Diogenes

Diogenes of Sinope | |

|---|---|

Statue of Diogenes in Sinop, Turkey | |

| Born | 412 or 404 BC

|

| Died | 323 BC (aged 81 or 89) |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Cynicism |

| Notable students | Crates of Thebes |

Notable ideas | Cosmopolitanism |

Diogenes (/daɪˈɒdʒɪniːz/ dy-OJ-in-eez; Ancient Greek: Διογένης, romanized: Diogénēs [di.oɡénɛːs]), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (Διογένης ὁ Κυνικός, Diogénēs ho Kynikós) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism. He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia, in 412 or 404 BC and died at Corinth in 323 BC.[1]

Diogenes was a controversial figure. He was banished, or he fled, from Sinope over debasement of currency. He was the son of the mintmaster of Sinope, and there is some debate as to whether it was he, his father, or both who had debased the Sinopian currency.[2] After his hasty departure from Sinope he moved to Athens where he proceeded to criticize many conventions of Athens of that day. There are many tales about him following Antisthenes and becoming his "faithful hound".[3] Diogenes was captured by pirates and sold into slavery, eventually settling in Corinth. There he passed his philosophy of Cynicism to Crates, who taught it to Zeno of Citium, who fashioned it into the school of Stoicism, one of the most enduring schools of Greek philosophy.

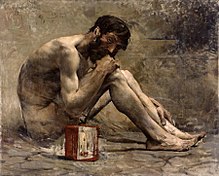

No authenticated writings of Diogenes survive, but there are some details of his life from anecdotes (chreia), especially from Diogenes Laërtius' book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers and some other sources.[4] Diogenes made a virtue of poverty. He begged for a living and often slept in a large ceramic jar, or pithos, in the marketplace.[5] He used his simple lifestyle and behavior to criticize the social values and institutions of what he saw as a corrupt, confused society. He had a reputation for sleeping and eating wherever he chose in a highly non-traditional fashion and took to toughening himself against nature. He declared himself a cosmopolitan and a citizen of the world rather than claiming allegiance to just one place.

He modeled himself on the example of Heracles, believing that virtue was better revealed in action than in theory. He became notorious for his philosophical stunts, such as carrying a lamp during the day, claiming to be looking for a "man" (often rendered in English as "looking for an honest man", as Diogenes viewed the people around him as dishonest and irrational). He criticized Plato, disputed his interpretation of Socrates, and sabotaged his lectures, sometimes distracting listeners by bringing food and eating during the discussions.[citation needed] Diogenes was also noted for having mocked Alexander the Great, both in public and to his face when he visited Corinth in 336 BC.[6][7][8]

Life

Nothing is known about Diogenes's early life except that his father, Hicesias, was a banker.[9] It seems likely that Diogenes was also enrolled into the banking business aiding his father.

At some point (the exact date is unknown), Hicesias and Diogenes became involved in a scandal involving the adulteration or debasement of the currency,[10] and Diogenes was exiled from the city and lost his citizenship and all his material possessions.[11][12] This aspect of the story seems to be corroborated by archaeology: large numbers of defaced coins (smashed with a large chisel stamp) have been discovered at Sinope dating from the middle of the 4th century BC, and other coins of the time bear the name of Hicesias as the official who minted them.[13] During this time there was much counterfeit money circulating in Sinope.[11] The coins were deliberately defaced in order to render them worthless as legal tender.[11] Sinope was being disputed between pro-Persian and pro-Greek factions in the 4th century, and there may have been political rather than financial motives behind the act.

Athens

According to one story,[12] Diogenes went to the Oracle at Delphi to ask for her advice and was told that he should "deface the currency". Following the debacle in Sinope, Diogenes decided that the oracle meant that he should deface the political currency rather than actual coins. He traveled to Athens and made it his life's goal to challenge established customs and values. He argued that instead of being troubled about the true nature of evil, people merely rely on customary interpretations. Diogenes arrived in Athens with a slave named Manes who escaped from him shortly thereafter. With characteristic humor, Diogenes dismissed his ill fortune by saying, "If Manes can live without Diogenes, why not Diogenes without Manes?"[14] Diogenes would mock such a relation of extreme dependency. He found the figure of a master who could do nothing for himself contemptibly helpless. He was attracted by the ascetic teaching of Antisthenes, a student of Socrates. When Diogenes asked Antisthenes to mentor him, Antisthenes ignored him and reportedly "eventually beat him off with his staff". Diogenes responded, "Strike, for you will find no wood hard enough to keep me away from you, so long as I think you've something to say." Diogenes became Antisthenes's pupil, despite the brutality with which he was initially received.[15] Whether the two ever really met is still uncertain,[16][17][18] but he surpassed his master in both reputation and the austerity of his life. He considered his avoidance of earthly pleasures a contrast to and commentary on contemporary Athenian behaviors. This attitude was grounded in a disdain for what he regarded as the folly, pretence, vanity, self-deception, and artificiality of human conduct.

The stories told of Diogenes illustrate the logical consistency of his character. He inured himself to the weather by living in a clay wine jar[5][19] belonging to the temple of Cybele.[20] He destroyed the single wooden bowl he possessed on seeing a peasant boy drink from the hollow of his hands. He then exclaimed: "Fool that I am, to have been carrying superfluous baggage all this time!".[21][22] It was contrary to Athenian customs to eat within the marketplace, and still he would eat there, for, as he explained when rebuked, it was during the time he was in the marketplace that he felt hungry. He used to stroll about in full daylight with a lamp; when asked what he was doing, he would answer, "I am looking for a man."[23] Modern sources often say that Diogenes was looking for an "honest man", but in ancient sources he is simply "looking for a man" – "ἄνθρωπον ζητῶ".[24] This has been interpreted to mean that, in his view, the unreasoning behavior of the people around him meant that they did not qualify as men. Diogenes looked for a man but reputedly found nothing but rascals and scoundrels.[25] Diogenes taught by living example. He tried to demonstrate that wisdom and happiness belong to the man who is independent of society and that civilization is regressive. He scorned not only family and socio-political organization, but also property rights and reputation. He even rejected traditional ideas about human decency. In addition to eating in the marketplace,[26] Diogenes is said to have urinated on some people who insulted him,[27] defecated in the theatre,[28] masturbated in public, and pointed at people with his middle finger, which was considered insulting.[29] Diogenes Laërtius also relates that Diogenes would spit and fart in public.[30] When asked about his eating in public Diogenes said, "If taking breakfast is nothing out of place, then it is nothing out of place in the marketplace."[31] On the indecency of his masturbating in public he would say, "If only it were as easy to banish hunger by rubbing my belly."[31]

Diogenes had nothing but disdain for Plato and his abstract philosophy.[32] Diogenes viewed Antisthenes as the true heir to Socrates, and shared his love of virtue and indifference to wealth,[33] together with a disdain for general opinion.[34] Diogenes shared Socrates's belief that he could function as doctor to men's souls and improve them morally, while at the same time holding contempt for their obtuseness. Plato once described Diogenes as "a Socrates gone mad."[35] According to Diogenes Laërtius, when Plato gave the tongue-in-cheek[36] definition of man as "featherless bipeds", Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato's Academy, saying, "Here is Plato's man" (Οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ Πλάτωνος ἄνθρωπος), and so the academy added "with broad flat nails" to the definition.[37]

Corinth

According to a story which seems to have originated with Menippus of Gadara,[38] Diogenes was captured by pirates while on voyage to Aegina and sold as a slave in Crete to a Corinthian named Xeniades. Being asked his trade, he replied that he knew no trade but that of governing men, and that he wished to be sold to a man who needed a master. Xeniades liked his spirit and hired Diogenes to tutor his children. As tutor to Xeniades's two sons,[39] it is said that he lived in Corinth for the rest of his life, which he devoted to preaching the doctrines of virtuous self-control. There are many stories about what actually happened to him after his time with Xeniades's two sons. There are stories stating he was set free after he became "a cherished member of the household", while one says he was set free almost immediately, and still another states that "he grew old and died at Xeniades's house in Corinth."[40] He is even said to have lectured to large audiences at the Isthmian Games.[41] Although most of the stories about his living in a jar[5] are located in Athens, Lucian recounts a tale where he lived in a jar near the gymnasium in Corinth.[42]

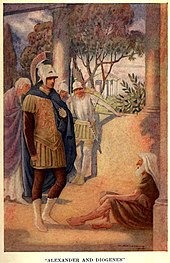

It was in Corinth that a meeting between Alexander the Great and Diogenes is supposed to have taken place.[43] These stories may be apocryphal. The accounts of Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius recount that they exchanged only a few words: while Diogenes was relaxing in the morning sunlight, Alexander, thrilled to meet the famous philosopher, asked if there was any favour he might do for him. Diogenes replied, "Yes, stand out of my sunlight." Alexander then declared, "If I were not Alexander, then I should wish to be Diogenes."[7][8] In another account of the conversation, Alexander found the philosopher looking attentively at a pile of human bones. Diogenes explained, "I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave."

Death

There are conflicting accounts of Diogenes's death. His contemporaries alleged that he held his breath until he died, although other accounts of his death say he became ill from eating raw octopus[44] or from an infected dog bite.[45] When asked how he wished to be buried, he left instructions to be thrown outside the city wall so that wild animals could feast on his body. When asked if he minded this, he said, "Not at all, as long as you provide me with a stick to chase the creatures away!" When asked how he could use the stick since he would lack awareness, he replied: "If I lack awareness, then why should I care what happens to me when I am dead?"[46] To the end, Diogenes made fun of people's excessive concern with the "proper" treatment of the dead. The Corinthians erected to his memory a pillar on which rested a dog of Parian marble.[47] It was alleged by Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius that both Diogenes and Alexander died on the same day; however, the actual death date of neither man can be verified.[48]

Philosophy

Along with Antisthenes and Crates of Thebes, Diogenes is considered one of the founders of Cynicism. The ideas of Diogenes, like those of most other Cynics, must be arrived at indirectly. Fifty-one writings of Diogenes survive as part of the spurious Cynic epistles, though he is reported to have authored over ten books and seven tragedies that do not survive.[49] Cynic ideas are inseparable from Cynic practice; therefore what is known about Diogenes is contained in anecdotes concerning his life and sayings attributed to him in a number of scattered classical sources.

Many anecdotes of Diogenes refer to his dog-like behavior and his praise of a dog's virtues. It is not known whether Diogenes was insulted with the epithet "doggish" and made a virtue of it, or whether he first took up the dog theme himself. When asked why he was called a dog he replied, "I fawn on those who give me anything, I yelp at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals."[19] One explanation offered in ancient times for why the Cynics were called dogs was that Antisthenes taught in the Cynosarges gymnasium at Athens.[50] The word Cynosarges means the place of the white dog. Later Cynics also sought to turn the word to their advantage, as a later commentator explained:

There are four reasons why the Cynics are so named. First because of the indifference of their way of life, for they make a cult of indifference and, like dogs, eat and make love in public, go barefoot, and sleep in tubs and at crossroads. The second reason is that the dog is a shameless animal, and they make a cult of shamelessness, not as being beneath modesty, but as superior to it. The third reason is that the dog is a good guard, and they guard the tenets of their philosophy. The fourth reason is that the dog is a discriminating animal which can distinguish between its friends and enemies. So do they recognize as friends those who are suited to philosophy, and receive them kindly, while those unfitted they drive away, like dogs, by barking at them.[51]

Diogenes believed human beings live hypocritically and would do well to study the dog. Besides performing natural body functions in public with ease, a dog will eat anything and makes no fuss about where to sleep. Dogs live in the present and have no use for pretentious philosophy. They know instinctively who is friend and who is foe.

Diogenes stated that "other dogs bite their enemies, I bite my friends to save them."[52] Diogenes maintained that all the artificial growths of society were incompatible with happiness and that morality implies a return to the simplicity of nature. So great was his austerity and simplicity that the Stoics would later claim him to be a wise man or "sophos". In his words, "Humans have complicated every simple gift of the gods."[53] Although Socrates had previously identified himself as belonging to the world, rather than a city,[54] Diogenes is credited with the first known use of the word "cosmopolitan". When he was asked from where he came, he replied, "I am a citizen of the world (cosmopolites)".[55] This was a radical claim in a world where a man's identity was intimately tied to his citizenship of a particular city-state. As an exile and an outcast, a man with no social identity, Diogenes made a mark on his contemporaries.

Legacy

Depictions in art

Both in ancient and in modern times, Diogenes's personality has appealed strongly to sculptors and to painters. Ancient busts exist in the museums of the Vatican, the Louvre, and the Capitol. The interview between Diogenes and Alexander is represented in an ancient marble bas-relief found in the Villa Albani. In Raphael's fresco The School of Athens, a lone reclining figure in the foreground represents Diogenes.[56]

The many allusions to dogs in Shakespeare's Timon of Athens are references to the school of Cynicism that could be interpreted as suggesting a parallel between the misanthropic hermit, Timon, and Diogenes; but Shakespeare would have had access to Michel de Montaigne's essay, "Of Democritus and Heraclitus", which emphasised their differences: Timon actively wishes men ill and shuns them as dangerous, whereas Diogenes esteems them so little that contact with them could not disturb him.[57] "Timonism" is in fact often contrasted with "Cynicism": "Cynics saw what people could be and were angered by what they had become; Timonists felt humans were hopelessly stupid & uncaring by nature and so saw no hope for change."[58]

The philosopher's name was adopted by the fictional Diogenes Club, an organization that Sherlock Holmes' brother Mycroft Holmes belongs to in the story "The Greek Interpreter" by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It is called such as its members are educated, yet untalkative and have a dislike of socialising, much like the philosopher himself.[59]

Psychology

Diogenes's name has been applied to a behavioural disorder characterised by apparently involuntary self-neglect and hoarding.[60] The disorder afflicts the elderly and is quite inappropriately named, as Diogenes deliberately rejected common standards of material comfort, and was anything but a hoarder.[61]

References

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §79

- ^ Diogenes of Sinope Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. By Julie Piering. Downloaded 14 June 2022.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 6, 18, 21; Dio Chrysostom, Orations, viii. 1–4; Aelian, x. 16; Stobaeus, Florilegium, 13.19

- ^ IEP

- ^ a b c Desmond, William (2008). Cynics. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780520258358. Archived from the original on 2017-04-29. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §32; Plutarch, Alexander, 14, On Exile, 15.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Alexander 14

- ^ a b John M. Dillon (2004). Morality and Custom in Ancient Greece. Indiana University Press. pp. 187–88. ISBN 978-0-253-34526-4.

- ^ (Laërtius 1925, §20). A trapezites was a banker/money-changer who could exchange currency, arrange loans, and was sometimes entrusted with the minting of currency.

- ^ Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, p. 226: "The word paracharaxis can be understood in various ways such as the defacement of currency or the counterfeiting of coins or the adulteration of money."

- ^ a b c Examined Lives from Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller p. 76

- ^ a b Laërtius 1925, §20–21

- ^ C. T. Seltman, Diogenes of Sinope, Son of the Banker Hikesias, in Transactions of the International Numismatic Congress 1936 (London 1938).

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §55; Seneca, De Tranquillitate Animi, 8.7.; Aelian, Varia Historia, 13.28.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §21; Aelian, Varia Historia, 10.16.; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Long 1996, p. 45

- ^ Dudley 1937, p. 2

- ^ Prince 2005, p. 77

- ^ a b Examined Lives from Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller p. 78

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §23 ; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Examined lives from Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §37; Seneca, Epistles, 90.14.; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §41

- ^ "Diogenis Laertius 6".

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §32

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §58, 69. Eating in public places was considered bad manners.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §46

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, Or. 8.36; Julian, Orations, 6.202c.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §34–35; Epictetus, Discourses, iii.2.11.

- ^ Benjamin Lee Todd, 'Apuleios Florida:A commentary, 2012, p132

- ^ a b Examined Lives from Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller p. 80

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §24

- ^ Plato, Apology Archived 2009-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, 41e.

- ^ Xenophon, Apology Archived 2009-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, 1.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §54 ; Aelian, Varia Historia, 14.33.

- ^ Desmond, William (1995). Being and the Between: Political Theory in the American Academy. SUNY Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780791422717.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §40

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §29

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §30–31

- ^ "Diogenes of Sinope". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2006-04-26. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, Or. 8.10

- ^ Lucian (1905), "3", How to Write History

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §38; Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 5.32.; Plutarch, Alexander, 14, On Exile, 15; Dio Chrysostom, Or. 4.14

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §76; Athenaeus, 8.341.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §77

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1.43.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §78; Greek Anthology, 1.285.; Pausanias, 2.2.4.

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia, 717c; Diogenes Laërtius vi. 79, citing Demetrius of Magnesia as his source. It is also reported by the Suda, Diogenes δ1143.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §80

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §13. Cf. The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, 2nd edition, p. 165.

- ^ Scholium on Aristotle's Rhetoric, quoted in Dudley 1937, p. 5

- ^ Diogenes of Sinope, quoted by Stobaeus, Florilegium, iii. 13. 44.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §44

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 5.37.; Plutarch, On Exile, 5.; Epictetus, Discourses, i.9.1.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, §63

- ^ Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling, by Ross King

- ^ Hugh Grady, "A Companion to Shakespeare's Works", Dutton. R & Howard J., Blakewell Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22632-X, pp. 443–44.

- ^ Paul Ollswang, "Cynicism: A Series of Cartoons on a Philosophical Theme", January 1988, page B at official site Archived 2012-03-22 at the Wayback Machine; repr. in The Best Comics of the Decade 1980–1990 Vol. 1, Seattle, 1990, ISBN 1-56097-035-9, p. 23.

- ^ Smith, Daniel (2014) [2009]. The Sherlock Holmes Companion: An Elementary Guide (Updated ed.). Aurum Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-78131-404-3.

- ^ Hanon C, Pinquier C, Gaddour N, Saïd S, Mathis D, Pellerin J (2004). "[Diogenes syndrome: a transnosographic approach]". Encephale (in French). 30 (4): 315–22. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(04)95443-7. PMID 15538307.

- ^ Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, p. 31

Sources

- Desmond, William D. 2008. Cynics. Acumen / University of California Press.

- Dudley, Donald R. (1937). A History of Cynicism from Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. Cambridge.

- Laërtius, Diogenes; Plutarch (1979). Herakleitos & Diogenes. Translated by Guy Davenport. Bolinas, California: Grey Fox Press. ISBN 978-0-912516-36-3.

(Contains 124 sayings of Diogenes)  Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:6. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:6. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Long, A. A. (1996). "The Socratic Tradition: Diogenes, Crates, and Hellenistic Ethics". In Bracht Branham, R.; Goulet-Cazé, Marie-Odile (eds.). The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21645-7.

- Navia, Luis E. (2005). Diogenes the Cynic : the war against the world. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books. ISBN 9781591023203.

- Prince, Susan (2005). "Socrates, Antisthenes, and the Cynics". In Ahbel-Rappe, Sara; Kamtekar, Rachana (eds.). A Companion to Socrates. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0863-8.

- Sloterdijk, Peter (1987). Critique of Cynical Reason. Translation by Michael Eldred; foreword by Andreas Huyssen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1586-5.

Further reading

- Cutler, Ian (2005). Cynicism from Diogenes to Dilbert. Jefferson, Va.: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-2093-3.

- Mazella, David (2007). The making of modern cynicism. Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2615-5.

- Navia, Luis E. (1996). Classical cynicism : a critical study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30015-8.

- Navia, Luis E. (1998). Diogenes of Sinope : the man in the tub. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30672-3.

- Hard, Robin (2012). Diogenes the Cynic: Sayings and Anecdotes, With Other Popular Moralists, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958924-1

- Roubineau, Jean-Manuel; DeBevoise, Malcolm; Mitsis, Philip (2023). The dangerous life and ideas of Diogenes the Cynic. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197666357.

- Shea, Louisa (2010). The cynic enlightenment : Diogenes in the salon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9385-8.

External links

- "Diogenes of Sinope". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Lives & Writings on the Cynics, directory of literary references to Ancient Cynics

- A day with Diogenes

- Diogenes The Dog from Millions of Mouths

- Diogenes of Sinope

- James Grout: Diogenes the Cynic, part of the Encyclopædia Romana