Dual Contracts

The Dual Contracts, also known as the Dual Subway System, were contracts for the construction and/or rehabilitation and operation of rapid transit lines in the City of New York. The contracts were signed on March 19, 1913, by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. As part of the Dual Contracts, the IRT and BRT would build or upgrade several subway lines in New York City, then operate them for 49 years.

Most of the lines of the present-day New York City Subway were built or reconstructed under these contracts. The contracts were "dual" in that they were signed between the City and two separate private companies. Both the IRT and BRT (later Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, or BMT) worked together to make the construction of the Dual Contracts possible.

Background

In the late 19th century and for most of the 20th century, New York was host to millions of immigrants each year. Many of the immigrants crowded into tenements and other apartment buildings in the inner city. This resulted in overpopulation of the buildings, and congestion of city streets. Manhattan's population had risen from 516,000 people in 1850 to 2.33 million people in 1910.[1] The population of the entire city had grown from 1.17 million people in 1860 to 3.44 million in 1900 and 4.77 million in 1910.[2] Living in Manhattan was becoming a hazard due to the higher probability of crime and overcrowding, and for the most part, the first subway line only served areas that were already developed.[3] The first subway lines to the outer boroughs were planned during the early 20th century.[4] Dispersion resulted in the expansion and development of the boroughs.

In 1906, Charles Evans Hughes was elected as the governor of New York, and the next year, he created the New York State Public Service Commission (PSC). The PSC was responsible for new rapid transit lines in New York City. Although the PSC had created ambitious plans for the expansion of the city's subway system, they only had $200 million on hand.[5] In 1911, George McAneny was appointed leader of the Transit Committee of the New York City Board of Estimate, which oversaw the subway expansion plans.[6]

Some opposed the Dual Contracts as they thought that the company owners and city officials were just looking for another way to produce personal revenue.[6] Reformists like Hughes and McAneny would not have it any other way than to see the expansion of the city and the subway. They wanted to see the inner city become less populated and spread the people to the outer boroughs of the city. They planned to expand the city and disperse the people by building subway lines which would hopefully result in new homes being built near the subway lines and the areas surrounding. This would lower population densities in the city and also made as a good reason to help prove the subway expansion as necessary.

Crowding

Before the Contracts, there was crowding in many of the forms of transportation in the city. The following is a list of annual ridership for each mode of transportation between June 30, 1910, and June 30, 1911:

- Interborough Rapid Transit Company–subways, elevated roads — 578,154,088

- Hudson and Manhattan Railroad — 52,756,434

- Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad System — 167,371,328

- East River ferries — 23,460,000

- Municipal ferry to Staten Island — 10,540,000

- Hudson River ferries — 91,776,200

In total, 924,058,050 passengers were carried that year over these six modes of transport.[7]

The New York Times noted that streetcar ridership had increased more than 25 times over between 1860, where there were 50.83 million annual riders, and 1910, where there were 1.531 billion annual riders.[2]

Planned effects

It was expected that, within five years of completion:

When completed, the rapid transit facilities of the City will have been more than trebled. During the year ended June 30, 1911, shortly after which the construction of the new system was begun, the existing rapid transit lines carried 798,281,850 passengers. The new Dual System will have a capacity of upwards of [3 billion], although it is not expected that such capacity will be demanded immediately upon the completion of the system. The combined trackage of the existing lines (including 7.1 miles of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad) amounts to 303 miles of single track. To this will be added by the new lines of the Dual System 334 miles of single track, making a new system with 637 miles of single track. What this will mean to the City may be appreciated by considering how the existing lines will be amplified by the new additions and extensions. The Hudson and Manhattan road, however, is not to be a part of the Dual System.[7]

This system expansion was expected to be as big as, if not bigger, than the proposed Second System expansion put forth by the Independent Subway System in 1929 and 1939.

Contracts

Contracts 1 and 2

Built before the Dual Contracts, the first regularly operated subway in New York City was built by the city and leased to the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) for operation under city Contracts 1 and 2. Until 1918, when the new "H" system that is still operated – with separate East Side and West Side lines – was placed in service, it consisted of a single trunk line below 96th Street with several northern branches. The system had four tracks between Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall and 96th Street, allowing for local and express service on that portion.

Contract 1 was for the original 28 stations of the subway system that opened on October 27, 1904, from City Hall to 145th Street, as well as for stations opened before 1908 on several IRT extensions. The original system as included in Contract 1 was completed on January 14, 1907, when trains started running across the Harlem Ship Canal on the Broadway Bridge to 225th Street,[8] and the Contract 2 portion was opened to Atlantic Avenue on May 1, 1908.[9]

Contracts 3 and 4

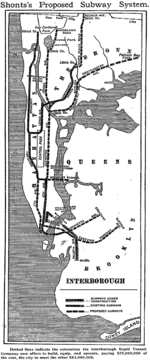

The Dual Contracts were signed on March 19, 1913. The contracts bound Interborough Rapid Transit Company and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT; later BMT) to build and operate lines for 49 years.[10] Contract 3 was signed between the City and the IRT. Contract 4 was signed between the City and the Municipal Railway Company, a subsidiary of the BRT, formed especially for the purpose of contracting with the city for construction of the lines.

Under the terms of Contracts 3 and 4, the city would build new subway and elevated lines, and rehabilitate and expand certain existing elevated lines, and lease them to the private companies for operation. The expansions would total 618 miles (995 km) of new trackage across both systems; by comparison, the existing systems had 296 miles (476 km) of tracks. The city's third major rapid transit company, the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (now PATH), was excluded from the contracts.[2] The projected $337 million cost would be borne mostly by the City, which was to pay $226 million, and the companies would pay the difference.[11][2] The City's contribution was in cash raised by bond offerings, while the companies' contributions were variously by supplying cash, facilities and equipment to run the lines.

Queensboro Plaza

The contract negotiations were long and sometimes acrimonious. For instance, when the IRT was reluctant to cede the BRT's proposed access to Midtown Manhattan via the Broadway Line, the city and state negotiators immediately offered the BRT all of the lines under proposal. This included lines that would have only been operable using IRT rolling stock dimensions, such as the upper Lexington Avenue Line and both lines in Queens. The IRT quickly gave in to the "invasion" of Midtown Manhattan by the BRT.[12][13]

The assignment of the proposed lines in Queens proved to be an imposition on both companies. Instead of one company enjoying a monopoly in that borough, both proposed lines—a short line to Astoria, and a longer line reaching initially to Corona, and eventually to Flushing—were assigned to both companies, to be operated in what was called "joint service". The lines would start from a large interchange station, Queensboro Plaza. The IRT would access the station from both the 1907 Steinway Tunnel and an extension of the Second Avenue Elevated from Manhattan over the Queensboro Bridge. The BRT would feed the Queens lines from the 60th Street Tunnel in Manhattan. Technically the line was under IRT "ownership", but the BRT/BMT was granted trackage rights in perpetuity, essentially making it theirs also.[12][13]

The BRT had a big disadvantage, as both Queens lines were built to IRT specifications. This meant that IRT passengers had a one-seat ride to Manhattan destinations, whereas BRT passengers had to make a change at Queensboro Plaza. This came to be important when service was extended for the 1939 World's Fair, as the IRT was able to offer direct express trains from Manhattan, and the BRT was not. This practice lasted well into the municipal ownership of the lines, and was not ended until 1949. Both companies shared in the revenues from this service. To facilitate this arrangement originally, extra long platforms were constructed along both Queens routes, so separate fare controls/boarding areas could be established. This quickly turned out to be operationally unworkable, so eventually a proportionate formula was worked out. The bonus legacy of this construction was that the IRT was able to operate 11-car trains on this line, and when the BMT took over the Astoria Line, minimal work had to be done to accommodate 10-car BMT units.[13]

Conditions

Several provisions were imposed on the companies, which eventually led to their downfall and consolidation into city ownership in 1940:

- The fare was limited to five cents; that led to financial troubles for the two companies after post-World War I inflation. The BMT could charge ten cents for fare to Coney Island Terminal, as well as to stations "where such ten cent fare is now allowed, until the time when trains may be operated for continuous trips over wholly connected portions of the railroad" between Coney Island and the Chambers Street station in Manhattan.[14]

- The City had the right to "recapture" any of the lines it built and run them as its own.[14]

- The City was to share in the profits.[14]

There were other conditions in regards to specific operations of the lines, as part of a deal between the IRT, the BMT, and the Public Service Commission. Many of the conditions applied all across the dual system. For example:

- After the Commission finished constructing the line, the company was to operate it, providing its own rolling stock and furnishings.[14]

- The companies, if they operated lines temporarily, had to operate them as if they were subway extensions. For subway extensions, if a company accepted the extension, it could operate it as part of its system; if not, the company had to pay a significant amount to the city every three months to operate it. This was implemented as part of the Queensboro Plaza trackage-sharing operation.[14]

- The companies had operated these lines "according to the highest standards of railway operation and with due regard to the safety of the passengers and employees thereof, and of all other persons."[14]

- Free transfers would be given at stations where needed, such as transfer stations between lines of the IRT and BMT, bus–subway transfer stations, elevated–subway transfer stations, or streetcar–subway transfer stations, according to the Commission's discretion.[14]

- Freight, mail and express trains could use these companies' tracks if they did not disrupt passenger operations.[14]

- Advertising was prohibited in stations, railroad tunnels, elevated structures, or other places. Bulletins telling of service changes were allowed.[14]

- Selling things in the stations was prohibited, except if it needed for the operation of the subway, or if it was a newspaper, periodical, or magazine that the Commission had permitted.[14]

- Each company was to post their intentions to operate newsstands in the form of proposals to the Commission.[14]

Some conditions applied only to certain parts of the system:

- The BMT agreed to hand out transfers at the 86th Street/Gravesend station in Brooklyn to the Third Avenue Line and the Fifth Avenue Line streetcar lines to 86th Street and Fort Hamilton Parkway. They were also to extend these streetcar lines to 86th Street and Fourth Avenue, where a transfer could be made at the 86th Street/Fourth Avenue station.[14]

- The BMT also agreed to make transfers with the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad from the 34th Street subway station to the 33rd Street H&M station. The transfers applied to passengers going to Grand Central Terminal,[14] since the H&M had originally planned an extension there.[15]

- The IRT agreed to equip and operate the Steinway Tunnel until it was rebuilt and completed. Then, the Steinway Tunnel was still a trolley tunnel with no subway connection. Transfers were to be made to IRT rapid transit lines at the Grand Central–42nd Street station. The Commission approved single-car rolling stock for the line.[14]

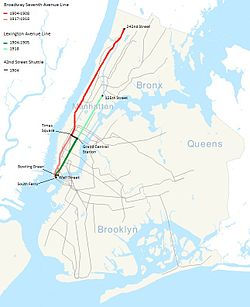

IRT lines

Under the original system, the original line and early extensions built for the IRT are:

- Eastern Parkway Line from Atlantic Avenue–Barclays Center to Borough Hall

- Lexington Avenue Line from Borough Hall to Grand Central–42nd Street

- 42nd Street Shuttle from Grand Central–42nd Street to Times Square

- Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line from Times Square to Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street

- Lenox Avenue Line from 96th Street to 145th Street

- White Plains Road Line from 142nd Street Junction to 180th Street–Bronx Park (removed north of 179th Street)

The following lines were built under the Dual Contracts for the IRT:[7]

- Astoria Line and Flushing Line

- Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line south of Times Square–42nd Street, including the Brooklyn Branch

- Lexington Avenue Line north of Grand Central–42nd Street

- Jerome Avenue Line

- Ninth Avenue Line from 155th Street to the Jerome Avenue Line

- Pelham Line

- White Plains Road Line north of 177th Street (present-day Tremont Avenue)

- Eastern Parkway Line beyond Atlantic Avenue

- Nostrand Avenue Line

- New Lots Line

The following lines were rebuilt with extra tracks:[7]

- Ninth Avenue Line from Rector Street to 155th Street (one new track)

- Second Avenue and Third Avenue Lines from City Hall station to 129th Street and from 116th Street to 155th Street, respectively.

Some of the IRT lines proposed under the Contracts were not built. Most notably, there were plans to build an IRT line to Marine Park, Brooklyn (at what is now Kings Plaza) under either Utica Avenue, using a brand-new line, or Nostrand Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, using the then-new IRT Nostrand Avenue Line. There were also alternate plans for the Nostrand Avenue Line to continue down Nostrand Avenue to Sheepshead Bay.[16]

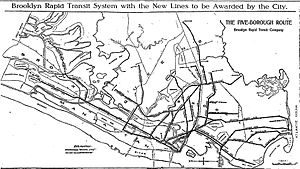

BMT lines

All Manhattan and Queens BMT lines were built under the Dual Contracts, as were all subway and some elevated lines in Brooklyn.[7]

Newly built lines and line segments

- 14th Street Eastern Line west of Broadway Junction; two-tracked underground structure

- Astoria Line and Flushing Line east of Queensboro Plaza (trackage rights over IRT); both three-track elevated structures

- Broadway Line; four-track underground structure

- Brighton Beach Line between DeKalb Avenue and Prospect Park

- Fourth Avenue Line; underground structure with four tracks north of 59th Street and two tracks south of 59th Street

- Fulton Street Line east of Grant Avenue; three-track elevated structure

- Jamaica Line east of Cypress Hills; two-track elevated structure

- Manhattan Bridge tracks and approaches

- Nassau Street Line between Chambers Street to a merge with the Montague Street Tunnel to Brooklyn

Grade-separated rights-of-way built to replace surface railroads

- Brighton Beach Line between Neptune Avenue (south of Sheepshead Bay) and Coney Island–Stillwell Avenue. Four-track elevated structure.

- Culver Line between Ninth Avenue and West Eighth Street (merge with Brighton Beach Line). Three-track elevated structure.

- Myrtle Avenue Line east of Myrtle–Wyckoff Avenues. Two-track elevated structure.

- Sea Beach Line from Fourth Avenue Subway to 86th Street. Four-track open cut.

- West End Line between Ninth Avenue and Bay 50th Street. Three-track elevated structure.

Existing rights-of-way rehabilitated and expanded

- Brighton Beach Line from Prospect Park to Church Avenue. Existing open cut widened and expanded from two to four tracks.

- Jamaica Line from merge with line from Marcy Avenue to Broadway Junction. Elevated line expanded from two to three tracks.

- Myrtle Avenue Line from Broadway–Myrtle to Myrtle–Wyckoff Avenues, including track connection to Jamaica Line. Elevated structure expanded from two to three tracks.

- Fulton Street Line from Nostrand Avenue to east of split from Canarsie Line at Pitkin Avenue. Two track elevated expanded to three tracks and new flying junction complex with six tracks replaced two tracks between former Manhattan Junction in East New York and Pitkin Avenue. This portion gave the Canarsie Line two dedicated tracks.

Effects

As reformists predicted, the Dual Contracts resulted in city expansion. People moved to the newly built homes along the newly built subway lines. These homes were affordable, about the same cost as the houses in Brooklyn and Manhattan.[11] The Dual Contracts were the key to dispersion of the city's congested areas. The Dual Contracts helped lower high population areas and probably helped save lives as people were no longer living in heavily diseased areas. According to the Federal Census of New York City for 1920 the population in Manhattan below 59th Street decreased from 1910 to 1920. The census resulted in the following:

- 1905 State census: 1,271,848

- 1910 United States census: 1,269,591

- 1915 State census: 1,085,308

- 1920 United States census: 1,059,589[17]

People were allowed to move to better parts the same cost and could have a better and more comfortable life in the suburbs. They could still commute to work every day as most of the better off city workers who moved to the outer boroughs did.[11] This also helped the business districts as people could still work.

References

Notes

- ^ Derrick 2001, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d "618 MILES OF TRACK IN THE DUAL SYSTEM; City Will Have Invested $226,000,000 When Rapid Transit Project Is Completed". The New York Times. August 3, 1913. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Derrick 2001, p. 2–3.

- ^ Derrick 2001, p. 265.

- ^ Derrick 2001, p. 4–5.

- ^ a b Derrick 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e "The Dual System of Rapid Transit (1912)". nycsubway.org.

- ^ The New York Times, Farthest North in Town by the Interborough, January 14, 1907, page 18

- ^ The New York Times, Brooklyn Joyful Over New Subway, May 2, 1908, page 1

- ^ "Subway Contracts Solemnly Signed; Cheers at the Ceremonial Function When McCall Gets Willcox to Attest" (PDF). The New York Times. March 20, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Derrick 2001, p. 7.

- ^ a b Public Service Commission 1913, chapter 1.

- ^ a b c Rogoff 1960.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Terms and Conditions of Dual System Contracts". nycsubway.org. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ "M'ADOO EXTENSION TO BE READY IN 1911; Head of Hudson & Manhattan Road Promises It After the Board of Estimate Approves. BUSINESS MEN GRATIFIED Mr. McAdoo Also Happy – He Will Begin at Once to Complete the Jersey-Grand Central Route". The New York Times. June 5, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "TRANSIT OUTLOOK BRIGHT IN BROOKLYN; First Branch Lines on Assessment Plan Likely to be Built in That Borough". The New York Times. March 6, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ "Lower Manhattan Lost in Population" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

Sources

- Derrick, Peter (2001). Tunneling to the Future: The Story of the Great Subway Expansion that Saved New York. NYU Press. ISBN 0814719104.

- New Subways For New York: The Dual System of Rapid Transit. Public Service Commission. 1913.

- Rogoff, David (1960). "The Steinway Tunnels". Electric Railroads (29).

External links

- nycsubway.org — The Dual Contracts

- Story including 50th anniversary of the contracts