Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 1478 – 1557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first few years after Christopher Columbus became the first European to arrive at the islands in 1492. Oviedo's chronicle Historia general de las Indias, published in 1535 to expand on his 1526 summary La Natural hystoria de las Indias (collectively reprinted, three centuries after his death, as Historia general y natural de las Indias), forms one of the few primary sources about it. Portions of the original text were widely read in the 16th century in Spanish, English, Italian and French editions, and introduced Europeans to the hammock, the pineapple, and tobacco as well as creating influential representations of the colonized peoples of the region.

Early life

Oviedo was born in Madrid of an Asturian lineage and educated in the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. He was a page to their son, the Infante John, Prince of Asturias, from about the age of fourteen until the Prince's death in 1497, and then Oviedo went to Italy for three years before returning to Spain as a bureaucrat to the emerging Castilian imperial project. Oviedo married first Margarite de Vergara, who died in childbirth, and then Isabel de Aguilar. Isabel and their multiple children later died within several years of joining Oviedo in America.[1]

Caribbean

In 1514 Oviedo was appointed supervisor of gold smelting at Santo Domingo, and on his return to Spain in 1523 was appointed historian of the West Indies. He paid five more visits to the Americas before his death, in Valladolid in 1557.[2] At one point he was placed in charge of the Fortaleza Ozama, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where there is a large statue of him, a gift to that country from a King of Spain.

Works

Oviedo's first literary work was a chivalric romance entitled, Libro del muy esforzado e invencible caballero Don Claribalte (Book of the very striving and invincible knight Don Claribalte). It was published in 1519 in Valencia by Juan Viñao, one of the prominent printers of that time. In the foreword, dedicated to Ferdinand of Aragón, Duke of Calabria (not to be confused with the King Ferdinand II of Aragon), Oviedo relates that the work had been conceived and written while he was in Santo Domingo. Therefore, it seems that this was the first literary work created in the New World.[3]

Oviedo later wrote two extensive works of permanent value, which for the most part were not published until three centuries after his death: La historia general y natural de las Indias and Las Quinquagenas de la nobleza de España. The Quinquagenas is a collection of quaint, moralizing anecdotes in which Oviedo indulges in much lively gossip concerning eminent contemporaries. It was first published at Madrid in 1880, edited by Vicente de la Fuente.[2]

General History of the Indies

Oviedo first published a smaller work, La Natural hystoria de las Indias, which was published at his expense on 15 February 1526 in Toledo.[4] This is often described as the Sumario.[1] An Italian translation of this appeared in Venice in 1534, with French editions from 1545 and English ones from 1555, although there was no second Spanish edition until 1749. This 108 page work contained only a few illustrations, although it did include one of a hammock.[4] In 1535 the first part of the longer and more fully illustrated Historia general de las Indias was printed in Seville, and Oviedo had outlined two subsequent parts. He continued to work in both Santo Domingo and Spain on subsequent parts and to revise the first part until his death in 1557.[5] That year, Fernández de Cordoba published the entirety of Historia General's first volume in Valladolid, as well as the first two-thirds of the second volume. The remainder, however, languished in Oviedo's absence.[6] The manuscript was kept in the Monserrate monastery for many years and then the Royal Academy of History. Surviving portions were used by José Amador de los Ríos in preparing an 1851 edition titled Natural y General Hystoria de las Indias.[5][7] Although some portions were known to be missing by 1780, further large portions of the manuscript which were present then are no longer in Madrid. A paper by Jesús Carrillo in the Huntington Library Quarterly described the circumstances of the disposal as 'unknown'.[5] Some were sold, by a London bookseller, Maggs to Henry E. Huntington in 1926 and are now held in the Huntington Library.[8] A transcription of part of the manuscript was made in Seville by Andres Gasco before 1566 and two of the three volumes of this transcription are held in the library of the Royal Palace of Madrid.[5]

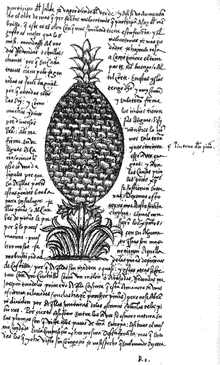

The Historia, though written in a diffuse style, furnishes a mass of information collected at first hand. Las Casas, the fellow contemporary chronicler of the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean, denounced Oviedo as "one of the greatest tyrants, thieves, and destroyers of the Indies, whose Historia contains almost as many lies as pages".[10] The incomplete Seville edition was widely read in the English and French versions published by Eden and Poleur, respectively, in 1555 and 1556.[2] It is through the Historia that Europeans came to learn about the hammock, pineapple, tobacco, and barbecue, among other things used by the Native Americans that he encountered. The first illustration of a pineapple is credited to him.[11]

Extinct animals

In zoology, the General History of the Indies is of particular interest for its descriptions of Hispaniolan animals, including some that became extinct between Oviedo's time and the development of the modern science from Linnaeus and Cuvier. The only land mammals of the island according to Oviedo, besides rats and mice (which Oviedo believed native, but were introduced accidentally by Europeans), were:

- The hutia: a grizzled-gray (pardo gris), four-legged animal resembling a rabbit, but smaller, with smaller ears and a rat-like tail. Hunted with dogs by natives and Spaniards alike, it was "no longer found except very rarely". Gerrit Smith Miller Jr. identified this animal as either the living Hispaniolan hutia or one of the extinct Isolobodon hutias.[12]

- The quemi: similar to the hutia in color and appearance, but much larger, like a medium hound. It was also eaten, and Oviedo believed it already extinct. Miller identified it with a large subfossil rodent found in caverns and archaeological middens, which he named Quemisia.[12]

- The mohuy: Also similar to the hutia but smaller and paler, and with denser and coarser hair, which was very pointed and stood erect on its back. Its meat was considered the best by people who had eaten it and was highly esteemed by the caciques of the island. Miller identified this with the Hispaniolan edible rat, an extinct rodent commonly found in middens, on the basis of the size and erect hair reported by Oviedo (similar to the spiny rats of the family Echimyidae). He gave it the specific name voratus, meaning "devoured".[12]

- The cori: the domestic guinea pig, raised for food in captivity.[12] Actually introduced from South America by the natives prior to Spanish contact.[13]

- The "mute dog" (perro mudo, literally "mute dog", translated as "dumb dog" by Miller): a Native American dog that could not bark, had erect ears, and all kinds of hair length and colorations found in domestic dogs. It was raised by the natives in their houses and used to hunt hutias, though European dogs were more effective. It was extinct on Hispaniola at the time of Oviedo's writing, but he saw similar dogs in native settlements of other islands and the American mainland (in what is now Nicaragua).[12]

Notes

- ^ a b Myers, Kathleen Ann (2007). Fernández de Oviedo's chronicle of America : a new history for a New World. Scott, Nina M. (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-79502-0. OCLC 608836622.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo Fernández de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 391.

- ^ Agustín G. de Amezúa. Introduction to the facsimile reprint of Libro de Claribalte by the Spanish Royal Academy, Madrid, 1956

- ^ a b Stoudemire, Sterling A. (1969). De La Natural Hystoria De Las Indias. University of North Caroline.

- ^ a b c d Carrillo, Jesús (2002). "The 'Historia General y Natural de las Indias' by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo". Huntington Library Quarterly. 65 (3/4): 321–344. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817978.

- ^ Dille, G. F. (2006). "Introduction". Writing from the edge of the world: The memoirs of Darién, 1514-1527. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-8173-5339-1.

- ^ Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo (1851) [1535]. José Amador de los Ríos (ed.). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Madrid: La Real Academia de la Historia. Retrieved 2020-07-15 – via Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library.

- ^ "Card catalog entry b180028". The Huntington. Archived 29 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Beauman, Fran. (2005-12-27). The pineapple : king of fruits. London. ISBN 0-7011-7699-7. OCLC 61440838.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Liévano Aguirre, Indalecio. 2002. Los grandes conflictos sociales y económicos de nuestra historia. Volumes 3–4. Bogotá: Intermedio. page 84.

- ^ Lee, Alexander (2019). "The History of the Barbecue". History Today. 69 (8).

- ^ a b c d e Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

- ^ MacPhee, R. D. E. (2009). Insulae infortunatae: establishing a chronology for Late Quaternary mammal extinctions in the West Indies. In American megafaunal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene (pp. 169–193). Springer, Dordrecht.

Further reading

- Arocena, Luis A. (1989). "Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés". Latin American Writers, vol. 1. New York: Scribner. pp. 10–15.

- Carrillo, Jesús (2002). "The "Historia General y Natural de las Indias" by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo". Huntington Library Quarterly. 65 (3/4): 321–344. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817978.

- Meyers, Kathleen Ann (2007). "Gonzalo, Fernández de Oviedo". The Oxford Companion to World Exploration. Oxford University Press.

- Pérez de Tudela y Bueso, Juan. "Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés". Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish).

- Turner, Daymond (1985). "Forgotten Treasure from the Indies: The Illustrations and Drawings of Fernández de Oviedo". Huntington Library Quarterly. 48 (1): 1–46. doi:10.2307/3817095. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817095.