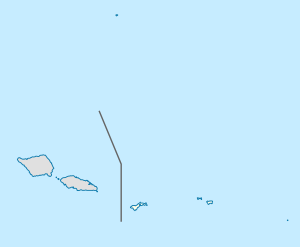

Fagaʻitua, American Samoa

Fagaʻitua | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Coordinates: 14°16′03″S 170°36′50″W / 14.26750°S 170.61389°W | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| County | Sua |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.53 sq mi (1.37 km2) |

| Elevation | 26 ft (8 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 287 |

| • Density | 540/sq mi (210/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Samoa Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799 |

| Area code | +1 684 |

Fagaʻitua is a village in the east of Tutuila Island, American Samoa. It is located on the central coast of Fagaʻitua Bay. It is in Sua County,[1] a county also known as ʻo le falelima i sasaʻe ("the house of the five in the east"). Fagaitua is located at a shallow bay on the south coast of the island, in-between Lauli'i and Alofau. It is home to Luafagā, Le'iato's house of chiefs, and the big malae Malotumau.[2]

Coral reefs at Fagaʻitua suffered significant damage during the 2009 tsunami.[3]

Fagaʻitua is home to the smallest and most rural high school in American Samoa. Fagaʻitua High School (FHS), whose student body is around 500 as of 2018, practices football at the old rugby field by Pago Pago Bay. It has never had its own field but has utilized the uneven turf at Onesosopo Park, which is replete with volcanic stubble, water, toads, and sand traps. Rob Shaffer was hired as a teacher by Fagaʻitua in February 1972 and eventually also took over coaching of the high school's football team. Shaffer has played varsity as a quarterback for Oceanside High School under head coach Herb Meyer.[4]

In 2018, a monument was made for the Fagaʻitua High School Alumni Association in order to commemorate Fagaʻitua High School's 50th anniversary. The statue will eventually be mounted onto the pedestal which was designed and constructed by the American Samoa Department of Public Works. It is located in front of Fagaʻitua High School. The statue depicts a Viking warrior with his head tilted towards the east and the Eastern Star. The statue was made locally on Tutuila Island.[5]

Etymology

The name of the village, Fagaʻitua, is derived from the Samoan language and translates into English as “Bay behind".[6]

History

In 1892, eastern Tutuila Island was the site of significant conflict among the followers of High Chief Lei’ato. According to local tradition, the Lei’ato title originated in ʻAoa on the island's north coast, near its eastern end. Lei’ato’s son later established a secondary lineage in Fagaʻitua. Over time, the Fagaʻitua branch gained prominence, with their matai becoming the leading high chief for all of eastern Tutuila. The unrest began when the inhabitants of Aoa attempted to appoint a rival high chief. In retaliation, the Lei’ato of Fagaʻitua mobilized warriors and launched a dawn raid on ʻAoa, resulting in the deaths and injuries of several villagers. The British consulate became involved after the looting of a store owned by A. Young, an English trader, and the killing of his pigs. Following these events, relatives and supporters of Lei’ato from western Tutuila traveled east to participate in the ongoing conflict.[7]

Geology

The geological formation of Fagaʻitua is centered around the Ālōfau volcanic complex, which features a shield-shaped dome composed of thinly layered basaltic lava flows, including both ʻaʻā and pāhoehoe types. These layers, along with dikes, breccias, and tuffs, create a distinctive structure that spans approximately 2.4 square kilometers on the eastern edge of Fagaʻitua Bay. The volcanic dome is situated over a rift zone that follows a northeast-southwest orientation. The lava deposits, predominantly primitive olivine basalts, are thinly bedded and exhibit a dip of 10 to 20 degrees, radiating away from the village of Ālōfau. A significant dike complex is visible along the road leading southeast from Fagaʻitua village, providing insight into the subsurface dynamics of the volcano. The region also hosts an extensive array of volcanic dikes, with around 130 individual formations exposed on a promontory to the north of Ālōfau. These features are complemented by additional dikes located south of the village, emphasizing the area's complex magmatic activity. The caldera rim, a prominent feature of this volcanic system, descends steeply toward the southwest and extends partially beneath the adjacent offshore waters.[8]

Demographics

| Year | Population[9] |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 287 |

| 2010 | 433 |

| 2000 | 483 |

| 1990 | 455 |

| 1980 | 422 |

| 1970 | 302 |

| 1960 | 309 |

| 1950 | 255 |

| 1940 | 212 |

| 1930 | 152 |

Notable residents

- Susana Leiato Lutali – former First Lady of American Samoa (1985–1989, 1993–1997)[10]

- Blessman Ta'ala – football player

- Muagututiʻa Moevasa Tauoa – politician

References

- ^ Tuʻuʻu, Misilugi Tulifau Tofaeono (2002). History of Samoa Islands: Supremacy & Legacy of the Malietoa (na Fa'alogo i Ai Samoa). Tuga'ula Publication. Page 427. ISBN 9780958219914.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 426. ISBN 9780824822194.

- ^ "American Samoan coral damage reassessed". 3 November 2009.

- ^ Ruck, Rob (2018). Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL. The New Press. ISBN 9781620973387.

- ^ "Commemorative monument sparks criticism from some FHS alums". 13 July 2018.

- ^ Churchill, W. (1913). "Geographical Nomenclature of American Samoa". Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, 45(3), page 191. Retrieved on December 6, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.2307/199273.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Pages 95-96. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Keating, Barbara H. and Barrie R. Bolton (2012). Geology and Offshore Mineral Resources of the Central Pacific Basin. Springer New York. Page 152. ISBN 9781461228967.

- ^ "American Samoa Statistical Yearbook 2016" (PDF). American Samoa Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ "Funeral services for Mrs. Susana Lutali set for June 29". Samoa News. 2012-06-24. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved 2022-01-30.