File:Maximum-sustainable-yield-of-fish-with-addition.png

Original file (5,230 × 4,910 pixels, file size: 624 KB, MIME type: image/png)

Summary

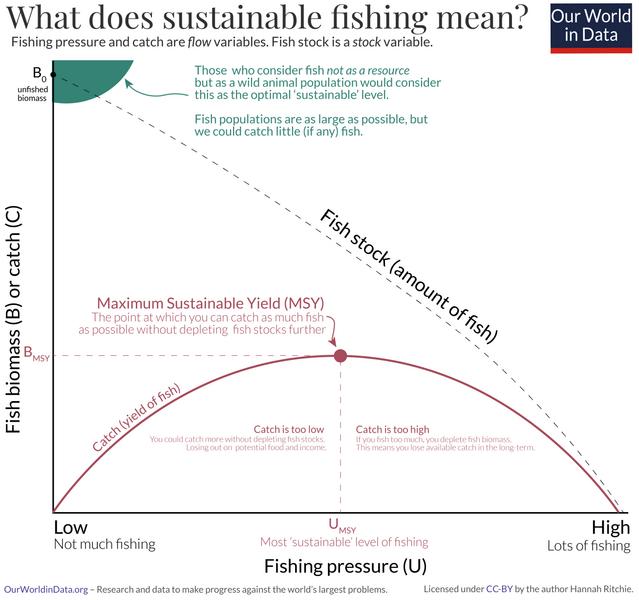

| DescriptionMaximum-sustainable-yield-of-fish-with-addition.png | English: What does sustainable fishing mean?

Is the global fishing industry sustainable? Which types of fish are we harvesting sustainably, and where are we overfishing? These are critical questions, but to answer them we need to first agree on what ‘sustainability’ actually means when it comes to fishing. One of the biggest conflicts I see is not actually about technical discussions of how much fish we catch, or whether populations are increasing or decreasing, but a larger ethical conflict in how we view fish. When we view fish through different lenses, these debates don’t get very far. One school of thought (often adopted by environmentalists, ecologists or animal welfare advocates) views fish as an animal in its own right; just as we view most other groups of animals. In the same way that most of us view elephants or monkeys. In this realm, our end goal is often to restore wild animal populations to as close to their pre-human levels as possible. The same would apply to fish: we should allow populations to increase back to their historical levels. Ultimately this means we should be catching very little (if any at all). The other school of thought views fish as a resource. Most of us eat fish; hundreds of millions rely on it for nutrition and income across the world. This is incompatible with restoring populations to their historical levels, because we can’t do that and catch lots of fish at the same time. Sustainability in this view means catching as much fish as possible without depleting fish populations any further. This ties in with the classic Brundtland definition of sustainability: “meeting the needs of the current generation, without sacrificing the needs of future generations”. We catch as much fish as possible to meet the needs of people alive today; but don’t take too much such that populations decline and this sacrifices catch for future generations. We can see these two schools of thought emerge in the typical diagram of sustainable fishing. On the x-axis we have fishing pressure; as we move towards the right we catch a larger proportion of the fish stock each year. Fishing pressure tells us about the fraction of the fish population that is caught in a given year. Note that this measure is a flow – it is an input variable that changes over time. On the y-axis we have fish biomass, given as two variables. First, we have the fish catch – shown as the red line. This, again, is a flow variable. Second, we have fish stocks. The fish stock is the total amount of fish left in the population. It, as we’d expect, is a stock variable. Let’s first look at the ‘stock’ line. This is the amount of fish we have in the oceans. It slopes downwards towards the right: if we fish very little then lots of fish are left in the ocean and as we increase fishing pressure, we deplete the amount of fish in our oceans. This makes sense. Our first school of thought – that fish are not a resource, but a wild animal population in their own right – suggests we should be aiming for the top-left corner. Fish populations are as close to pre-human levels as possible. To do this, we need to catch very little (if any) fish. Our second school of thought – that fish are a resource – would consider the optimal level to be the red dot. This is what is called the ‘maximum sustainable yield’. This is a key concept in fishery research and industry. It’s where we can catch as much fish as possible annually without depleting stocks any further. If you get greedy and catch more than this, then you deplete populations for future generations. If you catch too little then you’re sacrificing food and income for the current generation. Most fisheries are aiming for this sweet spot: catching not too much; not too little; just right. The tension between these two schools becomes obvious. The optimal outcome is completely different. When a fish stock is at its ‘maximum sustainable yield’ it’s around half of its original, virgin biomass.9 This level can vary between fish populations but is typically in the range of 37% to 50% of its pre-fishing levels. In other words: if you view fish as a resource you probably want fish populations to be less than half the size of pre-fishing size. Most of the research, industry, and policymaking is geared towards the second school: viewing fish as a resource. Therefore much of our work on fish on Our World in Data will explore these concepts, and explain what the research and data tells us about fish stocks, catch and the sustainability of fishing across the world. But we will also offer the perspective of the first school, by looking at how fish populations have changed from their pre-human levels. |

| Date | October 2021 |

| Source | https://ourworldindata.org/fish-and-overfishing |

| Author | Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser |

Licensing

- You are free:

- to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work

- to remix – to adapt the work

- Under the following conditions:

- attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- share alike – If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same or compatible license as the original.

Captions

Items portrayed in this file

depicts

copyright status

copyrighted

copyright license

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 14:00, 21 July 2022 |  | 5,230 × 4,910 (624 KB) | PJ Geest | Uploaded a work by Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser from https://ourworldindata.org/fish-and-overfishing with UploadWizard |

File usage

The following 2 pages use this file:

Metadata

This file contains additional information, probably added from the digital camera or scanner used to create or digitize it.

If the file has been modified from its original state, some details may not fully reflect the modified file.

| Horizontal resolution | 118.11 dpc |

|---|---|

| Vertical resolution | 118.11 dpc |