Cross-bedding

In geology, cross-bedding, also known as cross-stratification, is layering within a stratum and at an angle to the main bedding plane. The sedimentary structures which result are roughly horizontal units composed of inclined layers. The original depositional layering is tilted, such tilting not being the result of post-depositional deformation. Cross-beds or "sets" are the groups of inclined layers, which are known as cross-strata.

Cross-bedding forms during deposition on the inclined surfaces of bedforms such as ripples and dunes; it indicates that the depositional environment contained a flowing medium (typically water or wind). Examples of these bedforms are ripples, dunes, anti-dunes, sand waves, hummocks, bars, and delta slopes.[1] Environments in which water movement is fast enough and deep enough to develop large-scale bed forms fall into three natural groupings: rivers, tide-dominated coastal and marine settings.[2]

Significance

Cross-beds can tell geologists much about what an area was like in ancient times. The direction the beds are dipping indicates paleocurrent, the rough direction of sediment transport. The type and condition of sediments can tell geologists the type of environment (rounding, sorting, composition...). Studying modern analogs allows geologists to draw conclusions about ancient environments. Paleocurrent can be determined by seeing a cross-section of a set of cross-beds. However, to get a true reading, the axis of the beds must be visible. It is also difficult to distinguish between the cross-beds of a dune and the cross-beds of an antidune. (Dunes dip downstream while antidunes dip upstream.)[1]

The direction of motion of the cross-beds can show ancient flow or wind directions (called paleocurrents). The foresets are deposited at the angle of repose (~34 degrees from the horizontal), so geologists are able to measure dip direction of the cross-bedded sediments and calculate the paleoflow direction. However, most cross-beds are not tabular, they are troughs[citation needed]. Since troughs can give a 180 degree variation of the dip of foresets, false paleocurrents can be taken by blindly measuring foresets. In this case, true paleocurrent direction is determined by the axis of the trough. Paleocurrent direction is important in reconstructing past climate and drainage patterns: sand dunes preserve the prevalent wind directions, and current ripples show the direction rivers were moving.

Formation

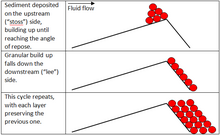

Cross-bedding is formed by the downstream migration of bedforms such as ripples or dunes[3] in a flowing fluid. The fluid flow causes sand grains to saltate up the stoss (upstream) side of the bedform and collect at the peak until the angle of repose is reached. At this point, the crest of granular material has grown too large and will be overcome by the force of the moving water, falling down the lee(downstream) side of the dune. Repeated avalanches will eventually form the sedimentary structure known as cross-bedding, with the structure dipping in the direction of the paleocurrent.

The sediment that goes on to form cross-stratification is generally sorted before and during deposition on the "lee" side of the dune, allowing cross-strata to be recognized in rocks and sediment deposits.[4]

The angle and direction of cross-beds are generally fairly consistent. Individual cross-beds can range in thickness from just a few tens of centimeters, up to hundreds of feet or more depending upon the depositional environment and the size of the bedform.[5] Cross-bedding can form in any environment in which a fluid flows over a bed with mobile material. It is most common in stream deposits (consisting of sand and gravel), tidal areas, and in aeolian dunes.

Internal sorting patterns

Cross-bedded sediments are recognized in the field by the many layers of "foresets", which are the series of layers that form on the downstream or lee side of the bedform (ripple or dune). These foresets are individually differentiable because of small-scale separation between layers of material of different sizes and densities.

Cross-bedding can also be recognized by truncations in sets of ripple foresets, where previously-existing stream deposits are eroded by a later flood, and new bedforms are deposited in the scoured area.

Geometries

Cross-bedding can be subdivided according to the geometry of the sets and cross-strata into subcategories. The most commonly described types are tabular cross-bedding and trough cross-bedding. Tabular cross-bedding, or planar bedding consists of cross-bedded units that are extensive horizontally relative to the set thickness and that have essentially planar bounding surfaces.[3] Trough cross-bedding, on the other hand, consists of cross-bedded units in which the bounding surfaces are curved, and hence limited in horizontal extent.[3]

Tabular (planar) cross-beds

Tabular (planar) cross-beds consist of cross-bedded units that are large in horizontal extent relative to set thickness and that have essentially planar bounding surfaces. The foreset laminae of tabular cross-beds are curved so as to become tangential to the basal surface.[3]

Tabular cross-bedding is formed mainly by migration of large-scale, straight-crested ripples and dunes. It forms during lower-flow regimes. Individual beds range in thickness from a few tens of centimeters to a meter or more, but bed thickness down to 10 centimeters has been observed.[6] Where the set height is less than 6 centimeters and the cross-stratification layers are only a few millimeters thick, the term cross-lamination is used, rather than cross-bedding. Cross-bed sets occur typically in granular sediments, especially sandstone, and indicate that sediments were deposited as ripples or dunes, which advanced due to a water or air current.[7]

Trough cross-beds

Cross-beds are layers of sediment that are inclined relative to the base and top of the bed they are associated with. Cross-beds can tell modern geologists many things about ancient environments such as- depositional environment, the direction of sediment transport (paleocurrent) and even environmental conditions at the time of deposition. Typically, units in the rock record are referred to as beds, while the constituent layers that make up the bed are referred to as laminae, when they are less than 1 cm thick and strata when they are greater than 1 cm in thickness.[1] Cross-beds are angled relative to either the base or the top of the surrounding beds. As opposed to angled beds, cross-beds are deposited at an angle rather than deposited horizontally and deformed later on.[8] Trough cross-beds have lower surfaces which are curved or scoop shaped and truncate the underlying beds. The foreset beds are also curved and merge tangentially with the lower surface. They are associated with sand dune migration.[9]

Sediment

The shape of the grains and the sorting and composition of sediment can provide additional information on the history of cross-beds. Roundness of the grains, limited variation in grain size, and high quartz contents are generally attributed to longer histories of weathering and sediment transport. For example: well-rounded, and well-sorted sand that is mostly composed of quartz grains is commonly found in beach environments, far from the source of the sediment. Poorly sorted and angular sediment that is composed of a diversity of minerals is more commonly found in rivers, near the source of the sediment.[8] However, older sedimentary deposits are frequently eroded and re-mobilized. Thus, a river may well erode an older formation of well-rounded, well-sorted beach sands of nearly pure quartz.

Environments

Rivers

Flows are characterized by climate (snows, rain, and ice melting) and gradient. Discharge variations measured on a variety of time scales can change water depth, and speed. Some rivers can be characterized by a predictable seasonably controlled hydrograph (reflecting snow melt or rainy season). Others are dominated by durational variations characteristic of alpine glaciers run-off or random storm events, which produce flashy discharge. Few rivers have a long term record of steady flow in the rock record.[2]

Bed forms are relatively dynamic sediment storage bodies with response times that are short relative to major changes in flow characteristics. Large scale bed forms are periodic and occur in the channel (scaled to depth). Their presence and morphologic variability have been related to flow strength expressed as mean velocity or shear stress.[2]

In a fluvial environment, the water in a stream loses energy and its ability transport sediment. The sediment "falls" out of the water and is deposited along a point bar. Over time the river may dry up or avulse and the point bar may be preserved as cross-bedding.

Tide-dominated

Tide dominated environments include:

- Coastal water bodies that are partially enclosed by topography, yet have a free connection to the sea.

- Coast lines that have a tidal range of greater than one meter.

- Areas in which the water run-off volume is low relative to the tidal volume or impact.

In general, the greater the tidal range the greater the maximum flow strength.[2] Cross-stratification in tidal-dominated areas can lead to the formation of Herringbone cross-stratification.

Although the flow direction reverses regularly, the flow patterns of flood on ebb currents commonly do not coincide. Consequently, the water and transport sediment may follow a roundabout route in and out of the estuary. This leads to spatially varied systems where some parts of the estuary are flood dominated and other parts are ebb dominated. The temporal and spatial variability of flow and sediment transport, coupled with regular fluctuating water levels creates a variety of bed form morphology.[2]

Shallow marine

Large scale bed forms occur on shallow, terrigenous or carbonate clastic continental shelves and epicontinental platforms which are affected by strong geostrophic currents, occasional storm surges and/or tide currents.[2]

Aeolian

In an aeolian environment, cross-beds often exhibit inverse grading due to their deposition by grain flows. Winds blow sediment along the ground until they start to accumulate. The side that the accumulation occurs on is called the windward side. As it continues to build, some sediment falls over the end. This side is called the leeward side. Grain flows occur when the windward side accumulates too much sediment, the angle of repose is reached and the sediment tumbles down. As more sediment piles on top the weight causes the underlying sediment to cement together and form cross-beds.[8]

References

- ^ a b c Collinson, J.D., Thompson, D.B., 1989, Sedimentary Structures (2nd ed): Academic Division of Unwin Hyman Ltd, Winchester, MA, XXX p.

- ^ a b c d e f Ashley, G. (1990) "Classification of Large-Scale Subaqueous Bedforms: A New Look At An Old Problem." Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. 60.1: 160-172. Print.

- ^ a b c d Boggs, S., 2006, Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy (4th ed): Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, XXX p.

- ^ Reesink, A.J.H. and Bridge, J.S., 2007 "Influence of superimposed bedforms and flow unsteadiness on formation of cross strata in dunes and unit bars." Sedimentary Geology, 202, 1-2, p. 281-296 doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2007.02.00508/2002.

- ^ Bourke, Lawrence, and McGarva, Roddy. "Go With The Flow: Part I Palaeotransport Analysis ." Task Geoscience. N.p., 08/2002. Web. 2 Nov 2010. <"Task Geoscience - the Borehole Image and Dipmeter Experts". Archived from the original on 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2010-12-02.>

- ^ Stow, A.V., 2009, Sedimentary rocks in the field. A color guide (3rd ed.) print.

- ^ Hurlbut, C. 1976. The Planet We Live On, An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Earth Sciences. NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Print.

- ^ a b c Middleton, G., 2003, Encyclopedia of Sedimentary Rocks : <MPG Books, Cornwall, GB, XXX p.

- ^ McLane, Michael, Sedimentology, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp 95-97 ISBN 0-19-507868-3

- Monroe, James S. and Wicander, Reed (1994) The Changing Earth: Exploring Geology and Evolution, 2nd ed., St. Paul, Minn. : West, ISBN 0-314-02833-1, pp. 113–114.

- Rubin, David M. and Carter, Carissa L. (2006) Bedforms and cross-bedding in animation, Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM), Atlas Series 2, DVD #56002, ISBN 1-56576-125-1

- Prothero, D. R. and Schwab, F., 1996, Sedimentary Geology, pg. 43-64, ISBN 0-7167-2726-9