DPLL algorithm

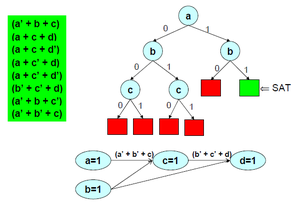

After 5 fruitless attempts (red), choosing the variable assignment a=1, b=1 leads, after unit propagation (bottom), to success (green): the top left CNF formula is satisfiable. | |

| Class | Boolean satisfiability problem |

|---|---|

| Data structure | Binary tree |

| Worst-case performance | |

| Best-case performance | (constant) |

| Worst-case space complexity | (basic algorithm) |

In logic and computer science, the Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland (DPLL) algorithm is a complete, backtracking-based search algorithm for deciding the satisfiability of propositional logic formulae in conjunctive normal form, i.e. for solving the CNF-SAT problem.

It was introduced in 1961 by Martin Davis, George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland and is a refinement of the earlier Davis–Putnam algorithm, which is a resolution-based procedure developed by Davis and Hilary Putnam in 1960. Especially in older publications, the Davis–Logemann–Loveland algorithm is often referred to as the "Davis–Putnam method" or the "DP algorithm". Other common names that maintain the distinction are DLL and DPLL.

Implementations and applications

The SAT problem is important both from theoretical and practical points of view. In complexity theory it was the first problem proved to be NP-complete, and can appear in a broad variety of applications such as model checking, automated planning and scheduling, and diagnosis in artificial intelligence.

As such, writing efficient SAT solvers has been a research topic for many years. GRASP (1996-1999) was an early implementation using DPLL.[1] In the international SAT competitions, implementations based around DPLL such as zChaff[2] and MiniSat[3] were in the first places of the competitions in 2004 and 2005.[4]

Another application that often involves DPLL is automated theorem proving or satisfiability modulo theories (SMT), which is a SAT problem in which propositional variables are replaced with formulas of another mathematical theory.

The algorithm

The basic backtracking algorithm runs by choosing a literal, assigning a truth value to it, simplifying the formula and then recursively checking if the simplified formula is satisfiable; if this is the case, the original formula is satisfiable; otherwise, the same recursive check is done assuming the opposite truth value. This is known as the splitting rule, as it splits the problem into two simpler sub-problems. The simplification step essentially removes all clauses that become true under the assignment from the formula, and all literals that become false from the remaining clauses.

The DPLL algorithm enhances over the backtracking algorithm by the eager use of the following rules at each step:

- Unit propagation

- If a clause is a unit clause, i.e. it contains only a single unassigned literal, this clause can only be satisfied by assigning the necessary value to make this literal true. Thus, no choice is necessary. Unit propagation consists in removing every clause containing a unit clause's literal and in discarding the complement of a unit clause's literal from every clause containing that complement. In practice, this often leads to deterministic cascades of units, thus avoiding a large part of the naive search space.

- Pure literal elimination

- If a propositional variable occurs with only one polarity in the formula, it is called pure. A pure literal can always be assigned in a way that makes all clauses containing it true. Thus, when it is assigned in such a way, these clauses do not constrain the search anymore, and can be deleted.

Unsatisfiability of a given partial assignment is detected if one clause becomes empty, i.e. if all its variables have been assigned in a way that makes the corresponding literals false. Satisfiability of the formula is detected either when all variables are assigned without generating the empty clause, or, in modern implementations, if all clauses are satisfied. Unsatisfiability of the complete formula can only be detected after exhaustive search.

The DPLL algorithm can be summarized in the following pseudocode, where Φ is the CNF formula:

Algorithm DPLL

Input: A set of clauses Φ.

Output: A truth value indicating whether Φ is satisfiable.

function DPLL(Φ)

// unit propagation:

while there is a unit clause {l} in Φ do

Φ ← unit-propagate(l, Φ);

// pure literal elimination:

while there is a literal l that occurs pure in Φ do

Φ ← pure-literal-assign(l, Φ);

// stopping conditions:

if Φ is empty then

return true;

if Φ contains an empty clause then

return false;

// DPLL procedure:

l ← choose-literal(Φ);

return DPLL(Φ ∧ {l}) or DPLL(Φ ∧ {¬l});

- "←" denotes assignment. For instance, "largest ← item" means that the value of largest changes to the value of item.

- "return" terminates the algorithm and outputs the following value.

In this pseudocode, unit-propagate(l, Φ) and pure-literal-assign(l, Φ) are functions that return the result of applying unit propagation and the pure literal rule, respectively, to the literal l and the formula Φ. In other words, they replace every occurrence of l with "true" and every occurrence of not l with "false" in the formula Φ, and simplify the resulting formula. The or in the return statement is a short-circuiting operator. Φ ∧ {l} denotes the simplified result of substituting "true" for l in Φ.

The algorithm terminates in one of two cases. Either the CNF formula Φ is empty, i.e., it contains no clause. Then it is satisfied by any assignment, as all its clauses are vacuously true. Otherwise, when the formula contains an empty clause, the clause is vacuously false because a disjunction requires at least one member that is true for the overall set to be true. In this case, the existence of such a clause implies that the formula (evaluated as a conjunction of all clauses) cannot evaluate to true and must be unsatisfiable.

The pseudocode DPLL function only returns whether the final assignment satisfies the formula or not. In a real implementation, the partial satisfying assignment typically is also returned on success; this can be derived by keeping track of branching literals and of the literal assignments made during unit propagation and pure literal elimination.

The Davis–Logemann–Loveland algorithm depends on the choice of branching literal, which is the literal considered in the backtracking step. As a result, this is not exactly an algorithm, but rather a family of algorithms, one for each possible way of choosing the branching literal. Efficiency is strongly affected by the choice of the branching literal: there exist instances for which the running time is constant or exponential depending on the choice of the branching literals. Such choice functions are also called heuristic functions or branching heuristics.[5]

Visualization

Davis, Logemann, Loveland (1961) had developed this algorithm. Some properties of this original algorithm are:

- It is based on search.

- It is the basis for almost all modern SAT solvers.

- It does not use learning or non-chronological backtracking (introduced in 1996).

An example with visualization of a DPLL algorithm having chronological backtracking:

- All clauses making a CNF formula

- Pick a variable

- Make a decision, variable a = False (0), thus green clauses becomes True

- After making several decisions, we find an implication graph that leads to a conflict.

- Now backtrack to immediate level and by force assign opposite value to that variable

- But a forced decision still leads to another conflict

- Backtrack to previous level and make a forced decision

- Make a new decision, but it leads to a conflict

- Make a forced decision, but again it leads to a conflict

- Backtrack to previous level

- Continue in this way and the final implication graph

Related algorithms

Since 1986, (Reduced ordered) binary decision diagrams have also been used for SAT solving.[citation needed]

In 1989-1990, Stålmarck's method for formula verification was presented and patented. It has found some use in industrial applications.[6]

DPLL has been extended for automated theorem proving for fragments of first-order logic by way of the DPLL(T) algorithm.[1]

In the 2010-2019 decade, work on improving the algorithm has found better policies for choosing the branching literals and new data structures to make the algorithm faster, especially the part on unit propagation. However, the main improvement has been a more powerful algorithm, Conflict-Driven Clause Learning (CDCL), which is similar to DPLL but after reaching a conflict "learns" the root causes (assignments to variables) of the conflict, and uses this information to perform non-chronological backtracking (aka backjumping) in order to avoid reaching the same conflict again. Most state-of-the-art SAT solvers are based on the CDCL framework as of 2019.[7]

Relation to other notions

Runs of DPLL-based algorithms on unsatisfiable instances correspond to tree resolution refutation proofs.[8]

See also

References

General

- Davis, Martin; Putnam, Hilary (1960). "A Computing Procedure for Quantification Theory". Journal of the ACM. 7 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1145/321033.321034. S2CID 31888376.

- Davis, Martin; Logemann, George; Loveland, Donald (1961). "A Machine Program for Theorem Proving". Communications of the ACM. 5 (7): 394–397. doi:10.1145/368273.368557. hdl:2027/mdp.39015095248095. S2CID 15866917.

- Ouyang, Ming (1998). "How Good Are Branching Rules in DPLL?". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 89 (1–3): 281–286. doi:10.1016/S0166-218X(98)00045-6.

- John Harrison (2009). Handbook of practical logic and automated reasoning. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–90. ISBN 978-0-521-89957-4.

Specific

- ^ a b Nieuwenhuis, Robert; Oliveras, Albert; Tinelli, Cesar (2004), "Abstract DPLL and Abstract DPLL Modulo Theories" (PDF), Proceedings Int. Conf. on Logic for Programming, Artificial Intelligence, and Reasoning, LPAR 2004, pp. 36–50

- ^ zChaff website

- ^ "Minisat website".

- ^ The international SAT Competitions web page, sat! live

- ^ Marques-Silva, João P. (1999). "The Impact of Branching Heuristics in Propositional Satisfiability Algorithms". In Barahona, Pedro; Alferes, José J. (eds.). Progress in Artificial Intelligence: 9th Portuguese Conference on Artificial Intelligence, EPIA '99 Évora, Portugal, September 21–24, 1999 Proceedings. LNCS. Vol. 1695. pp. 62–63. doi:10.1007/3-540-48159-1_5. ISBN 978-3-540-66548-9.

- ^ Stålmarck, G.; Säflund, M. (October 1990). "Modeling and Verifying Systems and Software in Propositional Logic". IFAC Proceedings Volumes. 23 (6): 31–36. doi:10.1016/S1474-6670(17)52173-4.

- ^ Möhle, Sibylle; Biere, Armin (2019). "Backing Backtracking". Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing – SAT 2019 (PDF). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11628. pp. 250–266. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-24258-9_18. ISBN 978-3-030-24257-2. S2CID 195755607.

- ^ Van Beek, Peter (2006). "Backtracking search algorithms". In Rossi, Francesca; Van Beek, Peter; Walsh, Toby (eds.). Handbook of constraint programming. Elsevier. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-444-52726-4.

Further reading

- Malay Ganai; Aarti Gupta; Dr. Aarti Gupta (2007). SAT-based scalable formal verification solutions. Springer. pp. 23–32. ISBN 978-0-387-69166-4.

- Gomes, Carla P.; Kautz, Henry; Sabharwal, Ashish; Selman, Bart (2008). "Satisfiability Solvers". In Van Harmelen, Frank; Lifschitz, Vladimir; Porter, Bruce (eds.). Handbook of knowledge representation. Foundations of Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 3. Elsevier. pp. 89–134. doi:10.1016/S1574-6526(07)03002-7. ISBN 978-0-444-52211-5.