Ephrem the Syrian

Ephrem the Syrian | |

|---|---|

Mosaic in Nea Moni of Chios (11th century) | |

| |

| Born | c. 306 Nisibis, Syria, Roman Empire |

| Died | 373 Edessa, Osroene, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast | List

|

| Attributes | Vine and scroll, deacon's vestments and thurible; with Saint Basil the Great; composing hymns with a lyre |

| Patronage | Spiritual directors and spiritual leaders |

Ephrem the Syrian[a] (/ˈiːfrəm, ˈɛfrəm/; c. 306 – 373), also known as Saint Ephrem, Saint Ephraim (/ˈiːfriəm/), Ephrem of Edessa or Aprem of Nisibis, was a prominent Christian theologian and writer who is revered as one of the most notable hymnographers of Eastern Christianity. He was born in Nisibis, served as a deacon and later lived in Edessa.[1][2]

Ephrem is venerated as a saint by all traditional Churches. He is especially revered in Syriac Christianity, both in East Syriac tradition and West Syriac tradition, and also counted as a Holy and Venerable Father (i.e., a sainted monk) in the Eastern Orthodox Church, especially in the Slovak tradition. He was declared a Doctor of the Church in the Roman Catholic Church in 1920. Ephrem is also credited as the founder of the School of Nisibis, which, in later centuries, was the centre of learning of the Church of the East.

Ephrem wrote a wide variety of hymns, poems, and sermons in verse, as well as prose exegesis. These were works of practical theology for the edification of the Church in troubled times. Some of these works have been examined by feminist scholars who have analyzed the incorporation of feminine imagery in his texts. They also examine the performance practice of all-women choirs singing his madrāšê, or his teaching hymns. Ephrem's works were so popular that, for centuries after his death, Christian authors wrote hundreds of pseudepigraphal works in his name. He has been called the most significant of all of the fathers of the Syriac-speaking church tradition.[3] In Syriac Christian tradition, he is considered patron of the Syriac Aramaic people.

Life

Ephrem was born around the year 306 in the city of Nisibis (modern Nusaybin, Turkey), in the Roman province of Mesopotamia, that was recently acquired by the Roman Empire.[4][5][6][7] Internal evidence from Ephrem's hymnody suggests that both his parents were part of the growing Christian community in the city, although later hagiographers wrote that his father was a pagan priest.[8] In those days, religious culture in the region of Nisibis included local polytheism, Judaism and several varieties of the Early Christianity. Most of the population spoke the Aramaic language, while Greek and Latin were languages of administration. The city had a complex ethnic composition, consisting of "Assyrians, Arabs, Greeks, Jews, Parthians, Romans, and Iranians".[9]

Jacob, the second bishop of Nisibis,[10] was appointed in 308, and Ephrem grew up under his leadership of the community. Jacob of Nisibis is recorded as a signatory at the First Council of Nicea in 325. Ephrem was baptized as a youth and almost certainly became a son of the covenant, an unusual form of Syriac proto-monasticism. Jacob appointed Ephrem as a teacher (Syriac malp̄ānâ, a title that still carries great respect for Syriac Christians). He was ordained as a deacon either at his baptism or later.[11] He began to compose hymns and write biblical commentaries as part of his educational office. In his hymns, he sometimes refers to himself as a "herdsman" (ܥܠܢܐ, 'allānâ), to his bishop as the "shepherd" (ܪܥܝܐ, rā'yâ), and to his community as a 'fold' (ܕܝܪܐ, dayrâ). Ephrem is popularly credited as the founder of the School of Nisibis, which, in later centuries, was the centre of learning of the Church of the East.[citation needed]

In 337, Emperor Constantine I, who had legalised and promoted the practice of Christianity in the Roman Empire, died. Seizing on this opportunity, Shapur II of Persia began a series of attacks into Roman North Mesopotamia. Nisibis was besieged in 338, 346 and 350. During the first siege, Ephrem credits Bishop Jacob as defending the city with his prayers. In the third siege, of 350, Shapur rerouted the River Mygdonius to undermine the walls of Nisibis. The Nisibenes quickly repaired the walls while the Persian elephant cavalry became bogged down in the wet ground. Ephrem celebrated what he saw as the miraculous salvation of the city in a hymn that portrayed Nisibis as being like Noah's Ark, floating to safety on the flood.[citation needed]

One important physical link to Ephrem's lifetime is the baptistery of Nisibis. The inscription tells that it was constructed under Bishop Vologeses in 359. In that year, Shapur attacked again. The cities around Nisibis were destroyed one by one, and their citizens killed or deported. Constantius II was unable to respond; the campaign of Julian in 363 ended with his death in battle. His army elected Jovian as the new emperor, and to rescue his army, he was forced to surrender Nisibis to Persia (also in 363) and to permit the expulsion of the entire Christian population.[12] Ephrem declined being ordained a bishop by feigning madness, because he regarded himself unworthy for it.[13][14][15]

Ephrem, with the others, went first to Amida (Diyarbakır), eventually settling in Edessa (Urhay, in Aramaic) in 363.[16] Ephrem, in his late fifties, applied himself to ministry in his new church and seems to have continued his work as a teacher, perhaps in the School of Edessa. Edessa had been an important center of the Aramaic-speaking world, and the birthplace of a specific Middle Aramaic dialect that came to be known as the Syriac language.[17] The city was rich with rivaling philosophies and religions. Ephrem comments that orthodox Nicene Christians were simply called "Palutians" in Edessa, after a former bishop. Arians, Marcionites, Manichees, Bardaisanites and various gnostic sects proclaimed themselves as the true church. In this confusion, Ephrem wrote a great number of hymns defending Nicene orthodoxy. A later Syriac writer, Jacob of Serugh, wrote that Ephrem rehearsed all-female choirs to sing his hymns set to Syriac folk tunes in the forum of Edessa. In 370 he visited Basil the Great at Caesarea, and then journeyed to the monks of Egypt. As he preached a panegyric on St. Basil, who died in 379, his own death must be placed at a later date.[clarification needed] After a ten-year residency in Edessa, in his sixties, Ephrem succumbed to the plague as he ministered to its victims. He died in 373.[18][19]

Language

Ephrem wrote exclusively in his native Aramaic language, using the local Edessan (Urhaya) dialect, that later came to be known as the Classical Syriac.[8][20] Ephrem's works contain several endonymic (native) references to his language (Aramaic), homeland (Aram) and people (Arameans).[21][22][23][24][25] He is therefore known as "the authentic voice of Aramaic Christianity".[26]

In the early stages of modern scholarly studies, it was believed that some examples of the long-standing Greek practice of labeling Aramaic as "Syriac", that are found in the Cave of Treasures,[27][28] can be attributed to Ephrem, but later scholarly analyses have shown that the work in question was written much later (c. 600) by an unknown author, thus also showing that Ephrem's original works still belonged to the tradition unaffected by exonymic (foreign) labeling.[29][30][31][32]

One of the early admirers of Ephrem's works, theologian Jacob of Serugh (d. 521), who already belonged to the generation that accepted the custom of a double naming of their language not only as Aramaic (Ārāmāyā) but also as "Syriac" (Suryāyā),[33][34][35][36] wrote a homily (memrā) dedicated to Ephrem, praising him as the crown or wreath of the Arameans (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ), and the same praise was repeated in early liturgical texts.[37][38] Only later, under the Greek influence already prevalent in the works of the middle fifth century author Theodoret of Cyrus,[39] did it became customary to associate Ephrem with Syriac identity, and label him only as "the Syrian" (Koinē Greek: Ἐφραίμ ὁ Σῦρος), thus blurring his Aramaic self-identification, attested by his own writings and works of other Aramaic-speaking writers, and also by examples from the earliest liturgical tradition.[citation needed]

Some of those problems persisted up to the recent times, even in scholarly literature, as a consequence of several methodological problems within the field of source editing. During the process of critical editing and translation of sources within Syriac studies, some scholars have practiced various forms of arbitrary (and often unexplained) interventions, including the occasional disregard for the importance of original terms, used as endonymic (native) designations for Arameans and their language (ārāmāyā). Such disregard was manifested primarily in translations and commentaries, by replacement of authentic terms with polysemic Syrian/Syriac labels. In previously mentioned memrā, dedicated to Ephrem, one of the terms for Aramean people (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ / Arameandom) was published correctly in original script of the source,[40] but in the same time it was translated in English as "Syriac nation",[41] and then enlisted among quotations related to "Syrian/Syriac" identity,[42] without any mention of Aramean-related terms in the source. Even when noticed and corrected by some scholars,[43][44][45] such replacements of terms continue to create problems for others.[46][47][48]

Several translations of his writings exist in Classical Armenian, Coptic, Old Georgian, Koine Greek and other languages. Some of his works are extant only in translation (particularly in Armenian).[citation needed]

Writings and authorship

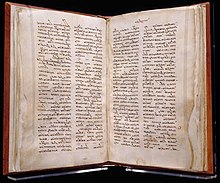

Manuscripts

According to the Catalogues of Syriac Manuscripts in the British Library published by Forshall & Rosen (1839) and Wright (1870–72), there are "ninety or so manuscripts which contain works by or attributed to Ephraem."[49]

| 5th century | 6th century | 7th century | 8th century | 9th century | 10th century | 11th century | 12th century | 13th century |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mss. | 14 mss. | 4 mss. | 11 mss. | 19 mss. | 7 mss. | 12 mss. | 8 mss. | 11 mss. |

Hymns

Over four hundred hymns attributed to Ephrem still exist.[according to whom?] Granted that some have been lost, Ephrem's productivity is not in doubt.[according to whom?] The church historian Sozomen credits Ephrem with having written three million verses.[49] Ephrem combines in his writing a threefold heritage: he draws on the models and methods of early Rabbinic Judaism, he engages skillfully with Greek science and philosophy, and he delights in the Mesopotamian/Persian tradition of mystery symbolism.[citation needed]

The most important of his works are his lyric, teaching hymns (ܡܕܖ̈ܫܐ, madrāšê). These hymns are full of rich, poetic imagery drawn from biblical sources, folk tradition, and other religions and philosophies. The madrāšê are written in stanzas of syllabic verse and employ over fifty different metrical schemes. The form is defined by an antiphon, or congregational refrain (ܥܘܢܝܬܐ, 'ûnîṯâ), between each independent strophe (or verse), and the refrain's melody mimics that of the opening half of the strophe.[50] Each madrāšâ had its qālâ (ܩܠܐ), a traditional tune identified by its opening line. All of these qālê are now lost. It seems that Bardaisan and Mani composed madrāšê, and Ephrem felt that the medium was a suitable tool to use against their claims.[50]

The madrāšê are gathered into various hymn cycles. In the CSCO critical edition of Beck et al. (1955–1975), these have been given standardised names and abbreviations.[51] By the year 2000, English translations had been published for the following:[52]

- 52 hymns On Virginity[52]

- 28 hymns On the Nativity[52]

- 15 hymns On Paradise[52]

- 4 hymns Against [Emperor Caesar] Julian[52]

- Carmina Nisibena or On Nisibis[52]

- On the Church[52]

- On Lent[52]

- On the Paschal Season[52]

- Against Heresies[52]

Some of these titles do not do justice to the entirety of the collection (for instance, only the first half of the Carmina Nisibena is about Nisibis).[citation needed] Bates (2000) remarked: "[Various] collections of Ephrem's hymns [...] appear to be randomly assembled by later editors and named for the subject of the first hymn in the collection only".[52]

Particularly influential were his Hymns Against Heresies.[53] Ephrem used these to warn his flock of the heresies that threatened to divide the early church. He lamented that the faithful were "tossed to and fro and carried around with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness and deceitful wiles" (Eph 4:14).[54] He devised hymns laden with doctrinal details to inoculate right-thinking Christians against heresies such as docetism. The Hymns Against Heresies employ colourful metaphors to describe the Incarnation of Christ as fully human and divine. Ephrem asserts that Christ's unity of humanity and divinity represents peace, perfection and salvation; in contrast, docetism and other heresies sought to divide or reduce Christ's nature and, in doing so, rend and devalue Christ's followers with their false teachings.[citation needed]

Authenticity of hymns On the Nativity

Some of these hymn cycles provide implicit insight into Ephrem's perceived level of comfort with incorporating feminine imagery into his writings.[55] According to J. Barrington Bates (2000), the 28 hymns of the cycle On the Nativity centered around Mary and had the clearest pervasive theme of Ephrem's hymn cycles.[55] An example of feminine imagery is found when Ephrem writes of the baby Jesus: "He was lofty but he sucked Mary's milk and from his blessings all creation sucks."[56] However, Edmund Beck rejected their authenticity in 1956,[57][58] adding that in the writings that can be reasonably attributed to Ephrem, he said very little about Mary as intercessor.[59] Sebastian Brock similarly questioned their authenticity when he published English translations of a small group of them in 1984; when he published a full translation of these and other Syriac Marian hymns in 1994, he entirely rejected Ephrem's authorship, attributing them to the 5th and 6th centuries instead.[58] Cornelia Horn (2015) accepted Brock's conclusion.[58] Bates (2000) had a more mixed assessment of these 28 madrashe, arguing that only 12 of them were not authentic: "The core of this particular collection [On the Nativity] is a set of sixteen hymns probably gathered and entitled "lullabyes" (in Syriac, nwsrť) by Ephrem himself. Four other hymns were added by an anonymous sixth-century editor, and eight others on the subject of the birth of Christ included by a modern scholar."[56]

Authenticity of hymns On Epiphany

The most complete, critical text of writings attributed to Ephrem was compiled between 1955 and 1979 by Dom Edmund Beck, OSB, as part of the Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium (CSCO).[60] Beck's 1959 critical edition of the madrashe (hymns) and mêmrê (homilies) memre attributed to Ephrem led to much scholarly debate on the authenticity of the madrashe known as On Epiphany, as Ephrem was certainly not familiar with Epiphany as a feast celebrating Jesus' bapitism on 6 January.[60] Unlike in Europe, where the Nativity of Jesus was celebrated on 25 December, but the baptism of Jesus would evolve into a separate feast called "Epiphany" on 6 January, there was only one Christian feast celebrated in winter in the time and place where Ephrem lived, namely the Nativity on 6 January, when baptism was also performed.[61] A 1956 paper written by Beck himself therefore warned researchers not to base their reconstructions of Ephrem's baptismal theology on the contents of these madrashe, given the fact that many of the hymns presuppose that Epiphany and Nativity were two separate feasts celebrated two weeks apart, thereby challenging Ephrem's authorship.[62] While the oldest surviving manuscripts of Ephrem's hymns date to the 6th century and contain hymns on the Nativity that Beck thought were certainly authentic, the contested hymns On Epiphany are missing from them.[61] They do not appear in manuscripts until much later, in the 9th century, suggesting that they were interpolated.[61] Scholars have largely accepted Beck's arguments that the collection as a whole was established after the 4th century, and that some hymns in them were not written by Ephrem, or at least not in the form that they have been preserved in, but that other hymns should nevertheless be considered authentic.[63]

Performance practices and gender

The relationship between Ephrem's compositions and femininity is shown again in documentation suggesting that the madrāšê were sung by all-women choirs with an accompanying lyre. These women's choirs were composed of members of the Daughters of the Covenant, an important institution in historical Syriac Christianity, but they weren't always labeled as such.[64] Ephrem, like many Syriac liturgical poets, believed that women's voices were important to hear in the church as they were modeled after Mary, mother of Jesus, whose acceptance of God's call led to salvation for all through the birth of Jesus.[65] One variety of the madrāšê, the soghyatha, was sung in a conversational style between male and female choirs.[65] The women's choir would sing the role of biblical women, and the men's choir would sing the male role. Through the role of singing Ephrem's madrāšê, women's choirs were granted a role in worship.[64]

Further writings

Ephrem also wrote verse homilies (ܡܐܡܖ̈ܐ, mêmrê). These sermons in poetry are far fewer in number than the madrāšê. The mêmrê were written in a heptosyllabic couplets (pairs of lines of seven syllables each).[citation needed]

The third category of Ephrem's writings is his prose work. He wrote a biblical commentary on the Diatessaron (the single gospel harmony of the early Syriac church), the Syriac original of which was found in 1957. His Commentary on Genesis and Exodus is an exegesis of Genesis and Exodus. Some fragments exist in Armenian of his commentaries on the Acts of the Apostles and Pauline Epistles.[citation needed]

He also wrote refutations against Bardaisan, Mani, Marcion and others.[66][67]

Symbols and metaphors

Ephrem's writings contain a rich variety of symbols and metaphors. Christopher Buck gives a summary of analysis of a selection of six key scenarios (the way, robe of glory, sons and daughters of the Covenant, wedding feast, harrowing of hell, Noah's Ark/Mariner) and six root metaphors (physician, medicine of life, mirror, pearl, Tree of life, paradise).[68]

Pseudepigraphy and misattributions

Ephrem's meditations on the symbols of Christian faith and his stand against heresy made him a popular source of inspiration throughout the church. There is a huge corpus of Ephrem []pseudepigraphy]] and legendary hagiography in many languages. Some of these compositions are in verse, often mimicking Ephrem's heptasyllabic couplets.[citation needed] Syriac churches still use many of Ephrem's hymns as part of the annual cycle of worship. However, most of these liturgical hymns are edited and conflated versions of the originals.[citation needed] Another one of the works attributed to Ephrem was the Cave of Treasures, written in Syriac, but by a much later, unknown author, who lived at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century.[69]

Greek Ephrem

"It is a mark of Ephraem's enormous reputation that such an extensive corpus of works in Greek was gathered under his name. Where no Syriac original has survived, the question of authenticity arises. (...) The Greek works may not be so much translations as adaptations in the spirit of Ephraem using his favourite images. A widely held judgment is that the corpus is 'sporadically authentic'."

There is a very large number of works by "Ephrem" extant in Greek. In the literature this material is often referred to as "Greek Ephrem", or Ephraem Graecus ("Ephrem the Greek", as opposed to the real Ephrem the Syrian), as if it was by a single author. This is not the case, but the term is used for convenience. Some texts are in fact Greek translations of genuine works by Ephrem, but most are not.[70] Ephrem is attributed with writing hagiographies such as The Life of Saint Mary the Harlot (extant in Greek and Latin), though this credit is called into question.[71] The best known of these writings is the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, which is recited at every service during Great Lent and other fasting periods in Eastern Christianity.[72][73]

There has been very little critical examination of any of these works. They were edited uncritically by Assemani, and there is also a modern Greek edition by Phrantzolas.[74] Amongst scholars, there is a broad consensus that the Greek corpus attributed to Ephrem is only 'sporadically authentic'.[70]

Latin Ephrem and other languages

There are also works by "Ephrem" in Latin, Slavonic and Arabic. "Ephrem Latinus" is the term given to Latin translations of "Ephrem Graecus". None is by Ephrem the Syrian. "Pseudo-Ephrem Latinus" is the name given to Latin works under the name of Ephrem which are imitations of the style of Ephrem Latinus. One example is the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ephraem, extant in one Latin and one Syriac version.[citation needed] Also attributed to Ephrem are the Parenesis or "precepts", found in the 10th-century Rila fragments and the early 13th-century Kyiv Caves Patericon, translated into Old Church Slavonic.[citation needed]

Veneration as a saint

Soon after Ephrem's death, legendary accounts of his life began to circulate. One of the earlier "modifications" is the statement that Ephrem's father was a pagan priest of Abnil or Abizal. However, internal evidence from his authentic writings suggest that he was raised by Christian parents.[75]

Ephrem is venerated as an example of monastic discipline in Eastern Christianity. In the Eastern Orthodox scheme of hagiography, Ephrem is counted as a Venerable Father (i.e., a sainted monk). His feast day is celebrated on 28 January and on the Saturday of the Venerable Fathers (Cheesefare Saturday), which is the Saturday before the beginning of Great Lent.[76]

On 5 October 1920, Pope Benedict XV proclaimed Ephrem a Doctor of the Church ("Doctor of the Syrians").[77]

The most popular title for Ephrem is Harp of the Spirit (Syriac: ܟܢܪܐ ܕܪܘܚܐ, Kenārâ d-Rûḥâ). He is also referred to as the Deacon of Edessa, the Sun of the Syrians and a Pillar of the Church.[78]

His Roman Catholic feast day of 9 June conforms to his date of death. For 48 years (1920–1969), it was on 18 June, and this date is still observed in the Extraordinary Form.[79]

Ephrem is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on June 10.[80]

Ephrem is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 9 June.[81]

Translations

- Sancti Patris Nostri Ephraem Syri opera omnia quae exstant (3 vol), by Peter Ambarach Rome, 1737–1743.

- E. Beck, Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Hymen De Nativitate (Epiphania), CSCO 186/187, Leuven 1959, 144–191 (131–177). (in German).

- French translation based on the edition of Beck: Ephrem le Syrien. Hymnes sur l'Êpiphanie. Hymnes baptismales de l'Orient syrien. Introduction, traduction du texte syriaque, notes et index par François Cassingena, o.s.b ., Spiritualité orientale, no 70, Abbaye de Bellefontaine, Bégrolles-en-Mauges 1997.

- Ephrem the Syrian Hymns, introduced by John Meyendorff, translated by Kathleen E. McVey. (New York: Paulist Press, 1989) ISBN 0-8091-3093-9

- St. Ephrem Hymns on Paradise, translated by Sebastian Brock (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1990). ISBN 0-88141-076-4

- Saint Ephrem's Commentary on Tatian's Diatessaron: An English Translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709 with Introduction and Notes, translated by Carmel McCarthy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

- St. Ephrem the Syrian Commentary on Genesis, Commentary on Exodus, Homily on our Lord, Letter to Publius, translated by Edward G. Mathews Jr., and Joseph P. Amar. Ed. by Kathleen McVey. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1994). ISBN 978-0-8132-1421-4

- St. Ephrem the Syrian The Hymns on Faith, translated by Jeffrey Wickes. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2015). ISBN 978-0-8132-2735-1

- San Efrén de Nísibis Himnos de Navidad y Epifanía, by Efrem Yildiz Sadak Madrid, 2016 (in Spanish). ISBN 978-84-285-5235-6

- Saint Ephraim the Syrian Eschatological Hymns and Homilies, translated by M.F. Toal and Henry Burgess, amended. (Florence, AZ: SAGOM Press, 2019). ISBN 978-1-9456-9907-8

See also

Notes

- ^ Classical Syriac: ܡܪܝ ܐܦܪܝܡ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, romanized: Mār ʾAp̄rêm Sūryāyā, Classical Syriac pronunciation: [mɑr ʔafˈrem surˈjɑjɑ]; Koinē Greek: Ἐφραὶμ ὁ Σῦρος, romanized: Efrém o Sýros; Latin: Ephraem Syrus; Amharic: ቅዱስ ኤፍሬም ሶርያዊ

References

- ^ Brock 1992a.

- ^ Brock 1999a.

- ^ Parry 1999, p. 180.

- ^ Karim 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Possekel 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Lipiński 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 179-235.

- ^ a b Brock 1992a, p. 16.

- ^ McVey 1989, p. 5.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 220-222.

- ^ Parry 1999, p. 180-181.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 215, 217, 223.

- ^ "Saint Ephrem". 9 June 2022. p. Franciscan Media. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Venerable Ephraim the Syrian". p. The Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Harp of the Holy Spirit: St. Ephrem, Deacon and Doctor of the Church". p. The Divine Mercy. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Russell 2005, p. 195-196.

- ^ Healey 2007, p. 115–127.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (2007). Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second Series Volume IV Anthanasius. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-514-7.

- ^ Darcy, Peter (2021-02-27). "St. Ephrem's Marvelous Sermon on the Cross of Christ". Sacred Windows. Retrieved 2024-06-14.

- ^ Brock 1999a, p. 105.

- ^ Griffith 2002, p. 15, 20.

- ^ Palmer 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Griffith 2006, p. 447.

- ^ Debié 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Messo 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Simmons 1959, p. 13.

- ^ Toepel 2013, p. 540-584.

- ^ Wood 2007, p. 131-140.

- ^ Rubin 1998, p. 322-323.

- ^ Toepel 2013, p. 531-539.

- ^ Minov 2013, p. 157-165.

- ^ Ruzer 2014, p. 196-197.

- ^ Brock 1992c, p. 226.

- ^ Rompay 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Butts 2011, p. 390-391.

- ^ Butts 2019, p. 222.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 64-65.

- ^ Brock 1999b, p. 14-15.

- ^ Azéma 1965, p. 190-191.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Amar 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Brock 1999b, p. 15.

- ^ Rompay 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Minov 2020, p. 304.

- ^ Wood 2012, p. 186.

- ^ Minov 2013, p. 160.

- ^ "Sergey Minov, Cult of Saints, E02531".

- ^ a b c Pattie 1990, p. 174.

- ^ a b Bates 2000, p. 184.

- ^ McVey 1989, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bates 2000, p. 189.

- ^ Griffith 1999, p. 97-114.

- ^ Mourachian 2007, p. 30-31.

- ^ a b Bates 2000, p. 190.

- ^ a b Bates 2000, p. 191.

- ^ Beck, E. "Die Mariologie der echten Schriften Ephräms," Oriens Christianus 40 (1956).pp. 22–39.

- ^ a b c Horn 2015, p. 156.

- ^ Horn 2015, p. 155.

- ^ a b Rouwhorst 2012, pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b c Rouwhorst 2012, p. 141.

- ^ Rouwhorst 2012, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Rouwhorst 2012, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b Ashbrook Harvey, Susan (June 28, 2018). "Revisiting the Daughters of the Covenant: Women's Choirs and Sacred Song in Ancient Syriac Christianity". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 8 (2).

- ^ a b Ashbrook Harvey, Susan (2010). "Singing women's stories in Syriac tradition". Internationale kirchliche Zeitschrift. 100 (3): 171–183.

- ^ Mitchell 1912.

- ^ Mitchell, Bevan & Burkitt 1921.

- ^ Buck 1999, p. 77–109.

- ^ Toepel 2013, pp. 531–584.

- ^ a b c Pattie 1990, p. 175.

- ^ Brock & Harvey 1998.

- ^ Hostetler, Bob (2023-01-25). "Pray the Lenten Prayer of St. Ephrem". Guideposts. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ Passage, The Inside (2020-02-14). "Meditating on the prayer of St. Ephrem the Syrian during Lent". The Inside Passage. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ A list of works with links to the Greek text can be found online here.

- ^ "Venerable Ephraim the Syrian". www.oca.org. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "ЕФРЕМ СИРИН". www.pravenc.ru. Retrieved 2022-08-17.

- ^ PRINCIPI APOSTOLORUM PETRO at Vatican.va

- ^ New Advent at newadvent.org

- ^ "Ephrem". santosepulcro.co.il. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing. 2018. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

Sources

- Amar, Joseph Phillip (1995). "A Metrical Homily on Holy Mar Ephrem by Mar Jacob of Sarug: Critical Edition of the Syriac Text, Translation and Introduction". Patrologia Orientalis. 47 (1): 1–76.

- Azéma, Yvan, ed. (1965). Théodoret de Cyr: Correspondance. Vol. 3. Paris: Editions du Cerf.

- Bates, J. Barrington (June 2000). "Songs and Prayers Like Incense: The Hymns of Ephrem the Syrian". Anglican and Episcopal History. 69 (2): 170–192. JSTOR 42612097.

- Biesen, Kees den (2006). Simple and bold : Ephrem's art of symbolic thought (1st ed.). Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-397-8.

- Bou Mansour, Tanios (1988). La pensée symbolique de saint Ephrem le Syrien. Kaslik, Lebanon: Bibliothèque de l'Université Saint Esprit XVI.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1989). "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic Literature". ARAM Periodical. 1 (1): 11–23.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992a) [1985]. The Luminous Eye: The Spiritual World Vision of Saint Ephrem (2nd revised ed.). Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879075248.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992b). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum. ISBN 9780860783053.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992c). "Eusebius and Syriac Christianity". Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 212–234. ISBN 0814323618.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). "The Transmission of Ephrem's madrashe in the Syriac Liturgical Tradition". Studia Patristica. 33: 490–505. ISBN 9789068318685.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1999a). From Ephrem to Romanos: Interactions Between Syriac and Greek in Late Antiquity. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780860788003.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1999b). "St. Ephrem in the Eyes of Later Syriac Liturgical Tradition" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 2 (1): 5–25. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-020103. S2CID 212688898.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2000). "Greek Words in Ephrem and Narsai: A Comparative Sampling". ARAM Periodical. 12 (1–2): 439–449. doi:10.2143/ARAM.12.0.504480.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2003). "The Changing Faces of St Ephrem as Read in the West". Abba: The Tradition of Orthodoxy in the West. Crestwood: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 65–80. ISBN 9780881412482.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2004). "Ephrem and the Syriac Tradition". The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 362–372. ISBN 9780521460835.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2017). "The Armenian Translation of the Syriac Life of St Ephrem and Its Syriac Source". Reflections on Armenia and the Christian Orient. Yerevan: Ankyunacar. pp. 119–130. ISBN 9789939850306.

- Brock, Sebastian P.; Harvey, Susan A. (1998) [1987]. Holy Women of the Syrian Orient. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520213661.

- Buck, Christopher G. (1999). Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Baha'i Faith (PDF). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2011). "Syriac Language". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 390–391.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2019). "The Classical Syriac Language". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 222–242.

- Debié, Muriel (2009). "Syriac Historiography and Identity Formation". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1–3): 93–114. doi:10.1163/187124109X408014.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1986). "Ephraem, the Deacon of Edessa, and the Church of the Empire". Diakonia: Studies in Honor of Robert T. Meyer. Washington: CUA Press. pp. 25–52. ISBN 9780813205960.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1987). "Ephraem the Syrian's Hymns Against Julian: Meditations on History and Imperial Power". Vigiliae Christianae. 41 (3): 238–266. doi:10.2307/1583993. JSTOR 1583993.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1990). "Images of Ephraem: The Syrian Holy Man and His Church". Traditio. 45: 7–33. doi:10.1017/S0362152900012666. JSTOR 27831238. S2CID 151782759.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1997). Faith Adoring the Mystery: Reading the Bible with St. Ephraem the Syrian. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press. ISBN 9780874625776.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1998). "A Spiritual Father for the Whole Church: The Universal Appeal of St. Ephraem the Syrian" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 1 (2): 197–220. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-010113. S2CID 212688360.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (1999). "Setting Right the Church of Syria: Saint Ephraem's Hymns against Heresies". The Limits of Ancient Christianity: Essays on Late Antique Thought and Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 97–114. ISBN 0472109979.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2002). "Christianity in Edessa and the Syriac-Speaking World: Mani, Bar Daysan, and Ephraem, the Struggle for Allegiance on the Aramean Frontier". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 2: 5–20. doi:10.31826/jcsss-2009-020104. S2CID 166480216. Archived from the original on 2018-12-11. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2006). "St. Ephraem, Bar Daysān and the Clash of Madrāshê in Aram: Readings in St. Ephraem's Hymni contra Haereses". The Harp: A Review of Syriac and Oriental Studies. 21: 447–472. doi:10.31826/9781463233105-026.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2020). "Denominationalism in Fourth-Century Syria: Readings in Saint Ephraem's Hymns against Heresies, Madrāshê 22–24". The Garb of Being: Embodiment and the Pursuit of Holiness in Late Ancient Christianity. New York: Fordham University Press. pp. 79–100. ISBN 9780823287024.

- Hansbury, Mary (trans.) (2006). Hymns of St. Ephrem the Syrian (1. ed.). Oxford: SLG Press.

- Healey, John F. (2007). "The Edessan Milieu and the Birth of Syriac" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 10 (2): 115–127.

- Horn, Cornelia (2015). "Ancient Syriac Sources on Mary's Role as Intercessor". Presbeia Theothokou: The Intercessory Role of Mary across Times and Places in Byzantium (4th-9th Century) (1 ed.). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-7602-2. JSTOR j.ctv8pzdqp.13. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- Karim, Cyril Aphrem (2004). Symbols of the Cross in the Writings of the Early Syriac Fathers. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781593332303.

- Koonammakkal, Thomas (1991). The Theology of Divine Names in the Genuine Works of Ephrem. University of Oxford. ASIN B001OIJ75Q.

- Lipiński, Edward (2000). The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908598.

- McVey, Kathleen E., ed. (1989). Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809130931.

- Messo, Johny (2011). "The Origin of the Terms Syria(n) and Suryoyo: Once Again". Parole de l'Orient. 36: 111–125.

- Millar, Fergus (2011). "Greek and Syriac in Edessa: From Ephrem to Rabbula (CE 363-435)". Semitica et Classica. 4: 99–114. doi:10.1484/J.SEC.1.102508.

- Minov, Sergey (2013). "The Cave of Treasures and the Formation of Syriac Christian Identity in Late Antique Mesopotamia: Between Tradition and Innovation". Between Personal and Institutional Religion: Self, Doctrine, and Practice in Late Antique Eastern Christianity. Brepols: Turnhout. pp. 155–194.

- Minov, Sergey (2020). Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004445512.

- Mourachian, Mark (2007). "Hymns Against Heresies: Comments on St. Ephrem the Syrian". Sophia. 37 (2).

- Mitchell, Charles W., ed. (1912). S. Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Vol. 1. London: Text and Translation Society.

- Mitchell, Charles W.; Bevan, Anthony A.; Burkitt, Francis C., eds. (1921). S. Ephraim's Prose Refutations of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Vol. 2. London: Text and Translation Society.

- Palmer, Andrew N. (2003). "Paradise Restored". Oriens Christianus. 87: 1–46.

- Parry, Ken, ed. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9781405166584. ISBN 9781405166584.

- Pattie, T. S. (1990). "Ephraem's 'On Repentance' and the Translation of the Greek Text into Other Languages". The British Library Journal. 16 (2). British Library: 174–186. ISSN 0305-5167. JSTOR 42554306. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- Possekel, Ute (1999). Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042907591.

- Rompay, Lucas van (2000). "Past and Present Perceptions of Syriac Literary Tradition" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 3 (1): 71–103. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-030105. S2CID 212688244.

- Rompay, Lucas van (2004). "Mallpânâ dilan Suryâyâ Ephrem in the Works of Philoxenus of Mabbog: Respect and Distance" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 7 (1): 83–105. doi:10.31826/hug-2011-070107. S2CID 212688667.

- Rouwhorst, Gerard (2012). "Le Noyau le Plus Ancien des Hymnes de la Collection 'Sur L'Epiphanie' et la Question de Leur Authenticité". Vigiliae Christianae. 66 (2). BRILL: 139–159. ISSN 0042-6032. JSTOR 41480525. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- Rubin, Milka (1998). "The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language: A Case of Cultural Polemics in Antiquity". Journal of Jewish Studies. 49 (2): 306–333. doi:10.18647/2120/JJS-1998.

- Russell, Paul S. (2005). "Nisibis as the Background to the Life of Ephrem the Syrian" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 8 (2): 179–235. doi:10.31826/hug-2011-080113. S2CID 212688633.

- Ruzer, Serge (2014). "Hebrew versus Aramaic as Jesus' Language: Notes on Early Opinions by Syriac Authors". The Language Environment of First Century Judaea. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 182–205. ISBN 9789004264410.

- Simmons, Ernest (1959). The Fathers and Doctors of the Church. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company.

- Toepel, Alexander (2013). "The Cave of Treasures: A new Translation and Introduction". Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 531–584. ISBN 9780802827395.

- Wickes, Jeffrey (2015). "Mapping the Literary Landscape of Ephrem's Theology of Divine Names". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 69: 1–14. JSTOR 26497707.

- Wood, Philip (2007). Panicker, Geevarghese; Thekeparampil, Rev. Jacob; Kalakudi, Abraham (eds.). "Syrian Identity in the Cave of Treasures". The Harp. 22: 131–140. doi:10.31826/9781463233112-010. ISBN 9781463233112.

- Wood, Philip (2012). "Syriac and the Syrians". The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 170–194. ISBN 9780190277536.

External links

Media related to Ephrem the Syrian at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ephrem the Syrian at Wikimedia Commons

- Margonitho: Mor Ephrem the Syrian

- Anastasis article

- Hugoye: Influence of Saint Ephraim the Syrian, part 1

- Hugoye: Influence of Saint Ephraim the Syrian, part 2

- "St. Ephraem 'Faith Adoring the Mystery'". Archived from the original on 2008-06-13.

- Benedict XVI on St. Ephrem and his role in history

- Lewis E 235b Grammatical treatise (Ad correctionem eorum qui virtuose vivunt) at OPenn