Dean Byington

Dean Byington | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1958 |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Santa Cruz |

| Known for | Painting, works on paper, collage |

| Website | Dean Byington |

Dean Byington (born 1958), is a visual artist based in the San Francisco Bay Area.[1][2] He is known for large, hyper-detailed mixed-media paintings and paper collages of labyrinthine landscapes and invented universes that serve as settings for enigmatic allegories on nature, culture, time and humanity's effect on the planet.[3][4][5][6] Seamless amalgams of images reworked from diverse sources, including his own stylized drawings, his art evokes fairy tales gone awry, the precision of centuries-old etchings and cartographic detail, and utopian and dystopian science-fiction.[7][8][9] In 2017, critic Shana Nys Dambrot wrote, "achieving a profound, operatic feat of scale, density, and clarity … Byington’s surrealism is that of dreams and memories, with an internal logic that unifies Eastern and Western antiquity, the consequences of climate change, the engineering of urban sprawl, and the limited role of culture in making sense of the soul- and soil-crushing weight of all that civilization."[3]

Byington's work belongs to the public art collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago and Berkeley Art Museum, among others.[10][11][12][13] He has exhibited at the San Jose Museum of Art,[10] Nevada Museum of Art,[14] San Antonio Museum of Art,[4] Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,[15] Frist Art Museum[16] and Katzen Arts Center.[17]

Early life and career

Byington was born in 1958 in Santa Monica, California. His parents participated in the Manhattan Project. His father, an engineer, worked at Los Alamos and on the instrumentation at the Nevada test sites; his mother was a geologist and served as one of Robert Oppenheimer's secretaries.[4][16][18] Byington grew up in Culver City, California, exploring the full-scale outdoor sets of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Desilu Studios as an adolescent; the influence of that experience and his parents' history is discernible in various cinematic, geological and apocalyptic aspects of his art.[2][4][16][18] In 1980, he received a BA and certificate of art from the University of California, Santa Cruz. He earned an MA and MFA from the University of California, Berkeley in 1987 and 1988.[1][19]

Byington's early works were large photographic assemblages composed by projecting old daguerreotypes (of military technologies, UFOs and historical events among other subjects) piecemeal onto canvas and acetate painted with photo emulsion.[20][21][22] During this period, he appeared in group shows at the Crocker Art Museum, Real Art Ways and Nasher Museum of Art, among others, and solo exhibitions at Gallery Paule Anglim (now Anglim/Trimble) in San Francisco.[19][20]

By the early-2000s, he had shifted from photochemical methods to a labor-intensive process involving collage, silkscreening and hand-painting that first involved teaching himself to draw in the stylized manner of nineteenth-century wood engraving.[23][1] With this work, he began receiving increased attention, through solo exhibitions at Paule Anglim[24][25] and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects in New York;[26][1] he has continued to exhibit at both galleries.[9][27] In the 2000s, he has also had solo exhibitions at the San Jose Museum of Art, Frist Art Museum, Katzen Arts Center and Kohn Gallery (Los Angeles),[10][28][17][29] and appeared in surveys at the Nevada Museum of Art, de Saisset Museum, San Antonio Museum of Art and Neuberger Museum of Art, among others.[14][30][4][31] A monograph of his work, Dean Byington, was published in 2015 and includes an original short story and poem by Rick Moody and essay by Griff Williams.[10]

Work and reception

Byington's work mainly consists of large canvases fusing screened oil on linen and hand-painting as well as small, detailed works on paper composed of tiny, hand-cut photocopies from old illustrated books and his own drawings.[21] He creates the paintings through a meticulous process merging digital and analog, and the handmade and mechanical.[32][33][8] He photocopies and collages imagery—his drawings, Victorian-era illustrations, historical images—then works into them to achieve coherence, before scanning and silkscreening the work onto canvas (sometimes in multiple prints) and, finally, connecting interstices by hand-painting details and (occasional) washes of color.[2][1][4][34] The canvases function like enclosures, Immersing viewers viscerally in all-over compositions that counterpoint the "antique" quality of the imagery with contemporary painting strategies involving frontality, flatness, layering and instantaneity.[35][2] The work's packed, sometimes-obscured imagery and unexpected juxtapositions—conflicting pictorial and architectural logics, natural and human-made environments devoid of people, animals engaged in human behaviors—generate ambiguous narratives that can range from fanciful, even romantic to eerie to Cassandra-like in their forebodings of apocalypse.[5][18][9][2]

Critics have connected Byington's art to the intricate works of diverse artists including Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Dürer, M. C. Escher and filmmaker Terry Gilliam, the surrealist collages of Max Ernst and Kurt Schwitters, and the mid-20th century Bay Area assemblage and psychedelic aesthetic.[32][36][27][3] In a 2003 essay, John Yau related Byington's use of silkscreening to earlier practitioners such as Rauschenberg and Warhol, but distinguished him—from them and from appropriation artists—by his emphasis on excavating pre-photographic sources rather than recontextualizing contemporary mass-media images.[35][22] In 2017, Griff Williams remarked, "the disjointed labyrinthine structures of Byington's work may be fueled by the legacy of dark scientific experiments or the artifice of Hollywood's past, but they also share sympathy with the Wunderkammer" (or German "cabinets of curiosities"), which "celebrated the intersections between science and superstition, the natural and artificial."[18]

Paintings, 2003–2010

In the 2000s, Byington largely focused on black and white paintings filled edge to edge with detailed renderings of flora, fauna and dilapidated, ramshackle structures, some of them punctuated by washes of jewel-like color (e.g., King and Queen, 2002).[24][7][32] These overgrown scenes were dizzying in their density and perceptually challenging, with flattened spaces lacking traditional entry points or clear distinctions between fore-, middle- and background;[37][32] noting the images' weaving of old and new visual modes, critics simultaneously compared their pattern-like motifs to ornate wallpaper, Chinese scrolls and modernist painting.[7][24][37] The seemingly benign scenes were populated with whimsical, anthropomorphic animals, which upon close inspection, were embroiled in sometimes-savage conflicts that suggested crises and devastations, past and present.[24][1][7] John Yau wrote of such works, "Despite their allusions to the Victorian and Symbolist eras, as well as to children's books, Byington's paintings are hardly nostalgic. In fact, these paintings strike me as both visionary and emotionally attuned to the sense of impending disaster that marks our historical moment."[35]

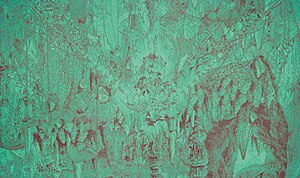

As the decade progressed, Byington pushed the horror vacui sense of density in the work and also began creating color canvasses that suggested mysterious minimalist monochromes in which his signature imagery appeared as if seen through an aquarium or fog (e.g. Underground #1, 2006; Waterfalls 2010);[5][32][27] The New Yorker described them as "glazed in candy-colored pink, green, or robin’s-egg blue, like Easter eggs—or blotter acid."[37] This work included the green "Underground" series, which featured with geologic forms: stalactites, stalagmites, minerals, gems, and cave-like openings into various spaces.[21]

Paintings, 2011–present

Writers suggest that Byington's later paintings explore historical and sociopolitical themes in a more expansive, cinematic manner in terms of vastness (their large scale and God's-eye views), sweeping subjects (climate change, terrorism, urban sprawl) and time (a sense of layer centuries of history including the potential future).[6][2][38] These paintings blur notions of urban and rural, ancient and modern, piling intractable ambiguities and compressed, distressed and fragmentary realities into monumental landscapes, geologic formations and industrial sites suggestive of post-human or post-apocalyptic, possibly alternate civilizations (Omphalos, 2011).[18][29][9][39] SquareCylinder described the maze of cellblock-like huts, scaffolding and brickwork in the black-and-white landscape Divided City (2015) as "an unending public works project … depict[ing] a mismanaged future, an allegory of Big Plans and half-starved dreams."[40]

In his exhibition, "The Theory of Machines" (Kohn Gallery, 2017), Byington presented nine large paintings of desolate, built scenes whose commonalities included skeletal and flayed structures, baroque facades, the great concentric holes of open pit mines and abandoned machines sprawled in ruin (e.g., Theory of Machines (Grand Saturn), 2017).[29][8][36] Bingham Canyon Mine (2017) offered a striated mining-ravaged landscape inspired by photographs of the two largest mines in the world (the title mine, in Utah and the Grasberg mine in Indonesia), "rebuilt into a futuristic city—part Piranesi, part Escher—of interconnected bridges, towers and scaffold-encased structures."[8][2]

Byington's show "Cassandra: Truth and Madness" (Anglim/Trimble, 2022)—its title a reference to the Robinson Jeffers poem, Cassandra—offered a wider range of work depicting the world as a facade teetering on the brink of collapse in the wake of human activity.[9][2] The "Colossus" series (2022) depicted movie sets built on giant scaffolds towering over vast, carved out tracts of land.[9] Draped in front of the vast sites were curtain-like pastoral scenes resembling the romantic paintings of artists such as Frederic Church.[2] The effect was a layering of two human constructs—idealized landscapes embodying Manifest Destiny that obscured the dark side of American expansionism, placed band-aid-like over the giant open pits of mines—a metaphor for the veiling of devastation that political narratives enact.[2] In other paintings, dystopias invaded cinematic interiors; Oceans (2022) depicted a rising tide with a gliding shark swamping an opulent, Victorian bedroom.[2] Hyperallergic's Gabrielle Selz wrote of the show, "Drawing on the blast sites of the Nevada desert and abandoned scenery of movies like Citizen Kane, Byington’s visual language mingles romance and theatricality with the disastrous consequences of climate change and environmental contamination."[2]

Public collections

Byington's work belongs to the public art collections of the Art Institute of Chicago,[12] Berkeley Art Museum,[13] Chazen Museum of Art,[41] Cleveland Clinic,[42] di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art,[43] Fisher Landau Center for Art,[44] Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center,[45] Indianapolis Museum of Art,[46] Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[10] Nevada Museum of Art,[14] San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 21c Museum Hotels,[38] Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,[34] and Whitney Museum of Art,[11] among others.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Sheets, Hilarie M. "Critic's Pick: Dean Byington," ARTnews, January 2006, p. 144

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Selz, Gabrielle. "A Devastating and Breathtaking Vision of Climate Change," Hyperallergic, December 21, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Dambrot, Shana Nys. "Dean Byington: Theory Of Machines at Kohn Gallery," WhiteHot Magazine, June, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Rubin, David. Psychedelic, Optical And Visionary Art Since The 1960s, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Cash, Stephanie. "Dean Byington at Leslie Tonkonow," Art in America, May 2008, p. 199–200.

- ^ a b Davis, Genie. "Dean Byington's The Theory of Machines," Art and Cake, June 16, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Roberta. "Dean Byington," The New York Times, May 6, 2005. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Zellen, Jody. "Kohn Gallery: Dean Byington," Artillery, June 7, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth, David M. "Cassandra Calling," SquareCylinder, December 1, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Moody, Rick, Dean Byington and Griff Williams. Dean Byington, San Francisco: Gallery 16 Editions, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Whitney Museum of American Art. Dean Byington, Artists. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Art Institute of Chicago. Dean Byington, Artists. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Untitled (Fungal Life), Dean Byington, Collection. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Nevada Museum of Art. "Extraction," Exhibitions, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Dalla Villa Adams, Amanda. "Two-Dimensional Exit," Style Weekly (Richmond), January 6, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ayers, Will. "Byington Explores Underworld At The Frist," The Tennessean, June 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Katzen Art Center. "Dean Byington: Buildings without Shadows," American University, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Griff. "Entropy Has No Opposite," in Dean Byington by Dean Byington, Rick Moody and Griff Williams, San Francisco: Gallery 16 Editions, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Yau, John and Gallery Paule Anglim. Dean Byington, San Francisco: Gallery Paule Anglim, 2003. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Raynor, Vivien. "In Hartford, Bumptious and Alive and on the Cutting Edge," The New York Times, November 20, 1994. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ottmann, Klaus. "A Conversation," in Dean Byington: Paintings and Works on Paper, New York: and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Pascale, Mark. "Curator’s Choice: Dean Byington,” F Newsmagazine, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, May 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Baker, Kenneth. "Welcome to Yerba Buena's bargain basement of summer shows," San Francisco Chronicle, July 31, 2003. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Tarshis, Jerome. "Dean Byington at Gallery Paule Anglim," Art in America, December 2003.

- ^ Baker, Kenneth. "Dean Byington at Galerie Paule Anglim," San Francisco Chronicle, February 15, 2003.

- ^ Panero, James. "Gallery Chronicle," The New Criterion, June 2005. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Indrisek, Scott. "Uncharted Territory," Modern Painters, November 2010.

- ^ Frist Art Museum. "Dean Byington: Terra Incognita," Exhibition, 2009. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Haefele, Marc. "Dean Byington's ferocious, unruly impulses in a new show at Kohn Gallery," Off-Ramp, KPCC Public Radio, May 23, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Fischer, Jack. "Conjuring Worlds From Bits and Pieces," San Jose Mercury, May 27, 2003.

- ^ ArtDaily. " Future Tense: Reshaping the Landscape at the Neuberger Museum of Art," June 2, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Falkenberg, Merrill. "Dean Byington," Frieze, April 1, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Roberta. "Art Listings: Dean Byington," The New York Times, June 17, 2005. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Two Harbors, Dean Byington, Collection. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Yau, John. "Invitation to the Labyrinth," Dean Byington, San Francisco: Gallery Paule Anglim, 2003.

- ^ a b Juxtapoz. "Dean Byington's Theory of Machines," April 12, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c The New Yorker. "Dean Byington," November 26, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b 21c Museum Hotels. "Convergence: Highlights from the Collection 2012," Exhibit, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ SquareCylinder. "Best of 2022," December 14, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Couzens, Julia. "Unconscious Rationale @ Anglim Gilbert," SquareCylinder, August 6, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Chazen Museum of Art. The Bees and the Ants, #1, Dean Byington, Collection. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ The Cleveland Clinic. Power of Art: Cleveland Clinic Collection, Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Clinic, 2017, p. 82.

- ^ di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art. Artist List. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ New York Art Beat. "Unforgettable: Selections from the Emily Fisher Landau Collection," Exhibition, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. The Bees and the Ants, #2, Dean Byington, Objects. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Indianapolis Museum of Art. Blue Landscape (Jewels), Dean Byington, Collection. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

External links

- Dean Byington official website

- Dean Byington, Anglim/Trimble

- Dean Byington, Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects