Firing pin

A firing pin or striker is a part of the firing mechanism of a firearm that impacts the primer in the base of a cartridge and causes it to fire. In firearms terminology, a striker is a particular type of firing pin where a compressed spring acts directly on the firing pin to provide the impact force rather than it being struck by a hammer.

The terms may also be used for a component of equipment or a device which has a similar function. Such equipment or devices include: artillery, munitions and pyrotechnics.

Firearms

The typical firing pin is a thin, simple rod with a hardened, rounded tip that strikes and crushes the primer. The rounded end ensures the primer is indented rather than pierced (to contain propellant gasses). It sits within a hole through the breechblock and is struck by the hammer when the trigger is "pulled". A light firing-pin spring is often used to keep the firing pin rearward. It may be termed a firing-pin return spring, since it returns it to the unfired position. In semi-automatic firearms, this prevents premature firing from the inertia of the firing pin as the breech mechanism closes in the reloading part of the firing cycle. Firing pins of this type are often too short to contact the primer when the hammer is resting against it. This is a safety measure to prevent discharge from external forces such as a drop. Firing relies upon the transfer of momentum from the hammer to give the firing pin sufficient impact energy to cause firing.

Type of cartridge

The two main types of metallic cartridges used in modern firearms are centerfire and rimfire. In centerfire cartridges, the primer is located in the center of the base of the cartridge. Firing pins for centerfire cartridges usually have a round cross-section and their movement is usually through a hole in the breechblock along the axis of the center of the barrel's bore.

Rimfire cartridges however, must be struck on the base about the rim of the cartridge. While rimfire firearms may use a firing pin with a round cross-section, it is common for them to be flat, with a square or rectangular cross-section and a blunt chisel point. Flat firing pins can be stamped from flat metal stock and usually operate in a slot cut in the breechblock (rather than a hole) that is parallel but offset from the centerline of the barrel. These production methods are generally simpler and reduce production costs. It is generally recommended not to excessively "dry fire" rimfire firearms (ie firing without a chambered round) as it is possible for the firing pin to strike the face of the camber and deform it or damage the firing pin.

Historical cartridges

In 1808 by the Swiss gunsmith Jean Samuel Pauly in association with French gunsmith François Prélat created the first cartridges to integrate a primer and be self-contained. The paper cartridge used a metal base with a through-hole coated in a percussive priming compound. Pauly also developed a breech-loading shotgun for his cartridge, using a firing pin and external hammer.[1]

The Dreyse needle gun of 1836 uses a paper cartridge with a priming as part of a sabot which cradles the projectile and is forward of the propelling charge. The needle-like firing pin projects from the bolt-face and pierces the cartridge when the breech is closed. On firing, the spring-loaded needle strikes the priming in the sabot. Unlike Pauly's cartridge, which was not widely accepted, Dreyse's rifle was adopted by Prussia as its infantry service rifle. It was the first military breechloader to use a self-contained cartridge and consequently, the first to employ a firing pin.[2][3]

The pinfire cartridge patented in 1835, uses a metallic cartridge with an integrated firing pin located radially near the base of the cartridge.[4] The pin needs to be aligned with a corresponding slot in the chamber; a disadvantage compared with rimfire and centerfire cartridges that followed and that are also safer.[2][5]

Side-lock hammers

Early rifle designs that fired metallic cartridges typically used a side-lock mechanism, with the hammer mounted to one side rather than inline with the axis of the barrel. In the trapdoor Springfield Model 1865 (and similar) the rear of the firing pin tube within the breechblock is angled away from the centerline of the barrel toward the hammer.[6] The Sharps rifle uses a firing pin block to solve this alignment problem. The block sits within a recess in the breechblock. When struck by the hammer, the whole block is propelled forward. That part of the block with the firing pin sits on the centerline of the barrel and strikes the primer.[7][8][9]

Fixed firing pins

Many revolvers use a firing pin that is fixed to the hammer. Simple blowback sub-machine guns that fire from the open-bolt position often have a fixed firing pin that protrudes from the face of the bolt. As the bolt fully closes on the breech the primer of the newly chambered round is struck, causing the cartridge to fire. The Owen and F1 submachine gun are examples that use bolt-face fixed firing-pins. Some mortars use a fixed firing pin mounted in the breech plug. When a mortar round is dropped down the barrel, a primer in the base of the mortar round strikes the firing pin and ignites the propelling charge.[10]

Floating firing pins

In firearms terminology, a floating firing pin is one which is unrestricted by a firing-pin return spring or similar. While it will be captive and unable to simply fall out, either forward or backward, it is otherwise free to slide within these stops. The trapdoor Springfield Model 1865 is an example of a floating firing pin.[11]

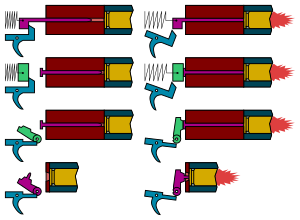

Striker

Hammer-operated firing mechanisms use a relatively light firing pin and rely on a transfer of momentum received from a spring-loaded hammer, in the same fashion as a punch or chisel relays the blow from a mallet. In firearms terminology, a striker (or striker mechanism) derives the impact force to strike the primer from a spring acting directly upon the firing pin – similar to a crossbow, where the striker (firing pin) is like the crossbow bolt (arrow). A striker mechanism is very common in bolt-action firearms but not to the exclusion of hammer-operated mechanisms. It is also found in other actions where the breechblock reciprocates directly inline with the axis of the barrel.

A striker mechanism will consist of the striker spring (firing spring) and the striker. The striker spring is a relatively strong spring sufficient to initiate firing. A typical striker consists of a narrow striking point, a heavier section that acts as a spring guide for the striker spring, a shoulder to restrain the spring, and a catch piece which is engaged by the trigger sear to hold the spring under tension when "cocked" and ready to fire. The striker spring is compressed between the striker's shoulder and the rear of the breechblock. A striker may be assembled from several component; however, the stored energy in the striker spring is transferred directly to the striker and then to the primer without any intermediate transfer of energy or momentum. As striker mechanisms combine both functions of hammer and firing pin in one piece, they are generally considered to be mechanically simpler but are more robust in construction than a typical firing pin.[12]

Many small-caliber rimfire bolt-action rifles and some centerfire automatic weapons (e. g., vz. 58) may appear to have a striker-operated firing mechanism but are actually a type of linear hammer. The hammer can be likened to that of a pile driver and is mainly contained within the bolt. It is much like the striker already described except that the "hammer" upon which the firing spring acts and the firing pin are separate units. Confusingly, parts lists will often refer to this type of hammer as a "striker".[13]

Striker-fired (or similar) bolt action firearms may be classified as cock-on-close or cock-on-open.

Cock-on-close

When the breech is opened and retracted rearward, the striker is also carried rearward so that the striker catch passes over the trigger sear. When the bolt is pushed forward to close the breech, the striker catch is held by the trigger sear. The firer must close the bolt with sufficient force to overcome the force exerted by the cocking spring. Notably, the Lee–Enfield and Belgian Mauser cock on closing as do many small-caliber rimfire bolt-action rifles.

Cock-on-open

The breech of a bolt action rifle is opened by first rotating the bolt handle. In cock-on-open operation, this rotation acts on a cam (similar to the action of a screw thread) which retracts the striker, compressing the cocking spring and holding it there. When the cocking handle is rotated closed, the cocking cam disengages but the striker is retained in the cocked position by the trigger sear.

Introduced in the Mauser Model 1871, it significantly reduced the risk of accidental discharge upon closing.[14] The system of operation was widely adopted and is used almost exclusively in modern centerfire rifle designs. The Mauser Gewehr 98, the Mosin–Nagant and M1903 Springfield are examples of service rifles using this type of operation.

Other applications

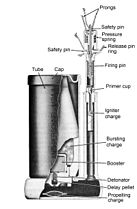

Modern era guns in general (and not just firearms) use a firing pin of some description to initiate firing. Mechanical contact fuzes in explosive ordnance will employ a firing pin or striker to initiate detonation. Such devices include: artillery projectiles, aerial bombs and land mines. In landmines, non-metallic firing pins, made from ceramics for example, may be used to minimise their magnetic signature.

The M127A1 signal rocket (and other similar flares) have a primer in the base of the disposable launch tube. The cap contains a fixed firing-pin inside. The flare is fired by placing the cap over the base and striking it by hand.[15]

Hand grenades of the type that use a safety lever (such as the M26 grenade) use a striker that is similar to the classic spring-loaded mousetrap. It is held under tension until the lever is released and then flips over to strike the primer cap. Some chemical oxygen generators use a primer and mousetrap type striker to initiate the chemical reaction.

Images

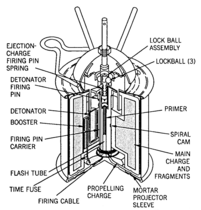

- Cutaway view of a Russian F1 fragmentation grenade showing firing pin

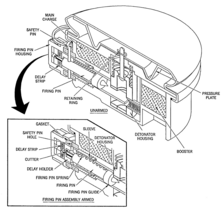

- Cutaway view of an M4 anti-tank mine showing integral firing pin

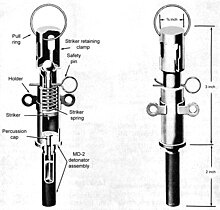

- PM-79 antipersonnel mine

- USSR boobytrap firing device—pressure fuze: victim steps on loose floorboard with fuze concealed underneath.

- Cross-sectional view of a BLU-43 Dragontooth cluster munition showing firing pin, detonator and adjacent explosive booster charge

- Cross-sectional view of a Japanese Type 99 grenade showing firing pin.

- Cross-sectional view of the fuze fitted to a German S-mine

- Cross-sectional view of an American M2 mine

- Cut-away view of an M14 antipersonnel landmine

References

- ^ Wallace, James Smyth (2008). Chemical Analysis of Firearms, Ammunition, and Gunshot Residue. Taylor & Francis. pp. 24–26. ISBN 9781420069716. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b Wallace 2008.

- ^ Lewis, Berkeley R. (1972) "Small Arms Ammunition at the International Exposition Philadelphia, 1876" in Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology (11) Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, p. 5. Archived 19 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Early cartridge designs were a composite of metal and paper.

- ^ Kinard, Jeff (2004) Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, ABC-CLIO, p. 109 Archived 28 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "U.S. Military Sprinfield 1873". Numrich Gun Parts Corporation. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "1874 Sharps Rifle From Down Under Parts - Pedersoli". Cimarron Firearms. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "How to Repair the Firing Pin on an 1869 Sharps Rifle - Midway USA Gunsmithing". YouTube. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Sharps 1874 rifle: firing pin plate bug No 2". YouTube. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Other types of drop-fired mortar ammunition have an internal firing-pin and the breech plug is a flat "anvil". The base of the falling round, with its internal firing pin, strikes the anvil and fires the round.

- ^ "SAAMI Glossary, F". SAAMI. Archived from the original on 2008-01-31. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Charles E. Petty. "XD X-Deelicious!". American Cop. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Savage / Stevens / Springfield / Fox Rifles 83". Numrich Gun Parts Corporation. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ O'Connell, Robert (2002), Soul of the Sword: An Illustrated History of Weaponry and Warfare from Prehistory to the Present, Free Press, p. 199, ISBN 9780684844077

- ^ "Family of Handheld Signals". Project Manager Close Combat Systems. Retrieved 10 March 2022.