Swallowing

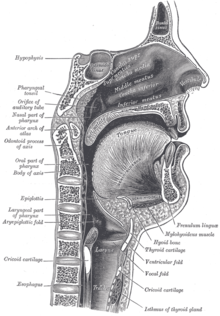

Swallowing, also called deglutition or inglutition[1] in scientific contexts, is the process in the body of a human that allows for a substance to pass from the mouth, to the pharynx, and into the esophagus, while shutting the epiglottis. Swallowing is an important part of eating and drinking. If the process fails and the material (such as food, drink, or medicine) goes through the trachea, then choking or pulmonary aspiration can occur. In the human body the automatic temporary closing of the epiglottis is controlled by the swallowing reflex.

The portion of food, drink, or other material that will move through the neck in one swallow is called a bolus.

In colloquial English, the term "swallowing" is also used to describe the action of taking in a large mouthful of food without any biting.

In humans

Swallowing comes so easily to most people that the process rarely prompts much thought. However, from the viewpoints of physiology, of speech–language pathology, and of health care for people with difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia), it is an interesting topic with extensive scientific literature.

Coordination and control

Eating and swallowing are complex neuromuscular activities consisting essentially of three phases, an oral, pharyngeal and esophageal phase. Each phase is controlled by a different neurological mechanism. The oral phase, which is entirely voluntary, is mainly controlled by the medial temporal lobes and limbic system of the cerebral cortex with contributions from the motor cortex and other cortical areas. The pharyngeal swallow is started by the oral phase and subsequently is coordinated by the swallowing center on the medulla oblongata and pons. The reflex is initiated by touch receptors in the pharynx as a bolus of food is pushed to the back of the mouth by the tongue, or by stimulation of the palate (palatal reflex).

Swallowing is a complex mechanism using both skeletal muscle (tongue) and smooth muscles of the pharynx and esophagus. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) coordinates this process in the pharyngeal and esophageal phases.

Phases

Oral phase

Prior to the following stages of the oral phase, the mandible depresses and the lips abduct to allow food or liquid to enter the oral cavity. Upon entering the oral cavity, the mandible elevates and the lips adduct to assist in oral containment of the food and liquid. The following stages describe the normal and necessary actions to form the bolus, which is defined as the state of the food in which it is ready to be swallowed.

1) Moistening

Food is moistened by saliva from the salivary glands (parasympathetic).

2) Mastication

Food is mechanically broken down by the action of the teeth controlled by the muscles of mastication (V3) acting on the temporomandibular joint. This results in a bolus which is moved from one side of the oral cavity to the other by the tongue. Buccinator (VII) helps to contain the food against the occlusal surfaces of the teeth. The bolus is ready for swallowing when it is held together by saliva (largely mucus), sensed by the lingual nerve of the tongue (VII—chorda tympani and IX—lesser petrosal) (V3). Any food that is too dry to form a bolus will not be swallowed.

3) Trough formation

A trough is then formed at the back of the tongue by the intrinsic muscles (XII). The trough obliterates against the hard palate from front to back, forcing the bolus to the back of the tongue. The intrinsic muscles of the tongue (XII) contract to make a trough (a longitudinal concave fold) at the back of the tongue. The tongue is then elevated to the roof of the mouth (by the mylohyoid (mylohyoid nerve—V3), genioglossus, styloglossus and hyoglossus (the rest XII)) such that the tongue slopes downwards posteriorly. The contraction of the genioglossus and styloglossus (both XII) also contributes to the formation of the central trough.

4) Movement of the bolus posteriorly

At the end of the oral preparatory phase, the food bolus has been formed and is ready to be propelled posteriorly into the pharynx. In order for anterior to posterior transit of the bolus to occur, orbicularis oris contracts and adducts the lips to form a tight seal of the oral cavity. Next, the superior longitudinal muscle elevates the apex of the tongue to make contact with the hard palate and the bolus is propelled to the posterior portion of the oral cavity. Once the bolus reaches the palatoglossal arch of the oropharynx, the pharyngeal phase, which is reflex and involuntary, then begins. Receptors initiating this reflex are proprioceptive (afferent limb of reflex is IX and efferent limb is the pharyngeal plexus- IX and X). They are scattered over the base of the tongue, the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches, the tonsillar fossa, uvula and posterior pharyngeal wall. Stimuli from the receptors of this phase then provoke the pharyngeal phase. In fact, it has been shown that the swallowing reflex can be initiated entirely by peripheral stimulation of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. This phase is voluntary and involves important cranial nerves: V (trigeminal), VII (facial) and XII (hypoglossal).

Pharyngeal phase

For the pharyngeal phase to work properly all other egress from the pharynx must be occluded—this includes the nasopharynx and the larynx. When the pharyngeal phase begins, other activities such as chewing, breathing, coughing and vomiting are concomitantly inhibited.

5) Closure of the nasopharynx

The soft palate is tensed by tensor palatini (Vc), and then elevated by levator palatini (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) to close the nasopharynx. There is also the simultaneous approximation of the walls of the pharynx to the posterior free border of the soft palate, which is carried out by the palatopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) and the upper part of the superior constrictor (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X).

6) The pharynx prepares to receive the bolus

The pharynx is pulled upwards and forwards by the suprahyoid and longitudinal pharyngeal muscles – stylopharyngeus (IX), salpingopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) and palatopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) to receive the bolus. The palatopharyngeal folds on each side of the pharynx are brought close together through the superior constrictor muscles, so that only a small bolus can pass.

7) Opening of the auditory tube

The actions of the levator palatini (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X), tensor palatini (Vc) and salpingopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) in the closure of the nasopharynx and elevation of the pharynx opens the auditory tube, which equalises the pressure between the nasopharynx and the middle ear. This does not contribute to swallowing, but happens as a consequence of it.

8) Closure of the oropharynx

The oropharynx is kept closed by palatoglossus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X), the intrinsic muscles of tongue (XII) and styloglossus (XII).

9) Laryngeal closure

The primary laryngopharyngeal protective mechanism to prevent aspiration during swallowing is via the closure of the true vocal folds. The adduction of the vocal cords is affected by the contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoids and the oblique and transverse arytenoids (all recurrent laryngeal nerve of vagus). Since the true vocal folds adduct during the swallow, a finite period of apnea (swallowing apnea) must necessarily take place with each swallow. When relating swallowing to respiration, it has been demonstrated that swallowing occurs most often during expiration, even at full expiration a fine air jet is expired probably to clear the upper larynx from food remnants or liquid. The clinical significance of this finding is that patients with a baseline of compromised lung function will, over a period of time, develop respiratory distress as a meal progresses. Subsequently, false vocal fold adduction, adduction of the aryepiglottic folds and retroversion of the epiglottis take place. The aryepiglotticus (recurrent laryngeal nerve of vagus) contracts, causing the arytenoids to appose each other (closes the laryngeal aditus by bringing the aryepiglottic folds together), and draws the epiglottis down to bring its lower half into contact with arytenoids, thus closing the aditus. Retroversion of the epiglottis, while not the primary mechanism of protecting the airway from laryngeal penetration and aspiration, acts to anatomically direct the food bolus laterally towards the piriform fossa. Additionally, the larynx is pulled up with the pharynx under the tongue by stylopharyngeus (IX), salpingopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X), palatopharyngeus (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X) and inferior constrictor (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X). This phase is passively controlled reflexively and involves cranial nerves V, X (vagus), XI (accessory) and XII (hypoglossal). The respiratory center of the medulla is directly inhibited by the swallowing center for the very brief time that it takes to swallow. This means that it is briefly impossible to breathe during this phase of swallowing and the moment where breathing is prevented is known as deglutition apnea.

10) Hyoid elevation

The hyoid is elevated by digastric (V & VII) and stylohyoid (VII), lifting the pharynx and larynx up even further.

11) Bolus transits pharynx

The bolus moves down towards the esophagus by pharyngeal peristalsis which takes place by sequential contraction of the superior, middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles (pharyngeal plexus—IX, X). The lower part of the inferior constrictor (cricopharyngeus) is normally closed and only opens for the advancing bolus. Gravity plays only a small part in the upright position—in fact, it is possible to swallow solid food even when standing on one's head. The velocity through the pharynx depends on a number of factors such as viscosity and volume of the bolus. In one study, bolus velocity in healthy adults was measured to be approximately 30–40 cm/s.[2]

Esophageal phase

12) Esophageal peristalsis

Like the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, the esophageal phase of swallowing is under involuntary neuromuscular control. However, propagation of the food bolus is significantly slower than in the pharynx. The bolus enters the esophagus and is propelled downwards first by striated muscle (recurrent laryngeal, X) then by the smooth muscle (X) at a rate of 3–5 cm/s. The upper esophageal sphincter relaxes to let food pass, after which various striated constrictor muscles of the pharynx as well as peristalsis and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter sequentially push the bolus of food through the esophagus into the stomach.

13) Relaxation phase

Finally the larynx and pharynx move down with the hyoid mostly by elastic recoil. Then the larynx and pharynx move down from the hyoid to their relaxed positions by elastic recoil. Swallowing therefore depends on coordinated interplay between many various muscles, and although the initial part of swallowing is under voluntary control, once the deglutition process is started, it is quite hard to stop it.

Clinical significance

Swallowing becomes a great concern for the elderly since strokes and Alzheimer's disease can interfere with the autonomic nervous system. Speech pathologists commonly diagnose and treat this condition since the speech process uses the same neuromuscular structures as swallowing. Diagnostic procedures commonly performed by a speech pathologist to evaluate dysphagia include Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing and Modified Barium Swallow Study. Occupational Therapists may also offer swallowing rehabilitation services as well as prescribing modified feeding techniques and utensils. Consultation with a dietician is essential, in order to ensure that the individual with dysphagia is able to consume sufficient calories and nutrients to maintain health. In terminally ill patients, a failure of the reflex to swallow leads to a build-up of mucus or saliva in the throat and airways, producing a noise known as a death rattle (not to be confused with agonal respiration, which is an abnormal pattern of breathing due to cerebral ischemia or hypoxia).

Abnormalities of the pharynx and/or oral cavity may lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia. Abnormalities of the esophagus may lead to esophageal dysphagia. The failure of the lower esophagus sphincter to respond properly to swallowing is called achalasia.

M-Type Swallowing

With practice, people can learn to swallow fluidly without closing the mouth by merely manipulating the tongue and jaw to drive fluids or foods down the esophagus. With a continuous motion, an individual forges breathing and priorities the swallowed matter. This intermediate level of muscle manipulation is similar to the techniques used by sword swallowers.

In non-mammal animals

In many birds, the esophagus is largely a mere gravity chute, and in such events as a seagull swallowing a fish or a stork swallowing a frog, swallowing consists largely of the bird lifting its head with its beak pointing up and guiding the prey with tongue and jaws so that the prey slides inside and down.

In fish, the tongue is largely bony and much less mobile and getting the food to the back of the pharynx is helped by pumping water in its mouth and out of its gills.

In snakes, the work of swallowing is done by raking with the lower jaw until the prey is far enough back to be helped down by body undulations.

See also

References

- ^ "inglutition". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Clave, P.; De Kraa, M.; Arreola, V.; Girvent, M.; Farre, R.; Palomera, E.; Serra-Prat, M. (2006). "The effect of bolus viscosity on swallowing function in neurogenic dysphagia". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 24 (9). Wiley: 1385–1394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03118.x. PMID 17059520. S2CID 22881225.

External links

- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch3/s6ch3_15". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- Overview at nature.com

- Anatomy and physiology of swallowing at dysphagia.com

- Swallowing animation (flash) at hopkins-gi.org

- [Article on French Wikipedia] See : "déglutition atypique" = unfunctional or pathological swallowing.

- Normal Swallowing and Dysphagia: Pediatric Population