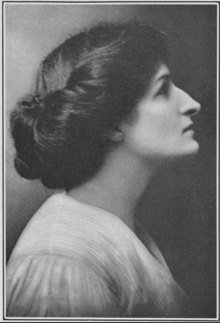

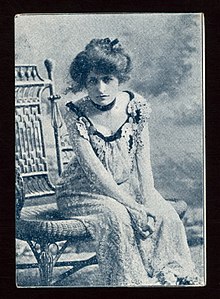

Edith Ellis (playwright)

Edith Ellis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 1866 Coldwater, Branch County, Michigan, US |

| Died | December 27, 1960 (aged 94) |

| Occupation | Dramatist |

| Children | Ellis Baker |

Edith Ellis (June 1866 – December 27, 1960) (also known as Edith Ellis Baker) was an American actress, director, and playwright.[1] She began her career as a child actress, and then began writing, directing, and producing. Ellis operated several theatres and touring companies throughout her lifetime. She is the author of over thirty-five plays. While not an outspoken feminist, Ellis’s work continuously focused on the issues of women. She also developed her own theory on directing, with a focus on the agency of the actor. Numerous times throughout her life, Ellis produced and directed her own writing.

Biography

Ellis was born in Coldwater, Branch County, Michigan.[2] She was the older sister of actor Edward Ellis. Her father, Edward C. Ellis, was a Shakespearean actor who began her career by putting her behind the curtain and on the stage from a very early age.[3] Her first part was at age six, and by ten she was a star. Three plays were written for her before her twelfth birthday. At fourteen, Ellis fell ill. During this time, she turned her attention to writing plays rather than acting.[3] She married Frank Baker, a theatre manager, in about 1895.[4] They were married until his death in 1907. Their daughter, Ellis Baker, became an actress. Edith later married C. Becher Furness, a Canadian, in 1909.

Career

Director

Ellis began her work as a director with the help of her husband, theatre manager Frank Baker. Ellis and husband secured and managed the Park Theatre in Brooklyn from 1901 to 1902. Ellis was the primary stage director there and her husband managed the administrative end until the theatre burned down at the end of the 1902 season.

Ellis and Baker then leased the Criterion Theatre, also in Brooklyn, where Ellis continued to direct plays. While there, Ellis formed the Baker Stock Company.[3] According to Ellis, this is when she did the "hardest work of [her] life, playing the leading roles in a new play every week, directing rehearsals, rewriting plays, planning scenery and properties and fairly living in the theatre.”[5] They later moved to the Berkeley Lyceum in New York City where she directed her own play, The Point of View.

In 1907, Frank Baker died. After his death, Ellis took back her maiden name and resumed directing, acting, and writing. Several times Ellis was head of her own stock companies, travelling or stationary, and wrote, produced, directed, and acted in many plays.

In 1908, Ellis acquired the New York Playhouse in Brooklyn. In 1909, Edith Ellis joined the Society of Dramatic Authors, a feminist group for women dramatics. Including members like Rachel Crothers, this group was a way for Ellis to network with other women in the industry.

Playwright

Her first writing attempt was out of necessity, when she and her brother, Edward, were stranded on the road by the unexpected disbanding of their theatrical company. The play was successful enough to pay their way home.

Ellis' plots typically followed one of three trajectories.[according to whom?] All three centered around women's issues.

- The unhappy life of a married woman (Mary Jane's Pa, 1910)

- Women in the workforce (The Point of View, 1903)

- Women above the age of forty (The White Villa, 1921)

Ellis had difficulty in getting some of her plays produced, as in the case of The White Villa. The White Villa is a play about a woman in an unfulfilled marriage who decides to leave her husband. The play ends with the leading woman now living her life alone while her ex-husband has remarried a younger woman.

One male producer liked The White Villa but wouldn’t produce it. Another male reader (who was married to an actress) said that he enjoyed reading the play, but would never let his wife star in it. A third producer claimed that he would produce the play, except that women in the audience would hate the play’s truthful narrative, saying “Women won’t stand for the truth.”[6] Edith Ellis eventually produced the play herself and would self-produce a majority of her works.

In 1936, Ellis began transcribing works about life after death. She said this idea came from a New England farm boy who was killed by a British soldier in 1781. These works include: Incarnation: A Plea from the Masters, (1936), Open the Door!, (1935), We Knew These Men, (1943) and Love in the Afterlife, (1956)

She also wrote silent film scenarios for Samuel Goldwyn.

Feminism in theatre

In 1909, Ellis joined the Society of Dramatic Authors, a feminist group for women dramatics. Including members like Rachel Crothers, this group was a way for Ellis to network with other women in the industry.

Although Ellis rejected the suffragette title, she was the most vocal directress at the time when it came to her political beliefs concerning women. Ellis’s commercial success as a playwright and director meant that she could present productions with feminist narratives. Having never categorized her work as feminist, she was able to present plays that disrupted expectations of gender roles, particularly the notion that women were passively happy in the domestic sphere.

Additionally, most of the plays that Ellis directed were not written by her, but written by other women. Edith Ellis produced women’s plays almost exclusively.[3]

Directing theory

Ellis developed a feminist directing theory. In her words: “My methods differ somewhat from those of the men directors. The men like first to put the company through the rough outline of the play, the mechanics as we say, leaving the characterizations to be developed later along with details and business. I prefer to stay ‘living’ the play from the first and working out the detail as we go slowly along. In this way the sense of reality is created, and the play is already properly colored.” [3]

According to Ellis, women biologically made better directors because women had an ability to impart their knowledge to the cast, whereas male directors did not have the inborn emotional inclination or intuition of women. The only advantage that men had as directors, according to Ellis, was their ability to obtain directing positions. To some scholars, this part of her theory is problematic because Ellis attributes differences in gender to biological causes.[3]

A major element of Ellis’ directing theory was maintaining an actor’s agency regarding character interpretations. According to Ellis, it was crucial that directors not eliminate the intelligence of the actor. As a former actress, Ellis was very familiar with the lowly treatment of actors by their directors. Actresses (female actors) were treated especially poorly by directors, so Ellis made a point to grant actresses agency in her rehearsal and performance space.[3]

Works

- A Batch of Blunders, 1897

- Mrs. B. O'Shaughnessy (Wash Lady), 1900

- Because I Love You, 1903

- The Point of View, 1904

- Mary and John, 1905

- The Wrong Man, 1905

- Contrary Mary, 1905

- Ben of Broken Bow, 1905

- The Swallow, 1906

- Mary Jane's Pa, 1906

- My Man (with F. Halsey), 1910

- He Fell In Love With His Wife, 1910

- Seven Sisters, 1912

- Partners, 1912

- The Love Wager, 1912

- Verspers, 1912

- Fields of Flax, 1912

- The Man Higher Up, 1912

- The Amethyst Ring, 1913

- Cupid's Ladder, 1915

- Make Believe, 1915

- Man with the Black Gloves, 1915,

- The Devil's Garden, 1915

- Making Dick Over, 1916

- Mrs. Clancey's Car Ride, with Edward Ells, 1918

- Whose Little Bride Are You, 1919

- Bravo, Claudia, 1919

- Mrs. Jimmie Thompson (with Norman S. Rose), 1920

- The White Villa, 1921

- Betty's Last Bet, 1921

- The Judsons Entertain, 1922

- The Illustrious Tartarin, 1922

- White Collars, 1924

- The Moon and Sixpence, 1924

- The Last Chapter (with Edward Ellis), 1930

- The Lady of La Paz, 1926

References

- ^ Edith Ellis, United States census, 1870; Matteson, Branch, Michigan; roll M593_665, page 232A, line 26, Family History film 552164. Retrieved on 2019-08-10.

- ^ "Obituaries". The Norwalk Hour. December 28, 1960.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cobrin, Pamela (2009). From Winning the Vote to Directing on Broadway:The Emergence of Women on the New York Stage, 1880-1927. Newark: University of Delaware Press. pp. 194–199, 203. ISBN 978-0-87413-058-4.

- ^ Edith Baker, United States census, 1900; Chicago Ward 34, Cook, Illinois; page 10,, enumeration district 1084, Family History film 1240289. Retrieved on 2019-08-10.

- ^ "Edith Ellis Baker's Thanks". Brooklyn Eagle. February 1, 1909.

- ^ Patterson, Ada (March 20, 1920). "Let Edith Ellis Tell It". The Morning Telegraph.

Further reading

- Patterson, Ada (May 1909). "A Woman Insurgent Dramatist". The Theatre. New York: 152–154.

External links

Media related to Edith Ellis (playwright) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edith Ellis (playwright) at Wikimedia Commons- Edith Ellis at the Internet Broadway Database

- Edith Ellis at IMDb