. Each division transferred its best and fittest soldiers into storm units, from which several new divisions were formed. This process gave the German army an initial advantage in the attack but meant that the best troops would suffer disproportionate casualties, while the men in reserve were of lower quality.[11]

Developments in artillery tactics were also influential. Ludendorff was able to dispense with slow destructive and wire-cutting bombardments by using the large number of artillery pieces and mortars to fire "hurricane" bombardments concentrated on artillery and machine-gun positions, headquarters, telephone exchanges, railways and communication centres. There were three phases to the bombardment: a brief fire on command and communications, then a destructive counter-battery bombardment and then bombardment of front-line positions. The deep bombardment aimed to knock out the opponent's ability to respond; it lasted only a few hours to retain surprise, before the infantry attacked behind a creeping barrage. Such artillery tactics had been made possible by the vast numbers of accurate heavy guns and large stocks of ammunition that Germany had deployed on the Western Front by 1918.[12][b]

An officer of the 51st (Highland) Division wrote: "The year 1917 ... closed in an atmosphere of depression. Most divisions on the Western front had been engaged continuously in offensive operations ... all were exhausted ... and weakened."[14] The last German offensive on the Western Front, before the Cambrai Gegenschlag (counter-stroke) of December 1917, had been against the French at Verdun, giving the British commanders little experience in defence. The development of a deep defence system of zones and trench lines by the Germans during 1917, had led the British to adopt a similar system of defence in depth. This reduced the proportion of troops in the front line, which was lightly held by snipers, patrols and machine-gun posts and concentrated reserves and supply dumps to the rear, away from German artillery. British divisions arranged their nine infantry battalions in the forward and battle zones according to local conditions and the views of commanders; about 1⁄3 of the infantry battalions of the Fifth Army and a similar number in the Third Army held the forward zone.[15]

The Forward Zone was organised in three lines to a depth depending on the local terrain. The first two lines were not held continuously, particularly in the Fifth Army area, where they were in isolated outpost groups in front of an irregular line of supporting posts. The third line was a series of small redoubts for two or four platoons. Posts and redoubts were sited so that intervening ground could be swept by machine-gun and rifle-fire or from machine-guns adjacent to the redoubts. Defence of the Forward Zone depended on fire-power rather than large numbers of troops but in the Fifth Army area a lack of troops meant that the zone was too weak to be able to repulse a large attack. The Battle Zone was also usually organised in three defensive systems, front, intermediate and rear, connected by communication trenches and switch lines, with the defenders concentrated in centres of resistance rather than in continuous lines. About 36 of the 110 infantry and pioneer battalions of the Fifth Army held the Forward Zone. Artillery, trench mortars and machine-guns were also arranged in depth, in positions chosen to allow counter-battery fire, harassing fire on transport routes, fire on assembly trenches and to be able to fire barrages along the front of the British positions at the first sign of attack. Artillery positions were also chosen to offer cover and concealment, with alternative positions on the flanks and to the rear. About 2⁄3 of the artillery was in the Battle Zone, with a few guns further forward and some batteries were concealed and forbidden to fire before the German offensive began.[16]

Prelude

German plan of attack

The Germans chose to attack the sector around St. Quentin taken over by the British from February–April 1917, following the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line.[17]

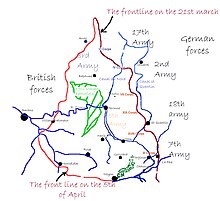

The attacking armies were spread along a 69-kilometre (43 mi) front between Arras, St. Quentin and La Fère. Ludendorff had assembled a force of 74 divisions, 6,600 guns, 3,500 mortars and 326 fighter aircraft, divided between the 17th Army (Otto von Below), 2nd Army (Georg von der Marwitz) of Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht (Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria) and the 18th Army (General Oskar von Hutier), part of Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz (Army Group German Crown Prince) and the 7th Army. The main weight of attack was between Arras and a few kilometres south of St. Quentin, where the 18th Army had 27 divisions. Forty-four divisions were allocated to Operation Michael and called mobile divisions, which were brought up to full strength in manpower and equipment. Men over 35 years old were transferred, a machine-gun unit, air support and a communications unit were added to each division and the supply and medical branches were re-equipped but a chronic shortage of horses and fodder could not be remedied. Around the new year the mobile divisions were withdrawn for training in the latest German attack doctrine.[18]

Training emphasised rapid advance, the silencing of machine-guns and maintaining communication with the artillery, to ensure that infantry and the creeping barrage moved together. Infantry were issued with light machine-guns, mortars and rifle grenades and intensively trained.[19][20] Thirty divisions were trained in the new tactics but had a lower scale of equipment than the elite divisions and the remainder were stripped of material to supply them, giving up most of their remaining draught animals.[21] In the north, two German armies would attack either side of the Flesquières salient, created during the Battle of Cambrai. The 18th Army, transferred from the Eastern Front, planned its attack either side of St. Quentin, to divide the British and French armies. The two northern armies would then attack the British position around Arras, before advancing north-west to cut off the BEF in Flanders. In the south, it was intended to reach the Somme and then hold the line of the river against any French counter-attacks; the southern advance was extended to include an advance across the Somme.[22]

British defensive preparations

In the north, the Third Army (General Julian Byng), defended the area from Arras south to the Flesquières Salient. To the south, the Fifth Army (General Hubert Gough) held the line down to the junction with the French at Barisis. The Fifth Army held the longest front of the BEF, with twelve divisions and three cavalry divisions, 1,650 guns, 119 tanks and 357 aircraft. An average British division in 1918 consisted of 11,800 men, 3,670 horses and mules, 48 artillery pieces, 36 mortars, 64 Vickers heavy machine guns, 144 Lewis light machine-guns, 770 carts and wagons, 360 motorcycles and bicycles, 14 trucks, cars and 21 motorised ambulances.[23]

In the Weekly Intelligence Summary of 10 March 1918, British intelligence predicted a German offensive in the Arras–St. Quentin area based on air reconnaissance photographs and the testimony of deserters; the prediction was reiterated in the next summary on 17 March.[24][25] Allied aircraft had photographed German preparations, new supply roads had been constructed and shell craters had been turned into concealed trench mortar batteries. Heavily laden motorised and horse-drawn transports had been seen heading into St. Quentin from the east, and in the distance German officers were observed studying British lines. The British replied with nightly bombardments of the German front line, rear areas and possible assembly areas.[26] A few days before the attack, two German deserters slipped through No Man's Land and surrendered to the 107th Brigade. They spoke of troops, batteries of artillery and trench mortars massing on the German front. They reported massed trench mortars directly in front of 36th Division lines for wire cutting and an artillery bombardment, lasting several hours, as a preliminary to an infantry assault.[27] During the night of 20 March, troops of the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division conducted a raid on German positions and took more prisoners, who told them that the offensive would be launched the following morning.[28]

At the time of the attack Fifth Army defences were still incomplete. The Rear Zone existed as outline markings only, while the Battle Zone consisted of battalion "redoubts" that were not mutually supporting, and were vulnerable to German troops infiltrating between them.[28] The British ordered an intermittent bombardment of German lines and likely assembly areas at 03:30 and a gas discharge on the 61st Division front. At 04:40 a huge German barrage began along all the Fifth Army front and most of the front of the Third Army.[29]

Battle

Battle of St. Quentin, 21–23 March

Day 1, 21 March

And then, exactly as a pianist runs his hands across the keyboard from treble to bass, there rose in less than one minute the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear...It swept round us in a wide curve of red leaping flame stretching to the north far along the front of the Third Army, as well as of the Fifth Army on the south, and quite unending in either direction...the enormous explosions of the shells upon our trenches seemed almost to touch each other, with hardly an interval in space or time...The weight and intensity of the bombardment surpassed anything which anyone had ever known before.[30]

The artillery bombardment began at 04:35 with an intensive German barrage opened on British positions south west of St. Quentin for a depth of 4–6 km (2.5–3.7 mi). At 04:40 a heavy German barrage began along a 60 km (40 mi) front. Trench mortars, mustard gas, chlorine gas, tear gas and smoke canisters were concentrated on the forward trenches, while heavy artillery bombarded rear areas to destroy Allied artillery and supply lines.[29] Over 3,500,000 shells were fired in five hours, hitting targets over an area of 400 km2 (150 sq mi) in the biggest barrage of the war, against the Fifth Army, most of the front of Third Army and some of the front of the First Army to the north.[31] The front line was badly damaged and communications were cut with the Rear Zone, which was severely disrupted.[32]

When the infantry assault began at 09:40, the German infantry had mixed success; the German 17th and 2nd Armies were unable to penetrate the Battle Zone on the first day but the 18th Army advanced further and reached its objectives.[33] Dawn broke to reveal a heavy morning mist. By 05:00, visibility was barely 10 m (10 yd) in places and the fog was extremely slow to dissipate throughout the morning. The fog and smoke from the bombardment made visibility poor throughout the day, allowing the German infantry to infiltrate deep behind the British front positions undetected.[34] Much of the Forward Zone fell during the morning as communication failed; telephone wires were cut and runners struggled to find their way through the dense fog and heavy shelling. Headquarters were cut off and unable to influence the battle.[35]

Around midday German troops broke through south-west of St. Quentin, reached the Battle Zone and by 14:30 were nearly 3 km (1.9 mi) south of Essigny. Gough kept in contact with the corps commanders by telephone until 15:00 then visited them in turn. At the III Corps Headquarters ("HQ"), he authorised a withdrawal behind the Crozat canal, at the XVIII Corps HQ he was briefed that the Battle Zone was intact and at the XIX Corps HQ found that the Forward Zone on each flank had been captured. Gough ordered that ground was to be held for as long as possible but that the left flank was to be withdrawn, to maintain touch with the VII Corps. The 50th Division was ordered forward as a reinforcement for the next day. On the VII Corps front, Ronssoy had been captured and the 39th Division was being brought forward; on the rest of the front, the 21st and 9th divisions were maintaining their positions and had preserved the link with V Corps of the Third Army in the Flesquières Salient to the north.[36] The Fifth Army "Forward Zone", was the only area where the defences had been completed and had been captured. Most of the troops in the zone were taken prisoner by the Germans who moved up unseen in the fog; garrisons in the various keeps and redoubts had been surrounded. Many parties inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, despite attacks on their trenches with flame throwers. Some surrounded units surrendered once cut off, after running out of ammunition and having had many casualties; others fought to the last man.[37]

In the Third Army area, German troops broke through during the morning, along the Cambrai–Bapaume road in the Boursies–Louverval area and through the weak defences of the 59th Division near Bullecourt.[38] By the close of the day, the Germans had broken through the British Forward Zone and entered the Battle Zone on most of the attack front and had advanced through the Battle Zone, on the right flank of the Fifth Army, from Tergnier on the Oise river to Seraucourt-le-Grand.[39] South-west of St. Quentin in the 36th Division area, the 9th Irish Fusiliers war diary record noted that there had been many casualties, three battalions of the Forward Zone had been lost and three battalions in the Battle Zone were reduced to 250 men each, leaving only the three reserve battalions relatively intact.[25] Casualties in the division from 21–27 March were 6,109, the most costly day being 21 March.[40]

Gough ordered a fighting retreat to win time for reinforcements to reach his army. As the British fell back, troops in the redoubts fought on, in the hope that they would be relieved by counter-attacks or to impose the maximum delay on the German attackers.[41] The right wing of the Third Army also retreated, to avoid being outflanked. The morning fog had delayed the use of aircraft but by the end of the day, 36 squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps had been in action and reported losing 16 aircraft and crew, while having shot down 14 German aircraft; German records show 19 and 8 losses.[42] The first day of the battle had been costly for the Germans, who had suffered c. 40,000 casualties, slightly more than they inflicted on the BEF. The attack in the north had failed to isolate the Flesquières Salient, which had been held by the 63rd Division and the weight of the German offensive was increased in the south, where the 18th Army received six fresh divisions.[43]

Day 2, 22 March

On the second day of the offensive, British troops continued to fall back, losing their last footholds on the original front line. Thick fog impeded operations and did not disperse until early afternoon. Isolated engagements took place as the Germans pressed forward and the British held their posts, often not knowing who was to either side of them. Brigade and battalion control over events was absent. It was a day of stubborn and often heroic actions by platoons, sections and even individuals isolated from their comrades by the fragmented nature of the battle and lack of visibility.[44] The greatest danger facing the British on 22 March was that the Third and Fifth Armies might become separated. Byng did not order a retirement from the Flesquières salient, which his army had won at such cost and Haig ordered him to keep in contact with the Fifth Army, even if that required a further retreat; the day also saw the first French troops enter the battle on the southern flank.[45]

Small parties of British troops fought delaying actions, to allow those to their rear to reach new defensive positions. Some British battalions continued to resist in the Battle Zone and delay the German advance, even managing to withdraw at the last moment. At l'Épine de Dallon the 2nd Wiltshire battalion held out until 14:30 and at "Manchester Hill", the garrison of the 16th Manchesters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Wilfrith Elstob, fought until he was killed at 16:30.[46] Directly to their rear was the "Stevens Redoubt", of the 2nd Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment, to which the survivors retired. The redoubt was reinforced by two companies of the 18th King's and attacked from all sides after the units on the flanks had been pushed back. The Bedfords were ordered to retire just as their ammunition ran out and retreated through the lines of the 20th Division, having lost half their number.[47]

The longest retreat was made in the XVIII Corps area, where corps commander General Ivor Maxse appeared to have misinterpreted an order from Gough for a fighting retreat if necessary, to mean that the corps should fall back to the Somme.[48] The Germans brought heavy artillery into Artemps under the cover of the morning mist, which forced the remaining battalions of the 109th Brigade (36th Division) to retreat to join the 108th Brigade at Happencourt. The result of the misunderstanding between Gough and Maxse and different interpretations placed on boom messages and written orders, was that the 36th Division retired to Sommette-Eaucourt on the south bank of the Canal de Saint-Quentin, to form a new line of defence. This required the Division to cross the Canal at Dury. The daylight withdrawal to the Green Line, over almost 14 km (9 mi), was completed gradually, assisted by the defence of the Ricardo Redoubt whose garrison did not surrender until 16:40.[49] During the retreat, Engineers blew the bridges across the Canal between Ham and Ollézy but the railway bridge at Pithon suffered only minor damage. The Germans were soon over the river and advanced up to 15 kilometres (10 mi) to the Crozat canal.[50]

French troops on the British right flank moved quickly to reinforce, with French commander-in-chief Petain dispatching three divisions before British General Headquarters requested assistance at 2 am and alerting 12 divisions to move forward the next day.[51]

Day 3, 23 March

Early on the morning of Saturday 23 March, German troops broke through the line in the 14th Division sector on the Canal de Saint-Quentin at Jussy. The 54th Brigade were holding the line directly to their south and were initially unaware of their predicament, as they were unknowingly being outflanked and surrounded. The 54th Brigade History records "the weather still favoured the Germans. Fog was thick over the rivers, canals and little valleys, so that he could bring up fresh masses of troops unseen". In the confusion, Brigade HQ tried to establish what was happening around Jussy and by late morning the British were retreating in front of German troops who had crossed the Crozat Canal at many points. All lines of defence had been overrun and there was nothing left to stop the German advance; during the day Aubigny, Brouchy, Cugny and Eaucourt fell.[52]

Lieutenant Alfred Herring of the 6th Northamptonshire Battalion in the 54th Brigade, despite having never been in battle before, led a small and untried platoon as part of a counter-attack made by three companies, against German troops who had captured the Montagne Bridge on the Crozat Canal. The bridge was recaptured and held for twelve hours before Herring was captured with the remnants of his platoon.[53][c]

The remnants of the 1/1st Hertfordshire Regiment were retreating across the southernmost edges of the 1916 Somme battlefield and by the morning of 24 March there were only eight officers and around 450 men left. The war diary read,

Before dawn the Bn marched to BUSSU & dug in hastily on the east side of the village. When both flanks became exposed the Bn retired to a line of trenches covering the PERONNE–NURLU road. After covering the 4/5th Black Watch Regt on the left the Bn withdrew to the ST. DENNIS line which was very stubbornly defended. The Bn then retired with difficulty to the line protecting the PERONNE–CLERY road with the remainder of the 116th Inf. Bde. to cover the retreat of the 117th and 118th Inf. Bdes. When this had been successfully accomplished under very harassing machine gun fire from the enemy, the Bn conformed to the general retirement on CLERY village where it concentrated. The remnants of the Bn then defended a line of trenches between the village and running down to the River SOMME.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 23 March 1918[31]

Ludendorff issued a directive for the "continuation of the operations as soon as the line Bapaume–Peronne–Ham had been reached: 17th Army will vigorously attack in the direction Arras–St Pol, left wing on Miraumont (7 km (4+1⁄2 mi) west of Bapaume). 2nd Army will take Miraumont–Lihons (near Chaulnes) as direction of advance. 18th Army, echeloned, will take Chaulnes–Noyon as direction of advance, and will send strong forces via Ham".[54] The 17th Army was to roll-up British forces northwards and the 2nd Army was to attack west along the Somme, towards the vital railway centre of Amiens. The 18th Army was to head south-west, destroying French reinforcements on their line of march and threatening the approaches to Paris in the Second Battle of Picardy (2e Bataille de Picardie). The advance had been costly and the German infantry were beginning to show signs of exhaustion; transport difficulties had emerged, supplies and much heavy artillery lagged behind the advance.[55]

Actions at the Somme crossings, 24–25 March

Day 4, 24 March

By now, the front line was badly fragmented and highly fluid, as the remnants of the divisions of the Fifth Army were fighting and moving in small bodies, often composed of men of different units. German units advanced irregularly and some British units ended up under French command to the south or behind enemy lines to the east, making the logistic tasks of the corps and divisional staffs nigh impossible. The official historian, Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds wrote:

After three days of battle, with each night spent on the march or occupied in the sorting out and reorganization of units, the troops – Germans as well as British – were tired almost to the limits of endurance. The physical and mental strain of the struggle against overwhelming odds, the heavy losses, the sinister rumours which were rife, all contributed to depress morale.[56]

The 109th brigade planned a counter-attack in the early hours of 24 March but before dawn German troops entered Golancourt, just north-west of Villeselve, so British troops were forced to remain in their defensive positions. The front ran roughly between Cugny and the south of Golancourt.[57] An example of the condition of many British units, was the 54th Brigade of the 18th Division where by nightfall on 23 March, the 7th Bedfordshire and 6th Northamptonshire battalions had c. 206 men each and the 11th Royal Fusiliers had 27 men, who were hurriedly reorganised and then took post in the wood north of Caillouel at 10:00.[58] The battle continued throughout the morning along the entire front and at 11:00, the remnants of the 14th Division were ordered to withdraw further south to the town of Guiscard. A series of small German attacks dislodged the exhausted British troops piecemeal and gaps in the front created by this staggered withdrawal were exploited by the Germans. The 54th Brigade was slowly outflanked by attacks from the north-east and north-west, the brigade fell back into Villeselve and were heavily bombarded by German Artillery from around 12:00. British troops, supported by French infantry attempted to hold the line here but the French received orders to retreat, leaving the British flank exposed; the British retreated with the French and fell back through Berlancourt to Guiscard.[59] The 54th Brigade ordered the retirement of what was left of its battalions to Crepigny and at 03:00 on 25 March they slipped away under cover of darkness to Beaurains.[60] Further north, the 1/1st Hertfordshires war diary read,

After an intense bombardment of our trenches the enemy attacked with large numbers. The Bn, after heavy fighting, retired to a crest in front of the FEVILLERS-HEM WOOD ROAD. Here the Bn lost its Commanding Officer, Lieut. Colonel E. C. M. PHILLIPS, about whom, up to the time of writing, nothing is known. In the evening the Bn got orders to withdraw through the 35th Division to MARICOURT where the Bn spent the night.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 24 March 1918[31]

By nightfall, the British had lost the line of the Somme, except for a stretch between the Omignon and the Tortille. The fighting and retirements in the face of unceasing pressure by the 2nd Army led the right of the Third Army to give up ground as it tried to maintain contact with the left flank of Fifth Army.[61]

First Battle of Bapaume, 24–25 March

Day 4, 24 March

In the late evening of 24 March, after enduring unceasing shelling, Bapaume was evacuated and then occupied by German forces on the following day.[62] The British official historian, Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds, wrote:

The whole of the Third Army had swung back, pivoting on its left, so that, although the VI and XVII Corps were little behind their positions of the 21st March, the right of V Corps had retired seventeen miles [27 km]. The new line, consisting partly of old trenches and partly shallow ones dug by the men themselves, started at Curlu on the Somme and ran past places well known in the battle of the Somme, the Bazentins and High Wood, and then extended due north to Arras. It was, for the most part, continuous, but broken and irregular in the centre where some parts were in advance of others; and there were actually many gaps... Further, the men of the right and centre corps ... were almost exhausted owing to hunger and prolonged lack of sleep.[63]

After three days the infantry was exhausted and the advance bogged down, as it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies over the Somme battlefield of 1916 and the wasteland of the 1917 German retreat to the Hindenburg Line. German troops had also examined abandoned British supply dumps which caused some despondency, when German troops found out that the Allies had plenty of food despite the U-boat campaign, with luxuries such as chocolate and even Champagne falling into their hands.[64] Fresh British troops had been hurried into the region and were moved towards the vital rail centre of Amiens.[65]

The German breakthrough had occurred just to the north of the boundary between the French and British armies. The new focus of the German attack came close to splitting the British and French armies. As the British were forced further west, the need for French reinforcements became increasingly urgent.[66] In his diary entry for 24 March, Haig acknowledged important losses but derived comfort from the resilience of British rearguard actions,

By night the Enemy had reached Le Transloy and Combles. North of Le Transloy our troops had hard fighting; the 31st, Guards, 3rd, 40th and 17th Divisions have all repulsed heavy attacks and held their ground.[67]

Late that night Haig (after first dining with General Byng when he urged Third Army to "hold on ... at all costs") travelled to Dury to meet the French commander-in-chief, General Pétain, at 23:00. Pétain was concerned that the British Fifth Army was beaten and that the "main" German offensive was about to be launched against French forces in Champagne.

Historians differ as to the immediate British reaction. The traditional account, as repeated in Edmonds' Official History, composed during the 1920s, describes Petain as informing Haig on 24 March, that the French army were preparing to fall back towards Beauvais to protect Paris if the German advance continued.[68] This would create a gap between the British and French armies and force the British to retreat towards the Channel Ports. The traditional account then describes Haig as sending a telegram to the War Office to request an Allied conference.[69] More recent historians view this view as a fabrication: the earlier manuscript version of Haig's diary, rather than the edited typeset version, is silent on the supposed telegram and Petain's willingness to abandon the British for Paris (a withdrawal which is also geographically implausible).[70]

Day 5, 25 March

The movements of 25 March were extremely confused and reports from different battalions and divisions are often contradictory. An unidentified officer's account of his demoralising experiences that day is quoted in the British official history:

What remains in my memory of this day is the constant taking up of new positions, followed by constant orders to retire, terrible blocks on the roads, inability to find anyone anywhere; by exceeding good luck almost complete freedom from shelling, a complete absence of food of any kind except what could be picked up from abandoned dumps.[63]

The focus of fighting developed to the north of the 54th Brigade, who were now joined with the French and the survivors of the 18th Division, who could scarcely raise enough men to form a small Brigade. By 10:00 on the 25th, the left flank of 7th Bedfordshires was again exposed as the French around them retreated, so another retirement was ordered. They withdrew back to Mont Du Grandu further south and away from the British Fifth Army. Midday saw them in a stronger position until French artillery and machine guns opened fire on them, mistaking them for Germans, forcing them to retire to high ground west of Grandu.[31]

The remaining troops of the 36th Division were ordered to withdraw and reorganise. To give support to French troops now holding the front, they set off on a 24-kilometre (15 mi) march west. Around midday, they halted for a few hours rest near Avricourt. While there they received orders to head for a new line which would be formed between Bouchoir and Guerbigny. During the day, the Germans made a rapid advance and Allied troops and civilians with laden carts and wagons filled the roads south and west. The Germans passed through Libermont and over the Canal du Nord. Further north, the town of Nesle was captured, while south-west of Libermont German troops faced the French along the Noyon–Roye road. The 1/1st Herts having spent the night in Maricourt, "marched from MARICOURT to INSAUNE. The march was continued after breakfast across the River SOMME at CAPPY to CHUIGNOLLES, where the Bn reorganised and spent the night." (1/1 Herts war diary, 25 March 1918).[31][d]

More orders were received at 3pm to move to Varesnes on the south bank of the River Oise but whilst en-route they were countermanded with surprise orders to counter attack and retake a village called Babouef. Therefore, the war worn Brigade who had been fighting and marching for four punishing days solid were about faced and moved off to the attack with an enthusiasm that is nothing short of incredible. By rights, the Brigade should have been incapable of the action yet those quoted as being there remark that it was the most memorable event of the entire rearguard action. At 5pm, with the Fusiliers on the right, the Bedfords on the left and the Northamptons in reserve, the Brigade formed up with the Babouef to Compeigne road on their right and the southern edge of the woods above Babouef to their left. The Germans had not expected a British counter attack, thinking there was nothing but ragged French units in their area, so were surprised at the arrival of three small but determined British battalions. They put little fight up and many Germans fell in the hand to hand fighting that lasted for around 20 minutes before the village was secured and the remaining enemy – that could get away – fled. Ten machine guns and 230 German prisoners were taken with very light casualties recorded by the Brigade; an incredible feat whatever way you view it. They dug in on the German side of the village amongst the cornfields and settled in for the night. Cooking limbers were even brought up and the idea of a quiet night gave the exhausted men a welcomed break from the extreme stress they had all been through in the past five days. Unfortunately, their rest did not last long.[71]

The RFC flew sorties at low altitude in order to machine-gun and bomb ground targets and impede the German advance. On 25 March, they were particularly active west of Bapaume.[72] [e] Rearguard actions by the cavalry in the Third Army slowed the German advance but by 18:00 Byng had ordered a further retirement beyond the Ancre. Through the night of 25 March, the men of the Third Army attained their positions but in the process gaps appeared, the largest of over 6 km (4 mi) between V and VI Corps.[73] Sir Henry Wilson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, arrived at General Headquarters at 11:00 on 25 March, where they discussed the position of the British Armies astride the river Somme. Haig wanted at least twenty French divisions to help defend Amiens and delivered a message for the French Premier Clemenceau.[74] The Doullens Conference took place the next day.[75]

Battle of Rosières, 26–27 March

Day 6, 26 March

The Allied conference took place on 26 March at Doullens. Ten senior Allied politicians and generals were present, including the French President, British Prime Minister, Minister of Munitions Winston Churchill, and Generals Pétain, Foch, Haig and Wilson. The result of the meeting was that General Foch was first given command on the Western Front and then made Generalissimo of the Allied forces.[76] It was agreed to hold the Germans east of Amiens and an increasing number of French formations would reinforce the Fifth Army, eventually taking over large parts of the front south of Amiens.[77]

Ludendorff issued new orders on 26 March. All three of his armies were given ambitious targets, including the capture of Amiens and an advance towards Compiègne and Montdidier, which fell on 27 March.[78] Edmonds, the official historian, noted:

On 26 March, the general direction of the two northern German Armies of attack, the 2nd and 17th, was still due west; the 18th Army opened fanwise, its northern boundary some six miles [10 km], south of the Somme at Peronne, running west, but its southern one near Chauny, pointing south-west.

In the north, the

17th Army ... met with very determined resistance, but it was hoped, with the aid of the 2nd Army on the south, which had not encountered so much opposition, and of new attacks – "Mars" and "Valkyrie" ... on the north [towards Arras] that the 17th would be able to get going again.[79]

A gap in the British line near Colincamps was held by newly arrived elements of the New Zealand Division that had moved to the line Hamel–Serre to close the gap. They were assisted by British "Whippet" tanks which were lighter and faster than the Mark IVs. This was their first time in action. At around 13:00, "twelve Whippets of the 3rd Tank Battalion suddenly appeared from Colincamps, which they had reached at midday, and where there were only two infantry posts of the 51st Div. Debouching from the northern end of the village, they produced an instantaneous effect. Some three hundred of the enemy, about to enter it from the east, fled in panic. A number of others, finding their retreat cut off, surrendered to some infantry of the 51st Divn…"[80] Despite this success German pressure on Byng's southern flank and communication misunderstandings resulted in the premature retirement of units from Bray and the abandonment of the Somme crossings westwards. To the south of the Somme the 1/1st Herts were:

... moved forward through CHUIGNES to a line in front of the CHUIGNES-FOUCACOURT road I support to the 117th and 118th Bdes. After covering their retirement the Bn fought a series of rearguard actions on the many ridges in front of the village of CHUIGNOLLES. In the afternoon the Bn occupied the PROYART-FROISSY road. Orders were given for the Bn to withdraw behind PROYART, astride the FOUCACOURT-MANOTTE road.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 26 March 1918[31]

French forces on the extreme right (south) of the line under the command of General Fayolle were defeated and fell back in the face of protracted fighting; serious gaps appeared between the retreating groups.

Of the front between the Oise and the Somme, the French held 18 miles [29 km] and the British 19 miles [31 km]. It was for the greater part a continuous line; but there was a three-mile [5 km] space between the French left at Roye and the right of the XIX Corps at Fransart... To fill the gap there were available the remains of the four divisions, the 20th, 36th, 30th and 61st, of the XVIII Corps. These General Maxse had instructed to assemble at and north-west of Roye, in order to keep connection between Robillot's Corps and the XIX Corps and to ensure that if the Allied Armies separated, the XVIII Corps might still remain with the Fifth Army.[81]

Most of the 36th Division had arrived in their new lines around 02:00 on 26 March, and were able to sleep for about six hours, the longest continuous sleep they had in six days, as German troops occupied Roye. The 9th Irish Fusiliers were a long way behind the rest of the Division, delayed by their action north of Guiscard the night before and their retreat was a 50-kilometre (30 mi) continuous night march from Guiscard to Erches, along the Guerbigny–Bouchoir road. They route-marched through Bussy to Avricourt, then on to Tilloloy, Popincourt, Grivillers, Marquivillers and finally via Guerbigny to Erches, where they arrived, completely exhausted, around 11:00 on 26 March. The German troops who took Roye during the early hours of the morning, continued to advance on the Bouchoir–Guerbigny line and by mid-morning were in Andechy, 5.6 kilometres (3+1⁄2 mi) from the new British line.[82]

Day 7, 27 March

The town of Albert was relinquished during the night of 26/27 March,

With the choice of holding the old position on the heights east of Albert, on the left bank of the Ancre, or the high ground west of the devastated town, it had been decided to adopt the latter course. The ruins of Albert were therefore abandoned to the enemy.[83]

The town was then occupied by German troops who looted writing paper, wine and other items they found.[64] 27 March saw a series of continuous complex actions and movements during the defensive battle of XIX Corps against incessant German attacks from the north, east and north-west around Rosières, less than 30 kilometres (20 mi) east of Amiens. This was a consequence of the precipitate abandonment of Bray and the winding line of the Somme river, with its important bridgeheads westwards towards Sailly-le-Sec, by the Third Army on the afternoon of 26 March.[84] The important communications centre of Montdidier was lost by the French on 27 March.[85] [f]

The 1/1st Herts war diary reads:

The Bn who were in trenches on both sides of the road were ordered to move forward in support of the 118th Bde, being temporarily attached to the 4/5th Black Watch Regt. Soon after moving forward British troops were seen retiring to the left in large numbers. Consequently the Bn was ordered to move forward to the left and cover their withdrawal. After having skilfully carried this out the Bn conformed to the general withdrawal to a line between MORCOURT and the FOUCACOURT–LAMOTTE road. The Bn collected and assembled, then counter attacked the enemy, driving him back to within a few hundred yards of the village of MORCOURT.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 27 March 1918[31]

Third Battle of Arras, 28–29 March

Day 8, 28 March,

The focus of the German attack changed again on 28 March. The Third Army, around Arras, that would be the target of Operation Mars. Twenty-nine divisions attacked the Third Army and were repulsed. German troops advancing against the Fifth Army, from the original front at St. Quentin, had penetrated some 60 km (40 mi) by this time, reaching Montdidier. Rawlinson replaced Gough, who was "Stellenbosched" (sacked) despite having organised a long and reasonably successful retreat given the conditions.[87]

The offensive saw a great wrong perpetrated on a distinguished British commander that was not righted for many years. Gough's Fifth Army had been spread thin on a 42-mile [68 km] front lately taken over from the exhausted and demoralized French. The reason why the Germans did not break through to Paris, as by all the laws of strategy they ought to have done, was the heroism of the Fifth Army and its utter refusal to break. They fought a 38-mile [61 km] rearguard action, contesting every village, field and, on occasion, yard ... With no reserves and no strongly defended line to its rear, and with eighty German divisions against fifteen British, the Fifth Army fought the Somme offensive to a standstill on the Ancre, not retreating beyond Villers-Bretonneux.

— Roberts[88]

The German attack against the Third Army was less successful than that against the Fifth Army. The German 17th Army east of Arras advanced only 3 km (2 mi) during the offensive, largely due to the British bastion of Vimy Ridge, the northern anchor of the British defences. Although Below made more progress south of Arras, his troops posed less of a threat to the stronger Third Army than the Fifth Army, because the British defences to the north were superior and because of the obstacle of the old Somme battlefield. Ludendorff expected that his troops would advance 8 km (5 mi) on the first day and capture the Allied field artillery. Ludendorff's dilemma was that the parts of the Allied line that he needed to break most were also the best defended. Much of the German advance was achieved quickly but in the wrong direction, on the southern flank where the Fifth Army defences were weakest. Operation Mars was hastily prepared, to try to widen the breach in the Third Army lines but was repulsed, achieving little but German casualties.[89]

The Herts war diary reads:

The position gained was held stubbornly against all enemy attempts to retake it. On the morning of the 28th orders were received for a speedy evacuation of this line. The enemy at this point was well in our rear in possession of LAMOTTE so that the withdrawal had to be done quickly. The Bn showed the utmost resource during this dangerous manoeuvre, loosing [sic] very few men. The retirement took place in daylight through HARBONNIERS & CAIX. At the latter place the Bn attacked the enemy successfully but thereafter had orders to retire on COYEUX where it again assembled in a counter attack in which the acting Commanding Officer was wounded. During the day rearguard actions took place along the river bed to IGNAUCOURT. In the evening the Bn went into trenches in front of AUBERCOURT.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 28 March 1918[31]

Day 9, 29 March

The Herts war diary reads:

The enemy remained fairly quiet except for machine gun fire.

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 29 March 1918[31]

Day 10, 30 March

The last general German attack came on 30 March. Von Hutier renewed his assault on the French, south of the new Somme salient, while von der Marwitz launched an attack towards Amiens (First Battle of Villers-Bretonneux, 30 March – 5 April). Some British ground was lost but the German attack was rapidly losing strength. The Germans had suffered massive casualties during the battle, many to their best units and in some areas the advance slowed, when German troops looted Allied supply depots.[90]

The Herts war diary reads:

Today (March 30) saw the enemy advancing on the right flank on the other side of the river de LUCE. He very soon enfiladed our positions both with artillery and machine guns. This was followed by a strong enemy bombardment and attack on our front. After a stubborn resistance the Bn fell back to the BOIS DE HANGARD, making two counter attacks en route. (Comment: Lt John William CHURCH died from his wounds and Lt Angier Percy HURD was killed on 30-3-18).

— 1/1 Herts war diary, 30 March 1918[31]

Battle of the Avre, 4 April 1918

Day 14, 4 April

The final German attack was launched towards Amiens. It came on 4 April, when fifteen divisions attacked seven Allied divisions on a line east of Amiens and north of Albert (towards the Avre River). Ludendorff decided to attack the outermost eastern defences of Amiens centred on the town of Villers-Bretonneux. His aim was to secure that town and the surrounding high ground from which artillery bombardments could systematically destroy Amiens and render it useless to the Allies. The fighting was remarkable on two counts: the first use of tanks simultaneously by both sides in the war and a night counter-attack hastily organised by the Australian and British units (including the exhausted 54th Brigade) which re-captured Villers-Bretonneux and halted the German advance.[91] From north to south, the line was held by the 14th Division, 35th Australian Battalion and 18th Division. By 4 April the 14th Division fell back under attack from the German 228th Division. The Australians repulsed the 9th Bavarian Reserve Division and the British 18th Division held off the German Guards Ersatz Division and 19th divisions in the First Battle of Villers-Bretonneux.[92]

Battle of the Ancre, 5 April

Day 15, 5 April

An attempt by the Germans to renew the offensive on 5 April failed and by early morning, the British had forced the enemy out of all but the south-eastern corner of the town. German progress towards Amiens had reached its furthest westward point and Ludendorff terminated the offensive.[93]

Aftermath

Analysis

The Germans had captured 3,100 km2 (1,200 sq mi) of France and advanced up to 65 km (40 mi) but they had not achieved any of their strategic objectives. Over 75,000 British soldiers had been taken prisoner and 1,300 artillery pieces and 200 tanks were lost.[94] It was of little military value with the casualties suffered by the German elite troops and the failure to capture Amiens and Arras. The captured ground was hard to move over and difficult to defend, as much of it was part of the shell-torn wilderness left by the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Elsewhere the transport infrastructure had been demolished and wells poisoned during the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917. The initial German jubilation at the successful opening of the offensive soon turned to disappointment as it became clear that the attack had not been decisive.[95] Marix Evans wrote in 2002, that the magnitude of the Allied defeat was not decisive, because reinforcements were arriving in large numbers, that by 6 April the BEF would have received 1,915 new guns, British machine-gun production was 10,000 per month and tank output 100 per month. The appointment of Foch as Generalissimo at the Doullens Conference had created formal unity of command in the Allied forces.[96]

Casualties

In the British Official History (1935) Davies, Edmonds and Maxwell-Hyslop wrote that the Allies lost c. 255,000 men of which the British suffered 177,739 killed, wounded and missing, 90,882 of them in the Fifth Army and 78,860 in the Third Army, of whom c. 15,000 died, many with no known grave.[97] The greatest losses were to 36th (Ulster) Division, with 7,310 casualties, the 16th (Irish) Division, with 7,149 casualties and 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division, 7,023 casualties.[98] All three formations were destroyed and had to be taken out of the order of battle to be rebuilt. Six divisions lost more than 5,000 men.[98]

German losses were 250,000 men, many of them irreplaceable élite troops. German casualties, from 21 March – 30 April, which includes the Battle of the Lys, are given as 348,300.[97] A comparable Allied figure over this longer period, is French: 92,004 and British: 236,300, a total of c. 328,000.[97] In 1978 Middlebrook wrote that casualties in the 31 German divisions engaged on 21 March were c. 39,929 men and that British casualties were c. 38,512.[99] Middlebrook also recorded c. 160,000 British casualties up to 5 April, 22,000 killed, 75,000 prisoners and 65,000 wounded; French casualties were c. 80,000 and German casualties were c. 250,000 men.[100] In 2002, Marix Evans recorded 239,000 men, many of whom were irreplaceable Stoßtruppen; 177,739 British casualties of whom 77,000 had been taken prisoner, 77 American casualties and 77,000 French losses, 17,000 of whom were captured.

The Allies also lost 1,300 guns, 2,000 machine-guns and 200 tanks.[96] In 2004, Zabecki gave 239,800 German, 177,739 British and 77,000 French casualties.[101]

Cultural references

R. C. Sherriff's play Journey's End (first produced 1928) is set in an officers' dugout in the British trenches facing Saint-Quentin from 18 to 21 March, before Operation Michael. There are frequent references to the anticipated "big German attack" and the play concludes with the launch of the German bombardment, in which one of the central characters is killed.[102]

In John Buchan’s 1919 book Mr Standfast the battle is the culmination of an espionage operation.

In Battlefield 1, two maps represent Operation Michael: St. Quentin Scar and Amiens.[citation needed]

In Tad Williams' Otherland: City of Golden Shadow the first character introduced to the reader is Paul Jonas, who is fighting for the Allies on the Western Front somewhere near Ypres and Saint-Quentin on 24 March 1918.

The 1966 movie The Blue Max depicts Operation Michael as the big German offensive Bruno Stachel's (George Peppard) squadron is supporting with strafing attacks and aerial combat against Allied air forces. At a squadron party celebrating one pilot's award of the Blue Max medal, the General (James Mason) announces the pending barrage of 6,000 guns on the Western Front, refers to the recent defeat of Russia which allowed the release of troops from the East to reinforce the Western armies, and expresses the hope of the High Command that victory in the offensive before America can effectively intervene will win the war for Germany. The second half of the movie following the intermission begins with the breakdown of the German attack and the armies being forced into retreat.

See also

Notes

- ^ Battles and actions described follow the publication: The Official Names of the Battles and Other Engagements Fought by the Military Forces of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–1919 and the Third Afghan War, 1919: Report of the Battles Nomenclature Committee as approved by the Army Council.[1]

- ^ Allied commentators described German infantry attack methods as Hutier tactics because General Oskar von Hutier had commanded the attack on Riga in late 1917 and because the 18th Army under his command had advanced the furthest during Operation Michael but the methods used in 1918 had been developed in the trench warfare of the Western Front 1915–1917. German artillery tactics in 1918 were also the product of years of development but became ascribed to Colonel Georg Bruchmüller, who had planned the artillery bombardment for the attack on Riga, due to his "talent as a self-publicist" after the war.[13]

- ^ Lieutenant Herring was awarded a Victoria Cross when repatriated after the war.[53]

- ^ An example of the rearguard action fought by the Fifth Army is given on a website dedicated to the Bedfordshire regiment.[31]

- ^ The physical and mental stress on the RFC pilots engaged in ground strafing, is detailed in Winged Victory, a semi-autobiographical novel by V. M. Yeates of 46 Squadron, who was shot down by machine-gun fire on 25 March 1918.

- ^ Lieutenant Colonel John Stanhope Collings-Wells, VC, DSO won a posthumous Victoria Cross for his handling of the 4th Bedfordshires throughout the battle.[86]

Footnotes

- ^ James 1924, pp. 26–31.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 140.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 10.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 142.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 139.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 144.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 123.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 40.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 51–56.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, p. 157.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Samuels 1995, pp. 231, 251.

- ^ Sheffield 2011, p. 258.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Falls 1940, pp. 110–116.

- ^ Kitchen 2001, p. 288.

- ^ Samuels 1995, p. 247.

- ^ Kitchen 2001, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Kitchen 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 144–151.

- ^ Grey 1991, p. ?.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Chester 2010, p. March 1918.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 111.

- ^ Falls 1922, p. 192.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, pp. 94–99.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, p. 162.

- ^ Churchill 1938, p. 768.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fuller 2013.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 162–165, 168.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 260–263.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 170–182.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 176, 194–196.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 167–187, 258.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 196, 207–208.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, p. 18.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 207–208, 304.

- ^ Grey 1991, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 262.

- ^ Rowan 1919, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 271.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 177.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 274.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 266.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 272.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 299.

- ^ Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2004). "Myth and Memory: Sir Douglas Haig and the Imposition of Allied Unified Command in March 1918". The Journal of Military History. 68 (3): 788. doi:10.1353/jmh.2004.0112. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 159845369.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 328, 343.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 396.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 323, 398.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 400.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 405.

- ^ Nichols 1922, p. 291.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 406.

- ^ Nichols 1922, pp. 293–298.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 427.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 438–439.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, p. 470.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1935, pp. 413, 444, 492, 519.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 392.

- ^ Sheffield & Bourne 2005, p. 391.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 448.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 450.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2004, pp. 791, 811.

- ^ Rowan 1919, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 472.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 491–492.

- ^ Sheffield & Bourne 2005, p. 393.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 538–544.

- ^ Cruttwell 1940, p. 510.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 544.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 536.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 526.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 496–497.

- ^ Falls 1922, pp. 219–222.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 518.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, p. 523.

- ^ Edmonds 1935, pp. 496, 509–517, 532.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, p. 34.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Roberts 2006, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, pp. 64–75.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, pp. 87–137.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, p. 127.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, pp. 121–129.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, pp. 130–137.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, p. 489.

- ^ Edmonds 1937, p. 137.

- ^ a b Marix Evans 2002, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Edmonds 1937, p. 490.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1937, p. 491.

- ^ Middlebrook 1978, p. 322.

- ^ Middlebrook 1978, p. 347.

- ^ Zabecki 2004, p. 349.

- ^ Sherriff 1937, pp. 1–204.

Bibliography

Books

- Churchill, W. S. C. (1928) [1923–1931]. The World Crisis (Odhams ed.). London: Thornton Butterworth. OCLC 4945014.

- Cruttwell, C. R. M. F. (1982) [1940]. A History of the Great War 1914–1918 (repr. ed.). London: Granada. ISBN 0-586-08398-7.

- Edmonds, J. E.; et al. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-219-5.

- Edmonds, J. E.; et al. (1995) [1937]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1918: March–April: Continuation of the German Offensives. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-223-3.

- Falls, C. (1922). The History of the 36th (Ulster) Division (Constable 1996 ed.). Belfast: McCaw, Stevenson & Orr. ISBN 0-09-476630-4.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-180-6.

- Gray, R. (1991). Kaiserschlacht 1918: the Final German Offensive. Osprey Campaign Series. Vol. XI. London: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-157-2.

- Hart, P. (2008). 1918: A Very British Victory. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-29784-652-9.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 0-948130-18-0.

- Kitchen, M. (2001). The German Offensives of 1918. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0752417991.

- Marix Evans, M. (2002). 1918: The Year of Victories. London: Arcturus. ISBN 0-572-02838-5.

- Middlebrook, M. (1983) [1978]. The Kaiser's Battle 21 March 1918: The First Day of the German Spring Offensive (Penguin ed.). London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-14-005278-X.

- Nichols, G. H. F. (2004) [1922]. The 18th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Blackwood. ISBN 1-84342-866-0.

- Roberts, A. (2006). A History of the English Speaking Peoples Since 1900. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-29785-076-8.

- Rowan, E. W. J. (1919). The 54th Infantry Brigade, 1914–1918; Some Records of Battle and Laughter in France. London: Gale & Polden. OCLC 752706407. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Samuels, M. (1995). Command or Control? Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies 1888–1918. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4214-2.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheffield, G.; Bourne, J. (2005). Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914–1918. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297847023.

- Sherriff, R. C. (1937). Journey's End: A Play in three Acts. New York: Coward-McCann. OCLC 31307878.

Theses

- Zabecki, D. T. (2004). Operational Art and the German 1918 Offensives (PhD) (online ed.). London: Cranfield University, Department of Defence Management and Security Analysis. hdl:1826/3897. ISBN 0-41535-600-8. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

Websites

- Chester, A. G. (2003–2010). "War Diary of the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers, 1 September 1917 to 9 June 1919". Official War Diaries (Ref. WO 95/2505). Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Fuller, S. (2013). "1918 War Diary". The Bedfordshire Regiment in the Great War. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

Further reading

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1934]. The War in the Air Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. IV (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-415-0. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1999). "Winning the War". In Dennis, P.; Grey, J. (eds.). 1918 Defining Victory: Proceedings of the Chief of Army's History Conference Held at the National Convention Centre, Canberra, 29 September 1998. Canberra: Army History Unit. ISBN 0-73170-510-6.

- Roberts, P.; Tucker, S., eds. (2005). The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- Yeates, V. M. (1974) [1934]. Winged Victory (Mayflower ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-58312-287-6.