David L. Brainard

David L. Brainard | |

|---|---|

Brainard as a major in 1902 | |

| Birth name | David Legge Brainard |

| Born | December 21, 1856 Norway, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 22, 1946 (aged 89) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Service years | 1876–1919 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Service number | 0-13116 |

| Commands | Chief Commissary, Department of the East Chief Commissary, Department of California Chief Commissary, Philippine Division U.S. Military Attaché, Buenos Aires, Argentina U.S. Military Attaché, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Wars | American Indian Wars Spanish–American War Philippine–American War World War I |

| Awards | Purple Heart Military Order of Christ (Grand Officer) (Portugal) Military Order of Aviz (Grand Officer) (Portugal) Legion of Honor (Officer) (France) |

| Alma mater | State Normal School, Cortland, New York |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Chase (m. 1888–1893, div.) Sara Hall Guthrie Neff (m. 1917–1946, his death) |

David Legge Brainard (December 21, 1856 – March 22, 1946) was a career officer in the United States Army. He enlisted in 1876, received his officer's commission in 1886, and served until 1919. Brainard attained the rank of brigadier general and served during World War I as U.S. military attaché in Lisbon, Portugal.

A native of Norway, New York, Brainard was raised and educated in Norway and nearby Freetown, and graduated from the State Normal School in Cortland, New York.

In addition to his First World War service, Brainard was a veteran of the American Indian Wars, Spanish–American War, and Philippine–American War. He was also a noted arctic explorer who attained fame as one of only six survivors of the 1881 to 1884 Lady Franklin Bay Expedition. He was the recipient of several civilian awards in recognition of his explorations. He died in Washington, D.C., on March 22, 1946, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life

Brainard was born in Norway, New York on December 21, 1856, the fifth son of Alanson Brainard and Maria C. Legge.[1] His family moved to a farm in Freetown, New York, when he was ten years old, and Brainard was raised and educated in Norway and Freetown.[2] He attended the State Normal School in Cortland, New York, and then decided upon a military career.[2][3][4]

Military career

Start of career

Brainard enlisted in the United States Army in September 1876.[2][a][b] He was assigned to the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and served at Fort Keogh, Montana Territory during the Great Sioux War of 1876.[2] On May 7, 1877, Brainard fought in the Battle of Little Muddy Creek, Montana, where he was wounded in the face and right hand.[6] In August 1877, Brainard was one of four soldiers assigned to escort the Army's commanding general, William Tecumseh Sherman and Sherman's party on an inspection tour of Yellowstone National Park.[7] In 1877 and 1878, he served under Nelson Appleton Miles in Montana during the Nez Perce War and Bannock War.[8][9] He was promoted to corporal in October 1877, and sergeant in July 1879.[7]

Arctic exploration

In 1880, he was selected for the Howgate expedition, which started for Greenland in July 1880, but turned back after a heavy storm damaged the expedition's ship.[10] In 1881, he was detailed as first sergeant for the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, which was commanded by Adolphus Greely.[10] Over the three years of this expedition he continuously kept a journal.[11]

Twenty-five men began the expedition, which ran into difficulty when several attempts to resupply it failed, and several rescue attempts were forced to turn back. Among those who died was James Booth Lockwood, second-in-command and Brainard's companion on many excursions, including their record breaking push north to latitude 83° 23' 30". Brainard wrote:

Lieut. Lockwood became unconscious early this morning and at 4:30 pm breathed his last. This will be a sad blow to his family who evidently idolized him. To me it is also a sorrowful event. He had been my companion during long and eventful excursions, and my feeling toward him was akin to that of a brother. Biederbick and myself straightened his limbs and prepared his remains for burial. This was the saddest duty I have ever yet been called upon to perform.[9]

Brainard was later credited with saving as many expedition members as possible by closely rationing the group's limited food.[12] Shortly before the survivors were rescued in the spring of 1884, Brainard, freezing, starving, and suffering from scurvy wrote: "Our own condition is so wretched, so palpably miserable, that death would be welcomed rather than feared ..."[2] Brainard was one of only six survivors rescued by Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley on June 22.[13][c] On that day, he was reportedly near death himself, too weak to hold a pencil so he could make an entry in his log.[9]

Later career

In January 1885, Brainard sought a commission in the 10th Infantry Regiment, but the appointment went to Andre W. Brewster.[14][15] In 1886, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd Cavalry "as recognition of the gallant and meritorious services rendered by him in the Arctic expedition of 1881–1884." He then had the distinction of being the only living US Army officer, active or retired, who had been commissioned as a commendation for specific services.[2]

Brainard was promoted to first lieutenant in August 1893.[10] In October 1896 he transferred to the Subsistence Department and received promotion to captain.[10] In December 1897, he participated in the Yukon Relief Mission, which provided emergency assistance to Klondike Gold Rush miners who were experiencing shortages of food.[10]

In May 1898, Brainard was promoted to temporary lieutenant colonel and he served as chief commissary of the military forces in the Philippines during the Spanish–American War in 1898 and Philippine–American War in 1899.[8] In May 1900, he was promoted to permanent major.[10] His subsequent assignments included chief commissary of the Department of the East, Department of California, and Philippine Division.[16][17] In 1905, Brainard received promotion to permanent lieutenant colonel.[18] Brainard was a charter member of The Explorers Club and served its president from 1912 to 1913.[19] He was promoted to colonel in June 1912.[20]

In 1914, Brainard was assigned as U.S. military attaché in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[21] In October 1917, Brainard received promotion to temporary brigadier general.[22] During World War I, he served as military attaché in Lisbon, Portugal, and he retired as a brigadier general in October 1919.[2]

Family

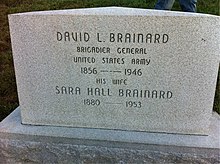

Brainard married Anna Chase in 1888, and they divorced in 1893.[23] In 1917, he married Sara Hall Guthrie (1880–1953).[24] Brainard had no children and was the stepfather of his second wife's daughter Elinor.[8]

Retirement and death

After leaving the Army, Brainard was appointed vice president of the Association of Army and Navy Stores, and was named to the association's board of directors.[5] He remained active in these roles until his death.[5]

He was elected an honorary member of the American Polar Society in 1936, on his 80th birthday.[9][25] He was a Freemason, and belonged to Marathon Lodge No. 438 in Marathon, New York.[26]

Brainard died at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. on March 22, 1946.[27] He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[27] He was the last survivor of the Greely Arctic Expedition.[28]

Awards

Military awards

The Purple Heart medal was created in 1932.[29] On January 27, 1933, Brainard received the award for wounds he sustained at the Battle of Little Muddy Creek on May 7, 1877.[30] His was one of only two Purple Hearts known to have been awarded for the American Indian Wars, because posthumous awards were not authorized and eligible individuals had to proactively submit applications.[31]

In addition to the Purple Heart, Brainard's military awards and decorations included:[32][33]

- Purple Heart

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- Military Order of Christ (Grand Officer) (Portugal)

- Military Order of Aviz (Grand Officer) (Portugal)

- Legion of Honor (Officer) (France)

Civilian awards

In addition to his military awards, Brainard received the Royal Geographical Society's Back Award in 1886.[34] He was a fellow of the American Geographical Society, and his arctic explorations resulted in award of the society's Charles P. Daly Medal in 1926.[35][36] He was also a 1929 recipient of the civilian Explorers Club Medal.[32]

Brainard was also inducted into the Cortland County Hall of Fame.[37] The hall is maintained by the Homeville Museum in Cortland, and recognizes significant county residents in eras from pre-1850 to 1975-current.[37]

Publications

- The Outpost of the Lost. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company. 1929. OCLC 2027965.

- Six Came Back. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company. 1940. OCLC 2168015.

Notes

- ^ According to some sources, Brainard attended the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. He was traveling home and discovered while changing trains in New York City that he did not have enough cash to purchase a ticket for the rest of the journey. Rather than ask his family for money, he took the free Army ferry to the recruiting station on Governors Island and signed an enlistment contract. After enlisting, he discovered the ten dollar bill he had previously placed in his shirt pocket, which would have been more than enough to complete his train ride to Freetown.[2]

- ^ In another version of the enlistment story, Brainard was unable to travel beyond New York City because he had been robbed in Philadelphia.[5]

- ^ Seven men were alive when Schley arrived, but one died soon afterwards.[13]

References

- ^ Davis 1998, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stein, Glenn M. (September–October 2009). "General David L. Brainard: Indian Wars Veteran and Last Survivor of the United States' Lady Franklin Bay Arctic Expedition, 1881–84" (PDF). Journal of the Orders and Medals Society of America. Claymont, DE: Orders and Medals Society of America. p. 16.

- ^ Biographical Encyclopedia of the United States. Chicago, IL: American Biographical Publishing Co. 1901. p. 378 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lanman, Charles (1889). Farthest North: Or, The Life and Explorations of Lieutenant James Booth Lockwood. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 315 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b c "Brig. Gen. David Brainard Dies". The Evening Star. Washington, DC. March 23, 1946. p. 3 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- ^ "A Survivor of the Greely Expedition". The Ancient. Boston, MA: Arthur T. Lovell. May 1914. p. 251 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Lanman, Charles (1885). Farthest North: Or, The Life and Explorations of Lieutenant James Booth Lockwood, of the Greely Arctic Expedition. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 315 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Dartmouth College Library collection of papers and chronology.

- ^ a b c d The Arctic Saga of David Legg Brainard Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Who's Who in New York City and State (First ed.). New York: L. R. Hammersly. 1904. p. 81 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dartmouth College Library. "David Brainard Diary". 2020. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Copley, Frank Barkley (March 1912). "Heroes of the Outdoors: David L. Brainard". The Outing Magazine. Chicago; NY: Outing Publishing Company. pp. 697–699 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Reck, Stephen Noah (2018). "The Greely Sensation: Arctic Exploration and the Press". Scholar Works.UVM.edu. University of Vermont. p. 6. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ "Gen. Brewster, 79, Officer 57 Years". The New York Times. New York. March 28, 1942. p. 17 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ "Condensed News: Domestic; A. W. Brewster". Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, IN. November 27, 1884. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brooke, John R. (1900). Annual Report, Department of the East. Governors Island, NY: Headquarters, Department of the East. p. 3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Army: Subsistence Department". Army and Navy Journal. New York. January 9, 1909. pp. 515–516 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ U.S. Senate (December 6, 1905). "Appointments in the Army: Subsistence Department". Congressional Record. Vol. XL. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 165–166 – via Google Books.

- ^ ECWG_Admin (April 12, 2017). "John Glenn Tribute". Explorers Club Washington Group. Washington, DC.

- ^ "In the Social World: Lieut.-Col. David L. Brainard". The Daily Standard Union. Brooklyn, NY. June 16, 1912. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pan American Notes: Col. David L. Brainard to be Appointed Military Attaché in Buenos Aires". Bulletin of the Pan American Union. Washington, DC: Pan American Union. July 1914. p. 293 – via Google Books.

- ^ "New Brigadier Generals". Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, AR. October 3, 1917. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Urness, James (2014). 25 Brave Men: Tales of an Arctic Journey. Tucson, AZ: Wheatmark. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-1-6278-7039-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Urness, p. 146.

- ^ "Gen. Brainard Honored. Last Survivor of Greely Expedition Enrolled in Polar Society at 80". The New York Times. December 22, 1936. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ Steele, Eric C. (December 21, 2023). "David Legge Brainard Is Born". Today in Masonic History. Masonry Today.com. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "Death Notice, David L. Brainard". The Evening Star. Washington, DC. March 24, 1946. p. 17 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- ^ Davis 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Borch, Fred (2013). For Military Merit: Recipients of the Purple Heart. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-6125-1409-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Borch, p. 28.

- ^ Borch, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Stein, Glenn M. (August 1, 2007). "The Historic and Unique Collection of Medals and Artifacts of General David L. Brainard, USA (1856-1946)" (PDF). Little Big Horn.info. Choctaw Beach, FL: Diane Merkel. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Portuguese Honors Orders". Ordens.Presidencia.pt. Lisbon, Portugal: Presidency of the Portuguese Republic. 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ Year-Book and Record. London, England: Royal Geographic Society. 1902. p. 222 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gates, Merrill E., ed. (1905). Men of Mark in America. Vol. I. Washington, DC: Men of Mark Publishing Company. p. 172 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Numismatist. Vol. 39. Colorado Springs, CO: American Numismatic Association. 1926. p. 62 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Homeville Museum's Cortland County Hall of Fame Nominees" (PDF). Homeville Museum.com. Cortland, New York: Homeville Museum. December 16, 2016. p. 2. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

Bibliography

- Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh: Pentland Press. ISBN 978-1-5719-7088-6.

External links

- Works by David L. Brainard at Open Library

- Works by or about David L. Brainard at the Internet Archive

- The Papers of David L. Brainard at Dartmouth College Library

- Elinor McVickar Correspondence with Ellen R. Brainard at Dartmouth College Library

- "Burial Record, David L. Brainard". Arlington National Cemetery. Arlington, VA: Office of Army Cemeteries. Retrieved August 15, 2021.