Danilo I, Metropolitan of Cetinje

Danilo I | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan of Cetinje | |

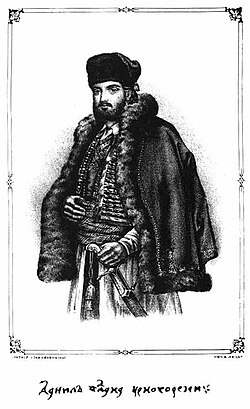

Romanticized illustration from The Mountain Wreath, 1847 | |

| Native name | Данило I |

| Church | Serbian Orthodox Church |

| See | Skenderija and Primorje |

| Elected | 1697 |

| In office | 1697–1735 |

| Predecessor | Savatije |

| Successor | Sava Petrović |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | June 1700 by Arsenije III Crnojević |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1670 |

| Died | 11 January 1735 Podmaine monastery, Republic of Venice |

| Buried | Orlov krš (Eagle's Rock), Cetinje |

| Nationality | Montenegrin |

| Residence | Cetinje |

| Coat of arms |  |

Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian Cyrillic: Данило I Петровић-Његош; 1670 – 11 January 1735) was the Metropolitan of Cetinje between 1697 and 1735, and the founder of the House of Petrović-Njegoš, which ruled Montenegro from 1697 to 1918.

He was also known by the patronymic Danilo Šćepčević.

Early life and background

Danilo Šćepčević[a] was born in Njeguši, the son of Stepan or Šćepan Kaluđerović, a merchant, and Ana, who later became a nun.[1] He had a brother, Radul, known as Rade Šćepčev.[2] His paternal family belonged to the Heraković brotherhood.[3]

As a fifteen-year-old, he was a witness to the battle of Vrtijeljka (1685).[4] It is possible that he heard the details of the battle from some survivor.[4] He mentioned "noble and famous hajduks who fell at Vrtijeljka" in a letter to the Montenegrin chiefs dated to 1714.[4]

After the death of Sava Očinić, the Metropolitan of Cetinje, in 1697, there was turmoil surrounding the election of a new metropolitan.[1]

Chirotony

In 1697, the Montenegrin tribal assembly chose Danilo Šćepčević as the head of the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Cetinje,[1] following the Great Migrations of the Serbs which left the seat of the Serbian Church to Phanariote Greeks who were closely associated with the Porte. Danilo was, as other Serbian bishops, unwilling to subordinate himself to Kalinik I, the new Patriarch of Peć.

In 1700, he chose not to attend an assembly dedicated to Kalinik in Peć, but instead went to Dunaszekcső (Sečuj), in Habsburg Hungary, at the assembly of the Serbian Patriarch in exile, Arsenije III Crnojević.[5] Danilo was chirotonized by Arsenije III Crnojević as the bishop of Cetinje and Metropolitan of Skenderija and Primorje.[6] The chirotony, which took place during the national-church assembly, was participated by Serbian metropolitans from all over the Serbian lands,[7] as well as other notable Serbs. It is likely that Danilo had met Arsenije III earlier when Arsenije was in Cetinje in 1689, asking the Montenegrins to take up arms and unite, to organize a fight against the Ottomans.[6]

Tenure

He coordinated defense operations and partially settled tribal disputes among his people.

An uprising broke out in 1711, after calls by Danilo, where the Montenegrins fought alongside Highlanders and Herzegovinians against local Ottomans.[8]

During his rule political ties between Russia and Montenegro were first established. Russian historian Pavel Rovinsky, in writing about Montenegrin-Russian relations, concluded that it was the pretensions of Turkey and Austria (and at times the Republic of Venice) that turned Montenegro to Russia. Having nowhere to turn in the terrible struggle for the survival of their people, the leading spirits of the Serb land of Montenegro turned to the past, to their mythical origins—to the ancient homeland of the Slavs—all the more readily because it was not only a Great Power but an increasingly powerful factor as a counter-Turkish and counter-Austrian force.

Danilo had this message for the Montenegrin common council (zbor) and its tribal chiefs in 1714:

My death would be graceful if you would want to all unite and perish honourably and gloriously, as was done by Prince Lazar and Miloš Obilić who slew the Sultan on Kosovo, and finally fell with his master and all 7,000 fighters – which led us Montenegrins to this rubble – leaving after themselves glory and honour.[9]

In 1715, Danilo visited Czar Peter I at St. Petersburg and secured his alliance against the Ottomans—a journey that became traditional among his successors in Montenegro and in all the Serbian lands elsewhere in the Balkans. He subsequently recovered Zeta from the Ottomans, restored the monastery at Cetinje, and erected defences around Podostrog-Podmaine Monastery in Budva, which was rebuilt in 1630 and served as a summer residence of the ruling family of Montenegro.

On 1 May 1718 the Republic of Venice recognized Danilo as the spiritual authority over the Orthodox in Paštrovići and the Bay of Kotor.[10] From then on, until the fall of Venice, the Metropolitans of Cetinje had the right to build new and reconstruct destroyed churches in those territories, and to freely preach there.[10]

Succession

Danilo was succeeded by two close kinsmen, first his nephew Sava II Petrović Njegoš and then his nephew Vasilije Petrović Njegoš, who for more than two decades was able to push aside the unworldly Sava and become effectively the highest authority in Montenegro and its representative abroad. Danilo's choice of Sava II clearly had a lot to do with family ties and clan membership, Sava's family came from the Petrovići's native Njeguši. Like Danilo, Sava became a monk, serving in the Maine monastery on the coast where he was consecrated as an archpriest in 1719 by the Serbian Patriarch of Peć, Mojsije (1712–1726). From the time of his ordination onwards, Danilo sought to introduce the young Sava gradually to political life, conferring on him the office of coadjutor in confirmation of his future role. But little about Sava's later career suggests that he gained much from early exposure to Danilo's experience, except that he continued to maintain a policy of status quo while allowing the tribal chieftains a free hand to do as they pleased.

Politics

Danilo was instrumental in the process of connecting families, clans and tribes.[11]

He was said to have issued the "extermination of the Turkicized" (Istraga poturica), as included in The Mountain Wreath (1847), however, there are views that this never happened.

Styles

- "Danil, Metropolitan of Skenderija and Primorje" (Данил, митрополит Скендерије u Приморја), 1715.[12]

- "Danil, Bishop of Cetinje, Njegoš, Duke of the Serb land" (Данил, владика цетињски, Његош, војеводич српској земљи), 1732.[12][13]

Annotations

- ^He is also known in literature and historiography[1] as Danilo Petrović. He was known by the patronymic surname Šćepčev or Šćepčević, while Petrović (Петровић) was used in the family only later;[14] he never called himself Petrović–it was first used by his nephews Sava and Vasilije,[2] after a progenitor of the Petrović-Njegoš, Radul, known by his monastic name Petar,[11] or after their father, Petar.[3] He signed himself Danilo Šćepčev Heraković Njeguš (Данило Шћепчев Хераковић Његуш).[3]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Stamatović 1999.

- ^ a b Ruvarac 1899, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Srpsko Učeno Društvo 1874, pp. 57–.

- ^ a b c Vuković 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti (1904). Glas. Vol. 68, 70, 72. p. 160.

датака, јасно је и зашто млетачки штићеник Данило, изабран за цетињског владику 1696 године, не иде 1700 године на посвећење патријарху Калинику у Пећ него Арсенију III у Сечуј. Што се све ово дешава, нема сумње да у ...

- ^ a b Vuković 1996, p. 21

онда се не треба чудити зашто се овај владика 1700. године запутио у далеки Сечуј да га, управо он — Арсеније III Чарнојевић, његов земљак и комшија, хиротонише за владику цетињ- ског и митрополита Скандарије и Приморја. Вероватно је Данило Шћепчевић, као деветна- естогодишњи младић, упознао Арсенија III Чарноје- вића када је 1689. године боравио у Цетињу, свом родном крају, и можда га је слушао када је ватреним речима подстицао Црногорце да прихвате оружје и у Христово име, са његовим благословом, међусобно уједињени, организују борбу против Мухамедо- вих следбеника, односно када је

- ^ Sava (Bishop of Šumadija.) (1996). Srpski jerarsi: od devetog do dvadesetog veka. Evro. p. 156.

- ^ Vuković 1996, p. 184.

- ^ Батрић Јовановић (1986). Црногорци о себи (од владике Данила до 1941): прилог историји црногорске нације. Народна књ. ISBN 978-86-331-0048-9.

Мила би ми била смрт да сте ви хтјели да сви уједињени изгинемо часни и славно, као што је то учинио сам Кнез Лазар и Милош Обилић који уби цара на Косову, па најзад и сам погибе са својим господаром и свих седам хиљада бораца, - што нас Црногорце довело у ове крше, - оставивши послије себе славу и част.

- ^ a b Rajko L. Veselinović (1966). Istorija srpske pravoslavne crkve sa narodnom istorijom. p. 48.

- ^ a b Milivoje Pajović (2001). Vladari srpskih zemalja. Gramatik.

Унутрашњи развој доводи до чврстог повези- вања родова, братстава и племена, а главни носилац тог процеса био је владика Данило (Шћепчевић) Петровић. Родоначелник Петровића-Његоша био је Радул, у монаштву Петар.

- ^ a b Matica srpska, Lingvistička sekcija (1974). Zbornik za filologiju i lingvistiku, Volume 17, Issues 1-2. Novi Sad: Matica srpska. p. 84.

Данил, митрополит Скендерије u Приморја (1715. г.),28 Данил, владика цетински Његош, војеводич српској земљи (1732. г.).

- ^ Velibor V. Džomić (2006). Pravoslavlje u Crnoj Gori. Svetigora. ISBN 9788676600311.

То се види не само по његовом познатом потпису „Данил Владика Цетињски Његош, војеводич Српској земљи" (Запис 1732. г.) него и из цјелокупког његовог дјелања као митрополита и господара. Занимљиво је у том контексту да ...

- ^ Владимир Ћоровић; Драгољуб С Петровић (2006). Историја Срба. Дом и школа. p. 481. ISBN 9788683751303.

владика Данило Шћепчевић, после прозвао Петровић

Sources

- Luburić, Andrija; Perović, Špiro M. (1940). Porijeklo i prošlost Dinastije Petrovića. Mlada Srbija.

- Medaković, Milorad G. (1997). Marijan Miljić (ed.). Vladika Danilo (in Serbian). Cetinje: Unireks Podgorica.

- Ruvarac, Ilarion (1899). Prilošci istoriji crne gore. Štamparija Jovana Iuljo.

- Stamatović, Aleksandar (1999). "Митрополија црногорска за вријеме митрополита Петровића". Кратка историја Митрополије Црногорско-приморске (1219-1999).

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.

- Srpsko Učeno Društvo (1874). Glasnik Srpskoga Učenog Društva. Vol. 40. pp. 57–.

- Vuković, Novo (1996). Književnost Crne Gore od XII do XIX vijeka. Vol. 11. Obod.

External links

- "Sva svojeručna pisma vladike Danila Petrovića". Montenegrina. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.