Euston Road

Euston Road in 2008 | |

| Former name(s) | New Road |

|---|---|

| Namesake | Euston Hall |

| Length | 1.1 mi (1.8 km)[1] |

| Postal code | W1, NW1 |

| Coordinates | 51°31′39″N 0°07′53″W / 51.5275°N 0.131389°W |

| West end | Great Portland Street |

| East end | Pentonville Road |

| Construction | |

| Inauguration | September 1756 |

Euston Road is a road in Central London that runs from Marylebone Road to King's Cross. The route is part of the London Inner Ring Road and forms part of the London congestion charge zone boundary. It is named after Euston Hall, the family seat of the Dukes of Grafton, who had become major property owners in the area during the mid-19th century.

The road was originally the central section of New Road from Paddington to Islington which opened in 1756 as London's first bypass. It provided a route along which to drive cattle to Smithfield Market avoiding central London. Traffic increased when major railway stations, including Euston, opened in the mid-19th century and led to the road's renaming in 1857. Euston Road was widened in the 1960s to cater for the increasing demands of motor traffic, and the Euston Tower was built around that time. The road contains several significant buildings including the Wellcome Library, the British Library and the St Pancras Renaissance London Hotel.

Geography

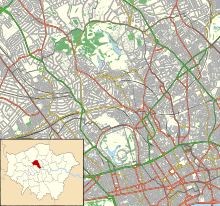

The road starts as a continuation of the A501, a major road through Central London, at its junction with Marylebone Road and Great Portland Street. It meets the northern end of Tottenham Court Road at a large junction with an underpass, and it ends at King's Cross with Gray's Inn Road. The road ahead to Islington is Pentonville Road.[1] The road is part of the London Inner Ring Road and on the edge of the London congestion charge zone. Drivers are not charged for travelling on the road but may be if they turn south into the zone during its hours of operation.[2]

King's Cross and St Pancras railway stations are at the eastern end of the road, and Euston railway station is further west.[3] The position of these three railway termini on Euston Road, rather than in a more central position further south, is a result of the recommendations of the 1846 Royal Commission on Metropolitan Railway Termini that sought to protect the West End districts a short distance south of the road.[4]

Euston Tower is a landmark on the road and The British Library is just to the west of St Pancras station. The old and new headquarters of the Wellcome Trust are on its south side.[5] From west to east the road passes Regent's Park, Great Portland Street, Warren Street, Euston Square, Euston and King's Cross St Pancras tube stations.[1] Bus routes 30 and 205 run along the entire extent of Euston Road from Great Portland Street to King's Cross.[6]

History

18th–19th century

Before the 18th century, the land along which Euston Road runs was farmland and fields. Camden Town was a village retreat for Londoners working in the city.[7] Euston Road was originally part of New Road, promoted by Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton and enabled by an Act of Parliament passed in 1756.[3] Construction began in May that year, and it was open to traffic by September.[8]

The road provided a new drovers' road for moving sheep and cattle to Smithfield Market avoiding Oxford Street and Holborn, and ended at St John's Street, Islington.[3] It provided a quicker route for army units to reach the Essex coast when there was a threat of invasion, without passing through the cities of London and Westminster,[8] and was a barrier between the increasing urban sprawl that threatened to reach places such as Camden Town.[7] The Capper family, who lived on the south side of the proposed route, opposed its construction and complained their crops would be ruined by dust kicked up by cattle along the route. Capper Street, a side street off Tottenham Court Road, is named after the family.[3] A clause in the 1756 Act stipulated that no buildings should be constructed within 50 feet (15 m) of the road, with the result that most of the houses along it lay behind substantial gardens. During the 19th century the law was increasingly ignored.[8]

Euston station opened on the north side of New Road in July 1837. It was planned by Robert Stephenson on the site of gardens called Euston Grove, and was the first mainline station to open in London. Its entrance, designed by Philip Hardwick, cost £35,000 (now 4,017,000) and had the highest portico in London at 72 feet (22 m). The Great Hall opened in 1849 to improve accommodation for passengers, and a statue of Stephenson's father George was installed in 1852.[9] The Dukes of Grafton had become the main property owners in the area, and in 1857 the central section of the road, between Osnaburgh Street and Kings Cross, was renamed Euston Road[10] after Euston Hall, their country house. The eastern section became Pentonville Road, the western Marylebone Road.[8] The full length of Euston Road was dug up so that the Metropolitan Railway could be built beneath it using a cut-and-cover system and the road was then relaid to a much higher standard.[7][11] The new Anglican church of St Luke's Church opened on Euston Road in 1861; it was shortly afterwards demolished and replaced by St Pancras railway station, which opened in 1867, with the fronting Midland Grand Hotel following in 1873.[12] The Euston station complex was controversially demolished in 1963 to accommodate British Rail's facilities. The replacement building opened in 1968, and now serves 50 million passengers annually.[13]

Tolmers Village was in the tiny triangle (less than 2 hectares (4.9 acres)) on the north side of Euston Road between Hampstead Road and North Gower Street. It was built in the early 1860s over a former reservoir to provide affordable middle-class terraced housing but its proximity to a main road and the Euston Station complex meant it ultimately catered for the working classes. By 1871, around 5,000 residents were housed in a 12-acre (4.9 ha) area. The estate continued to expand throughout the early 20th century in a piecemeal fashion, and attracted Greek, Cypriot and Asian immigrants following World War II.[14] In the 1970s, the estate came under threat from property developers who wanted to demolish it and build offices, which led to demonstrations and protests, including supporters from University College. The plans were cancelled, but the estate was still bulldozed and replaced by tower blocks.[14][3]

20th–21st century

The area around the junction with the Tottenham Court Road suffered significant bomb damage during the Second World War. Patrick Abercrombie's contemporary Greater London Plan called for a new ring road around Central London called the 'A' Ring, but post-war budget constraints meant that a medley of existing routes were improved to form the ring road, including Euston Road.[15] An underpass to avoid the junction with the Tottenham Court Road was proposed by the London County Council (LCC) in 1959,[16] with construction beginning in 1964.[17] The property developer Joe Levy was keen to develop buildings in the area and bought various properties. When the LCC refused planning permission because of the underpass development, Levy, who had outline planning permission, insisted the council pay him £1 million if they wanted to compulsorily purchase the site. Over the next four years, Levy bought properties along the north side of Euston Road, and an agreement was reached so that the council built the underpass and he built a complex of two tower blocks with office shops and apartments, the Euston Tower.[18]

The tower attracted a number of significant tenants, including Inmarsat[19] and the independent radio station Capital Radio. The ITV broadcaster Thames Television's corporate headquarters were nearby at No. 306–316 Euston Road from 1971 to 1992 when the station closed. That building was demolished in 1994 and redeveloped when Thames, now a production company, moved all operations to Teddington Studios.[20][21]

In the early-21st century, the Greater London Authority commissioned a plan to improve the road from the architectural firm, Terry Farrell and Partners. The original study proposed removing the underpass (which was subsequently cancelled) and providing a pedestrian crossing and removing the gyratory system connecting the Tottenham Court Road and Gower Street. The scheme was approved by the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone as "the start of changing the Marylebone to Euston road from a highway into a series of linked public spaces."[22] The pedestrian crossing opened in March 2010.[23] Livingstone's successor, Boris Johnson, favours keeping the Euston Road underpass and declared it to be a good place to test his nerves when cycling around London.[24]

In 2015, Transport for London announced its intention to close one lane in each direction on Euston Road between 2020 and 2026 to accommodate work on High Speed 2. The decision was condemned by Camden Borough Council as it could affect business and cost more than £1 billion in lost revenue. The AA said the works were the largest ever proposed in London and would affect far more than local traffic due to its Inner Ring Road status.[25]

Notable buildings

About halfway along Euston Road, at the junction with Upper Woburn Place, is St Pancras New Church, built in 1822.[3] Designed by William and Henry Inwood and costing around £90,000 (now £10,359,000), it was the most expensive religious building in London since St Paul's Cathedral, completed in the previous century.[26] Almost opposite is Euston Road fire station, built 1901–2, in an Arts and Crafts style by Percy Nobbs. The Shaw Theatre opened at No. 100–110 in 1971, in honour of George Bernard Shaw. It was refurbished in 2000 as part of an adjacent Novotel development. The Keith Grant sculpture at the theatre's front was removed but was subsequently reinstated after protests.[27]

The New Hospital for Women moved to No. 144 Euston Road in 1888, and was rebuilt by J.M. Brydon two years later. It housed 42 beds and was staffed entirely by women, which made it a comfortable environment for patients with gynaecological problems. It was renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in 1918 following the death of the hospital's founder, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman in England to qualify as a doctor of medicine. The Euston Road premises closed in 1993, its services transferred to University College Hospital.[28] The current hospital is at No. 235.[29] The Wellcome Trust, a private medical research charity, was established in 1936 and has premises at No. 183 and No. 210 Euston Road. Its library holds about half a million books, including more than 6,000 Sanskrit manuscripts and the largest collection of Hindi and Punjabi medical documents in Europe. Its objects were transferred on permanent loan to the Science Museum in 1976.[5] The University College London Hospital's archives are at No 250 Euston Road.[30]

In late 1898, 189 Euston Road (Where the Wellcome Collection is at present) was the location of a Mosque run by Hajie Mohammad Dollie who opened London's first Mosque previously at 97 Albert Street, Camden Town in 1895.[31]

The Midland Grand Hotel, fronting St Pancras station, was designed by George Gilbert Scott. It was built mainly with red bricks with a tower at one end and a spire at the other. It closed in 1935 and was repeatedly threatened with demolition until it was Grade I listed in 1967. It was used as offices until a major restoration in the early 1990s.[32] The hotel reopened as the St Pancras Renaissance London Hotel in 2011.[33]

Camden Town Hall, formerly St Pancras Town Hall, opened in 1937.[3] The Euston Theatre of Varieties was based at No. 37–43. It was renamed the Regent Theatre in 1922, and converted to a cinema in 1932. It was demolished in 1950 so that the town hall could be extended.[3]

The headquarters of the Religious Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, is at Friends House, No. 173 Euston Road. It was built between 1925–7 and holds the society's library dating back to 1673, including George Fox's journal covering the foundation of Pennsylvania.[34] Euston Road School was opened at No. 314 in 1934 by William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Claude Rogers to encourage artwork in an atmosphere different from traditional art schools. The school struggled and closed by the start of World War II. It was demolished in the early 1960s; the cover shot of the Beatles' Twist and Shout EP was of its remains after demolition.[35][3]

The British Library moved to No. 96 Euston Road in 1999 into a new complex designed by Colin St John Wilson and opened by Queen Elizabeth II. It was built using more than ten million bricks and has a floor area of 112,000 square metres (1,210,000 sq ft). Although it was given a critical reception by architectural critics, visitors have enjoyed the welcoming entrance and praised its internal arrangements. Around 16,000 people visit each day. [36]

Cultural references

In Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray, the characters Sibyl and James Vane live at a "shabby lodgings" on Euston Road.[37]

The street is a property in the United Kingdom edition of the board game Monopoly, which features famous London areas on its gameboard. It is a part of the pale blue set, along with Pentonville Road, and The Angel, Islington.[38]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c "383 Euston Road to 30 Euston Road". Google Maps. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Congestion Charging in London". BBC London. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weinreb et al 2008, p. 277.

- ^ "1846 Royal Commission". Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b Weinreb et al 2008, p. 995.

- ^ "Central London Bus Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Walford, Edward (1878). "Euston Road and Hampstead Road". Old and New London. 5. London: 301–309. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Timbs 1867, pp. 613–4.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, pp. 277–278.

- ^ "Judd Place West". UCL Bloomsbury Project. UCL. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Palmer, Samuel (1870). St Pancras. London. pp. 242–4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Weinreb et al 2008, pp. 804–5.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 278.

- ^ a b "Tolmers Village". Hidden London. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Roads (London), Development Plan". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 7 April 1955. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Traffic Tunnel for Euston Road". The Times. No. 54497. 26 June 1959. p. 7. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Euston Road Underpass". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 22 November 1966. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Hill, Dave (23 August 2015). "How Euston Road got wider, taller and deeper and Joe Levy got rich". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Godwin, Matthew (5 December 2007). "Interview with Roy Gibson" (PDF). Oral History of Europe in Space. European Space Agency. p. 5. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Television & Radio (Report). Independent Broadcasting Authority. 188. p. 172.

- ^ Aylett, Glenn (3 September 2005). "The Studios". Transdiffusion Broadcasting System. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Farrell's Euston Road plan moves a step closer". Building Magazine (41). 2005. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "First new crossing along the Euston Road in 10 years" (Press release). Camden London Borough Council. March 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Boris Johnson: the interview". The London Magazine. 24 June 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Chandler, Mark (22 October 2015). "Euston Road closure to cost businesses 'millions' warn critics". Evening Standard. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Davies, Andrew John (31 October 1995). "Site Unseen : The caryatids, St Pancras New Church, London". The Independent. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 833.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, pp. 268.

- ^ "Contact University College Hospital". Camden London Borough Council. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Our History". University College London Hospital. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ "A Tour Guide Has Discovered London's Oldest Mosque". 23 February 2017.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, pp. 548–9, 804–5.

- ^ Easton, Mark (5 May 2011). "A monument to the British craftsman". BBC Blogs. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 309.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 227.

- ^ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Raby, Peter (1988). Oscar Wilde. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-521-26078-7.

- ^ Moore 2003, p. 210.

Sources