Electron nuclear double resonance

Electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) is a magnetic resonance technique for elucidating the molecular and electronic structure of paramagnetic species.[1] The technique was first introduced to resolve interactions in electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra.[2][3] It is currently practiced in a variety of modalities, mainly in the areas of biophysics and heterogeneous catalysis.

CW experiment

In the standard continuous wave (cwENDOR) experiment, a sample is placed in a magnetic field and irradiated sequentially with a microwave followed by radio frequency. The changes are then detected by monitoring variations in the polarization of the saturated electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) transition.[4]

Theory

ENDOR is illustrated by a two spin system involving one electron (S=1/2) and one proton (I=1/2) interacting with an applied magnetic field.

The Hamiltonian for the system

The Hamiltonian for the two-spin system mentioned above can be described as

The four terms in this equation describe the electron Zeeman interaction (EZ), the nuclear Zeeman interaction (NZ), the hyperfine interaction (HFS), and the nuclear quadrupole interaction (Q), respectively.[4]

The electron Zeeman interaction describes the interaction between an electron spin and the applied magnetic field. The nuclear Zeeman interaction is the interaction of the magnetic moment of the proton with an applied magnetic field. The hyperfine interaction is the coupling between the electron spin and the proton's nuclear spin. The nuclear quadrupole interaction is present only in nuclei with I>1/2.

ENDOR spectra contain information on the type of nuclei in the vicinity of the unpaired electron (NZ and EZ), on the distances between nuclei and on the spin density distribution (HFS) and on the electric field gradient at the nuclei (Q).

Principle of the ENDOR method

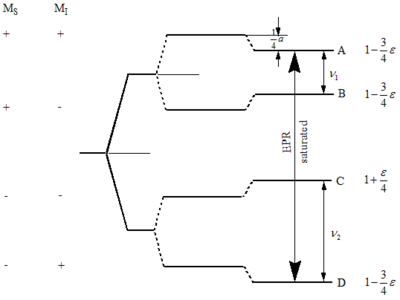

The right figure illustrates the energy diagram of the simplest spin system where a is the isotropic hyperfine coupling constant in hertz (Hz). This diagram indicates the electron Zeeman, nuclear Zeeman and hyperfine splittings. In a steady state ENDOR experiment, an EPR transition (A, D), called the observer, is partly saturated by microwave radiation of amplitude while a driving radio frequency (rf) field of amplitude , called the pump, induces nuclear transitions.[5] Transitions happen at frequencies and and obey the NMR selection rules and . It is these NMR transitions that are detected by ENDOR via the intensity changes to the simultaneously irradiated EPR transition. Both the hyperfine coupling constant (a) and the nuclear Larmor frequencies () are determined when using the ENDOR method.[6]

Requirement for ENDOR

One requirement for ENDOR is the partial saturation of both the EPR and the NMR transitions defined by

and

where and are the gyromagnetic ratio of the electron and the nucleus respectively. is the magnetic field of the observer which is microwave radiation while is the magnetic field of the pump which is radio frequency radiation. and are the spin-lattice relaxation time for the electron and the nucleus respectively. and are the spin-spin relaxation time for the electron and the nucleus respectively.

ENDOR spectroscopy

EI-EPR

ENDOR-induced EPR (EI-EPR) displays ENDOR transitions as a function of the magnetic field. While the magnetic field is swept through the EPR spectrum, the frequency follows the Zeeman frequency of the nucleus. The EI-EPR spectra can be collected in two ways: (1) difference spectra[7] (2) frequency modulated rf field without Zeeman modulation.

This technique was established by Hyde[7] and is especially useful for separating overlapping EPR signals which result from different radicals, molecular conformations or magnetic sites. EI-EPR spectra monitor changes in the amplitude of an ENDOR line of the paramagnetic sample, displayed as a function of the magnetic field. Because of this, the spectra corresponds to one species only.[5]

Double ENDOR

Double electron-nuclear-double resonance (Double ENDOR) requires the application of two rf (RF1 and RF2) fields to the sample. The change in signal intensity of RF1 is observed while RF2 is swept through the spectrum.[5] The two fields are perpendicularly oriented and are controlled by two tunable resonance circuits which can be adjusted independent of each other.[8] In spin decoupling experiments,[9] the amplitude of the decoupling field should be as large as possible. However, in multiple quantum transition studies, both rf fields should be maximized.

This technique was first introduced by Cook and Whiffen[10] and was designed so that the relative signs of hf coupling constants in crystals as well as separating overlapping signals could be determined.

CP-ENDOR and PM-ENDOR

The CP-ENDOR technique makes use of circularly polarized rf fields. Two linearly polarized fields are generated by rf currents in two wires which are oriented parallel to the magnetic field. The wires are then connected into half loops which then cross at a 90 degree angle. This technique was developed by Schweiger and Gunthard so that the density of ENDOR lines in a paramagnetic spectrum could be simplified.[11]

Polarization modulated ENDOR (PM-ENDOR) uses two perpendicular rf fields with similar phase control units to CP-ENDOR. However, a linearly polarized rf field which rotates in the xy-plane at a frequency less than the modulation frequency of the rf carrier is used.[5]

Applications

In polycrystalline media or frozen solution, ENDOR can provide spatial relationships between the coupled nuclei and electron spins. This is possible in solid phases where the EPR spectrum arises from the observance of all orientations of paramagnetic species; as such the EPR spectrum is dominated by large anisotropic interactions. This is not so in liquid phase samples where spatial relationships are not possible. Such spatial arrangements require that the ENDOR spectra are recorded at different magnetic field settings within the EPR powder pattern.[12]

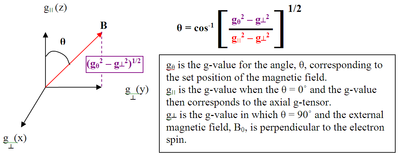

The traditional convention of magnetic resonance envisions the paramagnets aligning with the external magnetic field; however, in practice it is simpler to treat the paramagnets as fixed and the external magnetic field as a vector. Specifying positional relationships requires three separate but related pieces of information: an origin, the distance from said origin, and a direction of that distance.[13] The origin, for purposes of this explanation, can be thought of as the position of a molecule's localized unpaired electron. To determine the direction to the spin active nucleus from the localized unpaired electron (remember: unpaired electrons are, themselves, spin active) one employs the principle of magnetic angle selection. The exact value of θ is calculated as follows to the right:

At θ = 0˚ the ENDOR spectra contain only the component of hyperfine coupling that is parallel to the axial protons and perpendicular to the equatorial protons. At θ = 90˚ ENDOR spectra contain only the component of hyperfine coupling that is perpendicular to the axial protons and parallel to the equatorial protons. The electron nuclear distance (R), in meters, along the direction of the interaction is determined by point-dipole approximation. Such approximation takes into account the through-space magnetic interactions of the two magnetic dipoles. Isolation of R gives the distance from the origin (localized unpaired electron) to the spin active nucleus. Point-dipole approximations are calculated using the following equation on the right:

ENDOR technique has been used to characterize of spatial and electronic structure of metal-containing sites. paramagnetic metal ions/complexes introduced for catalysis; metal clusters producing magnetic materials; trapped radicals introduced as probes for disclosing the surface acid/base properties; color centers and defects as in ultramarine blue and other gems; and catalytically formed trapped reaction intermediates that detail the mechanism. The application of pulsed ENDOR to solid samples provides for many advantages compared to CW ENDOR. Such advantages are the generation of distortion-less line shapes, manipulation of spins through a variety of pulse sequences, and the lack of dependence on a sensitive balance between electron and nuclear spin relaxation rates and applied power (given long enough relaxation rates).[12]

HF pulsed ENDOR is generally applied to biological and related model systems. Applications have been primarily to biology with a heavy focus on photosynthesis related radicals or paramagnetic metal ions centers in matalloenzymes or metalloproteins.[14] Additional applications have been to magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. HF ENDOR has been used as a characterization tool for porous materials, for the electronic properties of donors/acceptors in semiconductors, and for electronic properties of endohedral fullerenes. Framework Substitution with W-band ENDOR has been used to provide experimental evidence that a metal ion is located in the tetrahedral framework and not in a cation exchange position. Incorporation of transition metal complexes into the framework of molecular sieves is of consequence as it could lead to the development of new materials with catalytic properties. ENDOR as applied to trapped radicals has been used to study NO with metal ions in coordination chemistry, catalysis and biochemistry.[12]

See also

References

- ^ Kevan, L and Kispert, L. D. Electron Spin Double Resonance Spectroscopy Interscience: New York, 1976.

- ^ Feher, G (1956). "Observation of Nuclear Magnetic Resonances via the Electron Spin Resonance Line". Phys. Rev. 103 (3): 834–835. Bibcode:1956PhRv..103..834F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.103.834./

- ^ Kurreck, H.; Kirste, B.; Lubitz, W. Electron Nuclear Double Resonance Spectroscopy of Radicals in Solution VCH Publishers: New York, 1988.

- ^ a b Gemperle, C; Schweiger, A (1991). "Pulsed Electron-Nuclear Double Resonance Methodology". Chem. Rev. 91 (7): 1481–1505. doi:10.1021/cr00007a011./

- ^ a b c d e Schweiger, A. Structure and Bonding: Electron Nuclear Double Resonance of Transition Metal Complexes with Organic Ligands Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1982.

- ^ Murphy, D. M.; Farley, R. D. (2006). "Principles and applications of ENDOR spectroscopy for structure determination in solution and disordered matrices". Chem. Soc. Rev. 35 (3): 249–268. doi:10.1039/b500509b. PMID 16505919./

- ^ a b Hyde, J. S. (1965). "ENDOR of Free Radicals in Solution". J. Chem. Phys. 43 (5): 1806–1818. Bibcode:1965JChPh..43.1806H. doi:10.1063/1.1697013./

- ^ Forrer, J.; Schweiger, A.; Gunthard, H. (1977). "Electron-nuclear-nuclear triple-resonance spectrometer". J. Phys. E: Sci. Instrum. 10 (5): 470–473. Bibcode:1977JPhE...10..470F. doi:10.1088/0022-3735/10/5/015.

- ^ Schweiger, A.; Rudin, M.; Gunthard H. (1980). "Nuclear spin decoupling in ENDOR spectroscopy". Mol. Phys. 41 (1): 63–74. Bibcode:1980MolPh..41...63S. doi:10.1080/00268978000102571./

- ^ Cook, R. J.; Whiffen, D.H. (1964). "Relative signs of hyperfine coupling constants by a double ENDOR experiment". Proc. Phys. Soc. 84 (6): 845–848. Bibcode:1964PPS....84..845C. doi:10.1088/0370-1328/84/6/302./

- ^ Schweiger, A.; Gunthard, H. (1981). "Electron nuclear double resonance with circularly polarized radio frequency fields (CP-ENDOR) theory and applications". J. Mol. Phys. 42 (2): 283–295. Bibcode:1981MolPh..42..283S. doi:10.1080/00268978100100251./

- ^ a b c Goldfarb, D. (2006). "High field ENDOR as a characterisation tool for functional sites in microporous materials". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8 (20): 2325–2343. Bibcode:2006PCCP....8.2325G. doi:10.1039/b601513c. PMID 16710481./

- ^ Murphy, D. M.; Farley, R. D. (2006). "Principles and applications of ENDOR spectroscopy for structure determination in solution and disordered matrices". Chem. Soc. Rev. 35 (23): 249–268. doi:10.1002/chin.200623300. PMID 16505919./

- ^ Telser, J. "ENDOR spectroscopy" in Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: New York, 2011. [1]