Eastern Command of the Pakistan Army

| Eastern Command | |

|---|---|

Insignia of GHQ Pakistan | |

| Active | 23 August 1969–16 December 1971 |

| Country | |

| Eastern Command Headquarters | Dacca Cantonment, East Pakistan, Pakistan (now Dhaka, Bangladesh) |

| Commanders | |

| Corps Commander | Lt. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi |

| Chief of Staff | Brig. Baqir Siddiqui |

| Notable commanders | Lt. Gen. Sahabzada Yaqub Khan VADM. Syed Mohammad Ahsan |

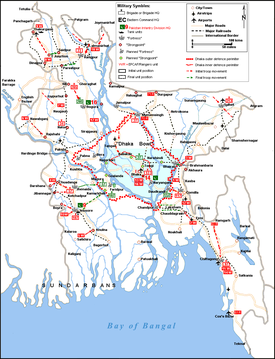

The Eastern Command of the Pakistan Army (initially designated as III Corps) was a corps-sized military formation headed by a lieutenant-general, who was designated the Commander Eastern Command. After the partition of India by United Kingdom, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was divided into two territories separated by 1,000 miles (1,600 km) (prior to the independence of Bangladesh in 1971). Most of the assets of the Pakistan armed forces were stationed in West Pakistan; the role of the Pakistan armed forces in East Pakistan was to hold that part of the country until the Pakistani forces defeated India in the west (in case of war).[1] The Pakistan Army created the Eastern Command, with one commander in the rank of Lieutenant General responsible for the command. The armed forces (particularly the Pakistan Army), had drawn up a plan to defend Dhaka by concentrating all their forces along the Dhaka Bowl (the area surrounded by the rivers Jamuna, Padma and Meghna).[2]

After Pakistan launched Operation Searchlight and Operation Barisal to curb the Awami League-led political movement in March 1971 (leading to the creation of Mukti Bahini and insurgency throughout Bangladesh), Lieutenant General A. A. K. Niazi revised the existing plan according to the Pakistan Army's General Headquarters (GHQ) directive (which emphasized the need to prevent the Mukti Bahini from occupying any area of the province and to fight for every inch of territory).[3][4] HQ expected the Indians to occupy a large area of the province, transfer the Mukti Bahini and Bengali refugees there and recognize the Bangladesh government in exile – turning the insurgency into an international diplomatic issue.[5] Lieutenant General Niazi designated 10 cities (Jessore, Jhenaidah, Bogra, Rangpur, Jamalpur, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla and Chittagong) on major communication hubs as "fortress towns" and placed the bulk of his troops near the Indian border.[6][7] The final plan called for the armed forces to delay Indian attacks at the border and then gradually fall back to the fortress towns.[8] From the fortresses, part of the surviving force was to take up positions near Dhaka and hold out until India was defeated in the west; Pakistani forces in the fortress towns would delay the bulk of the Indian forces and prevent them from concentrating on Dhaka.

Background

The Pakistan Army inherited six infantry divisions and an armored brigade after independence in 1947 from the British Indian Army,[9] deploying most of their armed assets in West Pakistan. East Pakistan had one infantry brigade in 1948, which was made up of two infantry battalions, the 1st East Bengal Regiment and the 1/14th (1st battalion of 14th Punjab Regiment) or 3/8th Punjab Regiment (3rd battalion of the 8th Punjab Regiment). Between them, the two battalions boasted five rifle companies (a battalion normally had five companies).[10] This weak brigade – under the command of Brigadier Ayub Khan (served as an acting Major General – appointment: GOC, 14th Infantry Division) – and a number of East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) wings were tasked with defending East Pakistan during the Kashmir War of 1947.[11] The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) and Pakistan Navy had little presence in East Pakistan at that time. The reasons for placing more than 90 percent of the armed might in West Pakistan were:

- West Pakistan borders Kashmir (an issue the Pakistani government was not above using armed force to resolve): Pakistan did not have the economic base to support adequate forces in both wings, and West Pakistan had more strategic relevance than East Pakistan.[12]

- Most government officials were from West Pakistan or non-Bengali. Most economic development was taking place in West Pakistan, and the bulk of the armed forces was placed there to keep its power base secure. Pakistani military staff planners proposed the following doctrine to justify this deployment: "The defense of the East lies in the West".[13] Broadly speaking, this translated into Pakistan defeating India in the west, regardless of what transpired in the east (including Indian occupation of East Pakistan)[14] because the presumed West Pakistani success would force India to negotiate a favorable settlement.[15] The Pakistani staff also believed in the martial race theory; it was widely believed that one Pakistani soldier was equal to four to ten Hindus/Indian soldiers,[16][17] and that the numerical superiority of the Indian armed forces could be negated by a smaller number of Pakistani soldiers.[18]

1949–1965

The Pakistan Armed Forces grew significantly in size between the wars of 1949 and 1965. The number of infantry divisions jumped from 6 to 13; it also boasted two armored divisions and several independent infantry and armored brigades by 1965.[19] All these formations had the required artillery, commando, engineer and transport units attached to them. The growth in military infrastructure was slower in East Pakistan; the single division (14th Infantry division) HQed at Dhaka now contained two infantry brigades, with the 53rd Brigade stationed at Comilla and the 107th Brigade deployed in Jessore by 1963.[20] In 1964, the 23rd Brigade was created in Dhaka. This under-strength division comprised three infantry brigades, with no armour and supported by 10 EPR wings, 12 F-86 Saber planes, and three gunboats[21] rode out the 1965 war in the east. The Air Forces had bombed each other's bases with the PAF emerging on top, while the Border Security Force (BSF) and EPR had skirmished along the border; although India had one infantry division and one armoured brigade posted near East Pakistan, the armies never clashed in the east.[citation needed]

Reforms of Yahya Khan

When Yahya Khan became Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army in 1966, he initiated a series of reforms to revamp the combat capability of the Pakistan army. In East Pakistan a corps headquarters was to be established (initially designated as the III corps which later known as the Eastern Command),[22] but except the 14th Infantry Division, Dacca no new division was raised (although the 57th Infantry Brigade was formed in Dhaka, while the 23rd Infantry Brigade was sent to Rangpur).[23] In 1970, the 29th Cavalry was deployed in Rangpur from Rawalpindi, but East Pakistan was not given any corps artillery or armoured units.

The Pakistan Eastern Command headquarters was inaugurated in Dacca Cantonment, Dacca on 23 August 1969 and Lt. Gen. Sahabzada Yaqub Khan was appointed as the commander; on 1 September 1969, the Chief Martial Law Administrator of the country, General Yahya Khan, sent Vice-Admiral Syed Mohammad Ahsan as Martial Law Administrator of East Pakistan.[24] Syed Mohammad Ahsan, when Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Navy, had established the naval forces in East Pakistan; the naval presence was tripled in East Pakistan with more officers from West Pakistan deployed in the region. Earlier, The Chief of the General Staff at GHQ, Rawalpindi, Major General Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, decided to run a series of exercises in East Pakistan to formulate an integrated battle plan for the province in 1967. Dubbed "Operation X-Sunderbans-1", it was run by (then) Colonel Rao Farman Ali under the command of Major General Muzaffaruddin (GOC 14th Division); the conclusions of this exercise formed the basis for the Pakistani operational plan in 1971.

Operation X-Sundarbans-1

Pakistani planners assumed that the main Indian assault would take place on the western border of East Pakistan, and the army in East Pakistan would not defend every inch of the province. Pakistani staff planners identified the following features as significant for setting up a defence plan:[25]

- Monsoon rains turn the mostly flat country into a morass which hinders movement; the best time for conventional warfare is between November and March, when the ground firms up to allow easy mechanized movement and armoured warfare.

- Infrastructure is poor; navigable rivers cut across roads, and many places can only be reached by dirt roads. There are 300 large canals (navigable during summer), which can be an obstacle or helpful for the battle plan. Control over air and rivers are necessary for unhindered movement along interior lines, and road conditions dictate the speed and direction of movement.

- East Pakistan was a salient into Indian territory, and could be used to launch attacks only if the forces posted there were stronger than the Indian forces opposing them. There were some Indian salients into the province also.

Instead of defending every inch of the land, survival of the armed forces was given top priority and the defence of Dhaka was the ultimate objective.[26] Instead of deploying along the 2,600-mile (4,200 km)-long Indian border, three lines of deployment were chosen:[27]

- The Forward Line: Roughly forming a semicircle running from Khulna – Jessore – Jhenaidah – Rajshahi – Hili – Dinajpur – Rangpur – Jamalpur. Mymensingh – Sylhet - Comilla – Chittagong. The Pakistan army did not have the numbers to defend this line.

- The Secondary Line: This began along the Madhumati River, ran north to the Padma River, ran west along the Padma to Rajshahi, then north to Hili, then to Bogra, Jamalpur, Mymensingh to Bhairab, then south to Comilla and back to Faridpur along the Meghna River. Khulna, Jessore, Jhenida and Dinajpur-Rangpur were not to be defended in force; Sylhet and Chittagong were to be independent defence areas.

- Inner Line: The Dhaka Bowl (the area between the Jamuna, Padma, Meghna and Old Brahmaputra Rivers). This (especially the city of Dhaka) must be defended until Pakistan defeated India in the west.

The Pakistani planners were aware of the possible negative political implications among the Bengali population of abandoning forward areas and concentrating the army around the Dhaka Bowl to maximise the defensive potential and achieve better co-ordination; however, it failed to come up with an alternative solution. The planners recommended taking advantage of the poor state of infrastructure and natural obstacles to the fullest.

In brief, the plan was:

- Pakistani troops in Rangpur will move south, defend the area around Hili – Bogra and fall back to the Dhaka Bowl while troops from Rajshahi (after defending the Hardinge Bridge) retreated to the Dhaka Bowl.

- Troops in Jessore will fall back to the Madhumati river and defend the area between Magura and Faridpur.

- Troops in Dhaka (if needed) would move north to defend the Jamalpur-Mymensingh-Bhairab area. The area north of Dhaka was deemed hazardous for military activity, and the Pakistan planners thought the hill country north of the border would impede Indian army activity.[28]

- Troops from Comilla would move west and defend the area between Chandpur, Bhairab and Daudkandi.

Pakistani forces stationed in Sylhet (which, surrounded by Indian territory from three sides, would be extremely difficult to defend) and Chittagong would look after their own affairs. The planners did not devise a plan whereby East Pakistan forces would fight a self-sustained, independent action and defend the province on its own.[29]

Operation Titu Mir

A series of exercises, codenamed "Titu Mir", was conducted by the Eastern Command in 1970; the last was staged in January. The conclusions drawn were:[30]

- India would launch the main assault on East Pakistan from the west, aiming to capture the area up to the river Jamuna; secondary efforts, directed towards Sylhet and Chittagong, would take place in the east.

- Only with the fall of Dhaka would the capitulation of the province be completed.

- Against a conventional Indian attack with 3:1 superiority in numbers and enemy dominance of the air and sea, an East Pakistan armed force contingent consisting of a single infantry division (supported by a regiment of tanks, 17 EPR wings and other paramilitary forces, a squadron of jets and four gunboats) with no support from West Pakistan would probably be able to last for a maximum of three weeks.[31]

The conclusions were submitted to GHQ in Rawalpindi, but no major alteration of the original plan took place at this time.

Operations Searchlight and Barisal

During 1971, Pakistan experienced riots and civil disobedience against the military dictatorship in both east and west. The Martial law administrator of East Pakistan, Vice-Admiral S.M. Ahsan was East Pakistan's governor also. The positions of the Pakistan armed forces under Admiral Ahsan were changed and deployed at the borders to observe Indian intelligence efforts. The magnitude of force was also increased, and logistics efforts were improved under Admiral Ahsan's command. His two-year rule saw stability and improvement in government control of the province; however, the deployment ratio of military forces increased. In March 1971, General Yahya Khan visited Dhaka to break the Mujib-Bhutto impasse. Lieutenant General Tikka Khan's staff at the Eastern Command headquarters was the first to present their assessment of the civil and military situation to General Yahya Khan and the army and air force's senior officers accompanying him, and Vice-Admiral Ahsan persuaded General Yahya Khan at the meeting. During this meeting, Admiral Ahsan brief ran counter to the cut-and-dried solutions of West Pakistan representatives and civil servants. The Pakistan Air Force's Air Commodore Mitty Masud (AOC, PAF Base Dacca) stressed the importance of a political solution rather than military action. Air Commodore Masud backed Admiral Ahsan, as he believed that an autonomous East Pakistan was preferable to the certainty of military defeat if India decided to intervene. General Yahya Khan rejected Masud's arguments.

Before the start of military operations a final high-level meeting was held (chaired by General Yahya Khan) at the General Headquarters (GHQ), where the participants were unanimously in favour of the military operation (despite the calls from Admiral Ahsan and Air Commodore Masud for a political settlement). One of the bases of the replacement was Admiral Ahsan's resignation; he opposed any military actions in the East Pakistan, and was determined to find political solutions rather than military. The GHQ generals in the army and air force (and the navy admirals) were determined to curb the political movement with violence and military might. Admiral Ahsan went to East Pakistan, later returning to West Pakistan. General Yaqub Khan temporarily assumed control of the province in place of Admiral Ahsan; he was replaced by Lt. General Tikka Khan on his refusal to support military action against civilians. Once Operation Searchlight and Operation Barisal launched, Admiral Ahsan resigned from his position as Martial Law Administrator and Governor of East Pakistan, retiring from the Navy in protest.[32] In his place, Rear Admiral Mohammad Shariff assumed the Naval Commander of East Pakistan (Flag Officer Commanding of the Eastern Naval Command). Air Commodore Mitty Masud was also replaced by the inexperienced officer Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan. Masud resigned from the air force due to his apparent opposition to Operations Searchlight and Barisal. Lt. General Tikka Khan (Governor, Chief Martial Law Administrator and Commander of Eastern Command, ordered the formulation and implementation of Operation Searchlight after receiving approval from GHQ, Rawalpindi.

Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff, commander of the Pakistan Navy in the region, ran violent naval operations that contributed to the insurgency. The Pakistan armed forces had no reserves to meet any unforeseen events,[33] and success depended heavily on reinforcements from West Pakistan. There was no contingency plan for any Indian military action – the main reason Generals Yakub, Khadim and Farman had opposed launching the operation.[34] Pakistani forces occupied Bangladesh, and Gen. Gul Hassan, then Chief of General Staff of the Pakistan army, and no admirer of Gen. Niazi from 11 April 1971[35] – expressed satisfaction with the situation in mid-April.[36]

1971 High Command plan

The size and disposition of Pakistan combat forces in East Pakistan changed during Operation Searchlight. The 14th Division was reinforced by the 9th (made up of the 27th, 313th and 117th Brigades) and the 16th (comprising the 34th and 205th Brigades) Divisions (minus their heavy equipment and most of their supporting units)—in all, fifteen infantry and one commando battalion and two heavy mortar batteries by May 1971.[37] Until the end of 1971, General Yahya Khan's government was unable to find an active military administrator comparable to Admiral Ahsan as the civil war in East Pakistan intensified. Senior general officers and admirals were unwilling to assume the command of East Pakistan until Lieutenant-General Amir Niazi volunteered for this assignment. Lieutenant General Niazi was made the commander of the Pakistan Eastern Command (replacing Lieutenant General Tikka Khan, who remained as Chief Martial Law Administrator and Governor until September 1971). Rear Admiral Mohammad Shariff was made second-in-command of the Eastern Command.

May 1971 army redeployment

Following the change in command, the 14th Division initially had its brigades posted at Comilla (53rd), Dhaka (57th), Rangpur (23rd) and Jessore (107th) before March 1971. During Operation Searchlight the 57th and the 107th moved to Jessore, while the 53rd had relocated to Chittagong. The Eastern Command moved 9th Division HQ (GOC Maj. Gen. Shawkat Riza) to Jessore, putting the 107th (Commander Brig. Makhdum Hayat, HQ Jessore) and the 57th (Commander Brig. Jahanzab Arbab, HQ Jhenida) under this division.[38] The 16th Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Nazar Hussain Shah) HQ moved to Bogra, which now included the 23rd (Commander Brig. Abdullah Malik, HQ Rangpur), the 205th (HQ Bogra) and the 34th (HQ Nator) Brigades.[39] The 14th Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Rahim) HQ remained at Dhaka, with its brigades at Mymensingh (27th), Sylhet (313th) and Comilla (117th). The 97th Independent Brigade was formed in Chittagong, while the 53rd Brigade was moved to Dhaka as a command reserve.[40]

Changes to Titu Mir

Brig. Gulam Jilani (later DG ISI), chief of staff for Gen. Niazi, reviewed the existing East Pakistan defence plan in June 1971[41] in light of the prevailing circumstances and left the plan basically unchanged. The following assumptions were made while re-evaluating the plan:[42]

- The main Indian thrust would come from the east, not the west as assumed in the earlier plan. The Indian army would attack to take control over the area between Sylhet and Chandpur, while a secondary attack would be aimed at Rangpur – Bogra and Mymensingh. At least five Indian infantry divisions (supported by an armoured brigade) would launch the attack.

- The insurgency situation would have improved, and the Eastern Command would be ready for both internal and external threats. If not, internal security measures have to be taken to contain the insurgency.

- All communication links would be fully functional and under government control, to facilitate troop movements.

Gen. Niazi added the following to the plan:[43]

- The Pakistani Army would launch attacks towards Tripura, Calcutta or the Shiliguri corridor if needed.

- Take over as much Indian territory as possible when the opportunity arises

No war games were conducted to factor in the new directives, or specific plans drawn up to attain these objectives. The revised plan was sent to Rawalpindi and approved in August 1971. During June and July, Mukti Bahini regrouped across the border with Indian aid through Operation Jackpot and sent 2,000–5,000 guerrillas across the border (the unsuccessful "Monsoon Offensive").[44][45][46]

Eastern offensive proposal

The Pakistan Army had built up an intelligence network to track Mukti Bahini infiltrations along the 2,700-kilometre (1,700 mi) border with India, so that they could be intercepted.[47] Gen. Niazi claimed to have suggested the following measures to Gen. Hamid (COS Pakistan Army) during his visit in June:[48]

- Attack the Mukti Bahini training camps across the border inside India in July 1971

- Create chaos within India by aiding the Mizo, Naga and Naxal insurgents, thus luring the Indian army away from Bangladesh

- Force the BSF units away from the border areas, sabotage the Farrakka barrage, launch offensive demonstrations against English Bazar and Balurghat, and bomb Calcutta.

- Reinforced by another squadron of warplanes and an additional infantry brigade, and bringing the existing infantry divisions in East Pakistan up to strength with required artillery and armour along with proper antiaircraft defence, it might be possible to occupy parts of Assam and West Bengal and create chaos in Calcutta.

- If reinforced with another two divisions (while reinforcing existing forces with required artillery and armour), it might be possible to carry the war onto Indian soil. With India deploying at least 15 divisions in the east to defeat the Pakistani force, its forces in the west could be defeated by the Pakistani army.

The Indian military at this time was vulnerable, with its main formations posted away from the East Pakistan border.[49] Col. Z.A. Khan (commander of the Special Services Group in East Pakistan) also advocated aggressive action against select Indian targets. General Hamid ruled out any provocations that might provoke Indian retaliation, while outlining the main objective of the Eastern Command: to keep the insurgency under control and prevent the formation of a Bangladesh government inside the province.[50] Gen. Niazi remained convinced that his scheme would have forced India to concede terms,[51] but at least one Pakistani source labels his proposal "sheer folly".[52]

The main plan remained unchanged until September 1971: Pakistani units were to fight a series of defensive battles before deploying to defend the Dhaka Bowl, but every inch of the province would not be defended. The Pakistan army occupied all the towns and fortified 90[53] of the 370 BoPs (half of the BoPs were destroyed by Indian shell fire by July 1971 to facilitate Mukti Bahini infiltration)[54] and deployed close to the border to halt Mukti Bahini activity.

Western Command strategy

The Pakistani high command began contemplating full-scale war with India to settle all issues as the insurgency in Bangladesh began to escalate after August;[55] with Mukti Bahini activities more aggressive and effective,[56] Pakistani forces were in disarray.[57] In doing so they had to contemplate fighting in the west and the east, and the ongoing insurgency. Since the defence of East Pakistan rested on overwhelming Pakistani success in the west (resulting in India withdrawing its forces in the east),[58][59] any formal war would also start when Pakistani forces in West Pakistan were ready to strike. In the summer of 1970, the western operational plan was revised. The following conclusions were drawn:[60]

- Pakistan can counterattack in retaliation for an Indian attack, or

- Launch preemptive strikes on Indian soil after GHQ approval is granted.

- A reserve force is needed to reinforce formations whenever needed, or to strike a decisive blow.

It was decided to keep part of the reserves to the north of the Ravi River and part to the south. The plan called for the formations near the border to seize favourable lodgement areas, to screen the main attack of the army. In September 1971 the plan was updated to include:[61]

- West Pakistan would retaliate immediately after the Indians launched an attack in East Pakistan. Pakistani formations would take over border areas without stretching their defensive capabilities; the idea was to create an impression that West Pakistan had launched a full-scale attack all along the border.

- The reserve force of one armoured and two infantry divisions from south of the Ravi would launch a full-scale attack and, if successful, the northern reserve force would join the assault.

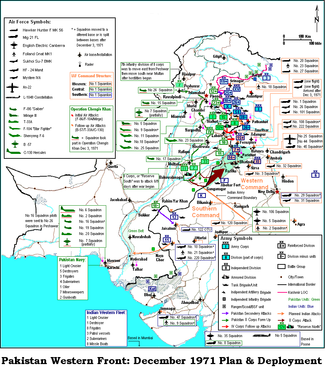

Western battle plan

The Pakistani army had fifteen divisions (including two armored divisions and in addition to several independent brigade groups) in West Pakistan in 1971. After transferring the 9th and 16th Divisions (known as "China Divisions" because these formations were given new Chinese equipment) to East Pakistan, they had a rough parity with the Indian army in infantry and a slight edge in armour. However, they could only hope to attack with 3:1 superiority in selected areas where surprise was vital. Pakistan had raised the 33rd Infantry Division, and had started to raise the 35th and the 37th Divisions to replace those sent to Bangladesh; these formations were active but not fully operational by November 1971. The Pakistan Army deployed ten infantry and two armoured divisions to face an Indian force of three corps (thirteen infantry, two mountain, one armoured division and several battle groups under the Indian Army Western and Southern Commands)[62] as follows:[63]

- The 12th (GOC Maj. Gen. Akbar Khan: six infantry brigades and six wings from the Frontier Corps) and the 23rd (GOC Maj. Gen. Iftikhar Khan Janjua: five infantry brigades, an independent armoured brigade and an armoured regiment) infantry divisions were deployed in Azad Kashmir. The 12th was to attack the Poonch sector, while the 23rd would attack the Chhamb sector initially and then push forward.

- In the Sialkot sector the 6th Armored Division (GOC Maj. Gen. M. Iskanderul Karim: two armoured brigades and two infantry battalions) was deployed along with the 8th (GOC Maj. Gen. Abdul Ali Malik: three brigades and two armoured regiments), the 15th (GOC Maj. Gen. Abid Ali Zahid: four brigades and eight independent armoured brigades) and the 17th (GOC Maj. Gen. R.D. Shamim: five infantry brigades) infantry divisions under I Corps (Commander Lt General Irshad Ahmed Khan). The 8th was to attack near Sakkargarh, in an attempt to draw off Indian reserves. These formations would then attempt to cut off Kashmir from the rest of India.[64] The 6th Armored and the 17th Divisions were designated "Reserve North".

- The 10th (GOC Maj. Gen. S.A.Z Naqvi: four infantry brigades) and the 11th (six infantry brigades) Infantry Divisions, along with the 3rd Independent Armored Brigade, was stationed in the Lahore sector under IV Corps (Commander Lt. Gen. Bahadur Shah). These formations were to launch diversionary attacks across the border and defend the central Punjab.

- The 1st Armored Division (two armoured brigades and one infantry battalion) and the 7th (GOC Maj. Gen. I.A. Akram: three infantry brigades) and the 33rd (GOC Maj. Gen. Ch. Nessar Ahmed: three infantry brigades) Infantry Divisions were posted south of the Ravi River; they were later joined by an independent infantry brigade under II Corps (Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan), headquartered in Multan. This force was designated "Reserve South". The 7th Infantry Division (initially based at Peshawar) was to move east to areas where it could support the 12th and 23rd Divisions as a diversion, then move and form up with the rest of II Corps south of the Sutlej.

- The 18th Infantry Division (GOC Maj. Gen. B.M. Mustafa: three infantry brigades) and two armoured regiments were deployed in Sindh, near Hydrabad.

Aside from these formations, Pakistan also had two independent artillery and two infantry brigade groups deployed on the border. The initial Pakistani plan was to launch diversionary attacks along the whole Indian border[65] to keep Indian reserve forces away from the main target areas, then attack the Poonch and Chhamb sectors and drive back the Indian forces while an infantry brigade (supported by an armoured regiment) pushed into Rajasthan towards Ramgarh. Once India had committed her reserves, II Corps would assemble south of the Sutlej (near Bahawalpur) and move east into India, swinging northeast towards Bhatinda and Ludhiana. Then IV Corps would push towards the Indian Punjab. Given that India had a slight edge in forces, Pakistani armoured units and the Pakistan Air Force needed to gain the upper hand quickly to ensure this plan succeeded.

The overall objective of the Pakistani ground assault was to capture enough Indian territory in the west to ensure a favourable bargaining position with India (should the Pakistani Eastern Command fail to repel the Indian attack on Bangladesh), and by forcing India to commit forces in the west and triggering the withdrawal of Indian forces from the east. From October 1971 onwards, Pakistani units began to take up positions along the border.

Importance of airstrikes

To negate Indian superiority in infantry (in addition to the 13 divisions deployed along the Pakistan border, it could call up the main reserve force if needed),[66] the Pakistan Air Force (OC Air Marshal A. Rahim Khan) needed to achieve air superiority on the western front. In 1971 it had 17 front-line squadrons[67] facing 26 Indian front-line squadrons (Chief of Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Pratap Chandra Lal, AOC-in-C, Western Air Command, Air Marshal M.M Engineer), while India deployed 12 squadrons (AOC-in-C, Eastern Air Command, Air Marshal H.C. Dewan) in the east (against one PAF squadron – CO Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan) and had another seven squadrons deployed elsewhere. Pakistani planners had assumed the PAF will be neutralized within 24 hours of IAF launching combat operations over East Pakistan,[68] and the Pakistani planners were aware that the Indian Air force would then be free to concentrate more aircraft in the west after deploying units to negate any Chinese moves. The PAF devised Operation Chengiz Khan to launch preemptive strikes on the IAF and neutralize its advantage at the onset of the war.

Naval role

The Pakistan Navy was in no position to counter the Indian threat, despite appeals to enhance naval capabilities over the years. The Pakistan Navy under commander-in-chief Vice Admiral Muzaffar Hasan (Fleet CO: Rear Admiral MAK Lodhi), with one cruiser, three frigates, five destroyers, four submarines and several gunboats, faced the Indian Western Fleet (FOCWF: Rear Admiral E. C. "Chandy" Kuruvila) consisting of one cruiser, eight frigates, one destroyer, two submarines and several patrol and missile boats in 1971.[69] The Pakistan Navy had no aggressive plans except sending the Ghazi to the Bay of Bengal to sink the Indian aircraft carrier INS Vikrant. On the Eastern Front, Indian Navy Eastern Fleet (Fleet CO: FOCEF Rear Admiral S. H. Sarma) consisted of one aircraft carrier, one destroyer, four frigates, 2 submarines and at least four gunboats, Pakistan Navy eastern fleey (CO: Rear Admiral Mohammad Shariff) had only one destroyer was active along with seven gunboats; therefore, it was impossible to conduct operations in the deep Bay of Bengal and he had planned to sit the war out.[70]

Problems in East Pakistan military

Pakistan Eastern Command HQ began to revise the operational plan from September onwards under the following assumptions:[71]

- India would launch a conventional attack in East Pakistan aiming to liberate a large area, transfer the Mukti Bahini and the refugees in the liberated area and seek recognition for the Bangladesh government in exile – thus involving the UN in the conflict.

- Mukti Bahini activity (which was supposed to be neutralised when the conventional attack took place, according to the old plan) had peaked, instead of being under control.

- The Army GHQ had ordered that the Mukti Bahini would be denied any area in East Pakistan to declare as "Bangladesh". Every inch of the province was to be defended from Bangladesh forces.

- Control over communications networks vital for the movement of troops and logistics[72] had collapsed due to the destruction of bridges, ferries and railway lines.[73]

Besides the above, the planners also had to factor in the status of the Pakistani forces in the province, logistical challenges presented by their deployment and the state of communications.

Manpower shortage

The East Pakistan garrison was reinforced with two infantry divisions in April 1971 to restore order and fight the insurgency. All divisional heavy equipment needed to fight a conventional war was left in the west.[74][75] A comparison of the deployed units between March and November shows:[76][77][78][79][80][81]

| March 1971 | June 1971 | Dec 1971 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Division HQ | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Ad hoc Division HQ | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Brigade HQ | 4 | 11 | 11 |

| Ad hoc Brigade HQ | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Infantry battalion | 16 | 30 | 35 + 4 |

| Artillery Regiment | 5 | 6 | 6 + 3 |

| Armored Regiment | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Heavy Mortar battery | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Commando Battalion | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Engineer Battalion | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Ack Ack Regiment | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EPR/EPCAF Wings | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| W Pakistan Ranger Wings | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Mujahid Battalion | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Razakars | 0 | 22,000 | 50,000 |

| Al Badr/Al Shams | 0 | 0 | 10,000 |

According to one estimate, the Eastern Command needed at least 250,000 personnel; it barely had 150,000 (50,000 regular soldiers) by November 1971.[82] To fill the manpower gap, the East Pakistan Civil Armed Force (EPCAF) (17 planes and approximately 23,000 personnel)[83] and Razakars (40,000 members, against a target of 100,0000)[84] were raised after June 1971. The armed police (11,000 members)[85] was also reorganised and bolstered with 5,000 West Pakistani personnel.[86] Therefore, the undermanned army was only fit for "Police action".[87] According to General Niazi, he had requested the following from GHQ in June 1971:

- Three medium- and one light-tank regiments were allocated for East Pakistan, out of which only the regiment already in the province was provided.[88] Also, two heavy- and one medium-artillery regiments were supposed to be sent but never arrived.[89]

- A squadron of fighter planes to back up the PAF unit in East Pakistan.[90] The PAF had plans to deploy a squadron of Shenyang F-6 planes in East Pakistan in 1971, but these were withdrawn because the PAF infrastructure in the province lacked the operational capacity to support housing two active squadrons.[91]

- Bringing the 9th and 16th Divisions up to strength by sending the artillery and engineering units left behind in West Pakistan and allocating corps artillery and armour for the Eastern Command (none of which was sent).[92]

The Pakistan GHQ had to weigh every request to resupply, reequip and reinforce the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan against the need of the West Pakistani forces, and did not have enough reserves of manpower and equipment for a long conflict.[93] The Eastern Command only deemed one of the three divisions fit for conventional warfare. Seven West Pakistan Ranger wings, five Mujahid battalions and a wing of Khyber Rifles, Tochi and Thal Scouts were sent to East Pakistan by November 1971.[94] Five infantry battalions were sent from West Pakistan in November. Al Badr and Al Shams units contributed another 5,000 men each.

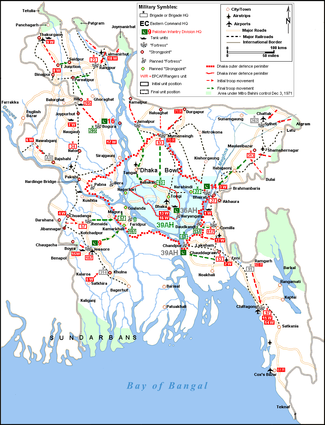

Ad hoc units

The lack of regular units also forced the Eastern Command to improvise in two ways: creating ad hoc formations to mimic regular army formations and mixing regular troops with paramilitary units. When Pakistani planners assumed India would launch its main attack in the east along the Akhaura – Brahmanbaria axis, it had no brigades available to cover this area. The 27th brigade from Mymensingh was moved to Akhaura, while two battalions from the brigade were detached to form the 93rd Brigade in Mymensingh.[95] Similarly, the 313th Brigade was moved from Sylhet to Maulavi Bazar and a battalion from the 313th was kept at Sylhet to form the nucleus of the 202nd ad hoc Brigade. The 14th Division (which covered both the Dhaka Bowl and the Eastern Sector except Chittagong) was given responsibility for the Eastern Sector only, and the 36th ad hoc Division (containing only the 93rd Brigade) was created to defend the Dhaka Bowl. Similarly, the 314th (for Khulna) and the Rajshahi ad hoc Brigades were created and deployed in September.[96] In mid-November, the 39th ad hoc Division was created to defend the Comilla and Noakhali districts from the 14th Division units deployed in those areas; the 14th was tasked to defend the Sylhet and Brahmanbaria areas only. The 91st ad hoc Brigade was created to defend the Ramgarh area north of Chittagong as part of the 39th Division in November. The ad hoc formations lacked the staff and equipment of regular formations.

Deception

General Niazi hoped that by creating five divisional HQs and simulating the signal traffic of numerous brigades, he would deceive the Indian Eastern Command into committing at least 15 infantry divisions and other assorted supporting forces in the east; this would mean India would have less to deploy in the west after retaining forces to use against any possible Chinese attacks from the north[97] (or at least deter the Indians from aggressive action).[98] While India did not deploy 15 divisions in the east, the measures deceived the Indian Eastern Command to some extent.[99]

Subtraction by addition

All paramilitary units (EPCAF/Razakar/Mujahid) were not up to army standards in terms of equipment and effectiveness, and the Eastern Command began to mix them with regular units to bolster their efficiency. Pakistani battalions were given two-thirds-companies of paramilitary units, while a company from some battalions was split into platoons and deployed at the BoPs or other places. Paramilitary personnel were attached to the platoons to bring these units up to company strength.[100] The army members were to stiffen these mixed units, but often the paramilitary members proved to be the weakest link.[101] Thus, some of the regular army units lost cohesion and effectiveness when their regular companies were detached from them.

Logistical woes

The underdeveloped state of the Bangladeshi communication infrastructures and the river system cutting through the plains was a formidable challenge to the movement of troops and supplies. General Niazi had ordered the Pakistan army to live off the land because of logistical difficulties,[102] and Maj. General A.O. Mittha (Quartermaster General, Pakistan Army) had recommended setting up river-transport battalions, cargo and tanker flotillas and increasing the number of helicopters in the province (none of which happened). Instead, the C-130 planes (which had played a crucial role during Operation Searchlight) were withdrawn from the province,[citation needed] diminishing the airlift capacity of the Pakistani forces further. The Mukti Bahini had sabotaged 231 bridges and 122 rail lines[103] by November 1971 (thus diminishing transport capacity to 10 percent of normal), and complicated the delivery of the daily minimum 600 tons of supplies to the army units.[104]

The Eastern Command staff kept the plan unchanged after the review; Pakistani troop deployments were not altered after the July appraisal. Pakistani units were kept at the border with the intention to withdraw them towards Dhaka after a series of defensive battles. The Eastern Command completed a final revision of the plan in October 1971, after both generals (Gul Hassan and Hamid) had visited the province.

Final plan: October 1971

General Niazi (along with General Jamshed (GOC EPCAF), General Rahim (2IC Eastern Command), Brig. Bakir (COS 3 Corps), Rear Admiral Sharif and Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan) reviewed the existing plan and updated it to factor in the manpower shortage, logistical difficulties, and the directive of the GHQ to defend every inch of East Pakistan.[105] The initial assumptions were:[106]

- The Indian Army Eastern Command would use 12 infantry/mountain divisions and an armoured brigade for the invasion under three corps commands, supported by Mukti Bahini and BSF units.

- The Mukti Bahini would step up its activities and try to occupy border areas, (if possible) occupying a large area of the province adjacent to the border.

- The PAF in East Pakistan would last only 24 hours against the IAF Eastern Contingent.[107]

- The main Indian assault would come from the west (opposite the Jessore sector), with a subsidiary attack from the east (opposite the Comilla sector).

- The naval detachment would move into the harbours once hostilities commenced.[108]

- The Indian strategic objective was to occupy as much of the province as quickly as possible to set up the Bangladesh government and the Mukti Bahini in the liberated area. Full occupation of the province was not the Indian goal.

Defensive considerations

The review committee analysed four strategic concepts when formulating the revised plan:[109]

- Deploying all available forces to defend the Dhaka Bowl along the Meghna, Jamuna and Padma Rivers. The Pakistan Army could use interior lines to switch forces as needed, and build up a strategic reserve while fighting on a narrower front. The disadvantage was that large tracts of areas outside the bowl would be lost without much effort from the invaders; India could set up the Bangladesh government easily inside the province. Also, it gave the Indians the opportunity to divert some of their forces to the west (thus threatening the balance of forces there) where a near-parity in forces was needed for a decisive result.

- Deploying in depth along the border, gradually moving towards the Dhaka Bowl. There were three problems with this concept:

- The state of the transport network and the transport capacity of the army

- Expected Indian air supremacy

- Mukti Bahini activity; all could combine to hinder movements.

- "Mobile Warfare" (positional defence): While the planners agreed that this was best possible course of action (given the terrain of the province), they also noted the chance of being chased and cornered by both the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army was also greater. Indian air dominance would also pose a threat to mobility, and might unhinge the strategy. Also, a large uncommitted reserve force was needed to execute this strategy properly; the Eastern Command had no such reserves, and could not create one unless reinfiorced by West Pakistan or by abandoning the "defending every inch of the province" concept.

- The "fortress" concept: Principal towns (especially those situated at communication hubs or an expected enemy thrust axis) would be converted into fortresses and defended to the last. This concept had two advantages: it did not call for the voluntary surrender of territory, concentrated forces and required limited mobility. Also, the planners felt India would have to neutralise the fortresses by capturing them through direct assaults or keeping sufficient forces back before pushing inland; they might not have sufficient forces to threaten the Dhaka Bowl if they bypassed the fortresses.

The fortress concept was adopted; the planners decided on a single defensive deployment of troops on the border, which went against the troop deployments advocated by earlier plans. This was done to stick to the GHQ order of not surrendering any territory to the Mukti Bahini. When devising troop deployments, the planners mixed political considerations with strategic ones and envisioned a forward-leaning defence in depth:[110][111][112][113]

- BoPs: East Pakistan had 370 border outposts along the Indian border, of which 90 had been occupied by Pakistani forces in an attempt to stop Mukti Bahini infiltration. Some of them had been fortified to withstand conventional assaults and airstrikes. EPCAF or regular soldiers were to man the outposts and offer initial resistance to enemy activity. Forward positions were to have supplies to last 7–15 days, and stockpiles for another 15–30 days in rear areas.[114]

- Strong points: These positions were to be chosen by the area division commanders according to the area terrain. Each strong point was to delay the enemy advance after troops have retreated from the BoPs and regular army units had concentrated around these positions. Flanking areas and communications would be guarded by paramilitary troops. Strong points stored munitions and supplies for up to 15 days.[115]

- Fortresses: These were major cities located on communications-network hubs. After delaying the enemy at the strong points, Pakistani units were to fall back on the fortresses and fight till the last. The fortresses were to contain rations to last 45 days, munitions for 60 days and be fortified like Tobruk in World War II.[116]

Defensive lines

Once the fortress defence was chosen, General Niazi and his staff designated the following cities as fortresses: Jessore, Jhenida, Bogra, Rangpur, Comilla and Bhairab Bazar (these were located on communication hubs), Jamalpur and Mymensingh (defending the northern perimeter of the Dhaka bowl), and Sylhet and Chittagong (independent defence areas). There were four lines of defence:

- The troops deployed on the border were the forward line. This was in front of the forward line envisioned in the X-Sundarbans exercise of 1967, which had deemed the whole border impossible to defend against a conventional attack.[117] The BoPs were all located on this line.

- Fortresses: All the fortresses were located on this line except Chittagong and Sylhet, which were to be independent defensive areas. This was the forward line of the 1967 X-Sundarbans plan; it was also deemed indefensible in its entirety in that exercise.

- Dhaka Outer Defense Line: Troops from the fortresses were to retreat to this line, which ran from Pabna in the west, to Bera and Sirajganj to the north and then to Mymensingh. From Mymensingh the line went south to Bhairab Bazar; from Bhairab it ran southwest along the Meghna to Daudkandi and Chandpur, then ran northwest along the Padma to the Madhumati, along the Madhumati back to Pabna. The fortresses of Bhairab and Mymensingh were part of this line. Pabna, Bera, Chandpur, Daudkandi and Faridpur would be turned into fortresses, while Kamarkhali, Goalanda, Nagarbari and Narshindi would be strong points. Faridpur and Narshindi were turned into strong points in December; the other sites were not built up.

- Dhaka Inner Defense Line: This ran from Manikganj in the west to Kaliakair, on to Tongi, then to Naryanganj and from Naryanganj back to Manikganj. This area was to have a fortress (Naryanganj) and strong points at Kalaikair and Tongi. None were developed by December 1971.

Having chosen the defence concept and defensive lines, the Pakistan Eastern Command outlined its course of action:

- Troops deployed on the border would hold on until ordered to retreat by the GOC. Later, Gen. Niazi forbade any retreat unless units had a casualty rate of 75 percent.

- Troops would "trade space for time" and fight a delaying action, while falling back to the nearest fortress.

- The fortress would be defended to the last (which was understood as the amount of time needed for Pakistan to deliver the knockout blow in the west).

- Troop formations would fall back to the Dhaka outer line to defend Dhaka as needed.

The divisional commanders were authorised to make plans for limited counterattacks in Indian territory to aid in their defensive objectives (one of which was to maintain control of the main roads leading into the territory).

Planned Pakistani deployments

Pakistani planners assumed (based on intelligence estimates) that an Indian force of 8 to 12 infantry divisions, an armoured brigade and the Mukti Bahini would launch the invasion of East Pakistan during the winter. The Pakistani army had divided the country into four sectors:[118][119][120]

Northern Sector: This area is to the north of the Padma and west of the Jamuna River, encompassing the Rajhshahi, Pabna, Bogra, Rangpur and Dinajpur districts. Pakistani planners were undecided on whether the Indian attack would come from the Siliguri Corridor south towards Bogra or on the Hili–Chilimari axis (from southwest to northeast) to cut the area in two. The division was deployed to counter both possibilities.[121]

The 16th Infantry Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Nazar Hussain Shah, HQ Bogra, then Nator) defended this area. It had the 29th Cavalry, two artillery regiments and a heavy mortar battery (the 117th Independent Mortar Battery), in addition to three infantry brigades: the 23rd (Commander Brig. S.A. Ansari, HQ Rangpur), the 205th (Commander Brig. Tajammul Hussain Malik, HQ Bogra) and the 34th (Brig. Mir Abdul Nayeem, HQ Nator). The general plan of defence was:

- The 23rd Brigade (8th, 25th, 48th Punjab and 26th Frontier Force Battalions) was to defend the area north of the Hili–Chilmari axis. The troops were to retreat to Dinajpur, Saidpur and Rangpur from the border areas, while Dinajpur, Saidpur, T-Junction and Thakurgaon were turned into strong points. The 48th Field regiment and one tank squadron (deployed near Thakurgaon) was also attached to this brigade. Three EPCAF wings, the 34th Punjab and a Mujahid battalion (the 86th) were also deployed in the brigade operational area. The area north of the Teesta River was a separate defence area where the 25th Punjab, 86th Mujahid, one-wing EPCAF and the independent heavy mortar battery were located.

- The 205th Brigade (the 4th and 13th Frontier Forces and the 3rd Baloch) would defend the area between Hili (a strong point) and Naogaon, then fall back to Bogra (a fortress) and hold out. Palashbari, Phulchari and Joyporhut were turned into strong points. A squadron of tanks (deployed near Naogaon, then Hili) along with the 80th Field Artillery Regiment and a mortar battery was also attached to this brigade.

- The 34th Brigade (the 32nd Punjab and 32nd Baloch) would look after the area between Rajshahi and Naogaon, and if needed would fall back to the Outer Dhaka defence line and defend from Pabna and Bera (both proposed fortresses). Three EPCAF wings supported this brigade. A squadron of tanks was deployed near Pakshi to guard the Hardinge bridge. In September, an ad hoc brigade was formed in Rajshahi to block the Padma from river operations.[122]

Western Sector: This area (south of the Padma and east of the Meghna) contained the Khulna, Jessore, Kushtia, Faridpur, Barisal and Patuakhali districts and was defended by the 9th Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Ansari) made up of two infantry brigades: the 107th (Commander Brig. Makhdum Hayat, HQ Jessore), covering the border from Jibannagar to the Sunderbans to the south, and the 57th (Commander Brig. Manzoor Ahmed, HQ Jhenida), which covered the border from Jibannagar to the Padma in the north. Two artillery regiments, a heavy mortar battery (the 211th) and a squadron of tanks were also part of the division. Pakistani planners assumed three likely axes of advance from the Indian army:[123][124]

- The main attack would come in the Calcutta – Banapol – Jessore axis.

- Another thrust would be made, either using the Krishnanagar – Darshana – Chuadanga axis or the Murshidabad – Rajapur – Kushtia axis.

The 107th Brigade (the 12th Punjab, the 15th and 22nd FF Battalions) was tasked with guarding the Benapol axis. This brigade was reinforced with the 38th FF in November, while the Third Independent Tank Squadron was destroyed at Garibpur on 22 November. In addition, the 55th Field Artillery Regiment and the heavy mortar battery was attached to the brigade and the 12th and 21st Punjab Battalions were deployed near its operational area.

The 57th Brigade (the 18th Punjab and 29th Baloch) was deployed to cover the Darshana and Meherpur areas. The 49th Field Artillery regiment was attached to this brigade, and the 50th Punjab reinforced the unit in November. To defend the Hardinge Bridge, a tank squadron was placed under the Eastern Command control near Kushtia. In September an ad hoc brigade – the 314th[125] (CO Col. Fazle Hamid, one Mujahib battalion and five companies each from EPCAF and Razakars) was created to defend the city of Khulna.[126] The 57th and 107th Brigades were to defend the border, then fall back to Jhenida and Jessore and prevent the Indians from crossing the Jessore–Jhenida road (which runs almost parallel to the border). The brigades also had the option to fall back across the Madhumati River (which formed part of the Dhaka outer defence line) and defend the area between Faridpur, Kamarkhali and Goalanda.

Dhaka Bowl: Pakistani planners anticipated a brigade size attack on the Kamalpur – Sherpur – Jamalpur axis, and another along the Haluaghat – Mymensingh axis.[127] They deemed this area impassable because of the hilly terrain on the Indian side and the Modhupur Jungle and Brahmaputra River to the north of Dhaka. The 27th Brigade initially was posted at Mymensingh, and the 53rd was in Dhaka. However, when the 27th Brigade was sent to Brahmanbaria, the 93rd Brigade (Commander Brig. Abdul Qadir Khan, HQ Mymensingh) was created from units of the 27th Brigade, and the 36th ad hoc Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Mohammad Jamshed Khan, HQ Dhaka) was created to replace the 14th Division. The order of battle of the 36th ad hoc Division was:

- The 93rd Brigade (the 33rd Punjab and 31st Baloch, plus the 70th and 71st West Pakistan Ranger wings), supported by the two EPCAF wings and the 83rd Independent Mortar Battery was responsible for the border area between the Jamuna river and Sunamganj. It developed strong points at Kamalpur, Haluaghat and Durgapur, while Jamalpur and Mymensingh were turned into fortresses. The course of the Brahmaputra River was designated the "line of no penetration".

- The 53rd Brigade (Commander Brig. Aslam Niazi, the 15th and 39th Baloch Battalions) was posted in Dhaka as command reserves and was responsible for the Dhaka inner defence line. Dhaka also had Razakar, EPCAF and other units that could be deployed for defence of the city. In November, Pakistani forces carried out a cleansing operation inside the Dhaka Bowl, but it had little effect in curbing Mukti Bahini activity.[128]

Eastern Sector: This sector included the Chittagong, Noakhali, Comilla and Sylhet districts. The anticipated lines of advance were:

- The Agartala – Akhaura – Bhairab Bazar axis would be the main thrust, with another attack coming towards Maulavi Bazar – Shamshernagar and a third near Comilla.

- The 14th Division (GOC: Maj. Gen. Rahim Khan, then Maj. Gen Abdul Majid Kazi) was initially HQed at Dhaka until the creation of the 36th ad hoc Division to cover the Dhaka Bowl, when its HQ moved to Brahmanbaria. The 14th Division initially had four brigades: the 27th (Commander Brig. Saadullah Khan, HQ Mymensingh), the 313th (Brig Iftikar Rana, HQ Sylhet), the 117th (Brig. Mansoor H. Atif, HQ Comilla) and the 53rd (Brig. Aslam Niazi, HQ Dhaka). After the review of September, it was decided to make the 14th responsible for the eastern sector encompassing the Sylhet, Comilla and Noakhali districts only. Chittagong was designated as an independent defence zone under control of the 97th Independent Brigade. Also, two ad hoc brigades were created: the 202nd and the 93rd, out of the units of the 14th Division. The division order of battle after September was:

- The 202nd ad hoc Brigade (Commander Brig. Salimullah, HQ Sylhet) was created by detaching the 31st Punjab from the 313th Brigade and incorporating elements of the 91st Mujahid and 12th Azad Kashmir Battalions. A wing each of Tochi and Thal Scouts and Khyber Rifles were also attached to the brigade, along with a battery from the 31st Field Regiment and the 88th Independent Mortar Battery. Sylhet was made a fortress, while this brigade was responsible for the border stretching from Sunamganj to the northwest of Sylhet, to Latu, to the east of that city.

- The 313th Brigade (Commander Brig. Rana, 30th FF and 22nd Baloch Battalions plus elements of the 91st Mujahid Battalion) moved to Maulavi Bazar (which was developed as a strong point), and the unit was responsible for the border between Latu and Kamalganj. After resisting the expected thrust along the Maulavi Bazar – Shamshernagar front, the brigade was to move south and link up with the 27th Brigade near Brahmanbaria. Gen Niazi also envisioned this brigade launching an assault inside Tripura, if possible.

- The 27th Brigade (33rd Baloch and 12th FF Battalions) was responsible for covering the border between Kamalganj and Kasba (just north of Comilla), and would block the expected main Indian axis of advance with strong points at Akhaura and Brahmanbaria. The Eighth Independent Armored Squadron (four tanks), 10 field guns from the 31st Field Regiment, a mortar battery along with an EPCAF wing, a Mujahid battalion, units from the 21st Azak Kashmir and 48th Punjab were also part of this brigade. Brig. Saadullah anticipated a three-pronged assault on his area around Akhaura, and planned to ultimately fall back to Bhairab (which was the nearest fortress, and part of the Dhaka outer-defense line).

- The 117th Brigade (the 23rd and 30th Punjab, 25th FF Battalions and 12th Azad Kashmir, minus elements) was HQed at Mainamati (north of Comilla), which was turned into a fortress. The 53rd Field Regiment and the 117th Independent Mortar Battery were attached to this brigade, along with three EPCAF wings and a troop of tanks. This brigade was responsible for the border between Kasba (to the north of Comilla) to Belonia in Noakhali. It was to concentrate near Comilla in the event of an Indian advance, then fall back to Daudkandi and Chandpur (which were part of the Dhaka outer-defense line and designated fortresses).

Chittagong: Independent defence zone

The 97th independent Infantry Brigade (Commander Brig. Ata Md. Khan Malik, HQ Chittagong) was to cover the Chittagong fortress and hill tracks. The 24th FF Battalion (along with two EPCAF wings and a Marine battalion) guarded Chittagong itself. The Second SSG was at Kaptai while the 60th and 61st Ranger Wings were posted at Ramgarh and Cox's Bazar, respectively.

Distribution of artillery and armour

The Eastern Command could not attach an artillery regiment to each of the infantry brigades, so only the 23rd, 205th, 57th, 107th, and 117th brigades were given an artillery regiment each. An artillery regiment (the 31st) was split between the 202nd ad hoc and the 27th Brigades, while elements of three other artillery regiments (the 25th, 32nd and 56th)[129] were proportionately distributed among the other brigades as required.[130] The 29th Cavalry was split into three independent squadrons among the 16th Division troops, while two other tank squadrons (one with the 107th Brigade and the other with the 117th Brigade) and two tank troops (one with the 36th ad hoc Division and the other with the 27th Brigade) were deployed.

Last-minute changes: November 1971

As events unfolded in Bangladesh and the Pakistani Army began to face ever-increasing difficulties, some officers at GHQ began to have second thoughts about the existing operational plan to defend East Pakistan. General Abdul Hamid, COS of the Pakistani Army, approved of the existing deployment of troops close to the border[131] but Lt. General Gul Hassan, CGS, had little faith in the plan Lt. Gen. Niazi had outlined to him in June.[132] Gen. Hassan supposedly tried to get the plan revised several times and insisted on abandoning the concept of defending every inch of the province, wanted the Eastern Command to redeploy regular units away from the border, fight for the BoPs and strong points on a limited scale and ensure Dhaka Bowl had enough reserves instead of the gradual withdrawal of forces to Dhaka outlined in the existing plan.[133] However, GHQ Rawalpindi approved in October 1971 only with the following adjustments:[134]

- Pakistani units to launch offensive action against English Bazar in West Bengal, if possible

- Commando action to destroy Farakka barrage should be considered

- Defense of Chittagong should be formed around one infantry battalion

- Dhaka to be defended at all costs

These suggestions were incorporated in the plan without change. From September onwards Pakistani forces had begun to fortify positions with concrete bunkers, anti-tank ditches, land mines and barbed wires. Spiked bamboo was also used, and some areas were flooded to hinder enemy movements.[135] Engineering battalions were sent to construct fortified positions, although some of the strong points and fortresses (especially those inside the Dhaka outer-defense line) remained incomplete.

Final reinforcements and directives

In November, Gen. Niazi sent Maj. Gen Jamshed and Brig. Bakir Siddiqi to Rawalpindi to request two more divisions as reinforcements (as well as all the heavy equipment left behind by the 9th and 16th Divisions for East Pakistan). The GHQ promised to send 8 infantry battalions and an engineer battalion;[136] only five battalions were sent to East Pakistan because the GHQ probably could not spare anything else.[137][138] The first two units (the 38th FF and 50th Punjab) were given to the 9th Division. The next three battalions were split up and sent as reinforcements to various areas, as needed.[139] The last three battalions were to replace the 53rd Brigade as command reserves in Dhaka, but never arrived from West Pakistan. At the meeting, the Eastern Command was told to continue its "political mission" (i.e. prevent territory from falling into Mukti Bahini hands), although by this time 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of territory had fallen into their hands. Gen Niazi claims this order was never withdrawn,[140] and Gen. Hassan suggested that Gen. Hamid never altered the plan Gen. Niazi had submitted in October (including the deployment of troops near the border).[141] The GHQ never commented on the deployment plan,[142] while others claim the Eastern Command failed to readjust its deployments despite advice from GHQ.[143]

39th ad-hoc Division

In November 1971, Rawalpindi GHQ warned the Eastern Command that the Indian army would launch the main attack from the east. Gen. Niazi and Gen. Rahim identified the axis of the main attack as:[144]

- South of Comilla, towards Mudafarganj and Chandpur

- East of Belonia, from Ramgarh south towards Chittagong

Gen Niazi split the 14th Division and transferred the 117th Brigade to the newly created 39th ad hoc Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Rahim, HQ Chandpur), which also included the 53rd (Commander Brig. Aslam Niazi, HQ Feni) and the 91st ad hoc Brigade (Commander Brig. Mian Taskeen Uddin, HQ Chittagong). The deployment of the troops was:

- The 117th Brigade was to cover the area from Kasba to the north of Comilla to Chauddagram in the south. After fighting at the border, the force was to redeploy around the Mainamati fortress and then fall back to defend Daudkandi (which was on the Dhaka outer-defense line).

- The 53rd Brigade (the 15th and 39th Baloch, plus elements of the 21st Azad Kashmir Battalion) was transferred from the command reserve to guard the border from Chaddagram to Belonia. This brigade was to fall back to Chandpur, a fortress located on the Dhaka outer-defense line after its initial defence of Feni and Laksham.

- The 91st ad hoc Brigade (the 24th FF battalion, one Ranger and one Mujahid battalion and elements of the 21st Azad Kashmir) was to guard the Belonia – Ramgarh area. It was to fall back to Chittagong after defending the area. The 48th Baloch was sent to the 97th Brigade in Chittagong after the 24th FF was given to the 91st Brigade.

Summary

The final plan was created to meet both political and strategic objectives, and its success depended on two crucial factors: predicting the possible Indian axis of advance correctly, and the ability of the Pakistani troops to fall back to their designated areas in the face of Indian air superiority and Mukti Bahini activity. The Pakistani Eastern Command was fighting a holding action cut off from reinforcements and without any reserves to counter unforeseen developments, and its ultimate success lay in Pakistan defeating India in the west. If any of the factors deviated from the assumed norm of the plan, the Eastern Command was without the resources to win on its own. The Pakistani army had been fighting the insurgency nonstop for eight months and was severely fatigued[145] and short of supplies; in addition, the deployment near the border had robbed them of the manoeuvrability needed for a flexible defence.[146]

See also

- Mitro Bahini order of battle

- Pakistan Army order of battle, December 1971

- Military plans of the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Timeline of the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts

References

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 128

- ^ Ali 1992, pp. 118–119

- ^ Niazi 1998, pp. 131–132

- ^ Khan 1993, pp. 301, 307

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 123

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 124–125

- ^ Jacob 1997, p. 73

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 124–125

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp47

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp49

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp47, pp51

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 114

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 1q2

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 114

- ^ Islam 2006, pp. 309–310

- ^ ^ Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat Richard H. Shultz, Andrea Dew: "The Martial Races Theory had firm adherents in Pakistan and this factor played a major role in the under-estimation of the Indian Army by Pakistani soldiers as well as civilian decision makers in 1965."^

- ^ ^ Library of Congress studies.

- ^ Cohen 2004, p. 103

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp55

- ^ Shafiullah 1989, p. 31

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp55

- ^ Matinuddin 1994, p. 337

- ^ Shafiullah 1989, p. 32

- ^ §The Man of Honor and Integrity: Admiral Syed Mohammad Ahsan, Unified Commander of Pakistan Armed Forces in East Pakistan." (in English), Witness to Surrender., Inter Services Public Relations, Siddique Salik,, pp. 60–90, ISBN 984-05-1374-5.

- ^ Ali 1992, pp. 114–119

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 14

- ^ Ali 1992, pp. 117–118

- ^ Ali 1992, pp. 115–116

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 114

- ^ Qureshi 2002, pp. 119–120

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp73

- ^ Matinuddin, Kamal (1994), "§The Turning Point: Admiral's Resignation, the decision fills with regrets." (in English), Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis 1968 – 1971, Lahore Wajidalis, pp. 170–200, ISBN 969-8031-19-7.

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 63

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 89

- ^ Khan 1993, p. 237

- ^ Siddiqui, A. R. (December 1977). "1971 Curtain-Raiser". Defence Journal. III (12): 3.

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 90

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 126

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 241

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 126

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 85

- ^ Qureshi 2002, p. 121

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 89

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 100

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara' 71, pp64 – pp65

- ^ Khan 1973, p. 125

- ^ Qureshi 2002, p. 109

- ^ Niazi 1998, pp. 96–98

- ^ Singh 1980, p. 65

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 99

- ^ Niazi 1998, pp. 98–99, 282

- ^ Matinuddin 1994, pp. 342–343, 347–350

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 101

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara' 71, pp45

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, pp100, pp104

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara' 71, pp118 – pp119

- ^ Khan, Maj. Gen. Fazal Muqeem, Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership, pp128

- ^ Cloughley, Brian, A History of the Pakistan Army, Oxford University Press 1999, pp155 – pp184

- ^ Hamdoor Rahman Commission Report, Part IV, Chapters II and III

- ^ Hassan Khan, Lt. Gen. Gul, Memories of Lt. Gen. Gul Hassan Khan, pp291 – pp293

- ^ Hassan Khan, Lt. Gen. Gul, Memories of Lt. Gen. Gul Hassan Khan, pp283 – pp286

- ^ Major Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp188

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, pp310

- ^ Major Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp231

- ^ Qureshi, Maj. Gen. Hakeem A., The 1971 Indo –Pak War A Soldier's Narrative, pp137- pp139

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp231

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp188

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 132

- ^ Rahman, Md. Khalilur, Muktijuddhey Nou-Abhijan, pp23 – pp24

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 135

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 127

- ^ Qureshi 2002, p. 121

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 124–125

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 90

- ^ Khan 1993, p. 308

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 90, 105

- ^ Niazi 1998, pp. 105–109

- ^ Jacob 1997, pp. 184–190

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp196 – pp197

- ^ Qureshi 2002, p. 20

- ^ Arefin, A.S.M. Shamsul, Muktijudder Prekkhapotey Bektir Aubsthan, pp342 – pp344

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 101

- ^ Niazi 1998, pp. 105–106

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 105

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 106

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 96

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 88

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 87

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 136

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 98

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 123

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 109

- ^ Hamdoor Rahman Commission Report, Part IV, Chapters V

- ^ Jacob 1997, pp. 184–190

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 126

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 126, 139, 149, 167

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 98

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 127

- ^ Jacob 1997, p. 84

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 115

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 126

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 93

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 104

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara' 71, pp118 – pp119

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 110

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 123–126

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 132

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 134

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 124

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 123–126

- ^ Riza 1977, pp. 121–122

- ^ Matinuddin 1994, pp. 342–350

- ^ Khan 1973, pp. 107–112

- ^ Qureshi 2002, p. 124

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 161

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 124

- ^ Ali 1992, pp. 117–121

- ^ Jacob 1997, pp. 184–190

- ^ Matinuddin 1994, pp. 348–350

- ^ Riza 1977, pp. 134–159

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 149

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 149

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 140

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp243 – pp244

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 113

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 139

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 181

- ^ Khan 1973, pp. 127–129

- ^ Arefin, A.S.M. Shamsul, Muktijudder Prekkhapotey Bektir Aubsthan, pp343

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 114

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 119

- ^ Khan 1993, pp. 296–299

- ^ Khan 1993, pp. 296–299, 309–313

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 125

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 113

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 132

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 100

- ^ Khan 1993, pp. 307–309

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 127

- ^ Niazi 1998, p. 132

- ^ Khan 1993, pp. 295–299, 300–309

- ^ Ali 1992, p. 119

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 128

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 171

- ^ Riza 1977, p. 133

- ^ Khan 1973, pp. 128–129

Sources

- Ali, Rao Farman (1992). How Pakistan Got Divided. Lahore: Jung Publishers. OCLC 28547552.

- Cloughley, Brian (1999). A History of the Pakistan Army: Wars and Insurrections (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579015-3.

- Cohen, Stephen P. (2004). The Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1502-1.

- Islam, Rafiqul (2006) [First published 1974]. A Tale of Millions: Bangladesh Liberation War-1971. Dhaka: Ananna. ISBN 978-984-432-419-0.

- Jacob, JFR (1997). Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation. Dhaka: University Press Limited. ISBN 978-984-05-1395-6.

- Khan, Fazal Mukeem (1973). Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership. National Book Foundation. OCLC 976643179.

- Khan, Gul Hassan (1993). Memoirs of Lt. Gen. Gul Hassan Khan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577447-4.

- Matinuddin, Kamal (1994). Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis 1968 – 1971. Lahore: Wajidalis. ISBN 978-969-8031-19-0.

- Niazi, A.A.K. (1998). The Betrayal of East Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577727-7.

- Salik, Siddiq (1997). Witness to Surrender. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577761-1.

- Qureshi, Hakeem Arshad (2002). The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldiers Narrative. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579778-7.

- Riza, Shaukat (1977). The Pakistan Army 1966–71. Dehra Dun, India: Natraj. ISBN 978-81-85019-61-1.

- Shafiullah, K. M. (1989). Bangladesh at War. Dhaka: 978-984-08-0109-1. ISBN 978-984-08-0109-1.

- Singh, Sukhwant (1980). India's Wars Since Independence. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House. ISBN 0-7069-1057-5.

Further reading

- Rahman, Md. Khalilur (2006). Muktijuddhay Nou-Abhijan. Shahittha Prakash. ISBN 984-465-449-1.

- Jones, Owen Bennet (2003). Pakistan Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10147-3.

- Shamsul Arefin, A.S.M (1998). History, standing of important persons involved in the Bangladesh war of liberation. University Press Ltd. ISBN 984-05-0146-1.

- Nasir Uddin (2005). Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata. Agami Prokashoni. ISBN 984-401-455-7.

- Islam, Rafiqul (1995). Muktijuddher Itihas. Kakoli Prokashoni. ISBN 984-437-086-8.

- Hussain Raja, Khadim (1999). A stranger in my own country, East Pakistan, 1969-1971. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-547441-1.