Roman Dacia

Roman Dacia

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||||||||

| 106–271/275 | |||||||||||||

Roman province of Dacia (125 AD) | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Annexed by Trajan | 106 | ||||||||||||

• Withdrawal by Roman emperor Aurelian | 271/275 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on |

|

| Dacia |

| Geography |

|---|

| Culture |

| History |

| Roman Dacia |

| Legacy |

Roman Dacia (/ˈdeɪʃə/ DAY-shə; also known as Dacia Traiana (Latin for 'Trajan’s Dacia'); or Dacia Felix, lit. 'Fertile Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (today all in Romania, except the last region which is split among Romania, Hungary, and Serbia). During Roman rule, it was organized as an imperial province on the borders of the empire. It is estimated that the population of Roman Dacia ranged from 650,000 to 1,200,000. It was conquered by Trajan (98–117) after two campaigns that devastated the Dacian Kingdom of Decebalus. However, the Romans did not occupy its entirety; Crișana, Maramureș, and most of Moldavia remained under the Free Dacians.

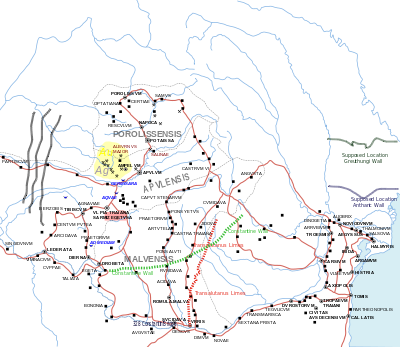

After its integration into the empire, Roman Dacia saw constant administrative division. In 119 under Hadrian, it was divided into two departments: Dacia Superior ("Upper Dacia") and Dacia Inferior ("Lower Dacia"; later named Dacia Malvensis). Between 124 and around 158, Dacia Superior was divided into two provinces, Dacia Apulensis and Dacia Porolissensis. The three provinces would later be unified in 166 and be known as Tres Daciae ("Three Dacias") due to the ongoing Marcomannic Wars. New mines were opened and ore extraction intensified, while agriculture, stock breeding, and commerce flourished in the province. Roman Dacia was of great importance to the military stationed throughout the Balkans and became an urban province, with about ten cities known and all of them originating from old military camps. Eight of these held the highest rank of colonia. Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa was the financial, religious, and legislative center and where the imperial procurator (finance officer) had his seat, while Apulum was Roman Dacia's military center.

From its creation, Roman Dacia suffered great political and military threats. The Free Dacians, allied with the Sarmatians, made constant raids in the province. These were followed by the Carpi (a Dacian tribe) and the newly arrived Germanic tribes (Goths, Taifali, Heruli, and Bastarnae) allied with them. All this made the province difficult for the Roman emperors to maintain, already being virtually lost during the reign of Gallienus (253–268). Aurelian (270–275) would formally relinquish Roman Dacia in 271 or 275 AD. He evacuated his troops and civilian administration from Dacia, and founded Dacia Aureliana with its capital at Serdica in Lower Moesia. The Romanized population still left was abandoned, and its fate after the Roman withdrawal is controversial. According to one theory, the Latin spoken in Dacia, mostly in modern Romania, became the Romanian language, making the Romanians descendants of the Daco-Romans (the Romanized population of Dacia). The opposing theory states that the origin of the Romanians actually lies on the Balkan Peninsula.

Background

The Dacians and the Getae frequently interacted with the Romans prior to Dacia's incorporation into the Roman Empire.[1] However, Roman attention on the area around the lower Danube was sharpened when Burebista[1] (82–44 BC)[2] unified the native tribes and began an aggressive campaign of expansion. His kingdom extended to Pannonia in the west and reached the Black Sea to the east, while to the south his authority extended into the Balkans.[3]

By 74 BC,[3] the Roman legions under Gaius Scribonius Curio reached the lower Danube and proceeded to come into contact with the Dacians.[4] Roman concern over the rising power and influence of Burebista was amplified when he began to play an active part in Roman politics. His last minute decision just before the Battle of Pharsalus to participate in the Roman Republic's civil war by supporting Pompey meant that once the Pompeians were dealt with, Julius Caesar would turn his eye towards Dacia.[5] As part of Caesar's planned Parthian campaign of 44 BC, he prepared to cross into Dacia and eliminate Burebista, thereby hopefully causing the breakup of his kingdom.[6] Although this expedition into Dacia did not happen due to Caesar's assassination, Burebista failed to bring about any true unification of the tribes he ruled. Following a plot which saw him assassinated, his kingdom fractured into four distinct political entities, later becoming five, each ruled by minor kings.[7][8]

From the death of Burebista to the rise of Decebalus, Roman forces continued to clash against the Dacians and the Getae.[1] Constant raiding by the tribes into the adjacent provinces of Moesia and Pannonia caused the local governors and the emperors to undertake a number of punitive actions against the Dacians.[1] All of this kept the Roman Empire and the Dacians in constant social, diplomatic, and political interaction during much of the late pre-Roman period.[1] This saw the occasional granting of favoured status to the Dacians in the manner of being identified as amicii et socii – "friends and allies" – of Rome, although by the time of Octavianus this was tied up with the personal patronage of important Roman individuals.[1] An example of this was seen in Octavianus' actions during his conflict with Marcus Antonius. Seeking to obtain an ally who could threaten Antonius' European provinces, in 35 BC Octavianus offered an alliance with the Dacians, whereby he would marry the daughter of the Dacian King, Cotiso, and in exchange Cotiso would wed Octavianus' daughter, Julia.[9][10]

Although it is believed that the custom of providing royal hostages to the Romans may have commenced sometime during the first half of the 1st century BC, it was certainly occurring by Octavianus' reign and it continued to be practised during the late pre-Roman period.[11] On the flip side, ancient sources have attested to the presence of Roman merchants and artisans in Dacia, while the region also served as a haven for runaway Roman slaves.[11] This cultural and mercantile exchange saw the gradual spread of Roman influence throughout the region, most clearly seen in the area around the Orăștie Mountains.[11]

The arrival of the Flavian dynasty, in particular the accession of the emperor Domitian, saw an escalation in the level of conflict along the lower and middle Danube.[12] In approximately 84 or 85 AD the Dacians, led by King Decebalus, crossed the Danube into Moesia, wreaking havoc and killing the Moesian governor Gaius Oppius Sabinus.[13] Domitian responded by reorganising Moesia into Moesia Inferior and Moesia Superior and launching a war against Decebalus. Unable to finish the war due to troubles on the German frontier, Domitian concluded a treaty with the Dacians that was heavily criticized at the time.[14] This would serve as a precedent to the emperor Trajan's wars of conquest in Dacia.[12] At this time Domitian moved Legio IV Flavia Felix from Burnum to its base at Singidunum (modern Belgrade, Serbia) in Moesia Superior.[15]

Trajan led the Roman legions across the Danube, penetrating Dacia and focusing on the important area around the Orăștie Mountains.[16] In 102,[17] after a series of engagements, negotiations led to a peace settlement where Decebalus agreed to demolish his forts while allowing the presence of a Roman garrison at Sarmizegetusa Regia (Grădiștea Muncelului, Romania) to ensure Dacian compliance with the treaty.[16] Trajan also ordered his engineer, Apollodorus of Damascus,[18] to design and build a bridge across the Danube at Drobeta.[17]

Trajan's second Dacian campaign in 105–106 was very specific in its aim of expansion and conquest.[16] The offensive targeted Sarmizegetusa Regia.[19] The Romans besieged Decebalus' capital, which surrendered and was destroyed.[17] The Dacian king and a handful of his followers withdrew into the mountains, but their resistance was short-lived and Decebalus committed suicide.[20] Other Dacian nobles, however, were either captured or chose to surrender.[21] One of those who surrendered revealed the location of the Dacian royal treasury, which was of enormous value: 500,000 pounds (230,000 kilograms) of gold and 1,000,000 pounds (450,000 kilograms) of silver.[21]

It is an excellent idea of yours to write about the Dacian war. There is no subject which offers such scope and such a wealth of original material, no subject so poetic and almost legendary although its facts are true. You will describe new rivers set flowing over the land, new bridges built across rivers, and camps clinging to sheer precipices; you will tell of a king driven from his capital and finally to death, but courageous to the end; you will record a double triumph one the first over a nation hitherto unconquered, the other a final victory.

Dacia under the Antonine and Severan emperors (106–235)

Establishment (106–117)

Trajan conquered the Dacians, under King Decibalus, and made Dacia, across the Danube in the soil of barbary, a province that in circumference had ten times 100,000 paces; but it was lost under Imperator Gallienus, and, after Romans had been transferred from there by Aurelian, two Dacias were made in the regions of Moesia and Dardania.

With the annexation of Decebalus' kingdom, Dacia was turned into Rome's newest province, only the second such acquisition since the death of Augustus nearly a century before.[24] Decebalus' Sarmatian allies to the north were still present in the area, requiring a number of campaigns that did not cease until 107 at the earliest;[25] however, by the end of 106, the legions began erecting new castra along the frontiers.[26] Trajan returned to Rome in the middle of June 107.[27]

After the conflict the Emperor Trajan proclaimed:

"Alone I have defeated peoples from beyond the Danube and I have annihilated the people of the Dacians."

Roman historian Flavius Eutropius mentioned the fate of Dacians after the Roman victory in the Breviarium Historiae Romanae:

"Trajan, after he had subdued Dacia, had transplanted thither an infinite number of people from the whole Roman world, to people the country and the cities; as the land had been exhausted of inhabitants in the long war maintained by Decebalus."

"The Getae, a barbarian and vigorous people who rising against the Romans and humiliating them such as to compel them to pay a tribute, were later, at the time of king Decebal, destroyed by Trajan in such a way that their entire people was reduced to forty men as Kriton tells in the Getica".

Roman sources list Dacia as an imperial province on 11 August 106.[31] It was governed by an imperial legate of consular standing, supported by two legati legionis who were in charge of each of the two legions stationed in Dacia. The procurator Augusti was responsible for managing the taxation of the province and expenditure by the military.[32]

Transforming Dacia into a province was a very resource-intensive process. Traditional Roman methods were employed, including the creation of urban infrastructure such as Roman baths, forums and temples, the establishment of Roman roads, and the creation of colonies composed of retired soldiers.[33] However, excluding Trajan's attempts to encourage colonists to move into the new province, the imperial government did hardly anything to promote resettlement from existing provinces into Dacia.[33]

An immediate effect of the wars leading to the Roman conquest was a decrease in the population in the province.[34] Crito wrote that approximately 500,000 Dacians were enslaved and deported, a portion of which were transported to Rome to participate in the gladiatorial games (or lusiones) as part of the celebrations to mark the emperor's triumph.[25] To compensate for the depletion of the population, the Romans carried out a program of official colonisation, establishing urban centres made up of both Roman citizens and non-citizens from across the empire.[35] Nevertheless, native Dacians remained at the periphery of the province and in rural settings, while local power elites were encouraged to support the provincial administration, as per traditional Roman colonial practice.[36]

Trajan established the Dacian capital, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, some 40 km (25 mi) west of the ruined Sarmizegetusa Regia.[37] Initially serving as a base for the Legio IV Flavia Felix,[38] it soon was settled by the retired veterans who had served in the Dacian Wars, principally the Fifth (Macedonia), Ninth (Claudia), and Fourteenth (Gemina) legions.[39]

It is generally assumed that Trajan's reign saw the creation of the Roman road network within imperial Dacia, with any pre-existing natural communication lines quickly converted into paved Roman roads[40] which were soon extended into a more extensive road network.[40] However, only two roads have been attested to have been created at Trajan's explicit command: one was an arterial road that linked the military camps at Napoca and Potaissa (modern Cluj-Napoca and Turda, Romania).[40] Epigraphic evidence on the milliarium of Aiton indicates that this stretch of road was finished sometime during 109–110 AD.[41] The second road was a major arterial road that passed through Apulum (modern Alba Iulia, Romania), and stretched from the Black Sea in the east all the way to Pannonia Inferior in the west and presumably beyond.[40] Nevertheless, the arterial roads and other presumably unstable regions were controlled by a vast new network of forts for cohorts and auxiliary units, initially built in turf and wood and many of them later rebuilt in stone. Their garrisons were drawn from many parts of the empire.

| Name | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Julius Sabinus | 105 | 107/109 |

| Decimus Terentius Scaurianus | 109 | 110/111 |

| Gaius Avidius Nigrinus | 112 | 113 |

| Quintus Baebius Macer | 114 | 114 |

| Gaius Julius Quadratus Bassus | ? | 117 |

First re-organisations (117–138)

Hadrian was at Antioch in Syria when word came through of the death of Trajan.[43] He could not return to Rome, as he was advised that Quadratus Bassus, ordered by Trajan to protect the new Dacian territories north of the Danube, had died there while on campaign.[44] As a result of taking several legions and numerous auxiliary regiments with him to Parthia, Trajan had left Dacia and the remaining Danubian provinces below strength.[45][46] The Roxolani allied themselves with the Iazyges to revolt against Rome, as they were angry over a Roman decision to cease payments to which Trajan had agreed.[47] Therefore, Hadrian dispatched the armies from the east ahead of him, and departed Syria as soon as he was able.[46]

By this time, Hadrian had grown so frustrated with the continual problems in the territories north of the Danube that he contemplated withdrawing from Dacia.[48] As an emergency measure, Hadrian dismantled Apollodorus' bridge across the Danube, concerned about the threat posed by barbarian incursions across the Olt River and a southward push.[46]

By 118, Hadrian himself had taken to the field against the Roxolani and the Iazyges, and although he defeated them, he agreed to reinstate the subsidies to the Roxolani.[47][49] Hadrian then decided to abandon certain portions of Trajan's Dacian conquests. Most of the Banat was conceded to the Iazyges. The territories annexed to Moesia Inferior (Southern Moldavia, the south-eastern edge of the Carpathian Mountains and the plains of Muntenia and Oltenia) were returned to the Roxolani.[50][49][51] As a result, Moesia Inferior reverted once again to the original boundaries it possessed prior to the acquisition of Dacia.[52] The portions of Moesia Inferior to the north of the Danube were split off and refashioned into a new province called Dacia Inferior.[52] Trajan's original province of Dacia was relabelled Dacia Superior.[52] Hadrian moved the detachment of Legio IV Flavia Felix that had been at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa back to its base at Singidunum.[53]

The Limes Alutanus was established as the eastern frontier of Dacia Superior.

By 124, an additional province called Dacia Porolissensis was created in the northern portion of Dacia Superior,[54] roughly located in north-western Transylvania.[52] Since it had become tradition since the time of Augustus that former consuls could only govern provinces as imperial legates where more than one legion was present, Dacia Superior was administered by a senator of praetorian rank.[54] This meant that the imperial legate of Dacia Superior only had one legion under his command, stationed at Apulum.[32] Dacia Inferior and Dacia Porolissensis were under the command of praesidial procurators of ducenary rank.[32]

Hadrian vigorously exploited the opportunities for mining in the new province.[55] The emperors monopolized the revenue generated from mining by leasing the operations of the mines to members of the Equestrian order, who employed a large number of individuals to manage the operations.[56] In 124, the emperor visited Napoca and made the city a municipium.[57]

Consolidation (138–161)

The accession of Antoninus Pius saw the arrival of an emperor who took a cautious approach to the defense of some provinces.[58] The large amount of milestones dated to his reign demonstrates that he was particularly concerned with ensuring that the roads were in a constant state of repair.[59] Stamped tiles show that the amphitheatre at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, which had been built during the earliest years of the colonia, was repaired under his rule.[60] In addition, given the exposed position of the larger of the Roman fortifications at Porolissum (near Moigrad, Romania), the camp was reconstructed using stone, and given sturdier walls for defensive purposes.[61]

Following a revolt around 158, Antoninus Pius undertook another reorganisation of the Dacian provinces.[61] Dacia Superior was renamed Dacia Apulensis (in Banat and southern Transylvania), with Apulum as its capital,[61] while Dacia Inferior was transformed into Dacia Malvensis (situated at Oltenia). Romula was its capital (modern Reșca Dobrosloveni, Romania).[62] As per Hadrian's earlier reorganisation, each zone was governed by equestrian procurators, and all were responsible to the senatorial governor in Apulensis.[61]

Marcomannic Wars and their effects (161–193)

Soon after the accession of Marcus Aurelius in 161 AD, it was clear that trouble was brewing along Rome's northern frontiers, as local tribes began to be pressured by migrating tribes to their north.[63][64] By 166 AD, Marcus had reorganized Dacia once again, merging the three Dacian provinces into one called Tres Daciae ("Three Dacias"),[65] a move that was geared to consolidate an exposed province inhabited by numerous tribes in the face of increasing threats along the Danubian frontier.[66] As the province now contained two legions (Legio XIII Gemina at Apulum was joined by Legio V Macedonica, stationed at Potaissa), the imperial legate had to be of consular rank, with Marcus apparently assigning Sextus Calpurnius Agricola.[65] The reorganization saw the existing praesidial procurators of Dacia Porolissensis and Dacia Malvensis continue in office, and added to their ranks was a third procurator for Dacia Apulensis, all operating under the direct supervision of the consular legate,[67] who was stationed at the new provincial capital at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.[68]

Dacia, with its northern, eastern, and western frontiers exposed to attacks, could not easily be defended. When barbarian incursions resumed during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the defences in Dacia were hard pressed to halt all of the raids, leaving exposed the provinces of Upper and Lower Moesia.[69] Throughout 166 and 167 AD, barbarian tribes (the Quadi and Marcomanni)[70] began to pour across the Danube into Pannonia, Noricum, Raetia, and drove through Dacia before bursting into Moesia.[71] A conflict would spark in northern Dacia after 167[72] when the Iazyges, having been thrust out of Pannonia, focused their energies on Dacia and took the gold mines at Alburnus Maior (modern Roșia Montană, Romania).[73] The last date found on the wax tablets discovered in the mineshafts there (which had been hidden when an enemy attack seemed imminent) is 29 May 167.[72] The suburban villas at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa were burned, and the camp at Slăveni was destroyed by the Marcomanni.[49] By the time Marcus Aurelius reached Aquileia in 168 AD, the Iazyges had taken over 100,000 Roman captives and destroyed several Roman castra, including the fort at Tibiscum (modern Jupa in Romania).[74][75]

Fighting continued in Dacia over the next two years, and by 169, the governor of the province Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, was forced to give up his command – it is suspected that he either contracted the plague or died in battle.[76] The emperor decided to temporarily split the province once again between the three sub-provinces, with the imperial legate of Moesia Superior, Marcus Claudius Fronto, taking on the governorship of the central sub-province of Dacia Apulensis.[76] Dacia Malvensis was possibly assigned to its procurator, Macrinius Avitus, who defeated the Langobardi and Obii. The future emperor Pertinax was also a procurator in Dacia during this time, although his exact role is not known. Very unpopular in Dacia, Pertinax was eventually dismissed.[76] By 170, Marcus Aurelius appointed Marcus Claudius Fronto as the governor of the entire Dacian province.[76] Later that year, Fronto's command was extended to include the governorship of Moesia Superior once again.[77] He did not keep it for long; by the end of 170, Fronto was defeated and killed in battle against the Iazyges.[77][78] His replacement as governor of Dacia was Sextus Cornelius Clemens.[77]

That same year (170) the Costoboci (whose lands were to the north or northeast of Dacia)[79] swept through Dacia on their way south.[80] The now weakened empire could not prevent the movement of tribespeople into an exposed Dacia during 171,[81] and Marcus Aurelius was forced to enter into diplomatic negotiations in an attempt to break up some of the barbarian alliances.[81] In 171, the Astingi invaded Dacia; after initially defeating the Costoboci, they continued their attacks on the province.[82] The Romans negotiated a settlement with the Astingi, whereby they agreed to leave Dacia and settle in the lands of the Costoboci.[82] In the meantime, plots of land were distributed to some 12,000 dispossessed and wandering tribespeople, in an attempt to prevent them from becoming a threat to the province if they continued to roam at the edges of Dacia.[83]

The Astingi, led by their chieftains Raüs and Raptus, came into Dacia with their entire households, hoping to secure both money and land in return for their alliance. But failing of their purpose, they left their wives and children under the protection of Clemens, until they should acquire the land of the Costoboci by their arms; but upon conquering that people, they proceeded to injure Dacia no less than before. The Lacringi, fearing that Clemens in his dread of them might lead these newcomers into the land which they themselves were inhabiting, attacked them while off their guard and won a decisive victory. As a result, the Astingi committed no further acts of hostility against the Romans, but in response to urgent supplications addressed to Marcus they received from him both money and the privilege of asking for land in case they should inflict some injury upon those who were then fighting against him.

Throughout this period, the tribes bordering Dacia to the east, such as the Roxolani, did not participate in the mass invasions of the empire.[78] Traditionally seen as a vindication of Trajan's decision to create the province of Dacia as a wedge between the western and eastern Danubian tribes,[78][86] Dacia's exposed position meant that the Romans had a greater reliance on the use of "client-states" to ensure its protection from invasion.[86] While this worked in the case of the Roxolani, the use of the Roman-client relationships that allowed the Romans to pit one supported tribe against another facilitated the conditions that created the larger tribal federations that emerged with the Quadi and the Marcomanni.[87]

By 173 AD, the Marcomanni had been defeated;[88] however, the war with the Iazyges and Quadi continued, as Roman strongholds along the Tisza and Danube rivers were attacked by the Iazyges, followed by a battle in Pannonia in which the Iazyges were defeated.[89] Consequently, Marcus Aurelius turned his full attention against the Iazyges and Quadi. He crushed the Quadi in 174 AD, defeating them in battle on the frozen Danube river, after which they sued for peace.[90] The emperor then turned his attention to the Iazyges; after defeating them and throwing them out of Dacia, the Senate awarded him the title of Sarmaticus Maximus in 175 AD.[78] Conscious of the need to create a permanent solution to the problems on the empire's northern frontiers,[78] Marcus Aurelius relaxed some of his restrictions on the Marcomanni and the Iazyges. In particular, he allowed the Iazyges to travel through imperial Dacia to trade with the Roxolani, so long as they had the governor's approval.[91] At the same time he was determined to implement a plan to annex the territories of the Marcomanni and the Iazyges as new provinces, only to be derailed by the revolt of Avidius Cassius.[78][92]

With the emperor urgently needed elsewhere, Rome once again re-established its system of alliances with the bordering tribes along the empire's northern frontier.[93][94] However, pressure was soon exerted again with the advent of Germanic peoples who started to settle on Dacia's northern borders, leading to the resumption of the northern war.[93][95] In 178, Marcus Aurelius probably appointed Pertinax as governor of Dacia,[96] and by 179 AD, the emperor was once again north of the Danube, campaigning against the Quadi and the Buri. Victorious, the emperor was on the verge of converting a large territory to the north-west of Dacia into Roman provinces when he died in 180.[97][98] Marcus was succeeded by his son, Commodus, who had accompanied him. The young man quickly concluded a peace with the warring tribes before returning to Rome.[93]

Commodus granted peace to the Buri when they sent envoys. Previously he had declined to do so, in spite of their frequent requests, because they were strong, and because it was not peace that they wanted, but the securing of a respite to enable them to make further preparations; but now that they were exhausted he made peace with them, receiving hostages and getting back many captives from the Buri themselves as well as 15,000 from the others, and he compelled the others to take an oath that they would never dwell in nor use for pasturage a 5-mile strip of their territory next to Dacia. The same Sabinianus also, when twelve thousand of the neighboring Dacians had been driven out of their own country and were on the point of aiding the others, dissuaded them from their purpose, promising them that some land in our Dacia should be given them.

Conflict continued in Dacia during the reign of Commodus. The notoriously unreliable Historia Augusta mentions a limited insurrection that erupted in Dacia approximately 185 AD.[93] The same source also wrote of a defeat of the Dacian tribes who lived outside the province.[93] Commodus' legates devastated a territory some 8 km (5.0 mi) deep along the north of the castrum at modern day Gilău to establish a buffer in the hope of preventing further barbarian incursions.[101]

The Moors and the Dacians were conquered during his reign, and peace was established in the Pannonias, but all by his legates, since such was the manner of his life. The provincials in Britain, Dacia, and Germany attempted to cast off his yoke, but all these attempts were put down by his generals.

— Historia Augusta – The Life of Commodus[102]

Revival under the Severans (193–235)

The reign of Septimius Severus saw a measure of peace descend upon the province, with no foreign attacks recorded. Damage inflicted on the military camps during the extensive period of warfare of the preceding reigns was repaired.[103] Severus extended the province's eastern frontier some 14 km (8.7 mi) east of the Olt River, and completed the Limes Transalutanus. The work included the construction of 14 fortified camps spread over a distance of approximately 225 km (140 mi), stretching from the castra of Poiana (situated near the Danube River, in modern Flămânda, Romania) in the south to Cumidava (modern day Brețcu in Romania).[104] His reign saw an increase in the number of Roman municipia across the province,[105] while Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Apulum acquired the ius Italicum.[106]

As part of his military reforms, Severus allowed Roman soldiers to live away from the fortified camps, within the accompanying canabae, where they were allowed to tend nearby plots of land.[107] He also permitted the soldiers to marry local women; consequently, if the soldier was a Roman citizen, his children inherited his citizenship. For those soldiers who were not Roman citizens, both he and his children were granted citizenship upon his discharge from the army.[107]

The next emperor, Caracalla, in order to increase tax revenue and boost his popularity (at least according to the historian Cassius Dio), extended the citizenship to all males throughout the empire, with the exception of slaves.[108] In 213, on his way to the east to begin his Parthian campaign, Caracalla passed through Dacia. While there, he undertook diplomatic maneuvers to disturb the alliances between a number of tribes, in particular the Marcomanni and the Quadi.[109][110] At Porolissum he had Gaiobomarus, the king of the Quadi, killed under the pretext of conducting peace negotiations.[111] There may have been military conflict with one or more of the Danubian tribes.[109][110] Although there are inscriptions that indicate that during Caracalla's visit there was some repair or reconstruction work undertaken at Porolissum[112] and that the military unit stationed there, Cohors V Lingonum, erected an equestrian statue of the emperor,[113] certain modern authors, such as Philip Parker and Ion Grumeza, claim that Caracalla continued to extend the Limes Transalutanus as well as add further territory to Dacia by pushing the border around 50 km (31 mi) east of the Olt River,[114][115] though it is unclear what evidence they are using to support these statements, and the timeframes associated with Caracalla's movements do not support any extensive reorganization in the province.[note 1][116] In 218, Caracalla's successor, Macrinus, returned a number of non-Romanized Dacian hostages whom Caracalla had taken, possibly as a result of some unrest caused by the tribes after Caracalla's assassination.[117]

And the Dacians, after ravaging portions of Dacia and showing an eagerness for further war, now desisted, when they got back the hostages that Caracallus, under the name of an alliance, had taken from them.

There are few epigraphs extant in Dacia dating from the reign of Alexander Severus, the final Severan emperor.[103] Under his reign, the Council of Three Dacias met at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, and the gates, towers, and praetorium of Ad Mediam (Mehadia, Romania) camp were restored.[120]

Life in Roman Dacia

Native Dacians

Evidence concerning the continued existence of a native Dacian population within Roman Dacia is not as apparent as that of Germans, Celts, Thracians, or Illyrians in other provinces.[121] There is relatively poor documentation surrounding the existence of native or indigenous Dacians in the Roman towns that were established after Dacia's incorporation into the empire.[122]

Although Eutropius,[123] supported by minor references in the works of Cassius Dio[124] and Julian the Apostate,[125][126] describes the widespread depopulation of the province after the siege of Sarmizegetusa Regia and the suicide of king Decebalus,[52] there are issues with this interpretation. The remaining manuscripts of Eutropius' Breviarium ab urbe condita, which is the principal source for the depopulation of Roman Dacia after the conquest, are not consistent. Some versions describe the depletion of men after the war; other variants describe the depletion of things, or possibly resources, after Trajan's conquest.[36]

There are such interpretations of archaeological evidence which shows the continuation of traditional Dacian burial practices; ceramic manufacturing continued throughout the Roman period, in both the province as well as the periphery where Roman control was non-existent.[36] Differing interpretations can be made from the final scene on Trajan's Column, which either depicts a Dacian emigration, accelerating the depopulation of Dacia,[127] or Dacians going back to their settlements after yielding to Roman authority.[128]

While it is certain that colonists in large numbers were imported from all over the empire to settle in Roman Dacia,[36] this appears to be true for the newly created Roman towns only. The lack of epigraphic evidence for native Dacian names in the towns suggests an urban–rural split between Roman multi-ethnic urban centres and the native Dacian rural population.[36]

On at least two occasions the Dacians rebelled against Roman authority: first in 117 AD, after Trajan's death,[129] and in 158 AD when they were put down by Marcus Statius Priscus.[130]

The archaeological evidence from various types of settlements, especially in the Oraștie Mountains, demonstrates the deliberate destruction of hill forts during the annexation of Dacia, but this does not rule out a continuity of occupation once the traumas of the initial conquest had passed.[131] Hamlets containing traditional Dacian architecture, such as Obreja and Noșlac, have been dated to the 2nd century AD, implying that they arose at the same time as the Roman urban centres.[131]

Some settlements do show a clear continuity of occupation from pre-Roman times into the provincial period, such as Cetea and Cicău.[132] Archaeological evidence taken from pottery show a continued occupation of native Dacians in these and other areas. Architectural forms native to pre-Roman Dacia, such as the traditional sunken houses and storage pits, remained during Roman times. Such housing continued to be erected well into the Roman period, even in settlements which clearly show an establishment after the Roman annexation, such as Obreja.[133] Altogether, approximately 46 sites have been noted as existing on a spot in both the La Tène and Roman periods.[133]

Where archaeology attests to a continuing Dacian presence, it also shows a simultaneous process of Romanization.[128] Traditional Dacian pottery has been uncovered in Dacian settlements, together with Roman-manufactured pottery incorporating local designs.[128] The increasing Romanization of Dacia meant that only a small number of earlier Dacian pottery styles were retained unchanged, such as pots and the low thick-walled drinking mug that has been termed the "Dacian cup". These artifacts were usually handmade; the use of the pottery wheel was rare.[134] In the case of homes, the use of old Dacian techniques persisted, as did the sorts of ornaments and tools used prior to the establishment of Roman Dacia.[128] Archaeological evidence from burial sites has demonstrated that the native population of Dacia was far too large to have been driven away or wiped out in any meaningful sense.[128] It was beyond the resources of the Romans to have eliminated the great majority of the rural population in an area measuring some 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi).[36] Silver jewellery uncovered in graves show that some of the burial sites are not necessarily native Dacian in origin, but are equally likely to have belonged to the Carpi or Free Dacians who are thought to have moved into Dacia sometime before 200 AD.[135]

Some scholars have used the lack of civitates peregrinae in Roman Dacia, where indigenous peoples were organised into native townships, as evidence for the Roman depopulation of Dacia.[136] Prior to its incorporation into the empire, Dacia was a kingdom ruled by one king, and did not possess a regional tribal structure that could easily be turned into the Roman civitas system as used successfully in other provinces of the empire.[137] Dacian tribes mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography may represent indigenous administrative structures, similar to those from Moesia, Pannonia, Dalmatia, or Noricum.[138]

Few local Dacians were interested in the use of epigraphs, which were a central part of Roman cultural expression. In Dacia this causes a problem because the survival of epigraphs into modern times is one of the ways scholars develop an understanding of the cultural and social situation within a Roman province.[139][140] Apart from members of the Dacian elite and those who wished to attain improved social and economic positions, who largely adopted Roman names and manners, the majority of native Dacians retained their names and their cultural distinctiveness even with the increasing embrace of Roman cultural norms which followed their incorporation into the Roman Empire.[141][142][143]

As per usual Roman practice, Dacian males were recruited into auxiliary units[144] and dispatched across the empire, from the eastern provinces to Britannia.[34] The Vexillation Dacorum Parthica accompanied the emperor Septimius Severus during his Parthian expedition,[145] while the cohort I Ulpia Dacorum was posted to Cappadocia.[146] Others included the II Aurelia Dacorum in Pannonia Superior, the cohort I Aelia Dacorum in Roman Britain, and the II Augusta Dacorum milliaria in Moesia Inferior.[146] There are a number of preserved relics originating from cohort I Aelia Dacorum, with one inscription describing the sica, a distinctive Dacian weapon.[147] In inscriptions the Dacian soldiers are described as natione Dacus. These could refer to individuals who were native Dacians, Romanized Dacians, colonists who had moved to Dacia, or their descendants.[148] Numerous Roman military diplomas issued for Dacian soldiers discovered after 1990 indicate that veterans preferred to return to their place of origin;[149] per usual Roman practice, these veterans were given Roman citizenship upon their discharge.[150]

Colonists

There were varying degrees of Romanization throughout Roman Dacia. The most Romanized segment was the region along the Danube, which was predominately under imperial administration, albeit in a form that was partially barbarized. The population beyond this zone, having lived with the Roman legions before their withdrawal, was substantially Romanized. The final zone, consisting of the northern portions of Maramureș, Crișana, and Moldavia, stood at the edges of Roman Dacia. Although its people did not have Roman legions stationed among them, they were still nominally under the control of Rome, politically, socially, and economically. These were the areas in which resided the Carpi, often referred to as "Free Dacians".[151]

In an attempt to fill the cities, cultivate the fields, and mine the ore, a large-scale attempt at colonization took place with colonists coming in "from all over the Roman world".[152] The colonists were a heterogeneous mix:[35] of the some 3,000 names preserved in inscriptions found by the 1990s, 74% (c. 2,200) were Latin, 14% (c. 420) were Greek, 4% (c. 120) were Illyrian, 2.3% (c. 70) were Celtic, 2% (c. 60) were Thraco-Dacian, and another 2% (c. 60) were Semites from Syria.[153] Regardless of their place of origin, the settlers and colonists were a physical manifestation of Roman civilisation and imperial culture, bringing with them the most effective Romanizing mechanism: the use of Latin as the new lingua franca.[35]

The first settlement at Sarmizegetusa was made up of Roman citizens who had retired from their legions.[154] Based upon the location of names scattered throughout the province, it has been argued that, although places of origin are hardly ever noted in epigraphs, a large percentage of colonists originated from Noricum and western Pannonia.[155]

Specialist miners (the Pirusti tribesmen)[156] were brought in from Dalmatia.[56] These Dalmatian miners were kept in sheltered communities (Vicus Pirustarum) and were under the jurisdiction of their own tribal leadership (with individual leaders referred to as princeps).[156]

Roman army in Dacia

An estimated number of 50,000 troops were stationed in Dacia at its height.[157][53] At the close of Trajan's first campaign in Dacia in 102, he stationed one legion, or a vexillation, at Sarmizegetusa Regia.[53] With the conclusion of Trajan's conquest of Dacia, he stationed at least two legions in the new province: the Legio IV Flavia Felix positioned at Berzobis (modern Berzovia, Romania), and the Legio XIII Gemina stationed at Apulum.[53] It has been conjectured that there was a third legion stationed in Dacia at the same time, the Legio I Adiutrix. However, there is no evidence to indicate when or where it was stationed, and it is unclear whether the legion was fully present, or whether it was only the vexillationes who were stationed in the province.[53]

Hadrian, the subsequent emperor, shifted the fourth legion (Legio IV Flavia Felix) from Berzobis to Singidunum in Moesia Superior, suggesting that Hadrian believed the presence of one legion in Dacia would be sufficient to ensure the security of the province.[53] The Marcomannic Wars that erupted north of the Danube forced Marcus Aurelius to reverse this policy, permanently transferring the Legio V Macedonica from Troesmis (modern Turcoaia in Romania)[158] in Moesia Inferior to Potaissa in Dacia.[53]

Epigraphic evidence attests to large numbers of auxiliary units stationed throughout the Dacian provinces during the Roman period; this has given the impression that Roman Dacia was a strongly militarized province.[53] Yet, it seems to have been no more highly militarized than any of the other frontier provinces, like the Moesias, the Pannonias, and Syria, and the number of legions stationed in Moesia and Pannonia were not diminished after the creation of Dacia.[159][160] However, once Dacia was incorporated into the empire and the frontier was extended northward, the central portion of the Danube frontier between Novae (near modern Svishtov, Bulgaria) and Durostorum (modern Silistra, Bulgaria) was able to release much-needed troops to bolster Dacia's defences.[161] Military documents report at least 58 auxiliary units, most transferred into Dacia from the flanking Moesian and Pannonian provinces, with a wide variety of forms and functions, including numeri, cohortes milliariae, quingenariae, and alae.[53] This does not imply that all were positioned in Dacia at the same time, nor that they were in place throughout the existence of Roman Dacia.[53]

Settlements

When considering provincial settlement patterns, the Romanized parts of Dacia were composed of urban satus settlements, made up of coloniae, municipia, and rural settlements, principally villas with their associated latifundia and villages (vici).[162] The two principal towns of Roman Dacia, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Apulum, are on par with similar towns across the Western Roman Empire in terms of socio-economic and architectural maturity.[163]

The province had about 10 Roman towns,[164][165] all originating from the military camps that Trajan constructed during his campaigns.[166] There were two sorts of urban settlements. Of principal importance were the coloniae, whose free-born inhabitants were almost exclusively Roman citizens. Of secondary importance were the municipia, which were allowed a measure of judicial and administrative independence.[167]

- Towns in Dacia Superior

- Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa was established by Trajan, was first to be given colonia status, and was the province's only colonia deducta.[168] Its pre-eminence was guaranteed by its foundation charter and by its role as the administrative centre of the province, as well as its being granted Ius Italicum.[169]

- Ulpianum

- Singidava

- Germisara

- Argidava

- Bersovia

- Alburnus major

- Apulum (predecessor of Alba Iulia) began as one of Trajan's legionary bases.[168] Almost immediately, the associated canabae legionis was established nearby, while at some point during the Trajanic period a civilian settlement sprang into existence along the Mureș River, approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) from the military encampment.[169] The town evolved rapidly, transforming from a vicus of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa into a municipium during Marcus Aurelius' reign, with the emperor Commodus elevating it to a colonia.[170] Transformed into the capital of Dacia Apulensis region within Dacia Superior, its importance lay in being the location of the military high command for the tripartite province.[62] It began to rival Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa during the reign of Septimius Severus, who allocated a part of Apulum's canabae with municipal status.[170]

- Napoca was the possible location of the military high command in Dacia Porolissensis.[171] It was made a municipium by Hadrian, and Commodus transformed it into a colonia.[158]

- Potaissa was the camp of the Legio V Macedonica during the Marcomannic Wars.[171] Potaissa saw a canabae established at the gates of the camp.[158] Granted municipium status by Septimius Severus, it became a colonia under Caracalla.[158]

The reconstructed gateway of the castrum in Porolissum - Porolissum was situated between two camps, and laid alongside a walled frontier defending the main passageway through the Carpathian Mountains. It was transformed into a municipium during Septimius Severus' reign.[172] Within Dacia Superior, Porolissum was a center of Dacia Prolissensis as Apulum for Dacia Apulensis.

- Dierna/Tierna (modern Orșova, Romania)

- Tibiscum (Jupa, Romania)

- Ampelum (Zlatna, Romania) were important Roman towns.[173] Although the biggest mining town in the region, Ampelum's legal status is unknown.[174] Dierna was a customs station which was granted municipium status by Septimus Severus.[175]

- Sucidava (modern Corabia, Romania) was a town located at the site of an earthwork camp. Erected by Trajan, Sucidava was neither large enough nor important enough to be granted municipium or colonia status. The town remained a pagus or perhaps a vicus.[175]

- Towns in Dacia Inferior

- Drobeta was the most important town of Dacia Inferior. Springing up in the vicinity of a stone camp housing 500 soldiers and established by Trajan to guard the northern approaches to Trajan's Bridge across Ister (The Danube), the town was elevated by the emperor Hadrian to a municipium, holding the same rights as an Italian town.[176] During the middle 190s, Septimius Severus transformed the town into a full-fledged colonia.[177]

- Romula was possibly the capital of Dacia Malvensis. It held the rank of municipium, possibly under the reign of Hadrian, before being elevated to colonia status by Septimius Severus.[178]

It is often problematic to identify the dividing line between "Romanized" villages and those sites that can be defined as "small towns".[179] Therefore, categorizing sites as small towns has largely focused on identifying sites that had some evidence of industry and trade, and not simply a basic agricultural economic unit that would almost exclusively produce goods for its own existence.[180] Additional settlements along the principal route within Roman Dacia are mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana. These include Brucla, Blandiana, Germisara, Petris, and Aquae.[181] Both Germisara and Aquae were sites where natural thermal springs were accessible, and each are still functioning today.[182] The locations of Brucla, Blandiana, and Petris are not known for certain.[182] In the case of Petris however, there is good reason to suppose it was located at Uroi in Romania. If this were the case, it would have been a crucial site for trade, as well as being a vital component in facilitating communication from one part of the province to another.[183]

It is assumed that Roman Dacia possessed a large number of military vici, settlements with connections to the entrenched military camps.[183] This hypothesis has not been tested, as few such sites have been surveyed in any detail. However, in the mid-Mureș valley, associated civilian communities have been uncovered next to the auxiliary camps at Orăștioara de Sus, Cigmău, Salinae (modern Ocna Mureș), and Micia,[183] with a small amphitheatre being discovered at the latter one.[60]

During the period of Roman occupation, the pattern of settlement in the Mureș valley demonstrates a continual shift towards nucleated settlements when compared to the pre-Roman Iron Age settlement pattern.[184] In central Dacia, somewhere between 10 and 28 villages have been identified as aggregated settlements whose primary function was agricultural.[185] The settlement layouts broadly fall between two principal types.[185] The first are those constructed in a traditional fashion, such as Rădești, Vințu de Jos, and Obreja. These show generally sunken houses in the Dacian manner, with some dwellings having evolved to becoming surface timber buildings. The second settlement layout followed Roman settlement patterns.[185]

The identification of villa sites within central Dacia is incomplete, as it is for the majority of the province.[186] There are about 30 sites identified throughout the province which appear on published heritage lists, but this is felt to be a gross underestimation.[186]

Economy

Dacia required great expense for its military garrisons but the mineral deposits in Transylvania must have enhanced Dacia's economic importance to Rome[104] and the most valuable resource was gold.[187] Alburnus Maior was founded by the Romans during the reign of Trajan as a mining town, with Illyrian colonists from South Dalmatia.[188] New information surfaced in the form of wax-coated wooden writing tablets, several of which were discovered at Verespatak from 1786 and which bear a variety of commercial texts, contracts, and accounts dating to 131–167. The earliest reference to the town is on a wax tablet dated 6 February 131.[189] Over time the mines began to see diminishing returns as the local gold reserves were exploited.[56] Evidence points to the closure of the gold mines around the year 215 AD.[175]

With the Roman army ensuring the maintenance of the Pax Romana, Roman Dacia prospered until the Crisis of the Third Century. Dacia evolved from a simple rural society and economy to one of material advancement comparable to other Roman provinces.[157] There were more coins in circulation in Roman Dacia than in the adjacent provinces.[190]

The region's natural resources generated considerable wealth for the empire, becoming one of the major producers of grain, particularly wheat.[128] Linking into Rome's monetary economy, bronze Roman coinage was eventually produced in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa[164] by about 250 AD (previously Dacia seems to have been supplied with coins from central mints).[190] The establishment of Roman roads throughout the province facilitated economic growth.[164]

Dacia also possessed salt, iron, silver, and copper mines dating to the period of the Dacian kings.[128] The region also held large quantities of building-stone materials, including schist, sandstone, andesite, limestone, and marble.[56]

Towns became key centres of manufacturing.[191] Bronze casting foundries existed at Porolissum, Romula, and Dierna; there was a brooch workshop located in Napoca, while weapon smithies have been identified in Apulum.[191] Glass manufacturing factories have been uncovered in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Tibiscum.[191] Villages and rural settlements continued to specialise in craftwork, including pottery, and sites such as Micăsasa could possess 26 kilns and hundreds of moulds for the manufacture of local terra sigillata.[191]

The Romans used stibnite to decolourize glass, the production of which ended after they lost control of its Dacian mines.[192]

Religion

Inscriptions and sculpture in Dacia reveal a wide variety in matters of religion. Deities of the official state religion of Rome appear alongside those originating in Greece, Asia Minor, and Western Europe;[193] of these, 43.5% have Latin names.[35] The major gods of the Roman pantheon are all represented in Dacia:[193] Jupiter, Juno, Minerva, Venus, Apollo, Liber, Libera, and others.[194] The Roman god Silvanus was of unusual importance, second only to Jupiter.[195] He was frequently referred to in Dacia with the titles silvester and domesticus, which were also used in Pannonia.[196]

About 20% of Dacian inscriptions refer to Eastern cults such as that of Cybele and Attis, along with more than 274 dedications to Mithras, who was the most popular among soldiers.[197] The cult of the Thracian Rider was imported from Thrace and Moesia.[197] The Gallic horse goddess Epona is attested in Dacia, as are the Matronae.[197]

While the Dacians worshiped local divinities,[137] there is no evidence of any Dacian deity entering the Roman pantheon of gods,[137] and there is no evidence of any Dacian deity worshiped under a Roman name.[198] It is conjectured that the Dacians lacked an anthropomorphic conception of deity,[193] and that the Thraco-Dacian religion and their art was characterized by aniconism.[199] Dacian citadels dated to the reigns of Burebista and Decebalus have yielded no statues in their sanctuaries.[193] With the destruction of the main Dacian sacred site during Trajan's wars of conquest, no other site took its place. However, there were other cult sites of local spiritual significance, such as Germisara, which continued to be used during the Roman period, although religious practices at these sites were somewhat altered by Romanization, including the application of Roman names to the local spirits.[137]

Highly Romanized urban centres brought with them Roman funerary practices, which differed significantly from those pre-dating the Roman conquest.[200] Archaeological excavations have uncovered funerary art principally attached to the urban centres. Such excavations have shown that stelae were the favoured style of funerary memorial. However, other more sophisticated memorials have also been uncovered, including aediculae, tumuli, and mausoleums. The majority were highly decorated, with sculptured lions, medallions, and columns adorning the structures.[201]

This appears to be an urban feature only – the minority of cemeteries excavated in rural areas display burial sites that have been identified as Dacian, and some have been conjectured to be attached to villa settlements, such as Deva, Sălașu de Sus, and Cincis.[200]

Traditional Dacian funerary rites survived the Roman period and continued into the post-Roman era,[36] during which time the first evidence of Christianity begins to appear.[193]

Last decades of Dacia Traiana (235–271/275)

The 230s marked the end of the final peaceful period experienced in Roman Dacia.[202] The discovery of a large stockpile of Roman coins (around 8,000) at Romula, issued during the reigns of Commodus and Elagabalus, who was killed in 222 AD, has been taken as evidence that the province was experiencing problems before the mid-3rd century.[203] Traditionally, the accession of Maximinus Thrax (235–238) marks the start of a 50-year period of disorder in the Roman Empire, during which the militarization of the government inaugurated by Septimius Severus continued apace and the debasement of the currency brought the empire to bankruptcy.[204] As the 3rd century progressed, it saw the continued migration of the Goths, whose movements had already been a cause of the Marcomannic Wars,[205] and whose travels south towards the Danubian frontier continued to put pressure on the tribes who were already occupying this territory.[206] Between 236 and 238, Maximinus Thrax campaigned in Dacia against the Carpi,[207] only to rush back to Italy to deal with a civil war.[208] While Gordian III eventually emerged as Roman Emperor, the confusion in the heart of the empire allowed the Goths, in alliance with the Carpi, to take Histria in 238[209] before sacking the economically important commercial centres along the Danube Delta.[210]

Unable to deal militarily with this incursion, the empire was forced to buy peace in Moesia, paying an annual tribute to the Goths; this infuriated the Carpi who also demanded a payment subsidy.[209] Emperor Philip the Arab (244–249) ceased payment in 245[211] and the Carpi invaded Dacia the following year, attacking the town of Romula in the process.[203] The Carpi probably burned the castra of Răcari between 243 and 247.[104] Evidence suggests the defensive line of the Limes Transalutanus was probably abandoned during Philip the Arab's reign, as a result of the incursion of the Carpi into Dacia.[104] Ongoing raids forced the emperor to leave Rome and take charge of the situation.[212] The mother of the future emperor Galerius fled Dacia Malvensis at around this time before settling in Moesia Inferior.[213]

But the other Maximian (Galerius), chosen by Diocletian for his son-in-law, was worse, not only than those two princes whom our own times have experienced, but worse than all the bad princes of former days. In this wild beast there dwelt a native barbarity and a savageness foreign to Roman blood; and no wonder, for his mother was born beyond the Danube, and it was an inroad of the Carpi that obliged her to cross over and take refuge in New Dacia.

— Lactantius: Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died – Chapter IX[214]

At the end of 247 the Carpi were decisively beaten in open battle and sued for peace;[215] Philip the Arab took the title of Carpicus Maximus.[216] Regardless of these victories, Dacian towns began to take defensive measures. In Sucidava, the townspeople hurriedly erected a trapezoidal stone wall and defensive ditch, most likely the result of a raid by the barbarian tribes around 246 or 247. In 248 Romula enhanced the wall surrounding the settlement, again most likely as an additional defensive barrier against the Carpi.[203] An epigraph uncovered in Apulum salutes the emperor Decius (reigned 249–251) as restitutor Daciarum, the "restorer of Dacia".[217] On 1 July 251, Decius and his army were killed by the Goths during their defeat in the Battle of Abrittus (modern Razgard, Bulgaria).[218] Firmly entrenched in the territories along the lower Danube and the Black Sea's western shore, their presence affected both the non-Romanized Dacians (who fell into the Goth's sphere of influence)[219] and Imperial Dacia, as the client system that surrounded the province and supported its existence began to break apart.[220]

Decius appeared in the world, an accursed wild beast, to afflict the Church, – and who but a bad man would persecute religion? It seems as if he had been raised to sovereign eminence, at once to rage against God, and at once to fall; for, having undertaken an expedition against the Carpi, who had then possessed themselves of Dacia and Moesia, he was suddenly surrounded by the barbarians, and slain, together with great part of his army; nor could he be honored with the rites of sepulture, but, stripped and naked, he lay to be devoured by wild beasts and birds, – a fit end for the enemy of God.

— Lactantius: Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died – Chapter IV[221]

Continuing pressures during the reign of the emperor Gallienus (253–268) and the fracturing of the western half of the empire between himself and Postumus in Gaul after 260 meant that Gallienus' attention was principally focused on the Danubian frontier.[222] Repeated victories over the Carpi and associated Dacian tribes enabled him to claim the title Dacicus Maximus.[223] However, literary sources from antiquity (Eutropius,[224][225] Aurelius Victor,[226] and Festus[23]) write that Dacia was lost under his reign.[227] He transferred from Dacia to Pannonia a large percentage of the cohorts from the fifth Macedonica and thirteenth Gemina legions.[206] The latest coins at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Porolissum bear his effigy,[228] and the raising of inscribed monuments in the province virtually ceased in 260,[229] the year that marked the temporary breakup of the empire.[230]

Even the territories across the Danube, which Trajan had secured, were lost.

Coins were minted during the restoration of the empire (c. 270) under Aurelian which bear the inscription "DACIA FELIX" ("Fertile/Happy Dacia").[232] The pressing need to deal with the Palmyrene Empire meant Aurelian needed to settle the situation along the Danube frontier.[233] Reluctantly, and possibly only as a temporary measure, he decided to abandon the province.[233] The traditional date for Dacia's official abandonment is 271;[234] another view is that Aurelian evacuated his troops and civilian administration during 272–273,[235] possibly as late as 275.[236]

The province of Dacia, which Trajan had formed beyond the Danube, he gave up, despairing, after all Illyricum and Moesia had been depopulated, of being able to retain it. The Roman citizens, removed from the town and lands of Dacia, he settled in the interior of Moesia, calling that Dacia which now divides the two Moesiae, and which is on the right hand of the Danube as it runs to the sea, whereas Dacia was previously on the left.

The end result was that Aurelian established a new province of Dacia[235] called Dacia Aureliana with its capital at Serdica, previously belonging to Lower Moesia.[237][238] A portion of the Romanized population settled in the new province south of the Danube.[239] The provinces of Dacia Ripensis and Dacia Mediterranea would then be created out of the northern and southern parts of this province as it was re-organized over the following decades.[240]

After the Roman withdrawal

Consolidation of the frontier

The emperor Galerius once declared a complaint which the Romans were aware of: the Danube was the most challenging of all the empire's frontiers.[241] Aside from its enormous length, great portions of it did not suit the style of fighting which the Roman legions preferred.[242] To protect the provinces south of the Danube, the Romans retained a few military forts on the northern bank of the Danube long after the withdrawal from Dacia Traiana.[120] Aurelian kept a foothold at Drobeta, while a vexillation of the Thirteenth Legion (Legio XIII Gemina) was posted in Desa until at least 305 AD.[120] Coins bearing the image of emperor Gratian (reign 375–383 AD) have been uncovered at Dierna, possibly indicating that the town continued to function after the Roman withdrawal.[243]

In the years immediately after the withdrawal, Roman towns survived, albeit on a reduced level.[244] The previous tribes which had settled north of the Danube, such as the Sarmatians, Bastarnae, Carpi, and Quadi were increasingly pressured by the arrival of the Vandals in the north, while the Gepids and the Goths pressured them from the east and the northeast.[242] This forced the older tribes to push into Roman territory, weakening the empire's already stretched defences further. To gain entry into the empire, the tribes alternated between beseeching the Roman authorities to allow them in, and intimidating them with the threat of invasion if their requests were denied.[242] Ultimately, the Bastarnae were permitted to settle in Thrace, while the Carpi which survived were permitted to settle in the new province of Pannonia Valeria west of their homeland.[241] However, the Carpi were neither destroyed by other barbarian tribes, nor fully integrated into the Roman Empire. Those who survived on the borders of the empire were apparently called Carpodacae ("Carps from Dacia").[245]

By 291 AD, the Goths had recovered from their defeat at the hands of Aurelian, and began to move into what had been Roman Dacia.[246] When the ancestors of the Tervingi migrated into north-eastern Dacia, they were opposed by the Carpi and the non-Romanized Dacians. Defeating these tribes, they came into conflict with the Romans, who still attempted to maintain control along the Danube. Some of the semi-Romanized population remained and managed to co-exist with the Goths.[151] By 295 AD, the Goths had managed to defeat the Carpi and establish themselves in Dacia, now called Gothia;[247] the Romans recognised the Tervingi as a foederatus.[248] They occupied what was the eastern portion of the old province and beyond, from Bessarabia on the Dniester in the east to Oltenia in the west.[249] Until the 320s, the Goths kept the terms of the treaty and proceeded to settle down in the former province of Dacia, and the Danube had a measure of peace for nearly a generation.[248]

Around 295 AD, the emperor Diocletian reorganized the defences along the Danube, and established fortified camps on the far side of the river, from Sirmium (modern Serbia) to Ratiaria (near modern Archar, Bulgaria) and Durostorum.[250] These camps were meant to provide protection of the principal crossing points across the river, to permit the movement of troops across the river, and to function as observation points and bases for waterborne patrols.[251]

Late Roman incursions

During the reign of Constantine I, the Tervingi took advantage of the civil war between him and Licinius to attack the empire in 323 AD from their settlements in Dacia.[252] They supported Licinius until his defeat in 324; he was fleeing to their lands in Dacia when he was apprehended.[252] As a result, Constantine focused on aggressively pre-empting any barbarian activity on the frontier north of the Danube.[253] By 328 AD, he had constructed at Sucidava a new bridge across the Danube,[254] and repaired the road from Sucidava to Romula.[255] He also erected a military fort at Daphne (modern Spanțov, Romania).[256]

In early 336, Constantine personally led his armies across the Danube and crushed the Gothic tribes which had settled there, in the process recreating a Roman province north of the Danube.[257] In honor of this achievement, the Senate granted him the title of Dacicus Maximus, and celebrated it along with the 30th anniversary of his accession as Roman Emperor in mid 336.[257] The granting of this title has been seen by scholars such as Timothy Barnes as implying some level of reconquest of Roman Dacia.[258] However, the bridge at Sucidava lasted less than 40 years, as the emperor Valens discovered when he attempted to use it to cross the Danube during his campaign against the Goths in 367 AD.[254] Nevertheless, the castra at Sucidava remained in use until its destruction at the hands of Attila the Hun in 447 AD.[254]

Driven off their lands in what is now the region of Oltenia in southwestern Romania, the Tervingi moved towards Transylvania and came into conflict with the Sarmatians.[259] In 334, the Sarmatians asked Constantine for military help, after which he allowed the majority of them to settle peacefully south of the Danube.[260] The Roman armies inflicted a crushing defeat on the Tervingi.[259] The Tervingi signed a treaty with the Romans, giving a measure of peace until 367.[261]

The last major Roman incursion into the former province of Dacia occurred in 367 AD, when the emperor Valens used a diplomatic incident to launch a major campaign against the Goths.[262] Hoping to regain the trans-Danubian beachhead which Constantine had successfully established at Sucidava,[263] Valens launched a raid into Gothic territory after crossing the Danube near Daphne around 30 May; they continued until September without any serious engagements.[264] He tried again in 368 AD, setting up his base camp at Carsium, but was hampered by a flood on the Danube.[265] He therefore spent his time rebuilding Roman forts along the Danube. In 369, Valens crossed the river into Gothia, and this time managed to engage the Tervingi, defeating them, and granting them peace on Roman terms.[266]

This was the final attempt by the Romans to maintain a presence in the former province. Soon after, the westward push by the Huns put increased pressure on the Tervingi, who were forced to abandon the old Dacian province and seek refuge within the Roman Empire.[267] Mismanagement of this request resulted in the death of Valens and the bulk of the eastern Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD.[268]

Although the region of Dacia to the north of the Danube was never re-conquered afterward, in the mid 6th century, the emperor Justinian built a large number of fortresses along the river to supplement border defenses, including the tower at Turnu Severin on the northern bank, and there were several Eastern Roman (early Byzantine) campaigns which occurred there in the last two decades of the 6th century and beginning of the 7th century, particularly under the emperor Maurice (reigned 582-602). The aim was to secure the Balkan provinces and Danubian frontier against continued incursions from Slavic and Avar raids, fortifying several settlements and fortresses along the river, but this also involved some victories over these enemies deeper into their lands to the north, including Pannonia as well.[269][270] However, despite these successes in re-establishing the frontier, in 602 a mutiny within the exhausted Byzantine army stationed north of the river in what was once Dacia (with the expectation that they would continue to stay and campaign there over the winter, despite pay cuts) caused the emperor to be overthrown by one of his generals, Phocas, culminating in the eventual collapse of Roman control of the Balkans over the coming decades as attention had to be turned east to Persian[271] and later Arab threats.

Controversy over the fate of the Daco-Romans

Based on the written accounts of ancient authors such as Eutropius, it had been assumed by some Enlightenment historians such as Edward Gibbon that the population of Dacia Traiana was moved south when Aurelian abandoned the province.[272][273] However, the fate of the Romanized Dacians, and the subsequent origin of the Romanians, became mired in controversy, stemming from political considerations originating during the 18th and 19th centuries between Romanian nationalists and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[274][36]

One theory states that the process which formed the Romanian people began with the Romanization of Dacia and the existence of a Daco-Roman populace which did not completely abandon the province after the Roman withdrawal in 275 AD.[275] Archaeological evidence obtained from burial sites and settlements supports the contention that a portion of the native population continued to inhabit what was Roman Dacia.[276] Pottery remains dated to the years after 271 AD in Potaissa,[158] and Roman coinage of Marcus Claudius Tacitus and Crispus (son of Constantine I) uncovered in Napoca demonstrate the continued survival of these towns.[277] In Porolissum, Roman coinage began to circulate again under Valentinian I (364–375); meanwhile, local Daco-Romans continued to inhabit Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, fortifying the amphitheatre against barbarian raids.[228] According to this theory, the Romanian people continued to develop under the influence of the Roman Empire until the beginning of the 6th century, and as long as the empire held territory on the southern bank of the Danube and in Dobruja, it influenced the region to the river's north.[275] This process was facilitated by the trading of goods and the movement of peoples across the river.[275] Roman towns endured in Dacia's middle and southern regions, albeit reduced in size and wealth.[244]

The competing theory states that the transfer of Dacia's diminished population overlapped with the requirement to repopulate the depleted Balkans.[278] Although it is possible that some Daco-Romans remained behind, these were few in number.[279] Toponymic changes tend to support a complete withdrawal from Roman Dacia, as the names for Roman towns, forts, and settlements fell completely out of use.[280] Repeated archaeological investigations from the 19th century onwards have failed to uncover definitive proof that a large proportion of the Daco-Romans remained in Dacia after the evacuation;[281] for example, traffic in Roman coins in the former province after 271 show similarities to modern Slovakia and the steppe in what is today Ukraine.[282] On the other hand, linguistic data and place names[283] attest to the beginnings of the Romanian language in Lower Moesia, or other provinces south of the Danube of the Roman Empire.[284] Toponymic analysis of place names in the former Roman Dacia north of the Danube suggests that, on top of names which have a Thracian, Scytho-Iranian, Celtic, Roman and Slavonic origin, there are some un-Romanized Dacian place names which were adopted by the Slavs (possibly via the Hungarians) and transmitted to the Romanians, in the same way that some Latin place names were transmitted to the Romanians via the Slavs (such as "Olt").[285]

According to those who posit the continued existence of a Romanized Dacian population after the Roman withdrawal, Aurelian's decision to abandon the province was solely a military decision with respect to moving the legions and auxiliary units to protect the Danubian frontier.[286] The civilian population of Roman Dacia did not treat this as a prelude to a coming disaster; there was no mass emigration from the province, no evidence of a sudden withdrawal of the civilian population, and no widespread damage to property in the aftermath of the military withdrawal.[286]

Linguistic analysis shows that at least a couple of places that retained their Latin name until the arrival of Slavic speaking communities were from an emerging Romance language different to Romanian. These toponyms, Cluj and Bigla, retained the clusters -cl- and -gl-, which in Romanian became ch and gh respectively.[287] However, this phonetic evolution may have occurred later in the Romanian language than the 5th-6th centuries when the Slavs arrived, as evidenced by the partial survival of these consonant clusters in the closely related Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian, as well as in languages that borrowed from Romanian. However, of note there was also a Pannonian Latin variety that existed in the nearby province of Pannonia, which subsequently died out in Late Antiquity.

See also

- Dacia Mediterranea

- Dacia Ripensis

- History of Romania

- List of ancient cities in Thrace and Dacia

- List of Roman governors of Dacia Traiana

- Roman provinces

Notes

- ^ Caracalla's activities in Dacia need to be placed within the verified dates in his progress to the east. On 11 August 213, Caracalla crossed the frontier at Raetia into Barbaricum, while in 8 October 213, his victories over the Germanic tribes were announced at Rome, and sometime between 17 December 213 and 17 January 214, he was at Nicomedia – see Opreanu 2015, pp. 18–19

References

- ^ a b c d e f Oltean 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Pop 1999, p. 14.

- ^ a b Georgescu 1991, p. 4.

- ^ Mócsy 1974, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Burns 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Schmitz 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Bunson 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Pârvan 1928, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b c Oltean 2007, p. 52.

- ^ a b Burns 2003, p. 183.

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 138.

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 192.

- ^ Marko Popović (2011). Dragan Stanić (ed.). Српска енциклопедија, том 1, књига 2, Београд-Буштрање [Serbian Encyclopedia, Vol. I, Book 2, Beograd-Buštranje]. Matica Srpska, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zavod za udžbenike, Novi Sad-Belgrade. p. 37. ISBN 978-86-7946-097-4.

- ^ a b c Oltean 2007, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Pop 1999, p. 16.

- ^ MacKendrick 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 102.

- ^ Pop 1999, p. 17.

- ^ a b Bennett 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Pliny the Younger & 109 AD, Book VIII, Letter 4.

- ^ a b Festus & 379 AD, VIII.2.

- ^ Gibbon 1816, p. 6.

- ^ a b Bennett 1997, p. 104.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 98.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 105.

- ^ Alexander M. Gillespie (2011). A History of the Laws of War: Volume 2, The Customs and Laws of War with Regards to Civilians in Times of Conflict. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-84731-862-6.

- ^ Flavius Eutropius (2019). Delphi Complete Works of Eutropius (Illustrated). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-78877-961-6.

- ^ Ian Haynes; W.S. Hanson (204). "Roman Dacia - The Making of a Provincial Society". Journal of Roman Archaeology: 77. ISBN 978-1-887829-56-4.

- ^ Georgescu 1991, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Oltean 2007, p. 57.

- ^ a b Burns 2003, p. 103.

- ^ a b Köpeczi 1994, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Georgescu 1991, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ellis 1998, pp. 220–237.

- ^ Parker 2010, p. 266.

- ^ Wilkes 2000, p. 591.

- ^ Köpeczi 1994, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Bennett 1997, p. 169.

- ^ Köpeczi 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Petolescu 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Bury 1893, p. 490.

- ^ Opper 2008, pp. 55, 67.

- ^ Webster 1998, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Opper 2008, p. 67.

- ^ a b Bury 1893, p. 499.

- ^ Bury 1893, p. 493.

- ^ a b c MacKendrick 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Mócsy 1974b, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e Oltean 2007, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Oltean 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Köpeczi 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Bury 1893, p. 500.

- ^ a b c d MacKendrick 2000, p. 206.

- ^ MacKendrick 2000, p. 127.

- ^ Bunson 2002, p. 24.

- ^ MacKendrick 2000, p. 152.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 2000, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Grant 1996, p. 20.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Birley 2000, p. 132.

- ^ Bury 1893, pp. 542–543.

- ^ a b Birley 2000, p. 145.

- ^ McLynn 2011, p. 324.

- ^ Potter 1998, p. 274.

- ^ Chapot 1997, p. 275.

- ^ Köpeczi 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Grant 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Bury 1893, p. 543.

- ^ a b Köpeczi 1994, p. 86.

- ^ Oliva 1962, p. 275.

- ^ Bury 1893, p. 544.

- ^ Nemeth 2005, pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b c d Birley 2000, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Birley 2000, p. 164.