Feminists and the Spanish Civil War

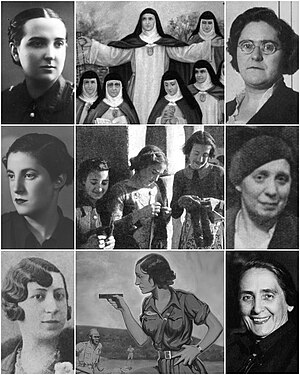

| Part of a series on |

| Women in the Spanish Civil War |

|---|

|

|

|

Feminists were involved in the Spanish Civil War, although the conditions underlying their involvement pre-dated the Second Republic.

The feminist movement in Spain started during the 19th century, aiming to secure rights for women and striving for more than women could expect from their place in the home. Supported by a number of Spanish writers, it was one of the first feminist movements to inject anarchism into feminist thinking. In contrast to feminism developments elsewhere, many Spanish feminists sought to realize their goals in this period through the education of women. When political activity took place to further feminist goals and the more general aspirations of groups, it tended to be spontaneous and easily dismissed by men. Margarita Nelken, María Martínez Sierra and Carmen de Burgos were all important pre-Republic writers who influenced feminist thinking inside Spain.

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera provided more opportunities for women to be engaged politically, with the appointment of women to the Congreso de los Diputados. Thought they were not successful, the first steps were also taken towards women's suffrage. Feminine independence, principally organized in Madrid around the Lyceum Club, was condemned by members of the Catholic Church and viewed as scandalous. Women continued to be locked out of political and labor organizations such as the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo.

Feminism in the Republican and Civil War eras was typically about "dual militancy" and was greatly influenced by anarchism and by an understanding of potential societal developments. Yet increased women's emancipation was constantly threatened by leftist attempts to prevent their opponents from taking power. Most of the advances gained, including the right to vote, civil marriage, abortion and access to birth control would be lost before the Second Republic fell. Clara Campoamor Rodríguez was the most important proponent of women's suffrage in this period.

During the Civil War, mainstream leftist feminism often took on an individualistic approach to addressing inequalities, with battles as to whether their autonomy should be personal or political. Mujeres Libres, founded by Lucia Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón in May 1936, became one of the most important organizations for feminists. Dolores Ibárruri earned herself the nickname La Pasionaria as she traveled the country to speak in opposition to Francoist forces, making her one of the most visible and important feminist voices.

Francisco Franco and his forces won the Civil War in 1939. Mainstream feminism subsequently disappeared from public discourse, largely being replaced publicly by an oppressive form of state-sponsored feminism that was no more than support for Spain's traditional gender roles that denied women personal and political autonomy. Traditional gender norms returned with force. Sanctioned feminist writing in the post-war period stemmed largely from the works of aristocratic women such as María Lafitte, Countess of Campo Alanaga, and Lilí Álvarez. Works by Republican pre-war feminists like Rosa Chacel and María Zambrano, who continued to write in exile, saw their works smuggled into Spain. As a result, the contributions women and feminists had made during the Civil War were largely forgotten.

Prelude to the Second Republic (1800 - 1922)

"If it were necessary the quality of [skull's] volume to perform with equal power, the inferiority of women would be in all areas. Her senses would be clumsier, and in accordance to Fall's capacity categorization, her circumspection would be inferior as would her sense of location, her love of property, her sense of justice, her disposition for the arts, etc. ... But nothing like this transpires: Women in most abilities are equal to men and their intellectual differences begin where their different education starts. Indeed their teachers soon realize the differences between boys' and girls' talent, and if there is any it is in favor of girls, who are more docile and in general more precocious."

During the 1800s, the most important women advocating for women's rights in Spain were Teresa Claramunt and Teresa Mañé, both coming from the anarchist movement.[1] Ángeles López de Ayala y Molero founded Sociedad Progresiva Femenina in 1898, one of Spain's earliest feminist organizations alongside Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres de Barcelona which she had founded in 1892.[2] They built on ideas that were being developed by the North American feminists, Voltairine de Cleyre and Emma Goldman. Spanish women were among the first to inject anarchism into feminist thinking.[1]

The feminism of Spain in the period between 1900 and 1930 differed from similar movements in the United Kingdom and the United States. It also tended to come from a liberal or leftist perspective. Spanish feminist intellectuals in this period included the militant socialist María Cambrils, who published Feminismo socialista. They also included Clara Campoamor, Virginia González and Carmen de Burgos.[3] One of the more notable pre-Republic feminists was lawyer and prison reformer Concepción Arenal. She believed it was important for women to strive for more in life than what was to be found in the confines of the home.[4][5]

The feminist movement began to get traction in 1915, when the National Association of Spanish Women (ANME) first started to work together to address women's needs. ANME's early feminism was characterized by its right wing leanings, as a result of its being associated with Spain's upper classes.[6]

The Seccion Varia de Trabajadoras anarco-colectivistas de Sabadell was founded by Claramunt and other like-minded women in 1884. Working with Ateneo Obreros, the organizations sought to emancipate both men and women through education. It folded sometime before late 1885.[1]

Agrupación de Trabajadores was created as a labor organization in 1891 by Claramunt to support her feminist ideals, and soon organized public meetings. The organization argued that women were being doubly punished by society, as they were expected to work outside the home to provide for the family while at the same time having to meet all the domestic needs of the household. The organization was never particularly successful in its goals as many women in the workforce did not see a need for representation by a union.[6][1]

Belén Ságarra had been involved with the Sociedad Autónoma de Mujeres de Barcelona, an organization founded around 1891. She and Claramunt sought to create Associación Librepensadora de Mujeres. Ságarra was prevented from doing so after being arrested in 1896 for being anti-Christian and promoting free-thinking.[6][2]

Employment and labor organizations

While 17% of women worked in 1877, most were peasants who were involved in agriculture. Despite Spanish industrialization in Spain, including that of agriculture in the 1900s, restrictive gender norms meant only 9% of women were employed by 1930. This represented a drop of 12% or 0.5 million women in the workforce from 1877 to 1930.[7] Prostitution was legal in pre-Second Republic Spain, and poor, white women lived in fear of being trafficked as slaves.[3] By the 1900s, women could and did sometimes work in factory sweatshops, alongside young male workers.[3] Most women seeking employment worked in the homes of the more affluent.[3] These jobs paid so little that female workers often struggled to earn enough to feed themselves.[3] When women were involved in factory work in this period, they were often paid half the wage of their male counterparts.[7][3]

Despite the lack of presence in the workforce, women did engage in labor protests in specific industries where they were over represented. This included labor action in Madrid in 1830, where there were five days of rioting over wage reductions and unsafe working conditions by 3,000 female tobacco workers. Women tobacco workers were also the first to unionize, creating their first union in 1918. The union was successful in doubling wages for its workers in 1914 and 1920. It also successfully had workers wages tripled in 1930.[7][8] Their labor actions continued into the Second Republic.[8] Despite their involvement in organizing labor in tobacco, women were largely absent from late nineteenth century labor movements in Spain.[7] Although there were few opportunities for women, some did manage to get highly ranked government positions, though these were few and far between.[9]

Political activity

The nineteenth century saw for the first time the emergence of a true middle class in Spain. This precipitated internal questioning among the Spanish elite about social inequalities that had existed in Spain since the founding of the modern Spanish state when Isabella of Castille married Ferdinand of Aragon, solidifying Spanish territory under one government. These discussions would see the creation of the First Spanish Republic from 1873 to 1874.[3]

The Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE) was founded by persecuted Spanish intellectuals, catering to freethinkers in educational facilities outside government control. The ILE was important in forming ideologies leading to the creation of the Second Spanish Republic.[3] It was revolutionary in Spain in that it was one of the first organizations to recognize the potential of women, though this was still viewed as limited. To this end, ILE member Fernando de Castro, then dean of the Universidad de Madrid, created the "Sunday Lectures for the Education of Women" in 1868.[3]

Direct women's involvement

As women in the pre-Republican period were largely confined to domestic spheres, their political activity tended to be centered, though not always, around issues related to consumer activities. Women protested and rioted in this period over goods and services shortages, high rents and high prices of consumer goods. Their protests were designed to encourage the government to change its practices by addressing these issues.[7]

Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (Spanish: Partido Socialista Obrero Español) (PSOE) was founded in 1879 as primarily a labor movement organization. Its early pre-1900s membership was almost exclusively male, and they had no interest in women's issues or feminist goals.[7][3] The first women's group inside PSOE was not founded until 1902. It would not be the last. PSOE's women's groups remained small and subordinate to larger, male-dominated socialist groups.[10] The early 1900s, 1910s and 1920s also saw a growth of women in the workforce in sectors such as nursing and education. These women also joined unions.[10] During the 1920s and early 1930s, women became more involved with socialist movements. This did not translate into participation on the political side, as socialist political organizations were openly hostile to women and not interested in attracting their involvement.[7] When women did create socialist organizations, they were auxiliary to those dominated by men. This was the case for Group of Feminist Socialists of Madrid and Feminist Socialist Group. Unlike their anarchist peers, socialist women played much more passive roles. As a consequence, when the Civil War started, few socialist women headed to the front lines.[7][3] Prominent women socialists in this period included Matilde Huici, Matilde Cantos and Matilde de la Torre. Largely participating in women's caucuses, their advocacy was often ineffective in pressing for women's rights as their position inside the broader socialist party governance structure was very weak.[4]

Despite barriers for political participation, some anarchist women were politically engaged in this period despite gender tensions which served to limit their participation. One example of such tension occurred during the 1918 Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) Congress, where gender-based tensions among anarchists in Spain were visibly present. Men tried to use the Congress to assert their own power over women to set goals and policies that would have them dominate both the public and private sphere. This was in large part because male anarchists did not want to see a power dynamic change which would result in diminishing their own status.[7]

Few women were involved in the Communist Party of Spain (Spanish: Partido Comunista de España) (PCE), but Dolores Ibárruri joined by the early 1920s. An active participant in organizing labor strikes and a firm believer in women's rights, Ibárruri was elected to the PCE Central Committee in 1930. Two years later, she was the head of its Women's Commission.[11][12]

Prior to the Second Republic, PSOE recognized that women workers lacked a compensatory educational system and access to educational facilities equivalent to those of their male peers. Yet, despite this, they failed to offer any sort of comprehensive policy solution to the problem and were unwilling to advocate strongly on the need to address women's education. The extent of their activism for women's education were demands for integral education for men and women.[4] The Feminine Socialist Group of Madrid met in 1926 to discuss women's rights. Attendees included Victoria Kent and Clara Campoamor.[3]

Education

María de Maeztu was an early twentieth century Spanish feminist and pedagogist. She helped co-found the International Institute for Young Ladies in Spain in 1913 as part of larger collaborative efforts. Two years later, she founded the Residence for Young Ladies. Continuing to push for women's education in pre-Republican days, she founded the Lyceum Club in 1926 with cooperation for the International Institute for Young Women. The club was the first of its kind in Madrid. It would see its ranks include other important Spanish feminists of its day, including Isabel Oyarzabal de Palencia and Victoria Kent. It had over 500 members by 1930, and included a branch in Barcelona.[3]

Women's media and writing

Margarita Nelken, María Martínez Sierra, Carmen de Burgos and Rosalía de Castro were all important pre-Republic writers who influenced feminist thinking inside Spain.[13][8][14][15]

Carmen de Burgos was not primarily known for her feminist writings in the pre-Republican period but rather for writing popular novellas. Despite that, her La mujer moderna y sus derechos in 1927 was one of the most important feminist works of its time. As a feminist, she started her writing career in the early 1920s as a relatively moderate feminist. Having written for various liberal and progressive newspapers from the 1900s to 1920s, it was only as time passed during the latter part of the decade that she became more radical and part of the First Wave Feminism. As a feminist, she advocated for reforms to Spain's legal system, including legalizing divorce and women's suffrage.[16]

María Martínez Sierra wrote under the name Gregorio Martínez Sierra, publishing a series of four essays using her husband's name during the period from 19116 to 1932. These included Cartas a las mujeres de España, Feminismo, femindidad, españolismo, La mujer moderna, and Nuevas cartas a las mujeres de España. Not until the death of her husband in 1947 did María de la O Lejárraga claim authorship of these writings and admit to intentionally trying to use a masculine name in order to gain credibility. The feminism she espoused in these letters was a paradox given the impression of male authorship. Her wider body of feminist work also sat outside the feminism being developed by Anglo women in North America and Great Britain, but was well received inside Spain as her plays were performed in Madrid's theaters. One of her major contributions was in changing the medium from which feminist themes were shared, her primary themes being the problem of subordination of women.[14]

La condición social de la mujer en España was the most notable work of Margarita Nelken in this period. Published in 1919, it was revolutionary in Spanish feminism to the extent that it went beyond describing the problems of women to proscribing solutions, and advocating for changes in women's relationships to groups such as working and middle-class men, women of different classes, and institutions like the Catholic Church. Writing from a socialist perspective, her feminist works sought to address the conflict between the roles women were expected to maintain in a patriarchal society.[14]

Rosalía de Castro, born in 1837 in Santiago de Compostela, wrote novels from a female point of view that addressed suffering at the hands of men, with this violence supported by the patriarchal society in which it took place. Her work took a more realistic approach to the condition of women, and their problems in overcoming social injustices that chained them to a certain way of life. She played an important role in calling for assistance for women seeking justice for the violence they suffered.[15]

Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1930)

The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera started in 1923 and continued until 1929, leading to elections being called for June 1931.[1]

This period saw few feminist events in Spain. When women did organize, men viewed their activities as a joke. Feminine independence, principally organized in Madrid around the Lyceum Club, was condemned by members of the Catholic Church and viewed as scandalous. It was viewed by some men as threatening to the status quo.[3] Feminists in the dictatorship period were often focused on restrained but determined efforts to be nonconformist in their approach to womanhood. Most of their activity was devoted towards creating fictional works as a form of social criticism.[3] Other feminist organizations also existed by 1920, though they were much less visible and less successful in their goals. They included the Future and Feminine Progressive in Barcelona, the Concepción Arenal Society in Valencia and the Feminine Social Action Group in Madrid. Most members came from middle-class backgrounds, and consequently did not represent the broader spectrum of women in Spain.[3] The Feminine Socialist Group of Madrid met in 1926 to discuss women's rights. Attendees included Victoria Kent and Clara Campoamor.[3]

In the lead-up to the founding of the Second Republic and the Civil War, many middle-class and upper-class women who became feminists did so as a result of boarding school educations resulting in parents unable to guide the evolution of their political thoughts, fathers encouraging daughters towards political thinking, or being indoctrinated in classes essentially aimed at reinforcing societal gender norms. Left-leaning families were more likely to see their ideas manifested by their daughters as feminists as a result of their active influence. Right-leaning families were more likely to see their daughters become feminists through rigid gender norms resulting in a family break.[3]

Political activity

When political activity was triggered by women in the pre-Republican period, it was often spontaneous. Women were often ignored by left-wing male political leaders. Despite this, their riots and protests represented increasing political awareness of the need for women to be more active in social and political spheres in order to bring about improvements in their own lives and those of other women.[7]

Middle-class women in urban areas, freed from labor in the home, started to lobby for changes to improve their own lives, calling for changes in divorce laws, better education and equal pay.[17] When politicians were faced with these demands, they often labeled them "women's issues".[17] No serious reforms could be achieved under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship.[17]

The 1927-1929 session of the Cortes Generales began the process of drafting a new Spanish constitution that would have fully franchised women voters in its Article 55. The article was not approved. Nevertheless, women were eligible to serve in the national assembly in the Congreso de los Diputados, and 15 women were given seats on 10 October 1927. Thirteen were members of the National Life Activities Representatives (Spanish: Representantes de Actividades de la Vida Nacional). Another two were State Representatives (Spanish: Representantes del Estado). These women included María de Maeztu, Micaela Díaz and Concepción Loring. During the Congreso de los Diputados's inaugural session in 1927, the President of the Assembly specifically welcomed the new women, claiming their exclusion had been unjust.[18][19] Loring Heredia interrupted the proceedings and demanded an explanation from the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts on 23 November 1927, marking it the first time a woman had spoken from the Congress floor.[20][19]

Second Spanish Republic (1931 - 1937)

One of the most important aspects of the Second Republic for women is that they were formally allowed to enter the public sphere en masse.[21] The period also saw a number of rights available to women for the first time, including suffrage, divorce and access to higher education. These resulted from feminist activities that pre-dated the Second Republic and continued throughout its duration.[21]

Feminism in the Republican and Civil War eras was typically about "dual militancy" and was greatly influenced by anarchism and an understanding of the role feminism should play in society.[13] The Civil War would serve as a break point for feminist activity inside Spain. There would be little continuity in pre-war and post-war Spanish feminism.[13][4]

Elections in the Second Republic

The Spanish monarchy ended in 1931.[22] Following this and the end of the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the Second Republic was formed. The Second Republic had three elections before it was replaced by the Franco dictatorship.[22][3] They were held in 1931, 1933 and 1936.[3]

June 1931 Elections

Following the failure of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, Spain set about writing a constitution. The initial draft did not give women the right to vote, though it did give them the right to run for office on 8 May 1931 for the June elections.[17][23] Three women won seats in Spain's national congress, the Cortes, in the 1931 elections: Clara Campoamor Rodríguez, Victoria Kent Siano and Margarita Nelken y Mansbergen.[17][23][1]

Campoamor, in arguing for women's suffrage before the Cortes on 1 October 1931, stated that women were not being given the right to vote as a prize, but as a reward for fighting for the Republic. Women protested the war in Morocco, those in Zaragoza protested the war in Cuba while even larger numbers protested the closure of Ateneo de Madrid by the government of Primo de Rivera.[24] Campoamor also argued that women's inclusion was fundamental to saving the Republic by having a politically engaged populace, so that the errors of the French Republic would not be repeated.[24]

Kent, in contrast, received much more support from Spain's right, including Catholics and traditionalists, during this period of constitutional debate as she, alongside Nelken, opposed women's suffrage, believing women would vote along lines dictated by their husbands and the Roman Catholic Church. They also believed that most women were too illiterate to be informed voters, and their participation as electors would set back Republican goals and women's rights.[25][1] Kent and Campoamor became involved in a grand debate over the issue, receiving extensive press coverage of their arguments concerning women's suffrage.[25][1]

1933 Elections

For the first time, in 1933 women were permitted to vote in the national elections.[25] The victory of conservative factions in the 1933 elections was blamed on women and the way they had voted. They were viewed as being controlled by the Church.[3]

Campoamor, along with Kent, lost her seat in the Cortes following the 1933 elections.[3][25] The most active of the three women elected in 1931, she had been heckled in the congress during her two-year term for her support of divorce. She continued to serve in government with an appointment as head of Public Welfare later that year. However, she left her post in 1934, protesting the government's response to the 1934 Revolution of Asturias.[3]

Nelken faced similar problems in the Cortes. Her mother was French and her father was a German Jew. As a consequence, before she was allowed to sit in 1931, Nelken had to go through special bureaucratic procedures to insure she was a naturalized Spanish citizen. Her political interests were looked down upon by her male peers, including Prime Minister Manuel Azaña. Her feminist beliefs worried and threatened her male colleagues in the Cortes. Despite this, she was re-elected in 1933, facing attacks in the media. She proved a constant irritant to male party members who sometimes resorted to racist attacks in the Cortes to quieten her down.[3] Still, she persevered, winning at the elections in 1931, 1933 and 1936. Disillusionment with the party led her to change membership to the Communist Party in 1937.[3]

February 1936 elections

The February 1936 elections saw the return of a leftist government. Together, the various left-wing groups formed the Popular Front. They replaced a repressive right-leaning government that had been in power for the two previous years.[26][27]

The Popular Front won elections in February 1936 on a progressive platform, promising major reforms to government. In response, even as the left began reform plans to undo conservative efforts from the previous government, the military began planning how to overthrow the new government.[7][27][1] The Popular Front, in contrast, refused to arm its own supporters, fearing they would fight against the Government.[1]

Feminist organizations

Female Republican Union

Clara Campoamor created the Female Republican Union (Unión Republicana de Mujeres) during the early part of the Second Republic.[6][28] The Female Republican Union was interested only in advocating for women's suffrage.[6][10] It was often polemicist in its opposition to Kent's group Foundation for Women, and its opposition to women's suffrage. They believed now was the time to act, and if they failed to act, there may never be time for women to be granted the right to vote.[28]

Foundation for Women

Victoria Kent and Margarita Nelken founded the Foundation for Women (Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Española) in 1918.[28][6] The Foundation for Women was a radical socialist organization at its inception, aligning itself with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party or PSOE. The organization opposed women's suffrage, even as its founders sat in the Cortes. The belief was if women were given the right to vote, most women would vote as instructed by their husbands and the Catholic Church. This would fundamentally damage the secular nature of the Second Republic, by bringing in a democratically elected right wing government.[6][10] They believed that it was better to address other issues facing women at the time and revisit the topic of women's suffrage later, when women were more educated and the right-wing threat was lessened.[28] Kent's views led to the biggest and most visible feminist conflict of her disagreement and public battles with Campoamor during the period.[6][28][10]

Political activity

The changing political landscape of the Second Republic meant that for the first time there was an environment in which women's political organizations could flourish.[6]

Women were also largely locked out of organized political groups in this period, even those claiming to be in favor of gender equity. Major trade unions at the time like the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and the CNT ignored specific needs of women, including maternity leave, childcare provisions and equal pay; instead, they focused on general needs or the needs of the male workforces they represented.[7] The National Confederation of Labour (Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores or CNT) perpetuated gender inequality, paying its female employees less than men in comparable positions.[29] Only 4% of UGT's membership was female by 1932.[7]

One of the greatest challenges faced by leftist women was Marxism, prioritizing the issue of class equality over gender issues. For anarchists, trade unionists, and communist and socialist women, this often resulted in the male leadership dismissing women's needs. Women were not permitted to participate in their agenda as their needs did not directly relate to the class struggle.[10][1] Some leftist men, both in political and labor organizations, also resented women entering the workforce, viewing their lower wages as an incentive for employers to reduce wages for men.[1]

Despite differences in ideology, communist, Republican and socialist women would meet for discussions about the political issues of the day. They also worked to mobilize women en masse to protest issues they felt were important. One such mobilization occurred in 1934, when the Republican government considered calling up its reserves for military action in Morocco. Within hours of the news hitting the streets, Communist, Republican and Socialist women had organized a women's march in Madrid to protest the proposed actio. Many were arrested, taken to police headquarters and later released.[8]

Anarchists

On the whole, the anarchist movement's male leadership deliberately excluded women and discouraged them from seeking leadership positions.[7][13][30][22] Women were effectively locked out of the two largest anarchist organizations, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI).[22][1]

CNT total membership ranks were over 850,000 by July 1935, and were organized by region and sector of employment.[22] Despite large numbers of women members, CNT ignored specific needs of women, including maternity leave, childcare provisions and equal pay; instead they focused on general needs or needs of men in the workforces they represented.[7] The CNT also perpetuated gender inequality, paying its female employees less than men in comparable positions.[29]

FAI was created by more militant members of CNT.[22][1] Women found it difficult to join the organization, and even more difficult to be granted leadership positions.[22][1]

Federació Ibèrica de Joventuts Libertàries (FIJL, JJLL or JJAA) was founded in 1932 as an anarchist youth organization, becoming the third most important anarchist organization of its day. Like the CNT and FAI, it largely rejected women's issues and discouraged women from becoming involved in its governance.[1] Like the FAI and CNT, it focused on the rights of Spain's working class.[1]

- Mujeres libres

Existing tensions within the anarchist movement, resulting from the exclusion or discouragement of women by the male leadership, eventually led to the creation of Mujeres Libres by Lucia Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón in May 1936, shortly before the start of the Civil War.[7][13][30][22][6][1] Suceso Portales served as the national vice-secretary.[30] Initially based in Madrid and Barcelona, the organization had the purpose of seeking emancipation for women.[7][13] One of their goals was "to fight the triple enslavement to which (women) have been subject: enslavement to ignorance, enslavement as women and enslavement as workers".[6] It was from the anarchist movement that many militia women (Spanish: milicianas) were to be drawn.[7]

Mujeres Libres organized ideological classes designed to raise female consciousness. Compared to their fellow Second Wave feminists in the United States, they were more radical in that they provided job training skills, health information sessions, and reading classes. Better information facilities for women were viewed as critical if women were to participate in the wider revolutionary movement.[22][6][1] Lack of education was one of the reasons men had sidelined many of the women in the movement, and Mujeres Libres sought to overcome the sexist approach.[22][1] Believing women's liberation would require a variety of measures, they became ideologically closer to intersectional feminism.[22] Mujeres Libres also set up ateneos libertario (storefront cultural centers), which acted at the local level and decentralized governance, making it accessible to all. They avoided direct political engagement through lobbying of the government.[22][6][1] They did not identify as feminist, as they saw goals of other feminists at the time as too limited in scope for the freedom they sought for their fellow women, perceiving feminism as too bourgeoisie.[1] It was only in the 1990s that academics began to view them as feminists.[1]

Anti-fascists

Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) was one of the major anti-fascist organizations during the Second Republic. Its goals in the early part of this period included giving working-class women a feeling of empowerment. To this end, the Women's Secretariat set about organizing neighborhood women's committees to address day-to-day concerns of women living in specific areas.[31] POUM's Women's Secretariat also gave weapons training to women in cities like Barcelona. They wanted women to feel prepared for the war that seemed inevitable.[31]

Known as the Women's Cultural Grouping in Barcelona, POUM's women's group also organized classes attracting hundreds of women participants. They focused on hygiene, knitting, sewing, reading, child welfare and covered a broad range of topics including socialism, women's rights, and the origin of religious and social identities.[31] Contacts took place in this period between POUM's Alfredo Martínez and leadership in Mujeres Libres in Madrid about the possibly of forming an alliance although they did not result in any action.[31]

Communists

During the Second Republic, Partido Comunista de España (PCE) was the primary Communist political organization in Spain.[32] Communists began to recognize the importance of women during the Second Republic, and started to actively seek female members to broaden their female basis in 1932.[10] To further this goal, the first Communist women's organization, Committee of Women against War and Fascism in Spain, was created to attract women to Communist-connected unions in 1933.[10] Membership for women in PCE's Asturias section in 1932 was 330, but it grew. By 1937, it had increased to 1,800 women.[10]

The Spanish Committee of Women against War and Fascism was founded as a women's organization affiliated with Partido Comunista de España in 1933.[10] It was a middle-class feminist movement.[8] As a result of PCE male governance trying to remove women from more active roles in the Communist movement, its name was changed to Pro-Working Class Children Committee around 1934 following the Asturian miners strike.[10] Dolores Ibárruri, Carmen Loyola, Encarnación Fuyola, Irene Falcón, Elisa Uriz and María Martinez Sierra, part of a larger group representing Spain's communist, anarchist and socialist factions, attended the 1933 World Committee of Women against War and Fascism meeting in France.[8]

During the Asturian miners action, the government of the Second Republic responded by arresting thousands of miners and closing down their workers centers. Women rose up to support striking and imprisoned miners by advocating for their release and taking jobs to support their families. PCE's male leadership strove to find roles for women that better suited their gender and were better fitted for the new, more conservative legal framework evolving under the Second Republic. PCE's goal, which was achieved, was to discourage women's active participation in labor protests.[10]

VII Comintern Congress in 1935 in Moscow had two representatives from the PCE, Ibárruri and Jose Díaz.[8] Ibárruri's profile rose so much during the Second Republic, while being coupled with the outlawing of the Communist Party, that she was regularly hunted by the Spanish police. This made it difficult for her to travel, both internally and externally.[8] Being too close to her would also prove deadly. Twenty-three year old Juanita Corzo, a member of Women Against War, was given a death sentence in 1939 for aiding Ibárruri, later commuted to life in prison.[8]

Women in Partido Comunista de España faced sexism on a regular basis, which prevented them from rising up the ranks of leadership. They were denied the ability to be fully indoctrinated by keeping them out of Communist ideological training classes. At the same time, men insisted women were not capable of leadership because they were not educated in these principals. The sexism these leftist women faced was similar to their counterparts on the right, who were locked out of activities of the Catholic Church for the very same reason.[32]

For the 1936 May Day celebrations, the Communist Party of Spain worked hard to convey a perception that they were one of the dominant political groups in the country by turning out party members in Madrid. They successfully organized hundreds of Communist and Socialist women to participate in a march, where they chanted "Children yes, husbands no!" (Spanish: Hijos sí, maridos no!) with their fists clenched in the air behind huge Lenin and Stalin banners.[12] That year, the party was also successful in convincing many socialist women to embrace Bolshevism.[12]

Republicans

Republican Union Party (Spanish: Partido de Unión Republicana) (PUR) was the largest Republican party. Despite many divisions on the left, there were Communist and other women PUR community centers, where they would interact with leftist women and discuss the political situation of the day during the early period of the Second Republic. Participants included Dolores Ibárruri, Victoria Kent and Clara Campoamor. Many of these women were very knowledgeable on these topics, more so than many of their male peers.[8] This cross-party collaborative discussion was at times threatening to male leaders such as those in the Republican Union Party, who in 1934 put a stop to it by posting police officers at the entrances to keep non-party members out. As a consequence, many women left the Republican Union Party.[8]

Socialists

Prominent women socialists included Matilde Huici, Matilde Cantos and Matilde de la Torre.[4] Women's caucuses were often very weak inside the broader socialist party governance structure. As a consequence, they were often ineffective in advocating for women's rights.[4]

In general, men inside PSOE began espousing a more militant approach to combating right wing actors inside Spain, continuing this thinking as the history of the Second Republic chugged along in the face of increasing numbers of labor conflicts and male leadership quarrels. This militancy though did not carry over into beliefs about activities for its female membership.[10][4]

Nelken was the political leader of the PSOE's women's wing. Her feminist beliefs worried and threatened her male colleagues in the Cortes. Despite this, Nelken was the only woman during the Second Republic to win three elections for the Socialists to serve in the Cortes. Her election wins came in 1931, 1933 and 1936. Disillusionment with the party led her to change membership to the Communist Party in 1937.[3] During the immediate pre-Civil War period, Campoamor tried to rejoin the Spanish socialists but was repeatedly rejected. Her support of universal suffrage, feminist goals and divorce had made her an anathema to the male dominated party leadership. Eventually, in 1938, she went into exile in Argentina.[3] María Martínez Sierra served for a time as a Socialist deputy in 1933.[8]

October Revolution of 1934

Women played roles behind the scenes in one of the first major conflicts of the Second Republic, when workers' militias seized control of the mines in Asturias.[32][10] Originally planned as a nation-wide strike, the workers collective action only really took place in Asturias.[10] Some women were involved in propaganda and others in assisting the miners. After the government quelled the insurrection by bringing in Moroccan legionaries, some 30,000 people were jailed and another 1,000 were buried. A large number of those jailed were women. Women also played an advocacy role in trying to have their husbands and male relatives released.[32]

During the protests by the Asturian miners, the government of the Second Republic responded by arresting thousands of miners and closing down their workers centers. Women rose up to support striking and imprisoned miners by advocating for their release and taking jobs to support their families. Following this, Partido Comunista de España tried intentionally to prevent its female membership becoming more politically active from within the party.[10] During fighting in Oviedo, women were on the battlefield serving in a variety of roles. At least one attended to the wounded while shelling went on around her. Others took up arms. Still more went from leftist position to leftist position under active shelling, providing fighters with food and encouragement.[10]

During the Asturian conflict, there were a few instances of women-initiated violence. This fed into paranoia among those on the right that women would violently try to seize power from men. Neither on the left or the right were these women viewed as heroic; indeed, men hoped to limit their potential for further political action.[10] Women were also involved in building barricades, repairing clothing, and undertaking street protests. For many, this was the first time they were engaged without a male chaperone as in many cases, they were working on behalf of imprisoned male relatives.[33] Some women were killed in the conflict. Aida Lafuente was active on the front, and died during the Asturian conflict.[33]

A number of women played important organizational roles behind the scenes. They included Dolores Ibárruri, Isabel de Albacete and Alicia García. They were aided by the PCE's Committee to Aid Workers' Children.[8]

More recently, academics have been discussing whether the Asturian miners's strike represented the real start of the Spanish Civil War.[10] Imagery from the conflict was subsequently used by both sides for propaganda to further their own agenda, particularly inside PSOE who saw the situation as a call for political unity on the left if they were to have any hope of countering what they viewed as the rise of fascism.[10] PSOE consequently used gendered imagery to sell their ideas.[10] Propaganda used the events of October 1934 to feature women in gender-conforming ways that did not challenge their roles as feminine. This was done by the male leadership with the intention of counteracting the image of strong female political leaders, who unnerved many on the right. Right-wing propaganda at the time featured women as vicious killers, who defied gender norms to eliminate the idea of Spanish motherhood.[10]

Start of the Civil War

On 17 July 1936, the Unión Militar Española launched a coup d'état in North Africa and Spain. They believed they would have an easy victory. They failed to predict the people's attachment to the Second Republic. With the Republic largely maintaining control over its Navy, Franco and others in the military successfully convinced Adolf Hitler to provide transport for Spanish troops from North Africa to the Iberian peninsula. These actions led to a divided Spain, and the protracted events of the Spanish Civil War.[7][27][34][22][35][10] It would not officially end until 1 April 1939.[35][10]

Franco's initial coalition included monarchists, conservative Republicans, Falange Española members, Carlist traditionalist, Roman Catholic clergy and the Spanish army.[26][7][29] They had support from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.[26][35] The Republican side included Socialists, Communists, and various other left-wing actors.[26][34][35]

The military revolt was announced on the radio across the country, and people took to the streets immediately as they tried to determine the extent of the situation, and whether it was a military or political conflict. Ibárruri coined the phrase "¡No pasarán!" a few days later, on 18 July 1936 in Madrid while broadcasting from the Ministry of the Interior's radio station, saying, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. ¡No pasarán!"[8]

At the start of the Civil War, there were two primary anarchist organizations: Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Representing working-class people, they set out to prevent the Nationalists from seizing control while also serving as reforming influences inside Spain.[22]

Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union signed the Non-Intervention Treaty in August 1936, promising not to provide material support for the war to any of the parties, even as Germany and Italy were already providing support to the rebel faction.[1][8]

Spanish Civil War (1936 - 1939)

In the Civil War period, mainstream leftist feminism often took on an individualistic approach to addressing inequalities.[30] There were often battles over the issue, whether the personal should be political and vice versa.[30]

A few groups challenged the mainstream Western feminism of the period, including Mujeres Libres.[30] While deliberately rejecting the label of feminism, the group's version of feminism was about creating leadership structures that incorporated everyone, instead of having a feminist leadership model that paralleled patriarchal ones.[30] Many feminists disliked the organization, as it was an affiliated with the CNT, where women were often locked out of leadership positions and instead encouraged to join the women's auxiliary organization.[30] Others disliked Mujeres Libres' decision to downplay the role of specific female leaders, and instead make all feminist actions appear to be the result of collectivist action.[30]

Women's rights

During the Second Republic and during the initial stages of the Civil War, there was a social and economic revolution in women's rights, especially in areas like Catalonia. Because of the nature of war, many reforms were sporadically and inconsistently implemented, and advances made during the latter half of 1936 were largely erased by May 1937.[7] On 25 December 1936, the Generalitat de Cataluña made abortion legal for the first time in the history of Spain following a decree from the Health Department. The anarchist-dominated Health Department then followed this up in March 1937 with regulations for hospitals and clinics about how to conduct abortions. The same government also for the first time provided government-sponsored information and access to birth control, coupling it with information and treatment for venereal disease.[7][36]

Women's liberation failed on the Republican side by the close of the Civil War. The lack of implementing full liberation during the peaceful period of the Second Republic was a leading cause, as sexist thinking that existed on that side had continued to exist and was reinforced as the war progressed.[7]

Gender roles

The Spanish Civil War served to break traditional gender roles on the Republican side. It allowed women to fight openly on the battlefield, a rare occurrence in twentieth century European warfare.[7][4] The war also served to remove the influence of the Catholic Church in defining gender roles on the Republican side.[7]

While the war broke down gender norms, it did not create progress on equitable employment or remove domestic tasks as the primary role of women. Behind the scenes, away from the front, women serving in personal family and Republican opposition support roles were still expected to cook for soldiers, launder their uniforms, look after children and tend to dwellings.[36] Women supporting CNT militants were relieved of these gender roles but were still expected to serve male fighters in the traditional way.[36]

Political parties and political activity

During the Spanish Civil War, various political and government forces on the Republican side tried to encourage women's participation.[7] Only one group acted overtly on feminist goals, namely Mujeres Libres.[6] For the remaining political parties, labor groups and government organizations, women's rights and feminist goals were not among their top concerns.[6]

Working-class girls involved with both anarchists and socialists often chastized women from other villages who came from different left-wing political parties. There was a lack of solidarity. Pilar Vivancos explained this as a result of a lack of education among women, with patriarchy within parties being used to set women against each other instead of collectively working towards emancipation of women. They did not understand what it truly meant, and it made them vulnerable to political puritanism that would later sweep through the left.[36]

Anti-Fascists

Anti-fascist organizations often attracted a heterogeneous membership. This at times could lead to major differences, discrepancies and priorities when it came to implementing anti-fascist programs.[4] Different groups including socialists, communists and anarchists would sometimes try to take advantage of this inside these organizations.[4]

POUM was the dissident communist party during this period. It tried to encourage women to join specifically female sub-organizations.[4] While the Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas (AMA) represented women from a wide variety of anti-fascist political backgrounds, it ended up serving as a vehicle of communist orthodoxy designed to mobilize women to support the Communist cause on the Republican side of the civil war.[4]

Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista had women both in high level leadership positions and in leadership spots further down the hierarchy. In contrast, Mujeres Libres was a CNT auxiliary, and the women were often denied a specific spot at the table as there was a view among anarchist leaders that adults, not women, should be the ones to make decisions.[31] Anarchists often were unwilling to give support to women combating gender-based problems at this time.[31] There were always questions of whether women should be fully integrated or should work in women-only groups to achieve specific aims. This resulted in making the movement less effective in accomplishing goals related to women.[31]

- Mujeres Libres

Mujeres Libres became one of the most important women's anarchist organizations during the Civil War.[7][37] Their Civil War ranks were aided by women moving over from the CNT to participate in the organization.[30] The organization's importance was a result of their different These included running educational programs, and trying to increase women's literacy. They also organized collective kitchens, parent-controlled daycare centers, and provided prenatal and infant health information to expecting parents.[7][37] One of their more significant struggles during the Civil War was centered on fighting prostitution.[7][37] Education was viewed a key aspect here, as it was believed educated women would be less likely to turn to prostitution. There were over 20,000 members by 1938.[7][30][22] Mujeres Libres also published a journal of the same name. Articles focused on personal autonomy, the creation of female identities, and self-esteem.[13][9] It also often addressed the conflicts in identity between being a woman and being a mother, and how women should navigate their identities as maternal figures.[9]

The October 1938 CNT congress in Barcelona did not welcome Mujeres Libres, barring entry to a delegation of 15 women. Women had previously been allowed to attend, but only as representatives of other, mixed gendered anarchist organizations. A women's only organization was not tolerated. The women protested but did not get an explanation until an extraordinary meeting of the CNT on 11 February 1939. When the response came, it was that "an independent women's organization would undermine the overall strength of the libertarian movement and inject an element of disunity that would have negative consequences for the development of working-class interests and the libertarian movement on the whole."[1]

Foreign anarchists found organizations like Mujeres Libres baffling, as discussions around women's rights by Spanish anarchist women were often based around expanding rights while at the same time maintaining traditional gender roles.[37] Older members were often critical of younger ones, viewing them as being too hesitant to act and considering them obsessed with sexuality, birth control and access to abortions.[30]

Mujeres Libres folded before the end of the Civil War.[22]

Communists

While other communist organizations existed, Partido Comunista de España (PCE) remained the dominant one.[32][34] In the first year of the Civil War, the PCE rapidly increased membership almost three-fold. Among the peasantry, women represented nearly a third of its members.[12]

During the Civil War, Ibárruri earned herself the nickname of La Pasionaria as she traveled around the country to speak in opposition to the Francoist forces. She used radio to disseminate her message, gaining fame by calling men and women to arms with her "¡No pasarán!" Another of her famous sayings during the Civil War was: "It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees." The Communist Party did not approve of her private life, telling her to end her relationship with a male party member who was 17 years her younger. She complied.[11]

Socialists

During the Civil War, socialist groups still tended to lack female participation as a result of the same broader pre-war problems that continued to exist. When socialist women wanted to get involved, they either had to do so through socialist youth organizations or they had to switch allegiances to the communists, who accepted women more readily and were more likely to put them into leadership positions.[13]

Abroad, socialist women were more active in their opposition to the Spanish Civil War. Belgian women socialists were opposed to their socialist party's neutrality during the Civil War. To counter this, these women socialists were active in trying to evacuate refugees. They managed to send 450 Basque children to Belgium in March 1937. With the assistance of the Belgian Red Cross and Communist's Red Aid, socialist women organized the placement of 4,000 Spanish refugees.[38]

PSOE continued to ignore the unique problems of women during the Civil War. When women were interested in joining the party, they found they could not be promoted to leadership positions. PSOE also refused to send women to the front, perpetuating the sexist belief that a woman could best serve the war effort by staying at home.[13] One of the few publicly socialist identified militia women in this period was María Elisa García, who served as a miliciana with the Popular Militias as a member Asturias Battalion Somoza company.[13]

Women's media and writing

The Spanish Civil War inspired many works of fiction and non-fiction, written by Spanish and international writers. As a result, it would later be labeled the "Poet's War". While there would be many literary compilations and literary analyses of these works during and following the war, few if any touched on the work produced by women writers in this period.[13]

As the Civil War progressed, more anti-fascist organizations began publishing magazines and newspapers for women, specifically addressing their needs. This had a flow-on effect of increasing women's personal agency.[7] Mujeres Libres published a journal of the same name. Its articles focused on personal autonomy, the creation of female identities, and self-esteem.[13]

The militia women or milicianas on the front often wrote about their experiences for publication in party-supported media. One of their favorite topics was inequality on the front, and the hope that in addition to combat, they would also take on support roles like tending to the injured, cooking and cleaning while male colleagues were afforded time to rest.[39]

Francoist Spain (1938 - 1973)

Mainstream feminism largely disappeared from public discourse, replaced by an oppressive form of state-sponsored feminism that was no more than support for Spain's traditional gender roles denying women personal and political autonomy.[13][9] Sección Femenina de Falange tried to depict feminism as a form of depravity, associating it with drug abuse and other evils plaguing society.[13] State-supported feminism, expressed through Sección Femenina, presented Isabel the Catholic and Teresa of Avila as symbols of inspiration for Spanish women. They had first been used by Francoist women during the Civil War, and reminded women that their role was to become mothers and to engage in pious domesticity.[9]

Gender roles

The end of the Civil War, and the victory of fascist forces, saw the return of traditional gender roles in Spain. They included the unacceptability of women serving in combat roles in the military.[7] Where gender roles were more flexible, it was often around employment issues where women felt an economic necessity to make their voices heard.[7] It was also more acceptable for women to work outside the home, though the options were still limited to roles defined as more traditionally female, such as working as nurses, or in soup kitchens or orphanages.[7] Overall though, the end of the Civil War proved a double loss for Republican women, as it first took away their limited political power and the identities as women that they had won during the Second Republic and secondly, it forced them back into the confines of their homes.[35]

With strict gender norms back in place, women who had found acceptable employment before and during the Civil War found employment opportunities even more difficult in the post-war period. Teachers who had worked for Republican schools were often unable to find employment.[13] Gender norms were further reinforced by Sección Femenina de Falange. Opportunities to work, study or travel required taking classes on cooking, sewing, childcare and the role of women before they were granted. If women did not attend these classes, they were denied these opportunities.[13]

Women's rights

The pillars for a New Spain in the Franco era became national syndicalism and national Catholicism.[4] Following the Civil War, the legal status for women in many cases reverted to the terms of the Napoleonic Code that had first been incorporated into Spanish law in 1889.[13] The post Civil War period saw the return of laws that effectively made wards of women. They were dependent on husbands, fathers and brothers if they wished to work outside the home.[13][40] It was not until later labor shortages that laws around employment opportunities for women changed. The laws adopted in 1958 and 1961 provided a very narrow opportunity for women to be engaged in non-domestic labor outside the household.[13] In March 1938, Franco suppressed the laws regarding civil matrimony and divorce that had been enacted by the Second Republic.[4] The 1954 Ley de Vagos y Maleante saw further repression directed towards women, specifically those who were lesbians. The law saw many lesbians committed, put into psychiatric institutions and given electroshock treatment.[41]

The Franco period saw an extreme regression in the rights of women. The situation for women was more regressive than that of women in Nazi Germany under Hitler. Women needed permission for involvement in a variety of basic activities, including applying for a job, opening a bank account or going on a trip. Legislation during the Franco period allowed husbands to kill their wives if they caught them in the act of adultery.[37]

Political organizations and activists

Mainstream feminism in Spain went underground and became clandestine in the post-Civil War period in response to the crackdown instituted by Francoist Spain. Partido Comunista de España became the dominant clandestine political organization in Spain following the end of the Civil War and continued to be involved in feminist activities. It retained this position until it was replaced by the PSOE after Franco's death. Women were involved with the party, helping to organize covert armed resistance by serving in leadership roles and assisting in linking up political leaders in exile with those active on the ground in Spain.[32]

Women's media and writing

Margarita Nelken, María Martínez Sierra and Carmen de Burgos had all been pre-Civil War feminist writers. Following the war, their work was subjected to strict censorship. Spanish feminists in Spain in the post Civil War period often needed to seek exile in order to remain active. Works produced by these writers included Nada by Carmen Laforet in 1945 and La mujer nueva in 1955, Primera memoria by Ana María Matute in 1960. Writings of some foreign feminists also found their way to Spain, including the Le deuxième sex published in French in 1947 by Simone de Beauvoir.[13]

Inside Spain, well connected, often aristocratic Spanish feminists were sometimes able to publish their works for domestic consumption by 1948. These included works by María Lafitte, Countess of Campo Alanaga, and Lilí Álvarez. Works by Republican pre-war feminists like Rosa Chacel and María Zambrano, who continued to write from exile, also saw their works smuggled into Spain.[13]

Addendum

The valuable contributions by Spanish women and feminists fighting on the Republican side have been under reported, and women's own stories have frequently been ignored. One of the major reasons for this was the sexism that existed at the time. Women and the problems of women were just not considered important, especially by the Francoist victors. When women's involvement in the Civil War was discussed, it was treated as a bunch of stories not relative to the overarching narratives of the war or a broader feminist movement. At the same time, because Nationalist forces won the war, they wrote the history that followed. As they represented a return to traditional gender norms, they had less reason than Republican forces to discuss the importance of feminists and women's involvement on the losing side of the war.[7][35]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y de Ayguavives, Mònica (2014). Mujeres Libres: Reclaiming their predecessors, their feminisms and the voice of women in the Spanish Civil War history (Masters Thesis). Budapest, Hungary: Central European University, Department of Gender Studies.

- ^ a b "La primera associació feminista". Curiositat.cat (in Catalan). 13 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Mangini, Shirley; González, Shirley Mangini (1995). Memories of Resistance: Women's Voices from the Spanish Civil War. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300058161.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Nash, Mary (1995). Defying male civilization: women in the Spanish Civil War. Arden Press. ISBN 9780912869155.

- ^ Morcillo, Aurora G. (2010). The Seduction of Modern Spain: The Female Body and the Francoist Body Politic. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 9780838757536.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ryan, Lorraine (January 2006). "A Case Apart: The Evolution of Spanish Feminism". In Pelan, Rebecca (ed.). Feminisms within and without. Galway: National Women Studies Centre. pp. 56–68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Lines, Lisa Margaret (2012). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ibárruri, Dolores (1966). Autobiography of La Pasionaria. International Publishers Co. ISBN 9780717804689.

- ^ a b c d e Memory and Cultural History of the Spanish Civil War: Realms of Oblivion. BRILL. 2013-10-04. ISBN 9789004259966.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Bunk, Brian D. (2007-03-28). Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822339434.

- ^ a b Cook, Bernard A. (2006). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097708.

- ^ a b c d Payne, Stanley G. (2008-10-01). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300130782.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bieder, Maryellen; Johnson, Roberta (2016-12-01). Spanish Women Writers and Spain's Civil War. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134777167.

- ^ a b c Glenn, Kathleen Mary; Rodríguez, Mercedes Mazquiarán de (1998). Spanish Women Writers and the Essay: Gender, Politics, and the Self. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826211774.

- ^ a b "10 de las mujeres más influyentes en la lucha feminista en España". El Rincon Legal (in Spanish). 8 March 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Louis, Anja (2005). Women and the Law: Carmen de Burgos, an Early Feminist. Tamesis Books. ISBN 9781855661219.

- ^ a b c d e Ripa, Yannick (2002). "Féminin/masculin : les enjeux du genre dans l'Espagne de la Seconde République au franquisme". Le Mouvement Social (in French). 1 (198). La Découverte: 111–127. doi:10.3917/lms.198.0111.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b Giménez Martínez, Miguel Ángel (Summer 2018). "La representación política en España durante la dictadura de Primo de Rivera". Estudos Históricos. 31 (64) (64 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: 131–150. doi:10.1590/S2178-14942018000200002.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b González Naranjo, Rocío (1 March 2017). "Usar y tirar: las mujeres republicanas en la propaganda de guerra". Los ojos de Hipatia (in European Spanish). Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Hastings, Alex (18 March 2016). "Mujeres Libres: Lessons on Anarchism and Feminism from Spain's Free Women". Scholars Week. 1. Western Washington University.

- ^ a b Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Texto íntegro del discurso de Clara Campoamor en las Cortes". El País (in Spanish). 1 October 2015. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d "CLARA CAMPOAMOR: Una mujer, un voto". Universidad de Valencia (in Spanish). Donna. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Linhard, Tabea Alexa (2005). Fearless Women in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826264985.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Angela (2003-09-02). British Women and the Spanish Civil War. Routledge. ISBN 9781134471065.

- ^ a b c d e Montero Barrado, Jesús Mª (October 2009). "Mujeres Libres". El Catoblepaz (92 ed.). Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. AK Press. ISBN 9781902593968.

- ^ a b c d e f g Evans, Danny (2018-05-08). Revolution and the State: Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Routledge. ISBN 9781351664738.

- ^ a b c d e f Cuevas, Tomasa (1998). Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791438572.

- ^ a b Seidman, Michael (2002-11-23). Republic of Egos: A Social History of the Spanish Civil War. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299178635.

- ^ a b c Petrou, Michael (2008-03-01). Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774858281.

- ^ a b c d e f Martin Moruno, Dolorès (2010). "Becoming visible and real: Images of Republican Women during the Spanish Civil War". Visual Culture & Gender. 5: 5–15.

- ^ a b c d Fraser, Ronald (2012-06-30). Blood Of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War. Random House. ISBN 9781448138180.

- ^ a b c d e Hochschild, Adam (2016-03-29). Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547974538.

- ^ Gruber, Helmut; Graves†, Pamela; ontributors (1998-01-01). Women and Socialism - Socialism and Women: Europe Between the World Wars. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781785330063.

- ^ Lines, Lisa Margaret (May 2009). "Female Combatants in the Spanish Civil War: Milicianas on the Front Lines and in the Rearguard". Journal of International Women's Studies. 11 (4).

- ^ Schmoll, Brett (2014). "Solidarity and silence: motherhood in the Spanish Civil War" (PDF). Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. 15 (4): 475–489. doi:10.1080/14636204.2014.991491. S2CID 143025176.

- ^ Reagan, Georgia Elena (2013). "Postmemory, feminism, and women's writing in contemporary Spanish novels set in the Spanish Civil War and Franco dictatorship". Graduate School. Masters Thesis. 1. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.