European pond turtle

| European pond turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| European pond turtle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Emys |

| Species: | E. orbicularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Emys orbicularis | |

| |

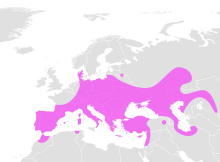

| The range of the European pond turtle | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis), also called commonly the European pond terrapin and the European pond tortoise, is a species of long-living freshwater turtle in the family Emydidae.[3] The species is endemic to the Western Palearctic.

Subspecies

The following 14 subspecies are recognized as being valid.[2]

- Emys orbicularis capolongoi Fritz, 1995 – Sardinian pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis colchica Fritz, 1994 – Colchis pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis eiselti Fritz, Baran, Budak & Amthauer, 1998 – Eiselt's pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis fritzjuergenobstii Fritz, 1993 – Obst's pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis galloitalica Fritz, 1995 – Italian pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis hellenica (Valenciennes, 1832) – Western Turkey pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis hispanica Fritz, Keller & Budde, 1996 – Spanish pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis iberica Eichwald, 1831 – Kura Valley pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis ingauna Jesu, Piombo, Salvidio, Lamagni, Ortale & Genta, 2004

- Emys orbicularis lanzai Fritz, 1995 – Corsican pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis luteofusca Fritz, 1989 – Central Turkey pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis occidentalis Fritz, 1993 – North African pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758) – common European pond turtle

- Emys orbicularis persica Eichwald, 1831 – Eastern pond turtle

A trinomial authority in parentheses indicates that the subspecies was originally described in a genus other than Emys.

Etymology

The subspecific name eiselti is in honor of Viennese herpetologist Josef Eiselt (1912–2001).[4]

The subspecific name fritzjuergenobsti is in honor of German herpetologist Fritz Jürgen Obst (1939–2018).[4]

The subspecific name lanzai is in honor of Italian herpetologist Benedetto Lanza.

Range and habitat

E. orbicularis is found in southern, central, and eastern Europe, West Asia and parts of Mediterranean North Africa. In France, there are six remaining populations of significant size; however, they appear to be in decline. This turtle species is the most endangered reptile of the country.[5] In Switzerland, the European pond turtle was extinct at the beginning of the twentieth century but reintroduced in 2010.[5] In the early post-glacial period, the European pond turtle had a much wider distribution, being found as far north as southern Sweden and Great Britain,[6] where a reintroduction has been proposed by the Staffordshire-based Celtic Reptile & Amphibian, a group specialising in the care, research, and rehabilitation of native European and British herpetiles.[7] A trial reintroduction has been initiated, restoring the species back to its Holocene-native East Anglian Fens, Brecks and Broads.[8] In 2004, the European pond turtle was found in the Setomaa region of Estonia.[9]

Fossil evidence shows that E. orbicularis and Testudo hermanni were both present in Sardinia during the Pleistocene, but molecular evidence suggests the extant populations of both species on the island were introduced in modern times.[10]

E. orbicularis prefers to live in wetlands that are surrounded by an abundance of lush, wooded landscape. They also feed in upland environments.[11] They are usually considered to be only semi-aquatic (similar to American box turtles), as their terrestrial movements can span 1 km (0.62 mi). They are, occasionally, found travelling up to 4 km (2.5 mi) away from a source of water.[11]

Biology

Morphology

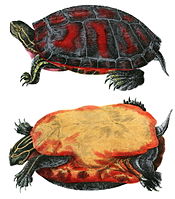

The European pond turtle is a medium-sized turtle, and its straight carapace length varies quite a bit across its geographic range, from 12 to 38 cm (4.7 to 15.0 in). The carapace is dark brown to blackish, with a hint of green. The head and legs are spotted with yellow. The plastron is yellowish.

An important factor that affects the development of E. orbicularis is temperature and thermal conditions. It has been reported that differential growth rates of the same species occur, including variation of body size and clutch size, because of varying temperatures in certain areas.[12] Due to evident patterns of sexual dimorphism, E. orbicularis adult males are always found to be smaller than females. In males, smaller plastra offer them a wider mobility compared to females. In females, due to their differential diet and foraging habits, there may be a correlation to an adaptive effect on their skull and head morphology.[12]

Diet

E. orbicularis eats a mixed diet of plants and animal matter that can increase the efficiency of its digestive process.[11] It has been reported that an adult's diet starts from a carnivorous diet and progresses to a more herbivorous diet as it ages and grows in size. This is similar to other omnivore emydid turtles.[11] As E. orbicularis grows in age and becomes an adult, the amount of plant material consumption increases during the post breeding period. E. orbicularis may prefer less energetic food after the breeding season, a period of time where most of its energy is spent to recover from reproduction.[11]

Nesting

Most freshwater turtles lay their eggs on land, typically near a water source, but some species of Emys have been found to lay their eggs no less than 150 m (490 ft) from water.[3] The search for nesting areas, by adult females, can last several hours to several days. Once an appropriate site is found, females take their time with the construction of the nest, painstakingly excavating a small pit out of the soft substrate purely by usage of her small forelimbs. Once satisfied with the depth of the nest, she will turn around (facing away from the nest) and proceed with egg-laying, gently dropping the eggs down and into a small pile. This process varies in duration; laying can take merely half an hour or upwards of several hours, depending on weather, interference by other animals, humans, etc. When laying is complete (and still facing away from the nest), the female turtle will use her back limbs this time, to cover and close the nest. This is another variable routine which can take up to another four hours.[13]

Nest fidelity is a characteristic that is unique to female European pond turtles—selecting a nesting site based on its ecological characteristics—and then returning there for future laying, so long as the site has not changed.[3] E. orbicularis females tend to look to a new nesting site if there are visible changes to the original nest’s surroundings, or because of dietary and metabolic changes. If an E. orbicularis female must change from nest to nest, she will typically select a site in relatively close proximity.[3] In addition, females may also lay eggs in an abandoned nesting site if the conditions are an improvement, and deemed to be better suited for egg survival. If the environmental conditions of a nesting site change, this may influence the development of the eggs, the survival of the hatchlings and/or their sex ratio. Due to unforeseen ecological changes, such as thick vegetation growing over a season (and blocking sun to the nest), a nest site may become inadequate for incubating eggs. Females that do not exhibit nesting fidelity, and continue to lay in the same area for long periods of time—even with the ecological changes—may end up producing more male offspring, as the cooler and darker conditions promote more males developing.[3] Since the sex of these turtles is temperature-dependent, a change in temperature may produce a larger number of males or females which may upset the sex ratio.[3]

Mortality

Climate has an effect on the survival of E. orbicularis hatchlings. Hatchlings are only able to survive under favorable weather conditions, but due to regular annual clutch sizes and long lifespan, E. orbicularis adults, along with many freshwater turtles, balance out loss of hatchlings due to climate.[13]

The species E. orbicularis has become rare in most countries even though it is widely distributed in Europe. The building of roads and driving of cars through natural habitats is a possible factor that threatens the populations of the European pond turtle. Road networks and traffic often carry complex ecological effects to animal populations such as fragmenting natural habitats and creating barriers for animal movement. Mortality on the road is most likely due to females selecting nests near roads which places a potential danger for the hatchlings as well. Hatchlings that wander too closely to roads are more likely to be killed and put the future population in danger. Although the possibility of roads being a major causation for the mortality of E. orbicularis is a rare phenomenon, long-term monitoring is necessary.[13]

Introduced exotic species such as Trachemys scripta scripta and T. s. elegans, known commonly as Florida turtles, also put in danger the native Emys species in many parts of Spain (and possibly in other parts of southern Europe), since these exotic turtles are bigger and heavier than the native pond turtles.[14][15] The usual life span of E. orbicularis is 40–60 years. It can live over 100 years, but such longevity is rare.

Parasites

E. orbicularis hosts several species of parasites, including Haemogregarina stepanovi, monogeneans of the genus Polystomoides, vascular trematodes of the genus Spirhapalum, and many nematode species.[citation needed]

Human impact

Historically, E. orbicularis had been maintained as pets; however, this practice has been restricted due to protection laws. Ownership of wild caught specimens is prohibited. Only registered captive bred specimens may be owned by private individuals. Due to human impact, the European pond turtle has been found to be relocated in areas distant from its origin. However, it is possible to localize and indicate a region of origin with genetic testing.[16]

The population of E. orbicularis in Ukraine is listed under Appendix III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[17]

See also

References

- ^ Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (2016) [errata version of 1996 assessment]. "Emys orbicularis ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T7717A97292665. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T7717A12844431.en. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 181–184. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. ISSN 1864-5755.

- ^ a b c d e f Mitrus, Sławomir (2006). "Fidelity to nesting area of the European pond turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758)". Belgian Journal of Zoology. 136 (1): 25–30.

- ^ a b Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Emys orbicularis eiselti, p. 81; E. o. fritzjuergenobsti, p. 193).

- ^ a b Perrot, Julien (2016). "Dans la peau d'une tortue ". La Salamandre (235): 20-45. (especially pages 32-33). (in French).

- ^ "New research into prehistoric pond terrapins | Research and discussion | Blog | CGO Ecology Ltd". www.cgoecology.com. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ Griffiths, Sarah. "Can a long-lost turtle help to restore Britain's wetlands?". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (2023-07-07). "European pond turtle could return to British rivers and lakes". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Lõugas, Lembi. "Sookilpkonn Setomaal". eestiloodus.horisont.ee (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ^ Zoboli, Daniel; Georgalis, Georgios L.; Arca, Marisa; Tuveri, Caterinella; Carboni, Salvatore; Lecca, Luciano; Pillola, Gian Luigi; Rook, Lorenzo; Villani, Mauro; Chesi, Francesco; Delfino, Massimo (2022-07-29). "An overview of the fossil turtles from Sardinia (Italy)". Historical Biology. 35 (8): 1484–1513. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2098488. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 251185149.

- ^ a b c d e Ficetola, Gentile Francesco; De Bernardi, Fiorenza (2006). "Is the European "pond" turtle Emys orbicularis strictly aquatic and carnivorous?". Amphibia-Reptilia. 27 (3): 445–447. doi:10.1163/156853806778190079.

- ^ a b Zuffi, M. A. L.; Celani, A.; Foschi, E.; Tripepi, S. (2007). "Reproductive strategies and body shape in the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis) from contrasting habitats in Italy". Italian Journal of Zoology. 271 (2): 218–224. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00212.x.

- ^ a b c Trakimas, G.; Sidaravicius, J. (2008). "Road mortality threatens small northern populations of the European pond turtle, Emys orbicularis". Acta Herpetologica. 3 (2): 161–166.

- ^ "La tortuga de Florida amenaza la fauna de la desembocadura del río Millars ". 2 November 2005. (in Spanish).

- ^ "La tortuga de Florida, especie exótica invasora ". (in Spanish).

- ^ Velo-Antón, Guillermo; Godinho, Raquel; Ayres, César; Ferrand, Nuno; Rivera, Adolfo Cordero (2007). "Assignment tests applied to relocate individuals of unknown origin in a threatened species, the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 28 (4): 475–484. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.2852. doi:10.1163/156853807782152589.

- ^ "Appendices I, II and III". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 21 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

Further reading

- Arnold EN, Burton JA (1978). A Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe. (With 351 illustrations, 257 in colour by D.W. Ovenden). London: Collins. 272 pp. + Plates 1-40. ISBN 0-00-219318-3. (Emys orbicularis, p. 93 + Plate 14, figure 1 + Map 48).

- Boulenger GA (1889). Catalogue of the Chelonians, Rhynchocephalians, and Crocodiles in the British Museum (Natural History). New Edition. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). x + 311 pp. + Plates I-III. (Emys orbicularis, pp. 112–114).

- Linnaeus C (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata. Stockholm: L. Salvius. 824 pp. (Testudo orbicularis, new species, p. 198). (in Latin).