Firuz Shah Tughlaq

| Firuz Shah Tughlaq | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firuz Shah Tughlaq ibn Malik Rajjab | |||||

Firoz Shah Tughlaq making Dua | |||||

| 19th Sultan of Delhi | |||||

| Reign | 23 March 1351 – 20 September 1388 | ||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad bin Tughluq | ||||

| Successor | Tughluq Khan | ||||

| Born | 1309 Jaunpur | ||||

| Died | 20 September 1388 (aged 78–79) Jaunpur | ||||

| Burial | 20 September 1388 Tomb of Firoz Shah at Jaunpur, Jaunpur | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Tughlaq | ||||

| Dynasty | Tughlaq dynasty | ||||

| Father | Malik Rajab | ||||

| Mother | Bibi Naila | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Hanafi) | ||||

Firuz Shah Tughlaq (Persian: فیروز شاه تغلق, romanized: Fīrūz Shāh Tughlaq; 1309 – 20 September 1388) was the 19th sultan of Delhi from 1351 to 1388.[1][2][3] A Muslim ruler from the Tughlaq dynasty, He succeeded his cousin Muhammad bin Tughlaq following the latter's death at Thatta in Sindh, where Muhammad bin Tughlaq had gone in pursuit of Taghi the rebellious Muslim governor of Gujarat. For the first time in the history of the Sultanate, a situation was confronted wherein nobody was ready to accept the reins of power. With much difficulty, the camp followers convinced Firuz to accept the responsibility. In fact, Khwaja Jahan, the Wazir of Muhammad bin Tughlaq had placed a small boy on the throne claiming him to be the son of Muhammad bin Tughlaq,[4] who meekly surrendered afterwards.

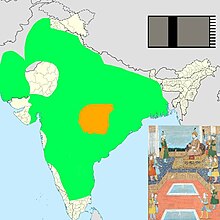

Due to widespread unrest, his realm was much smaller than Muhammad's. Tughlaq was forced by rebellions to concede virtual independence to Bengal and other provinces. He established Sharia across his realm.[5]

Background

His father's name was Rajab (the younger brother of Ghazi Malik) who had the title Sipahsalar. His mother Naila, a Hindu woman, was the daughter of Raja Mal from a concubine of Dipalpur which is now in the Punjab region of Pakistan.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Rule

We know of Firuz Shah Tughlaq in part through his 32-page autobiography, titled Futuhat-i- Firuz Shahi.[13][14] He was 42 when he became Sultan of Delhi in 1351. He ruled until 1388. At his succession, after the death of Muhammad Tughlaq, he faced many rebellions, including in Bengal, Gujarat and Warangal. Nonetheless, he worked to improve the infrastructure of the empire building canals, rest-houses and hospitals, creating and refurbishing reservoirs and digging wells. He founded several cities around Delhi, including Jaunpur, Firozpur, Hissar, Firozabad, Fatehabad.[15] Most of Firozabad was destroyed as subsequent rulers dismantled its buildings and reused the spolia as building materials,[16] and the rest was subsumed as New Delhi grew.

Religious and administrative policies

Tughlaq was a Salafi Muslim who tried to uphold the laws of Islam and adopted Sharia policies. He made a number of important concessions to theologians.[citation needed] He tried to ban practices that the orthodox theologians considered un-Islamic, an example being his prohibition of the practice of Muslim women going out to worship at the graves of saints. He persecuted a number of sects that were considered heretical by the Muslim theologians. Tughlaq took to heart the mistakes made during his cousin Muhammad's rule. He decided not to reconquer areas that had broken away, nor to keep further areas from taking their independence. He was indiscriminately benevolent and lenient as a sultan.[17] He decided to keep nobles and the Ulema happy so that they would allow him to rule his kingdom peacefully.

"The southern states had drifted away from the Sultanate and there were rebellions in Gujarat and Sindh", while "Bengal asserted its independence." He led expeditions to against Bengal in 1353 and 1358. He captured Cuttack, desecrated the Jagannath Temple, Puri, and forced Raja Gajpati of Jajnagar in Orissa to pay tribute. He converted Chauhan Rajputs from Hinduism to Islam in the 14th century[citation needed]. They are now known as Qaimkhanis in Rajasthan.

Hindus who resisted Islamic rule faced severe consequences. Firoz Shah led punitive expeditions against regions such as Kangra and Jajnagar (modern Odisha), where his forces massacred thousands of Hindus, desecrated temples, and enslaved entire populations. At Kangra, he laid siege to Kangra Fort and forced Nagarkot to pay tribute, and did the same with Thatta.[15] He plundered the famous Nagarkot temples, carrying away idols and temple wealth to display in Delhi.

During his time Tatar Khan of Greater Khorasan attacked Punjab multiple times and during final battle in Gurdaspur his face was slashed by the sword given by Feroz Shah Tughlaq to Raja Kailash Pal of Mau-Paithan from Nagarkot region. Firuz Shah Tughlaq married off his daughter with Raja Kailash Pal, embraced him to Islam[citation needed] and sent the couple to rule Greater Khorasan, where eleven sons known by the caste of 'badpagey' were born to the queen.[18]

Rather than awarding position based on merit, Tughlaq allowed a noble's son to succeed to his father's position and jagir after his death.[19] The same was done in the army, where an old soldier could send his son, son-in-law or even his slave in his place. He increased the salary of the nobles. He stopped all kinds of harsh punishments such as cutting off hands. He also lowered the land taxes that Muhammad had raised. Tughlaq's reign has been described as the greatest age of corruption in medieval India: He once gave a golden tanka to a distraught soldier so that he could bribe the clerk to pass his sub-standard horse.[20]

Firoz Shah Tughlaq's reign was marked by both administrative reforms and aggressive religious policies aimed at consolidating Islamic rule in India. A devout Muslim, he is known for his efforts to enforce Sharia law, which included widespread persecution of Hindus and destruction of their religious institutions. According to his own memoir, Futuhat-i-Firoz Shahi, he took pride in forcing conversions and punishing those who resisted Islam.[21]

Firoz Shah implemented policies to marginalize non-Muslims, including the imposition of the jizya tax, a religious levy on Hindus and other non-Muslims. This tax was often so burdensome that it pushed many to convert to Islam. He actively targeted Hindu practices he deemed un-Islamic, such as sati (widow self-immolation), not as a reformer but to exert control. Public worship and celebrations of Hindu festivals like Holi and Diwali were banned during his rule.

In addition to military campaigns, Firoz Shah institutionalized forced conversions. His army often gave defeated Hindus a choice between death and conversion to Islam. He boasted of enslaving thousands of Hindus during his campaigns, using them for labor on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals, forts, and palaces.

Despite his achievements in administration and infrastructure development, such as irrigation systems and urban planning, Firoz Shah Tughlaq's legacy remains tainted by his policies of religious intolerance and systematic persecution of Hindus. His rule is often remembered as one of repression, marked by destruction and forced submission of non-Muslim communities.

Infrastructure and education

Tughlaq instituted economic policies to increase the material welfare of his people. Many rest houses (sarai), gardens and tombs (Tughluq tombs) were built. A number of madrasas (Islamic religious schools) were opened to encourage the religious education of Muslims. He set up hospitals for the free treatment of the poor and encouraged physicians in the development of Unani medicine.[22] He provided money for the marriage of girls belonging to poor families under the department of Diwan-i-khairat. He commissioned many public buildings in Delhi. He built Firoz Shah Palace Complex at Hisar in 1354 CE, over 300 villages and dug five major canals, including the renovation of Prithviraj Chauhan era Western Yamuna Canal, for irrigation bringing more land under cultivation for growing grain and fruit. For day-to-day administration, Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq heavily depended on Malik Maqbul, previously commander of Warangal fort, who was captured and converted to Islam.[23] When Tughlaq was away on a campaign to Sind and Gujarat for six months and no news was available about his whereabouts Maqbul ably protected Delhi.[24] He was the most highly favoured among the significant number of the nobles in Tughlaq's court and retained the trust of the sultan.[25] Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq used to call Maqbul as 'brother'. The sultan remarked that Khan-i-Jahan (Malik Maqbul) was the real ruler of Delhi.[26]

Hindu religious works were translated from Sanskrit to Persian and Arabic.[27] He had a large personal library of manuscripts in Persian, Arabic and other languages. He brought 2 Ashokan Pillars from Meerut, and Topra near Radaur in Yamunanagar district of Haryana, carefully cut and wrapped in silk, to Delhi in bullock cart trains. He re-erected one of them on the roof of his palace at Firuz Shah Kotla.[27]

Transfer of capital was the highlight of his reign. When the Qutb Minar was struck by lightning in 1368 AD, knocking off its top storey, he replaced them with the existing two floors, faced with red sandstone and white marble. One of his hunting lodges, Shikargah, also known as Kushak Mahal, is situated within the Teen Murti Bhavan complex, Delhi. The nearby Kushak Road is named after it, as is the Tughlaq Road further on.[28][29]

Legacy

His eldest son, Fateh Khan, died in 1376. He then abdicated in August 1387 and made his other son, Prince Muhammad, king. A slave rebellion forced him to confer the royal title to his grandson, Tughluq Khan.[15]

Tughlaq's death led to a war of succession coupled with nobles rebelling to set up independent states. His lenient attitude had strengthened the nobles, thus weakening his position. His successor Ghiyas-ud-Din Tughlaq II could not control the slaves or the nobles. The army had become weak and the empire had shrunk in size. Ten years after his death, Timur's invasion devastated Delhi. His tomb is located in Hauz Khas (New Delhi), close to the tank built by Alauddin Khalji. Attached to the tomb is a madrasa built by Firuz Shah in 1352–53.

Coin gallery

- Gold tanka of Firuz Shah

- Jital of 40 Rati

- Billon Tanka of Hazrat Dehli Dated AH 771

- Coin of 32 Rati

- Jital of 40 Rati

- Jital of 40 Rati

- Jital of Firoz Shah

References

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1994) [1984]. A History of Jaipur (Reprinted, revised ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 37. ISBN 978-8-12500-333-5.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (16 October 2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- ^ Tughlaq Shahi Kings of Delhi: Chart The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, v. 2, p. 369..

- ^ Banerjee, Anil Chandra (1983). A New History Of Medieval India. Delhi: S Chand & Company. pp. 61–62.

- ^ Peter Jackson (1999). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. p. 288. ISBN 9780521543293.

- ^ Blunt, Sir Edward (2010). The Caste System of Northern India. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8205-495-0.

- ^ Phadke, H. A. (1990). Haryana, Ancient and Medieval. Harman Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-85151-34-2.

- ^ Allapichai, A. M. (1973). Just a Peep Into the Muslim Mind.

- ^ Ahmad, Manazir (1978). Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq, 1351-1388 A.D. Chugh Publications.

- ^ Sinha, Narendra Krishna; Ray, Nisith Ranjan (1973). A History of India. Orient Longman.

- ^ Savarkar, Veer (1 January 2020). Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History: Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History: Veer Savarkar's Historical Masterpiece. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-93-5322-097-6.

- ^ Kishore, Kunal (1 January 2016). Ayodhya Revisited: AYODHYA REVISITED by KUNAL KISHORE: Revisiting the Ayodhya Issue. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8430-357-5.

- ^ Tughlaq, Firoz Shah (1949). Futūḥāt-i Fīrūz Shāhī (Reprinted by Aligarh Muslim University ed.). OCLC 45078860.

- ^ See Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad (1974). "The Futuhat-i-Firuz Shahi as a medieval inscription". Proceedings of the Seminar on Medieval Inscriptions (6–8th Feb. 1970). Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh: Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University. pp. 28–33. OCLC 3870911. and Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad (1983). On History and Historians of Medieval India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 205–210. OCLC 10349790.

- ^ a b c Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 97–100. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ "West Gate of Firoz Shah Kotla". British Library. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. pp. 67–76. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

- ^ Pathania, Raghunath Singh (1904). Twarikye Rajghrane Pathania. English version, 2004 Language & Culture Department Himachal Pradesh Govt.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1999). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-521-40477-8.

- ^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. p. 75. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

- ^ Tughlaq, Firoz Shah. Futuhat-i-Firoz Shahi. Translated by Elliot, H. M., and John Dowson, in The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, Vol. 3, Trübner & Co., 1871, pp. 380–394.

- ^ Tibb Firoz Shahi (1990) by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Department of History of Medicine and Science, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, 79pp

- ^ Ahmend, Manazir (1978). Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq, 1351–1388 A.D. Allahabad: Chugh Publications. pp. 46, 95. OCLC 5220076.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (1998). A History of India. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 0-415-15482-0.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1999). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-521-40477-8.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2007). Medieval India; From Sultanat to the Mughals. Har Anand Publications. p. 122. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- ^ a b Thapar, Romilla (1967). Medieval India. NCERT. p. 38. ISBN 81-7450-359-5.

- ^ "Indian cavalry's victorious trysts with India's history". Asian Age. 6 December 2011. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "King's resort in the wild". Hindustan Times. 4 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.