Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name Bis(2-ethylhexyl) benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.829 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C24H38O4 | |||

| Molar mass | 390.564 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless, oily liquid[3] | ||

| Density | 0.99 g/mL (20°C)[3] | ||

| Melting point | −50 °C (−58 °F; 223 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 385 °C (725 °F; 658 K) | ||

| 0.00003% (23.8 °C)[3] | |||

| Vapor pressure | < 0.01 mmHg (20 °C)[3] | ||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.4870[4] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards |

Irritant, teratogen | ||

| GHS labelling:[6] | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H360FD | |||

| P201, P202, P280, P308+P313, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 216 °C; 420 °F; 489 K (open cup)[3] | ||

| Explosive limits | 0.3%-?[3] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

34,000 mg/kg (oral, rabbit) 26,000 mg/kg (oral, guinea pig) 30,600 mg/kg (oral, rat) 30,000 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[5] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[3] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

Ca TWA 5 mg/m3 ST 10 mg/m3[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

Ca [5000 mg/m3][3] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, diethylhexyl phthalate, diisooctyl phthalate, DEHP; incorrectly — dioctyl phthalate, DIOP) is an organic compound with the formula C6H4(CO2C8H17)2. DEHP is the most common member of the class of phthalates, which are used as plasticizers. It is the diester of phthalic acid and the branched-chain 2-ethylhexanol. This colorless viscous liquid is soluble in oil, but not in water.

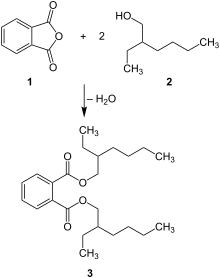

Production

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate is produced commercially by the reaction of excess 2-ethylhexanol with phthalic anhydride in the presence of an acid catalyst such as sulfuric acid or para-toluenesulfonic acid. It was first produced in commercial quantities in Japan circa 1933 and in the United States in 1939.[7]

DEHP has two stereocenters,[8] located at the carbon atoms carrying the ethyl groups. As a result, it has three distinct stereoisomers,[8] consisting of an (R,R) form, an (S,S) form (diastereomers), and a meso (R, S) form. As most 2-ethylhexanol is produced as a racemic mixture, commercially-produced DEHP is therefore racemic as well, and consists of a 1:1:2 statistical mixture of stereoisomers.

Use

Due to its suitable properties and the low cost, DEHP is widely used as a plasticizer in manufacturing of articles made of PVC.[9] Plastics may contain 1% to 40% of DEHP. It is also used as a hydraulic fluid and as a dielectric fluid in capacitors. DEHP also finds use as a solvent in glowsticks.

Approximately three million tonnes are produced and used annually worldwide.[9]

Manufacturers of flexible PVC articles can choose among several alternative plasticizers offering similar technical properties as DEHP. These alternatives include other phthalates such as diisononyl phthalate (DINP), di-2-propyl heptyl phthalate (DPHP), diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP), and non-phthalates such as 1,2-cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid diisononyl ester (DINCH), dioctyl terephthalate (DOTP), and citrate esters.[10]

Environmental exposure

DEHP is a component of many household items, including tablecloths, floor tiles, shower curtains, garden hoses, rainwear, dolls, toys, shoes, medical tubing, furniture upholstery, and swimming pool liners.[11] DEHP is an indoor air pollutant in homes and schools. Common exposures come from the use of DEHP as a fragrance carrier in cosmetics, personal care products, laundry detergents, colognes, scented candles, and air fresheners.[12] The most common exposure to DEHP comes through food with an average consumption of 0.25 milligrams per day.[13] It can also leach into a liquid that comes in contact with the plastic; it extracts faster into nonpolar solvents (e.g. oils and fats in foods packed in PVC). Fatty foods that are packaged in plastics that contain DEHP are more likely to have higher concentrations such as milk products, fish or seafood, and oils.[11] The US FDA therefore permits use of DEHP-containing packaging only for foods that primarily contain water.

DEHP can leach into drinking water from discharges from rubber and chemical factories; The US EPA limits for DEHP in drinking water is 6 ppb.[13] It is also commonly found in bottled water, but unlike tap water, the EPA does not regulate levels in bottled water.[12] DEHP levels in some European samples of milk, were found at 2000 times higher than the EPA Safe Drinking Water limits (12,000 ppb). Levels of DEHP in some European cheeses and creams were even higher, up to 200,000 ppb, in 1994.[14] Additionally, workers in factories that utilize DEHP in production experience greater exposure.[11] The U.S. agency OSHA's limit for occupational exposure is 5 mg/m3 of air.[15]

Use in medical devices

DEHP is the most common phthalate plasticizer in medical devices such as intravenous tubing and bags, IV catheters, nasogastric tubes, dialysis bags and tubing, blood bags and transfusion tubing, and air tubes. DEHP makes these plastics softer and more flexible and was first introduced in the 1940s in blood bags. For this reason, concern has been expressed about leachates of DEHP transported into the patient, especially for those requiring extensive infusions or those who are at the highest risk of developmental abnormalities, e.g. newborns in intensive care nursery settings, hemophiliacs, kidney dialysis patients, neonates, premature babies, lactating, and pregnant women. According to the European Commission Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER), exposure to DEHP may exceed the tolerable daily intake in some specific population groups, namely people exposed through medical procedures such as kidney dialysis.[16] The American Academy of Pediatrics has advocated not to use medical devices that can leach DEHP into patients and, instead, to resort to DEHP-free alternatives.[17] In July 2002, the U.S. FDA issued a Public Health Notification on DEHP, stating in part, "We recommend considering such alternatives when these high-risk procedures are to be performed on male neonates, pregnant women who are carrying male fetuses, and peripubertal males" noting that the alternatives were to look for non-DEHP exposure solutions;[18] they mention a database of alternatives.[19] The CBC documentary The Disappearing Male raised concerns about sexual development in male fetal development, miscarriage, and as a cause of dramatically lower sperm counts in men.[20] A review article in 2010 in the Journal of Transfusion Medicine showed a consensus that the benefits of lifesaving treatments with these devices far outweigh the risks of DEHP leaching out of these devices. Although more research is needed to develop alternatives to DEHP that gives the same benefits of being soft and flexible, which are required for most medical procedures, if a procedure requires one of these devices and if patient is at high risk to suffer from DEHP then a DEHP alternative should be considered if medically safe.[21]

Metabolism

DEHP hydrolyzes to mono-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) and subsequently to phthalate salts. The released alcohol is susceptible to oxidation to the aldehyde and carboxylic acid.[9]

Effects on living organisms

Toxicity

The acute toxicity of DEHP is low in animal models: 30 g/kg in rats (oral) and 24 g/kg in rabbits (dermal).[9] Concerns instead focus on its potential as an endocrine disruptor.

Endocrine disruption

DEHP, along with other phthalates, is believed to cause endocrine disruption in males, through its action as an androgen antagonist,[22] and may have lasting effects on reproductive function, for both childhood and adult exposures. Prenatal phthalate exposure has been shown to be associated with lower levels of reproductive function in adolescent males.[23] In another study, airborne concentrations of DEHP at a PVC pellet plant were significantly associated with a reduction in sperm motility and chromatin DNA integrity.[24] Additionally, the authors noted the daily intake estimates for DEHP were comparable to the general population, indicating a "high percentage of men are exposed to levels of DEHP that may affect sperm motility and chromatin DNA integrity". The claims have received support by a study[25] using dogs as a "sentinel species to approximate human exposure to a selection of chemical mixtures present in the environment". The authors analyzed the concentration of DEHP and other common chemicals such as PCBs in testes from dogs from five different world regions. The results showed that regional differences in concentration of the chemicals are reflected in dog testes and that pathologies such as tubule atrophy and germ cells were more prevalent in testes of dogs from regions with higher concentrations.

Development

Numerous studies of DEHP have shown changes in sexual function and development in mice and rats. DEHP exposure during pregnancy has been shown to disrupt placental growth and development in mice, resulting in higher rates of low birthweight, premature birth, and fetal loss.[26] In a separate study, exposure of neonatal mice to DEHP through lactation caused hypertrophy of the adrenal glands and higher levels of anxiety during puberty.[27] In another study, pubertal administration of higher-dose DEHP delayed puberty in rats, reduced testosterone production, and inhibited androgen-dependent development; low doses showed no effect.[28]

Obesity

When DEHP is ingested intestinal lipases convert it to MEHP, which then is absorbed. MEHP is suspected to have an obesogenic effect. Rodent studies and human studies have shown DEHP to be a possible disruptor of thyroid function, which plays a key role in energy balance and metabolism. Exposure to DEHP has been associated with lower plasma thyroxine levels and decreased uptake of iodine in thyroid follicular cells. Previous studies have shown that slight changes in thyroxine levels can have dramatic effects on resting energy expenditure, similar to that of patients with hypothyroidism, which has been shown to cause increased weight gain in those study populations.[29]

Cardiotoxicity

Even at relatively low doses of DEHP, cardiovascular reactivity was significantly affected in mice.[30] A clinically relevant dose and duration of exposure to DEHP has been shown to have a significant impact on the behavior of cardiac cells in culture. This includes an uncoupling effect that leads to irregular rhythms in vitro. Untreated cells had fast conduction velocity, along with homogenous activation wave fronts and synchronized beating. Cells treated with DEHP exhibited fractured wave fronts with slow propagation speeds. This is observed in conjunction with a significant decrease in the amount of expression and instability of gap junctional connexin proteins, specifically connexin-43, in cardiomyocytes treated with DEHP.[31]

The decrease in expression and instability of connexin-43 may be due to the down regulation of tubulin and kinesin genes, and the alteration of microtubule structure, caused by DEHP; all of which are responsible for the transport of protein products. Also, DEHP caused down regulation of several growth factors, such as angiotensinogen, transforming growth factor-beta, vascular endothelial growth factor C and A, and endothelial-1. The DEHP-induced down regulation of these growth factors may also contribute to the reduced expression and instability of connexin-43.[32]

DEHP has also been shown, in vitro using cardiac muscle cells, to cause activation of PPAR-alpha gene, which is a key regulator in lipid metabolism and peroxisome proliferation; both of which can be involved in atherosclerosis and hyperlipidemia, which are precursors of cardiovascular disease.[33]

Once metabolized into MEHP, the molecule has been shown to lengthen action potential duration and slow epicardial conduction velocity in Langendorff perfused rodent hearts.[34]

Other health effects

Studies in mice have shown other adverse health effects due to DEHP exposure. Ingestion of 0.01% DEHP caused damage to the blood-testis barrier as well as induction of experimental autoimmune orchitis.[35] There is also a correlation between DEHP plasma levels in women and endometriosis.[36]

DEHP is also a possible cancer causing agent in humans, although human studies remain inconclusive, due to the exposure of multiple elements and limited research. In vitro and rodent studies indicate that DEHP is involved in many molecular events, including increased cell proliferation, decreased apoptosis, oxidative damage, and selective clonal expansion of the initiated cells; all of which take place in multiple sites of the human body.[37]

Government and industry response

Taiwan

In October 2009, Consumers' Foundation, Taiwan (CFCT) published test results[38] that found 5 out of the sampled 12 shoes contained over 0.1% of phthalate plasticizer content, including DEHP, which exceeds the government's Toy Safety Standard (CNS 4797). CFCT recommend that users should first wear socks to avoid direct skin contact.

In May 2011, the illegal use of the plasticizer DEHP in clouding agents for use in food and beverages has been reported in Taiwan.[39] An inspection of products initially discovered the presence of plasticizers. As more products were tested, inspectors found more manufacturers using DEHP and DINP.[40] The Department of Health confirmed that contaminated food and beverages had been exported to other countries and regions, which reveals the widespread prevalence of toxic plasticizers.

European Union

Concerns about chemicals ingested by children when chewing plastic toys prompted the European Commission to order a temporary ban on phthalates in 1999, the decision of which is based on an opinion by the Commission's Scientific Committee on Toxicity, Ecotoxicity and the Environment (CSTEE). A proposal to make the ban permanent was tabled. Until 2004, EU banned the use of DEHP along with several other phthalates (DBP, BBP, DINP, DIDP and DNOP) in toys for young children.[41] In 2005, the Council and the Parliament compromised to propose a ban on three types of phthalates (DINP, DIDP, and DNOP) "in toys and childcare articles which can be placed in the mouth by children". Therefore, more products than initially planned will thus be affected by the directive.[42] In 2008, six substances were considered to be of very high concern (SVHCs) and added to the Candidate List including musk xylene, MDA, HBCDD, DEHP, BBP, and DBP. In 2011, those six substances have been listed for Authorization in Annex XIV of REACH by Regulation (EU) No 143/2011.[43] According to the regulation, phthalates including DEHP, BBP and DBP will be banned from February 2015.[44]

In 2012, Danish Environment Minister Ida Auken announced the ban of DEHP, DBP, DIBP and BBP, pushing Denmark ahead of the European Union which has already started a process of phasing out phthalates.[45] However, it was postponed by two years and would take effect in 2015 and not in December 2013, which was the initial plan. The reason is that the four phthalates are far more common than expected and that producers cannot phase out phthalates as fast as the Ministry of Environment requested.[46]

In 2012, France became the first country in the EU to ban the use of DEHP in pediatrics, neonatal, and maternity wards in hospitals.[47]

DEHP has now been classified as a Category 1B reprotoxin,[48] and is now on the Annex XIV of the European Union's REACH legislation. DEHP has been phased out in Europe under REACH[49] and can only be used in specific cases if an authorization has been granted. Authorizations are granted by the European Commission, after obtaining the opinion of the Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) and the Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA).

California

DEHP is classified as a "chemical known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm" (in this case, both) under the terms of Proposition 65.[50]

References

- ^ Diethylhexyl ester of phthalic acid

- ^ Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate

- ^ a b c d e f g h i NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0236". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Alfa Aesar. "117-81-7 - Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, 98+% - Dioctyl phthalate - Phthalic acid bis(2-ethylhexyl)ester - A10415". www.alfa.com. Thermo Fisher Scientific. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Di-sec octyl phthalate". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 4 December 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Sigma-Aldrich Co., Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Retrieved on 2022-05-12.

- ^ IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans Volume 29: Some industrial chemicals and dyestuffs (PDF). [Lyon]: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1982. p. 271. ISBN 978-92-832-1229-4.

- ^ a b Sheikh, I. A. (2016) Stereoselectivity and the potential endocrine disrupting activity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) against human progesterone receptor: a computational perspective. Journal of applied toxicology. 36 (5), 741–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.3302

- ^ a b c d e Lorz, Peter M.; Towae, Friedrich K.; Enke, Walter; et al. (2007). "Phthalic Acid and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_181.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ "Plasticizers | ExxonMobil Product Solutions". www.exxonmobilchemical.com. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ a b c "ATSDR - ToxFAQs™: Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)". www.atsdr.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ a b "EHHI :: Plastics :: EHHI Releases Original Research Report:Plastics That May be Harmful to Children and Reproductive Health". www.ehhi.org. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ a b OW, US EPA (21 September 2015). "Basic Information about Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in Drinking Water". water.epa.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ Sharman, M; Read, WA; Castle, L; Gilbert, J (1994). "Levels of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and total phthalate esters in milk, cream, butter and cheese". Food Additives and Contaminants. 11 (3): 375–85. doi:10.1080/02652039409374236. PMID 7926171.

- ^ "Chemical Sampling Information | Di-(2-Ethylhexyl)phthalate". www.osha.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-07-31. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Phthalates in school supplies". GreenFacts Website. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Shea, Katherine M. (2003). "Pediatric exposure and potential toxicity of phthalate plasticizers". Pediatrics. 111 (6 Pt 1): 1467–74. doi:10.1542/peds.111.6.1467. PMID 12777573.

- ^ FDA Public Health Notification: PVC Devices Containing the Plasticizer DEHP, USFDA July 12, 2002

- ^ Products for Hazard: DEHP Archived 2010-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Sustainable Hospitals

- ^ The Disappearing Male – Sunday February 14, 2010 at 3 pm on CBC-TV, CBC

- ^ Sampson, J; de Korte, D (2011). "DEHP-plasticised PVC: relevance to blood services". Transfusion Medicine. 21 (2): 73–83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.01056.x. PMID 21143327. S2CID 32481051.

- ^ CDC Main (7 September 2021). "Biomonitoring Summary Phthalates Overview".

- ^ Axelsson, Jonatan; Rylander, Lars; Rignell-Hydbom, Anna; et al. (2015). "Prenatal phthalate exposure and reproductive function in young men". Environmental Research. 138: 264–70. Bibcode:2015ER....138..264A. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.02.024. PMID 25743932.

- ^ Huang, Li-Ping; Lee, Ching-Chang; Hsu, Ping-Chi; Shih, Tung-Sheng (2011). "The association between semen quality in workers and the concentration of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in polyvinyl chloride pellet plant air". Fertility and Sterility. 96 (1): 90–4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.093. PMID 21621774.

- ^ Sumner, R.N.; Byers, A.; Zhang, Z. (2021). "Environmental chemicals in dog testes reflect their geographical source and may be associated with altered pathology". Scientific Reports. 11 (7361): 7361. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.7361S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86805-y. PMC 8016893. PMID 33795811.

- ^ Lin, Ming-Lu; Wang, Dean-Chuan; Chen, Shih-Chieh (April 2013). "Lactational exposure to DEHP induced adrenocortical hypertrophy and anxiety-like behavior in rats". The FASEB Journal. 27 (1 Supplement): 936.15. doi:10.1096/fasebj.27.1_supplement.936.15.

- ^ Zong, Teng; Lai, Lidan; Hu, Jia; et al. (2015). "Maternal exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate disrupts placental growth and development in pregnant mice". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 297: 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.065. PMID 25935407.

- ^ Noriega, N. C.; Howdeshell, K. L.; Furr, J.; et al. (2009). "Pubertal Administration of DEHP Delays Puberty, Suppresses Testosterone Production, and Inhibits Reproductive Tract Development in Male Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans Rats". Toxicological Sciences. 111 (1): 163–78. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp129. PMID 19528224.

- ^ Kim, Shin Hye; Park, Mi Jung (2014). "Phthalate exposure and childhood obesity". Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 19 (2): 69–75. doi:10.6065/apem.2014.19.2.69. PMC 4114051. PMID 25077088.

- ^ Jaimes, Rafael (2017). "Plastics and cardiovascular health: phthalates may disrupt heart rate variability and cardiovascular reactivity". Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 313 (5): H1044 – H1053. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00364.2017. PMC 5792203. PMID 28842438.

- ^ Gillum, Nikki; Karabekian, Zaruhi; Swift, Luther M.; et al. (2009). "Clinically relevant concentrations of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) uncouple cardiac syncytium". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 236 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.027. PMC 2670944. PMID 19344669.

- ^ Yang, Oneyeol; Kim, Hye Lim; Weon, Jong-Il; Seo, Young Rok (2015). "Endocrine-disrupting Chemicals: Review of Toxicological Mechanisms Using Molecular Pathway Analysis". Journal of Cancer Prevention. 20 (1): 12–24. doi:10.15430/JCP.2015.20.1.12. PMC 4384711. PMID 25853100.

- ^ Posnack, Nikki Gillum; Lee, Norman H.; Brown, Ronald; Sarvazyan, Narine (2011). "Gene expression profiling of DEHP-treated cardiomyocytes reveals potential causes of phthalate arrhythmogenicity". Toxicology. 279 (1–3): 54–64. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2010.09.007. PMC 3003946. PMID 20920545.

- ^ Jaimes III, R; McCullough, D.; Siegel, B.; et al. (2019). "Plasticizer Interaction with the Heart: Chemicals Used in Plastic Medical Devices Can Interfere with Cardiac Electrophysiology". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 12 (7): e007294. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007294. PMC 6693678. PMID 31248280.

- ^ Hirai, Shuichi; Naito, Munekazu; Kuramasu, Miyuki; et al. (2015). "Low-dose exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) increases susceptibility to testicular autoimmunity in mice". Reproductive Biology. 15 (3): 163–71. doi:10.1016/j.repbio.2015.06.004. PMID 26370459.

- ^ Kim, Sung Hoon; Chun, Sail; Jang, Jin Yeon; et al. (2011). "Increased plasma levels of phthalate esters in women with advanced-stage endometriosis: a prospective case-control study". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (1): 357–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1059. PMID 20797718.

- ^ Rusyn, Ivan; Corton, J. Christopher (2012). "Mechanistic considerations for human relevance of cancer hazard of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate". Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 750 (2): 141–58. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.12.004. PMC 3348351. PMID 22198209.

- ^ 《消費者報導雜誌》342期 第4至11頁「跟著流行走?踩著危機走!園丁鞋逾4成可塑劑超量」 (in Chinese). Consumers’ Foundation, Taiwan (CFCT).

- ^ FOOD SCARE WIDENS:Tainted additives used for two decades: manufacturer, Taipei Times, May 29, 2011

- ^ 生活中心綜合報導 (2011-05-23). 塑化劑危機!台灣海洋深層水等4廠商飲料緊急下架 (in Chinese). NOWnews. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ^ "EU ministers agree to ban chemicals in toys". EurActiv.com. 2004-10-07.

- ^ "Phthalates to be banned in toys and childcare articles". EurActiv.com. 2005-06-27. Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ^ REACH - First Six Substances Subject To Authorisation (PDF), Sparkle, vol. 559, Intertek, 25 Feb 2011

- ^ "First REACH substance bans to apply from 2014". European Solvents Industry Group. 2011-02-18. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ^ "Denmark defies EU with planned ban on phthalate chemicals". EurActiv.com. 2012-08-27.

- ^ "Danish prohibition against four low molecular weight phthalates postponed" (Press release). European Council for Plasticisers and Intermediates. Danish Environment Ministry. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- ^ "The legacy of Healthier Hospitals". practicegreenhealth.org. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ "Classifications - CL Inventory". echa.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ "Timeline of European regulations on DEHP" (PDF). PVC Med Alliance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ "Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)". oehha.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-07-30. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

Further reading

- Maradonna, Francesca; Evangelisti, Matteo; Gioacchini, Giorgia; et al. (2013). "Assay of vtg, ERs and PPARs as endpoint for the rapid in vitro screening of the harmful effect of Di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate (DEHP) and phthalic acid (PA) in zebrafish primary hepatocyte cultures". Toxicology in Vitro. 27 (1): 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2012.09.018. PMID 23063876.

External links

- FDA Public Health Notification: PVC devices containing the plasticizer DEHP (archived page)

- ATSDR ToxFAQs

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- National Pollutant Inventory - DEHP fact sheet

- Healthcare without Harm - PVC and DEHP accessed 25 March 2014

- Healthcare without Harm: "Weight of the Evidence on DEHP: Exposures are a Cause for Concern, Especially During Medical Care"; 6p-fact sheet, 16 March 2009 accessed 25 March 2014

- Spectrum Laboratories Fact Sheet (archived page)

- ChemSub Online : Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate -DEHP

- Safety Assessment of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) Released from PVC Medical Devices - Center for Devices and Radiological Health U.S. Food and Drug Administration (archived page)