Crocus

| Crocus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Crocus sativus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Iridaceae |

| Subfamily: | Crocoideae |

| Tribe: | Ixieae |

| Genus: | Crocus L. |

| Type species | |

| Crocus sativus | |

| Sections | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Crocus (/ˈkroʊkəs/; plural: crocuses or croci) is a genus of seasonal flowering plants in the family Iridaceae (iris family) comprising about 100 species of perennials growing from corms. They are low growing plants, whose flower stems remain underground, that bear relatively large white, yellow, orange or purple flowers and then become dormant after flowering. Many are cultivated for their flowers, appearing in autumn, winter, or spring. The flowers close at night and in overcast weather conditions. The crocus has been known throughout recorded history, mainly as the source of saffron. Saffron is obtained from the dried stigma of Crocus sativus, an autumn-blooming species. It is valued as a spice and dyestuff, and is one of the most expensive spices in the world. Iran is the center of saffron production. Crocuses are native to woodland, scrub, and meadows from sea level to alpine tundra from the Mediterranean, through North Africa, central and southern Europe, the islands of the Aegean, the Middle East and across Central Asia to Xinjiang in western China. Crocuses may be propagated from seed or from daughter cormels formed on the corm, that eventually produce mature plants. They arrived in Europe from Turkey in the 16th century and became valued as an ornamental flowering plant.

Description

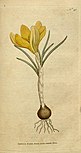

Atlas des plantes de France, 1891

General

Crocus display the general characteristics of family Iridaceae, which include basal cauline (arising from the aerial stem) leaves that sheath the stem base, hermaphrodite flowers that are relatively large and showy, the perianth petaloid with two whorls of three tepals each and septal nectaries. The flowers have three stamens and a gynoecium of three united carpels and an inferior ovary, three locules and axile placentation with fruit that is a loculicidal capsule.[2]

Crocus is an acaulescent (lacking a visible lower stem above ground) diminutive seasonal cormous (growing from corms) herbaceous perennial geophytic genus.[3] The corms are symmetrical and globose or oblate (round in shape with flatted tops and bottoms), and are covered with tunic leaves that are fibrous, membranous or coriaceous (leathery). The corms produce fibrous roots, and contractile roots which adjust the corms depth in the soil, which may be pulled as deep as 20 centimetres (8 in) into the soil.[4][5]The roots appear randomly from the lower part of the corm, but in a few species, from a basal ridge.[6]

Leaves

Plants produce several basal linear bifacial green leaves that arise from the corms. These are adaxially (upper surface facing axis) flat or channelled with pale median stripes, while the opposite (abaxial) surface is strongly keeled, with two grooves on either side. The leaves have a distinctive shape in cross-section, being boat-shaped with two lateral arms with margins recurved inwardly towards the central ridged keel, forming the sides of the "boat". The keel may be square or rectangular, but is lacking in C. carpetanus. The pale central stripe is caused by parenchymatous cells which lack chloroplasts and may contain air spaces.[7] The leaves are from 5 to 30 millimetres (3⁄16 to 1+3⁄16 in) wide and 10 to 118 centimetres (4 to 46 in) long. The leaf-like bracts are membranous, while the smaller bracteoles are either membranous or absent.[4][5] The leaf bases are surrounded by up to 5 membranous sheaths called cataphylls, a specialised leaf. The bases of the cataphylls form the corm tunic, and their number varies from 3 to 6, and enclose the true leaves (euphylls), bracts, bracteoles and flowering stalk.[8][9]

Flowers

The number of peduncles (flower stems) vary from one to several and remain underground, emerging only at the fruiting stage, bearing flowers that are solitary or several, so that a true scape is absent. The flowers are pedicellate (attached to the peduncle by a short subterranean pedicel stalk). The pedicel is sometimes subtended (below pedicel) by a membranous, sheathing prophyll (leaf-like structure).[4][5]

The showy, salver to cup-shaped, single or clustered actinomorphic flowers taper off into a narrow tube; the flowers emerge from the ground, and can be white, yellow, lilac to dark purple, or variegated in cultivars. The flower tube is long, cylindrical and slender, expanding apically. The floral tube is long and narrow with 6 lobes in 2 whorls. The perianth is 3+3 (3 sepals+3petals) and gamophyllous (with fused segments). The tepal whorls are similar, equal or subequal with a smaller inner whorl, and cupped to outspread. The bracts are membranous, but the inner ones are sometimes lacking.[4][5][10]

The 3 stamens are erect and linear and inserted in the throat of the perianth tube, with anthers shorter than the filaments. Pollen grains are inaperturate (apertures absent) but sometimes spiraperturate (spiral shaped).[11] Each flower has a single style which is exserted (projecting beyond the corolla tube) and slender distally with three to many branches. The branches are highly variable, being short or long, and simple, bifurcate (dividing in two) or multifid and sometimes distally flattened. The inferior ovary has 3 carpels with axile placentation. It remains underground, and as the seeds ripen, the pedicel (stem of the flower) grows longer - so the fruit is above the soil surface.[4][5][12]

Fruit and seed

The fruit is a small membranous capsule, ellipsoid or oblong-ellipsoid in shape and the many seeds are globose to ellipsoid. The seed surface is highly variable, including papillate (covered in small protuberances), digitiform (finger-like) and other epidermal cell types. In some species the seeds are arillate, with fleshy appendages. Crocus seeds have both inner and outer integuments and in some species the outer epidermis may display long papillae. Embryo-sac development is Polygonum type. Dehiscence (splitting of the capsule to release the seed) is of the loculicidal type in which it splits through the wall of the locules leaving the septa that separate them intact.[13][10][14]

Karyology

Crocus has extensive aneuploidy (abnormal number of chromosomes), with some uncertainty as to the base number of chromosomes. The chromosome numbers shows extreme variability, ranging from 2n=6 to 2n=70 even within a single species.[15][11]

Phytochemistry

The Iridaceae contain a wide range of phenolic compounds. However, 6-Hydroxyflavones are found only in Crocus, which is also characterised by the presence of crocins, water-soluble yellow carotenoids, in the floral tissues. Crocin is a diester of crocetin, responsible for the colour of the styles and stigma of C. sativus, and hence saffron.[16][17] A few species contain mangiferin, a glucosylxanthone.[18][19]

While the flowers may vary dramatically between species, there is little variation in the leaves,[20] but sufficient variability in corm tunics that they may be used as an aid in differentiating taxa.[21]

- Crocus structuresCorms with net-like papery tunicClosed flower with leavesFlower with 3 stamens surrounding central style and stigma3 stamens and styleCentral stigma in opening flowerExserted style & trifid stigma projecting above corollaLateral viewCapsules (seedpods) with seeds

Taxonomy

History

Tractatus de Herbis ca. 1300–1330

John Gerard 1597

Hortus Eystettensis 1613

The crocus was well known to the ancients,[22] being described at least as early as Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BC),[a][24] and was introduced into Britain by the Romans, where the saffron crocus was used as a dyestuff. It was reintroduced into Western Europe by the Crusaders. The crocus is mentioned in mediaeval and later herbals, one of the earliest being the 14th century Tractatus de Herbis.[25][26] William Turner (1548) states that the crocus is referred to as saffron in English, implying that only C. sativus was known at that time.[27] However, by 1597 John Gerard writes of "sundry sorts" and uses the term saffron and crocus as interchangeable. He included both spring and autumn flowering crocus, but distinguished Wild Saffron (Crocus) from Meadow Saffron (Colchicum). He described eleven forms. Some of his specimens were obtained from Clusius.[28][29] In the following century, John Parkinson in a more detailed account was more careful to include separate chapters for Colchicum, with the common name of meadow saffron, from Crocus or saffron. Parkinson (1656) states that there are "divers sorts of saffrons" describing 27 spring flowering plants and 4 autumn flowering ones, pointing out that only one of those was the true saffron crocus, which he called Crocus verus sativus autumnalis.[30] Similar accounts are found in continental European herbals, including those of l'Obel in Flanders (1576)[31] and Besler's Hortus Eystettensis in Bavaria (1613).[32]

The genus Crocus was first formally described by Linnaeus in 1753, with three taxa, and two species, C. sativus (type species), var. officinalis (now treated as a synonym of C. sativus) and var. vernus (now C. vernus) and C. bulbocodium (now Romulea bulbocodium). Thus Linnaeus recognised two taxa that are accepted as separate species in modern classifications, one vernal and one autumnal crocus, but incorrectly assumed they were only varieties of a single species, while his second species was actually from a closely related genus that was only recognised later (1772).[33] However, a subsequent re-examination of Linnaeus's specimens suggested the presence of several different species that he did not recognise as being separate.[34] Linnaeus' system, based on sexual characteristics, Crocus was classified as Triandra Monogynia (Three stamens, Single pistil).[35] Linnaeus's system was supplanted by the "natural" system which used a hierarchy of taxonomic ranks based on weighting of the importance of structural characteristics of the plant. Jussieu (1789) placed the genus Crocus in his Ordo (family) Irides or Les iris, as a member of the class Stamina epigyna (stamens inserted above the ovary) as part of the monocotyledons, the first level of the division of the flowering plants.[36]

One of the first monographs of the genus appeared in 1809, by Haworth,[37] followed in 1829 by that of Sabine,[38][29] and Herbert in 1847.[39] In 1853, Lindley continued the placement of Crocus as one of 53 genera in Iridaceae, which he included in a higher order of monocotyledons, the Narcissales.[40] Baker published a monograph on the genus in 1874, adopting a very different schema to that of Herbert.[41] In 1883, Bentham and Hooker described the Irideae (Iridaceae) as having more than 700 species, and divided it into 3 tribes and further into subtribes. Tribe Sysyrinchieae as having 2 subtribes, including Ixieae. The latter was circumscribed with four genera, Crocus, Syringodea, Galaxia (Moraea) and Romulea.[42] This circumscription has remained stable since, with the exception of Moraea which properly belongs in a separate tribe. The most influential monograph of the nineteenth century was that of Maw (1886), which forms the basis of modern understanding of the genus. Maw built on the work of Herbert, rejecting Baker's classification.[43] The availability of molecular phylogenetic methods in the late twentieth century has shown that the Iridaceae properly belong within the order Asparagales.[44]

Botanical illustration

The scientific study of the genus in the late eighteenth century was accompanied by detailed descriptions with Botanical illustrations, such as those of William Curtis (1787) and Sims (1803),[45] that appeared in Curtis' Botanical Magazine, with illustrations by Sydenham Edwards.[46] Other illustrations are found in monographs such as those of Haworth (1809)[37] and Sabine (1830), illustrated by Charles John Robertson.[38] The largest collection is found in the most comprehensive monograph, that of Maw (1886).[47] Other sources include the portfolios of plates, such as the survey of the plants of France by Masclef (1891). At that time only C. sativus and C. vernus were included in the Flora of France.[48]

Curtis's Botanical Magazine 1787

A Haworth 1809

Sabine 1830

Maw 1886

Phylogeny

The genus Crocus belongs to the monocot family Iridaceae (iris family), specifically the large subfamily Crocoideae. Within that subfamily, crocus is placed on the tribe, Ixieae (synonym Croceae),[b] one of five. The Ixieae are then subdivided into subtribes, with the genera Crocus, Romulea and Syringodea forming subtribe Romuleinae. The Romuleinae have been characterised within the Ixieae by progressively reduced aerial stems.[51] solitary flowers on the stem branches and woody tunics on the corms. They also often have divided style branches. However, Crocus corm tunics are fibrous and membranous rather than woody as in Syringodea. Also, Crocus has a ridged and often keeled abaxial leaf surface, while that of Syringodea is rounded, and the midline adaxial translucency of Crocus is lacking in Syringodea. Romulea is principally distinguished from the other two genera by generally having aerial stems or at least an ovary at ground level, compared with the other acaulescent genera, other differences include unifacial rather than bifacial leaves and the pollen structure.[52][51]

Within the Romuleinae, Crocus is a sister group to Syringodea, the two genera forming a sister group to Romulea.[49][53][15]

Subdivision

The genus Crocus consists of about 200 accepted species, which continue to increase, and has undergone a large number of taxonomic classifications.[29] The genus has often been divided into sections, beginning with that of Haworth (1809)[37] who described two sections based on the presence or absence of hairs in the throat of the flower, while Sabine was the first to realise the importance of the presence or absence of a basal spathe (prophyll) in dividing the genus into two sections,[38] a practice followed by Herbert.[39] However, Sabine's practice of using trinomials for varieties such as C. sulphureus concolor is no longer accepted, although Herbert somewhat similarly used varieties and subvarieties, e.g. C. vernus var.1 Communis subvar. 1. Obovatus. Herbert also used geographical distribution as a basis of classification.[29] By the late 19th century Maw (1886),[47] following Herbert, subdivided the genus into two divisions, the Involucrati and the Nudiflori, and then further divided it into six sections and lastly by flowering times (spring or autumn). Although rejecting the concept of subvarieties, he placed even more emphasis on geography.[54][15][55][29]

The most widely accepted system, that proposed by Brian Mathew in 1982[56] was based on Maw's system, but with less emphasis on flowering times. This mainly depended on three character states:

and included 81 species, however, one of these, Crocus medius was later recognized as a synonym of Crocus nudiflorus.[15][53]

The genus, as described by Mathew, consisted of two subgenera, Crocirus (monotypic for Crocus banaticus) and Crocus including the remainder of the species, based on whether the anthers were introrse or extrorse (dehiscence directed towards or away from centre of flower) respectively. Subgenus Crocus was then divided into two sections, Crocus and Nudiscapus, based on the presence or absence of the prophyll. Each section was then further divided into six series of Crocus and nine of Nudiscapus. These series were defined by the division of the style, the corm tunic, flowering time, leaf structure, presence of a bracteole and anther colour. Mathew also introduced the concept of subspecies, including 50 in all, by giving similar but different forms subspecies status if geographically separated, resulting in about 140 distinct taxa.[15] The seven species and ten subspecies discovered since then have been integrated into revisions of this classification, though new species continue to be described,[57][58][59][53] leading to estimates of at least 200 species.[60][29]

Speciation

Crocus populations have extremely high infra-specific variability with a very diverse spectrum of morphological and phenotypical varieties, while many individual specimens from different species may closely resemble each other. Based on such morphological differences between isolated populations many new species have been named, but without a definition of new species based on molecular and/or karyological information, species can not be confirmed, creating difficulties in determining speciation and hence the exact number of species.[61][62] The situation is even more complex once hybridisation (combination of taxa) and introgression (transfer of genetic material) are considered.[63][29]

Molecular phylogeny

The availability of molecular phylogeny methods revealed problems with the traditional systems based on morphology alone. The first analysis of the complete genus was carried out by Mathew and colleagues in 2008 using nucleotide sequences from plastid regions. In particular, the DNA data suggest there are no grounds for isolating C. banaticus in its own subgenus Crociris, though it is a unique species in the genus. Because it has a prophyll at the base of the pedicel, it therefore would fall within section Crocus, although its exact relationship to the rest of the subgenus remains unclear.[53]

Of the 15 series in the Mathew scheme, only seven were monophyletic, and in particular the largest series, Biflori and Reticulati, which include a third of all species, were non-monophyletic. Another anomalous species, C. baytopiorum, should now be placed in a series of its own, series Baytopi. C. gargaricus subsp. herbertii has been raised to species status, as C. herbertii. The autumn-flowering C. longiflorus, the type species of series Longiflori (long regarded by Mathew as "a disparate assemblage"), appeared to lie within series Verni. In addition, the position of C. malyi was currently unclear.[53]

DNA analysis and morphological studies suggest further that series Reticulati, Biflori and Speciosi are "probably inseparable", C. adanensis and C. caspius should probably be removed from Biflori, C. adanensis falls in a clade with C. paschei as a sister group to the species of series Flavi and C. caspius appears to be sister to the species of series Orientales.[53][15]

The study showed "no support for a system of sections as currently defined", although, despite the many inconsistencies between Mathew's 1982 classification and the current hypothesis, "the main assignment of species to the sections and series of that system is actually supported". The authors state, "further studies are required before any firm decisions about a hierarchical system of classification can be considered" and conclude "future re-classification is likely to involve all infrageneric levels, subgenera, sections and series".[64] A further study, using the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA), together with a chloroplast marker, broadly confirmed these findings.[15]

Crocus forms a monophyletic clade, with a basal polytomy of four subclades. The first clade (A) corresponding to section Crocus, but including C. sieberi and several closely related species (originally included in section Nudiscapus series Reticulati). The remaining three clades (B-D) include all the remaining species of section Nudiscapus. Of these, B and C are small, corresponding to series Orientales and Carpetani respectively, with all remaining series in the large D clade. The exception is C. caspius, originally in series Biflori, which segregates in clade B. Thus, although division of the genus into two sections is well supported, no single morphological character defines these two groups. The C. sieberi group are assumed to have lost their prophyll secondarily. Of the series, eight could be shown to be monophyletic; Crocus, Kotschyani and Scardici (section Crocus) and Aleppici, Carpetani, Laevigati, Orientalis and Speciosi (section Nudiscapus). Flowering season did not correspond to molecular groupings and nor did any of the previously used morphological characteristics, indicating a high degree of homoplasy, in which traits are gained or lost independently in different lineages. The remainder of the series could not be supported as natural groupings. Mathew's concept of subspecies status within C. biflorus could not be supported, each being considered a separate species, resulting in the genus having at least 150 species.[15]

A more detailed molecular and morphological study of series Verni (section Crocus) allowed it to be better characterised and circumscribed, as well as the closely related series Longiflori. Series Verni sensu Mathew was found to consist of two groups, the first being C. vernus sensu Mathew and the other consisting of C. etruscus, ilvensis, kosaninii and longiflorus. The taxonomic status of C. vernus had been uncertain for some time, given the observation that the name was more properly applied to C. albiflorus,[34] requiring a new designation of C. neapolitanus for those previously known as C. vernus. Subsequently C. vernus was split into 5 separate species. The incorporation of C. longiflorus into series Verni resulted in making series Longiflori no longer a legitimate taxonomic unit.[60]

In section Nudiscapus, series Reticulati was polyphyletic with species intermingled with series Biflori and Speciosi, requiring a recircumscription, confining Reticulati to 8 species, to obtain monophyly.[65] Among the thereby displaced species, are a number of very closely related taxa, referred to as the Crocus sieberi aggregate, which has been proposed as a new series Sieberi.[29] Other new series, such as Isauri and Lyciotauri, continue to be created out of the Biflori series.[66][67]

Mathew's circumscription of Crocus introduced the rank of subspecies, of which the largest number (14) were those of Crocus biflorus Miller, the type species of series Biflori, a number which continued to grow. Molecular methods identified these as a polyphyletic assemblage rather than closely related subordinate infraspecific taxa. This necessitated a complete taxonomic revision of series Biflori, elevating each subspecies to species status.[61] A similar issue occurs with C. reticulatus sensu Mathew, who created two subspecies, resulting in 9 newly defined species.[65]

Sections and species

The classification of Brian Mathew (1982), as amended in 2009 divides the genus into two sections, further divided by series.[64] The number of series, continues to evolve.

- Section Crocus B.Mathew

Species with a basal prophyll. Type species C. sativus L.

- 6 series

- Section Nudiscapus B.Mathew

Species without a basal prophyll. Type species C. reticulatus Stev. ex Adams

- 9 series

Similarly named species

Some crocus species, known as "autumn crocus", flower in late summer and autumn, during (autumnal) rains, after summer's heat and drought. The name autumn crocus is also often used as a common name for Colchicum,[68] which is not a true crocus but in its own family (Colchicaceae) in the lily order Liliales. The plants are toxic, but have medicinal uses. Colchicum are also known as meadow saffron, though true saffron is not toxic.[69] Crocus species have three stamens while Colchicum species have six;[70] crocus have one style, while Colchicum have three.[71][10]

Some Pulsatilla species are also called "prairie crocus" (previously Anemone patens) or "wild crocus", but they belong to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae).[72][73] Pulsatilla species, which are commonly called pasqueflowers, unlike crocuses have rhizomes, the foliage is covered with long soft hairs, and the flowers are produced on above-ground stems.[74][75]

Etymology

"Crocus", the name of the genus, is Late Middle English (late 14th century) and also denotes saffron. It is derived via Latin crocus from the Greek κρόκος (krokos),[76] which is itself probably a loan word from a Semitic language, related to Hebrew כרכום karkōm,[77] Aramaic ܟܟܘܪܟܟܡܡܐ kurkama, and Arabic كركم kurkum, meaning saffron (Crocus sativus), "saffron yellow" or turmeric (see Curcuma), another yellow dye.[78] The word ultimately traces back to the Sanskrit kunkumam (कुङ्कुमं) for "saffron". The English name is a learned 16th-century adoption from the Latin safranum, but Old English already had croh for saffron, introduced by the Romans.[47][79][80]

Distribution and habitat

Crocuses are distributed from the Mediterranean, from the Iberian peninsula and North Africa, through central and southern Europe, the islands of the Aegean, the Middle East and across central and southwest Asia to Xinjiang in western China, but most species are restricted to Turkey and Asia Minor and the Balkans, with the Balkan Peninsula having the largest number of species (at least 31),[59] forming the centre of diversity, however they are widely introduced.[53][1][81][82] The distribution of species is described over five contiguous areas from west to east (see map).[15]

Habitats range from sea level to as high as subalpine altitudes, and in a wide range of habitats from woodlands to meadows and deserts, often on stony mountain slopes with good drainage.[83][20] The majority of species are native to areas with cold winters and hot summers with little rain, and active growth is typically from fall to mid-spring.[14] The natural habitats of crocus species are threatened by human activities, including urbanization, industrialization, and other land disturbances and recreational uses. They are negatively impacted by uncontrolled gathering and heavy grazing by livestock.[84]

- Crocus alatavicus

- Crocus aleppicus

- Crocus ancyrensis

- Crocus banaticus

- Crocus biflorus

- Crocus cancellatus

- Crocus carpetanus

- Crocus cartwrightianus 'Albus'

- Crocus caspius

- Crocus chrysanthus

'Zwanenburg Bronze' - Crocus corsicus

- Crocus etruscus 'Zwanenburg'

- Crocus goulimyi

- Crocus graveolens

- Crocus hyemalis

- Crocus imperati 'De Jager'

- Crocus kotschyanus

- Crocus laevigatus 'Fontenayi'

- Crocus longiflorus

- Crocus malyi

- Crocus minimus

- Crocus nevadensis

- Crocus nudiflorus

- Crocus olivieri

- Crocus pallasii

- Crocus pulchellus

- Crocus serotinus subsp. clusii

- Crocus serotinus subsp. salzmannii

- Crocus scharojanii

- Crocus tournefortii

- Crocus versicolor

Ecology

The life cycle of Crocus species begins with the seed, germinating to a seedling, and a mature plant in 3–5 years, however seeds may remain dormant in the soil for several years. The germination stages was first described and illustrated by Maw in his 1886 monograph.[47] In its first year, the crocus produces only a single leaf and creates a corm covered by a thin tunic, about 5–8 mm in size, dependent on the species. In the northern hemisphere, the autumnal crocuses flower between September and November. The vernal (spring) crocuses flowering time depends both on climate and habitat, but is usually mid-winter to spring. Leaves may be synanthous (produced during flowering) or hysteranthous (when the flowers wither away).[85] In the summer, with hot and dry conditions the plant becomes dormant, with all the above ground parts dying back. Colder temperatures in winter then activate the corms.[9] Propagation occurs sexually by seed and asexually by small corms, called cormels or cormlets, produced in the axils of the corms (between tunic scales and body of corm).[10] As the fruit capsule ripens, it emerges from the soil at the base of the flowering stem before dehiscing (splitting open) and releasing the seeds.[86] Seed dispersal may be enhanced by ants, at least in species with arillate seeds.[18]

At night and in overcast weather, the perianth closes. The ovary produces nectar which attracts bees (particularly female bumblebees) and Lepidoptera.[10][87]

Pests and diseases

Cultivated plants may have their corms consumed by mice and other rodents,[88] including voles, squirrels,[89] and chipmunks. They are also attacked by mildew, gray mold, botrytis, and fusarium rot. Root rot may also occur, caused by Stromatinia gladioli and Pythium species - the nematode Pratylenchus penetrans may also cause root rot.[90] Viruses that are known to infect Crocus spp include: Potyviruses, especially bean yellow mosaic virus and also tobacco rattle virus, tobaccos necrosis virus, and cucumber mosaic virus.[91] The foliage may experience rot, rust, and scab diseases and be fed upon by aphids, mites, snails, and slugs.[92] The foliage is eaten by hares, rabbits, and deer; the flowers are sometimes removed by birds, including crows, jackdaws, and magpies.[93]

Cultivation

Saffron

The economic importance of the genus is largely dependent on the single species, Crocus sativus, now known only in cultivation.[94] C. sativus is grown for the production of saffron, an orange-red derivative of its dried stigma, and among the most expensive spices in the world.[53] The estimated worldwide production of C. sativus plants is 205 tons.[8] About 180,000 stigmas from 60,000 flowers are required to produce 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) saffron, which sells for about US$10,000 (2018). Modern saffron production is widely cultivated in Kashmir, Iran, Turkey, Afghanistan and the Mediterranean from Spain to Asia Minor.[8] An important center is the eponymous town of Krokos, in the Kozani region of Greece. The saffron product, Krokos Kozanis is a PDO (Protected Designation of Origin).[95][96] Production is largely indigenous and Iran accounts for 65% of global production, covering 72,162 ha.[8]

Saffron is thought to have been used in embalming in Ancient Egypt. It is mentioned in the Old Testament, in the Song of Songs as a precious spice and has featured as a dye and fragrance throughout written history, with mention in the Iliad.[8]

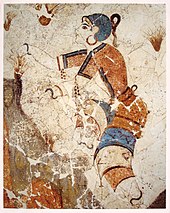

Cultivation and harvesting of C. sativus for saffron was first documented in the Mediterranean, notably on the island of Crete. Frescos showing them are found there at the Bronze Age Minoan site of Knossos, as well as from the comparably aged Akrotiri site on the Aegean island of Santorini,[97][98] and formed an important part of the Minoan economy and culture and had both a sacred role and use as a psychoactive drug and food additive.[99][100][8] Women still gather crocuses in the Akrotiri region.[101]

Horticulture and floriculture

Crocuses were described in Turkish gardens in the early sixteenth century,[102] gathered from the far reaches of the Ottoman Empire,[103] where they were seen by visiting European botanists and explorers, among the first of whom was Pierre Belon who arrived in Constantinople in 1547. The first crocus seen in the Netherlands, where crocus species were not native, were from corms brought to Vienna in 1562 from Constantinople by the Holy Roman Emperor's ambassador to the Sublime Porte, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. A few corms were forwarded to Carolus Clusius at the botanical garden in Leiden.[20] These were almost certainly cultivated varieties rather than wild species.[104] European visitors to Turkey continued to bring back specimens for gardens in their own country. Prominent among the latter were the gardens at Middelburg in the Netherlands. Jehan Somer, a Middelburg merchant, brought back crocuses among his other specimens in 1592, where they attracted the attention not only of Clusius but of the early Dutch flower painters, notably Ambrosius Bosschaert.[105][106] By 1620, new garden varieties had been developed, and featured in contemporary illustrations, such as that of Crispijn van de Passe in his Hortus floridus of 1614.[105] There are accounts of crocus gardens in the seventeenth century, such as the Saffron Garth of Walter Stonehouse at Darfield, Yorkshire.[107]

Crocuses are among the most important ornamental geophytes in the global flower industry,[108] ranking sixth in terms of Dutch bulb production (2003–2008) with 463–668 ha under cultivation.[109] The crocus is one of the most popular flowers found in the garden in the late winter and early spring.[20] About 30 of the species are cultivated, among the most popular being C. chrysanthus, C. flavus, C. sieberi, C. tommasinianus and C. vernus, together with hundreds of cultivars derived from them.[20][8] Both fall and spring blooming crocuses are cultivated for their flowers.[110] Among the first flowers to bloom in spring, their flowering time can vary from fall to the late winter blooming C. tommasinianus; the earliest fall blooming species, C. scharojanii, may flower during the last weeks of July.[111]

The varieties cultivated for decoration in gardens and pots mainly represent six species: C. vernus, C. chrysanthus, C. flavus, C. sieberi, C. speciosus and C. tommasinianus. During the horticulture production year 2009/2010, more than 70 cultivars were grown in Holland, covering an area of 366 hectares; the most common ones were 'Flower Record' and 'King of the Stripes' which accounted for 42 hectares, other species grown included C. chrysanthus, C. tommasinianus, and C. flavus - all are spring blooming plants.[112] But the most commonly grown plants are the Dutch hybrids with large flowers in a rich palette of colors.[113]

Both sexual and asexual means are used to increase the number of plants; seeds and multiplication of corms are the most common means of production, but tissue culture can be used,[114] most commonly for saffron crocus. New corms are formed on top of the older corm which withers away, and cormels are produced from axillary buds.[112] The production of new plants begins with harvested corms in late June to early July, after being graded by corm size the corms are stored around 22 Celsius until early October when they are moved to 17 Celsius until planted later in October and November; flowering occurs in March and the flowers are not removed. Crocuses are also forced to produce flowering plants out of season and the most common species used are C. vernus and C. flavus, and most of the corms used for forcing come from the Netherlands.[115]

Spring flowering types are planted in fall, while fall-blooming types in late summer; typically, the corms are placed 3 to 4 inches deep in well-draining soil in areas with full sun exposure. They do not thrive in heavy clay soils or those that are damp, especially during their summer dormancy period.[116] Commercial crops are produced on raised beds and slopes, to ensure adequate drainage, while horticulturalists often plant on sand beds for the same purpose.[117] Spring flowering types also do well in areas with deciduous trees, where they flower and produce leaves before the trees completely leaf-out. Crocuses are grown in USDA winter zones 3–8.[118] Not all species are hardy in the upper zones; C. sativus is winter hardy in USDA zones 6 through 8, and C. pulchellus is hardy in zones 5 through 8.[92]

Some are suitable for naturalizing in grass, but mowing off the foliage before it turns yellow produces short lived plants. Some crocuses, especially C. tommasinianus and its selected forms and hybrids (such as 'Whitewell Purple' and 'Ruby Giant'), seed prolifically and are ideal for naturalizing. They can, however, become weeds in rock gardens, where they will often appear in the middle of choice, mat-forming alpine plants, and can be difficult to remove. Crocus flowers and leaves are protected from frost by a waxy cuticle; in areas where snow and frost occasionally occur in the early spring, it is not uncommon to see early flowering crocuses blooming through a light late snowfall.[88]

- Field of flowering purple crocuses

- Crocus 'E.A. Bowles',

a C. chrysanthus hybrid - Crocus cultivars

- Purple crocuses with closed flowers

- Crocuses appearing through the snow

Autumn crocus

Autumn-flowering species of crocus that are cultivated include:[85]

|

|

|

C. laevigatus has a long flowering period which starts in late autumn or early winter and may continue into February.

Colchicum autumnale is commonly known as "autumn crocus", but is a member of the plant family Colchicaceae, and not a true crocus (of the family Iridaceae).

Uses

The corms of crocuses have been used as foodstuffs in Syria.[119] The carotenoids found in the styles of Crocus species, particularly C. sativus have been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation, and have led to interest in potential pharmaceutical applications.[15]

Culture

The crocus or krokos has been known since ancient times, and used in decorative arts, such as the Minoan wall paintings in Santorini from ca. 1,600 BC.[97] Representations of the saffron crocus appear frequently in Minoan art[99] and pervade Aegean art from the Early Bronze Age to the Mycenaean period.[120] Theophrastos (4th century BC) described the saffron crocus as being valued as a spice and dye, while Homer compares a sunrise to the flower colour.[121] Saffron coloured robes were much admired by women in antiquity[122] and gave the garment Crocota its name.[123] The oil was also valued as a cosmetic.[124] According to Greek legend Crocus or Krokus (Greek: Κρόκος), was a mortal youth the gods turned into a plant bearing his name, the crocus, after his death caused by his great desire and unfulfilled love for the shepherdess Smilax.[125] Other versions state that as he died three tears fell into the flower becoming its three stigmata.[126][95]

Crocuses occur in many flower paintings, one of the earliest being that of Ambrosius Bosschaert's Composed Bouquet of Spring Flowers (1620). In this painting the cream-colored crocus feathered with bronze at the base of the bouquet reflected varieties on the market at that time. Bosschaert, working from a preparatory drawing to paint his composed piece spanning the whole of spring, exaggerated the crocus so that it passes for a tulip, but its narrow, grass-like leaves give it away.[citation needed]

The crocus is used in many contexts to symbolically denote spring and new beginnings. For instance, it was used as the emblem of the 2019 FIFA U-20 World Cup in Poland to symbolise the emergence of new talent.[127]

Ambrosius Bosschaert c.1620

Crispijn van de Passe, 1614

Grant Wood, 1912

Notes

- ^ As a perfume (ἀρωμάτων) "καὶ πρὸς τούτοις τὸ κρόκινον· βέλτιστος δ’ ἐν Αἰγίνῃ καὶ Κιλικίᾳ (the saffron-perfume; the crocus which produces this is best in Aegina and Cilicia)". He also refers to the crocus as a spice (at 34), the word being interchangeable for either use[23]

- ^ Goldblatt originally described this tribe in 2006,[49] but in 2011 renamed it Ixieae, having discovered that this name had precedence[50]

References

- ^ a b WCLSPF 2022.

- ^ Goldblatt et al 1998, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Meerow 2012, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Goldblatt et al 1998.

- ^ a b c d e Zhao et al 2004.

- ^ Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 297.

- ^ Rudall & Mathew 1990.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kafi et al 2018.

- ^ a b Kerndorff et al 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Mabberley 1997.

- ^ a b Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 307.

- ^ Ali & Mathew 2011.

- ^ Goldblatt et al 1998, pp. 306, 309–310.

- ^ a b Koocheki & Khajeh-Hosseini 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Harpke et al 2013.

- ^ NCBI 2022a.

- ^ NCBI 2022b.

- ^ a b Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 311.

- ^ Mohtashami et al 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2022.

- ^ Serviss et al 2016.

- ^ Caiola & Canini 2010.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1996b.

- ^ Negbi 1989.

- ^ BL 2022.

- ^ Pavord 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Turner 1548.

- ^ Gerard 1597.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kerndorff et al 2016.

- ^ Parkinson 1656.

- ^ l'Obel 1576.

- ^ Besler 1640.

- ^ Maratti 1772.

- ^ a b Peruzzi et al 2013.

- ^ Linnaeus 1753.

- ^ Jussieu 1789.

- ^ a b c Haworth 1820.

- ^ a b c Sabine 1830.

- ^ a b Herbert 1847.

- ^ Lindley 1853, p. 161.

- ^ Baker 1874.

- ^ Bentham & Hooker 1883, p. 693.

- ^ Maw 1886, p. 22.

- ^ APG I 1998.

- ^ Sims 1803.

- ^ Davies 2001.

- ^ a b c d Maw 1886.

- ^ Masclef 1890–1893.

- ^ a b Goldblatt et al 2006.

- ^ Goldblatt & Manning 2011.

- ^ a b Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 312.

- ^ Phillips & Rix 1989, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petersen et al 2008.

- ^ Mathew 1986.

- ^ Rix 2008.

- ^ Mathew 1983.

- ^ Raca et al 2020.

- ^ Ciftci et al 2020.

- ^ a b Randelovic et al 2012.

- ^ a b Harpke et al 2015.

- ^ a b Harpke et al 2016.

- ^ Roma-Marzio et al 2018.

- ^ Harrison & Larson 2014.

- ^ a b Mathew et al 2009.

- ^ a b Harpke et al 2014.

- ^ Kerndorff et al 2014.

- ^ Kerndorff et al 2013.

- ^ Wyman 1986.

- ^ GBIF 2022.

- ^ Armitage 2008, p. 278.

- ^ Bowles 1985, p. 154.

- ^ Runkel & Roosa 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Skelly 1994.

- ^ Wencai & Bartholomew 2004.

- ^ Armitage 2008, p. 843.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1996a.

- ^ Pankhurst & Hyam 1995, p. 134.

- ^ OED 2022.

- ^ Harper 2022.

- ^ Sharifi 2010.

- ^ Flora Italiana 2022.

- ^ Innes 1985.

- ^ Ruksans 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Sevinç Kravkaz & Vurdu 2010.

- ^ a b Jelitto et al 1990.

- ^ Toogood 2019.

- ^ Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 308.

- ^ a b Ruksans 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Heilman 2010, pp. 36–7.

- ^ Ruksans 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Caiola & Faoro 2011.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 2012.

- ^ Ruksans 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Janick et al 2010.

- ^ a b European Commission 2022.

- ^ Negbi 1999.

- ^ a b Trakoli 2021.

- ^ Palyvou 2005, p. 71.

- ^ a b Dewan 2015.

- ^ Betancourt 2007.

- ^ Palyvou 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Willes 2011, p. 72.

- ^ Willes 2011, p. 169.

- ^ Harvey 1976.

- ^ a b Willes 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Goldgar 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Willes 2011, p. 204.

- ^ Kamenetsky & Okubo 2012, p. xv.

- ^ De Hertogh et al 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Viette et al 2015.

- ^ Ruksans 2011, p. 68.

- ^ a b De Hertogh et al 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Bush-Brown et al 1996.

- ^ Rana 2021.

- ^ De Hertogh 1992.

- ^ Tenenbaum 2003.

- ^ Ruksans 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Burrell & Hardiman 2002.

- ^ Goldblatt et al 1998, p. 314.

- ^ Day 2011.

- ^ De Hertogh et al 2012, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Smith 1859, pp. 214, 384, 856, 892.

- ^ Smith 1859, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Smith 1859, p. 1214.

- ^ Lehner & Lehner 2003.

- ^ Schmitz 1850.

- ^ FIFA 2018.

Bibliography

Books

- Betancourt, Philip P. (2007). Introduction to Aegean Art. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press (Institute for Aegean Prehistory). ISBN 978-1-62303-086-5.

- Goldgar, Anne (15 September 2008). Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30130-3.

- Goldblatt, P; Manning, J C; Rudall, P (1998). "Iridaceae: 61 Crocus L.". In Kubitzki, Klaus; Huber, Herbert (eds.). Flowering plants. Monocotyledons: Lilianae (except Orchidaceae). The families and genera of vascular plants. Vol. 3. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 330–331. ISBN 3-540-64060-6.

- Grey-Wilson, C.; Mathew, Brian (1981). Bulbs: the bulbous plants of Europe and their allies. Illustrated by Marjorie Blamey. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-219211-8.

- Heilman, Christine, ed. (2010). Simple Steps to Success: Pests and Diseases (US ed.). NY: Royal Horticultural Society; Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-6996-6.

- Innes, Clive (1985). The World of Iridaceae: A Comprehensive Record. Ashington, Sussex: Holly Gate International. ISBN 978-0-948236-01-3.

- Jelitto, Leo; Schacht, Wilhelm; Fessler, Alfred (1990) [1950 Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart]. "Crocus L. Iridaceae". Hardy Herbaceous Perennials [Die Freiland-Schmuckstauden]. Vol. 1 A–K. trans. Michael E Epp (3rd. ed.). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 168–174. ISBN 978-0-88192-159-5.(Available here at Internet Archive)

- Kamenetsky, Rina; Okubo, Hiroshi, eds. (2012). Ornamental Geophytes: From Basic Science to Sustainable Production. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-4924-8.

- Koocheki, Alireza; Khajeh-Hosseini, Mohammad, eds. (2020). Saffron: Science, Technology and Health. Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-818740-1.

- Lehner, Ernst; Lehner, Johanna (2003) [1960 Tudor Publishing]. "The Crocus". Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants and Trees. Courier Corporation. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-486-42978-6.

- Mathew, Brian (1983) [1982]. The Crocus: A Revision of the Genus Crocus (Iridaceae). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-917304-23-1.

- Negbi, Moshe, ed. (1999). Saffron: Crocus sativus L. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-30366-5.

- Kafi, Muhammad; Kamili, Azra N; Husaini, Amjad N; et al. (2018). "An expensive spice saffron (Crocus sativus L.): A Case Study from Kashmir, Iran and Turkey". In Ozturk, Munir; Hakeem, Khalid Rehman; Ashraf, Muhammad; Ahmad, Muhammad Sajid Aqeel (eds.). Global Perspectives on Underutilized Crops. Springer Nature. pp. 109–150. ISBN 978-3-319-77776-4.

- Palyvou, Clairy (2005). Akrotiri, Thera: An Architecture of Affluence 3,500 Years Old. INSTAP Academic Press (Institute for Aegean Prehistory). ISBN 978-1-62303-068-1.

- Pavord, Anna (2005). The naming of names the search for order in the world of plants. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-59691-965-5.(additional excerpts)

- Ranđelović, Novica; Hill, David A. (1990). The Genus Crocus L. in Serbia. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. ISBN 978-86-7025-117-5.

- Rudall, Paula (1995). Anatomy of the Monocotyledons: VIII Iridaceae. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198545040.

- Sevinç Kravkaz, I.; Vurdu, H. (2010). "Botany of Crocus ancyrensis through Domestication". In Tsimidou, Maria Z.; Polissiou, Moschos; Fernández, José Antonio (eds.). Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Saffron: Forthcoming Challenges in Cultivation, Research and Economics, Krokos, Greece, May 20 2009. ISHS 850. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-90-6605-732-6.

- Runkel, Sylvan T.; Roosa, Dean M. (2009) [1989]. Wildflowers of the Tallgrass Prairie: The Upper Midwest (2nd. ed.). University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-58729-844-8.

- Ruksans, Janis (2011). Crocuses: A Complete Guide to the Genus. Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-60469-106-1.(excerpts available here)

Gardening, horticulture and floriculture

- Armitage, Allan M. (2008). "Crocus". Herbaceous Perennial Plants: A Treatise on their Identification, Culture, and Garden Attributes (3rd ed.). Cool Springs Press. pp. 301–308. ISBN 978-1-61058-380-0.

- Bowles, E. A. (1985) [1924]. A Handbook of Crocus and Colchicum for Gardeners. Waterstone. ISBN 978-0-947752-26-2.(1st ed. Available here at Internet Archive)

- Burrell, C Colston; Hardiman, Lucy (2002). "Encyclopedia of Spring-Blooming Bulbs: Crocus pp. 68–70". In Hanson, Beth (ed.). Spring-blooming Bulbs: An A to Z Guide to Classic and Unusual Bulbs for Your Spring Garden. 21st-Century Gardening, No. 173. Brooklyn Botanic Garden. pp. 52–100. ISBN 978-1-889538-54-9.

- Bush-Brown, Louise; Bush-Brown, James; Irwin, Howard S. (1996) [1939]. "Crocus Spp. and Cvs.". America's Garden Book. New York: Wiley. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-02-860995-9.(Available here at Internet Archive)

- De Hertogh, August (1992) [1980]. "Bulbous and tuberous plants". In Larson, Roy A. (ed.). Introduction to Floriculture (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 197–223. ISBN 978-1-4832-6998-6.

- Hill, Lewis; Hill, Nancy (2012) [2003]. "Crocus". The Flower Gardener's Bible: A Complete Guide to Colorful Blooms All Season Long: 400 Favorite Flowers, Time-Tested Techniques, Creative Garden Designs, and a Lifetime of Gardening Wisdom (10th Anniversary ed.). North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-60342-807-1.

- Mathew, Brian (1987). Flowering Bulbs for the Garden. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-0-600-35175-7.

- Phillips, Roger; Rix, Martyn (1989). The Random House Book of Bulbs. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-72756-9.

- Toogood, Alan, ed. (2019) [1999]. "Crocus". Propagating Plants: How to Create New Plants for Free (Revised ed.). Dorling Kindersley (Penguin). p. 265. ISBN 978-1-4654-9898-4.

- Viette, Andre; Viette, Mark; Heriteau, Jacqueline (2015) [2003]. "Crocus". Mid-Atlantic Getting Started Garden Guide: Grow the Best Flowers, Shrubs, Trees, Vines & Groundcovers (Revised ed.). Cool Springs Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59186-435-6.

- Mathew, Brian (2011) [1984]. "Crocus Linnaeus". In Cullen, James; Knees, Sabina G.; Cubey, H. Suzanne Cubey (eds.). The European Garden Flora, Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and Under Glass. Vol. 1. Alismataceae to Orchidaceae (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 270–277. ISBN 978-0-521-76147-5.

- Willes, Margaret (2011). The Making of the English Gardener: Plants, Books and Inspiration, 1560-1660. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16382-7.

Dictionaries and encyclopedias

- Harper, Douglas (2022). "Crocus". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 11 January 2022., (link note|note=see also Online Etymology Dictionary

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1996). A Greek-English Lexicon 2 vols. Revised by Henry Stuart Jones (9th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-864226-8. Retrieved 10 January 2022., (see also A Greek–English Lexicon)

- Liddell; Scott (1996a). κρόκος , ὁ. Vol. 1. p. 998.

- Liddell; Scott (1996b). ἀρωμα^τ. Vol. 1. p. 254.

- Mabberley, D. J. (1997) [1987]. "Crocus". The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-41421-0.

- Pankhurst, Roger; Hyam, Richard (1995). Plants and their names: a concise dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866189-4.(Available here at Internet Archive)

- Skelly, Carole J. (1994). "Pulsatilla". Dictionary of Herbs, Spices, Seasonings, and Natural Flavorings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-51420-3.

- Tenenbaum, Frances, ed. (2003). "Crocus". Taylor's Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-618-22644-3.

- Wyman, Donald (1986) [1971]. "Crocus". Wyman's Gardening Encyclopedia (2nd. ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-0-02-632070-2.

- Crocus. Oxford University Press. 20 September 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Schmitz, Leonhard (1850). "Crocus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology 2 vols. Vol. I: Abaeus-Dysponteus. London: Taylor and Walton. p. 896.

- Smith, William, ed. (1859). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (2nd. ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Historical sources (chronological)

- Antiquity

- Theophrastus (1916) [4th century BC]. "6. Of the various parts of plants used for perfumes, and of the composition of various notable perfumes, section 27". In Hort, Arthur (ed.). Περὶ φυτῶν ἱστορία: (Περὶ ὀσμῶν; De Odoribus) [Enquiry into Plants: Concerning odours]. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. II. London and New York: William Heinemann and G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 324–489. ISBN 978-0-674-99077-7.(also available here on Penelope)

- 14th century

- BL (2022). "Detailed record for Egerton 747 (ca. 1300–1330)". Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- 16th century

- Turner, William (1548). "Crocus". The Names of Herbes (1881 ed.). London: English dialect society. p. 31.

- l'Obel, Matthias de (1576). "Crocus". Plantarum, seu, Stirpium historia. Cui annexum est aduersariorum volumen (in Latin). Antwerp: Christophori Plantini. p. 53.

- Gerard, John (1597). "80. Of Saffron". The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (1st ed.). London: John Norton. pp. 123–131. (Internet Archive version: also here at Botanicus and here at Biodiversity Heritage Library)

- 17th century

- Besler, Basilius (1640) [1613]. Hortus Eystettensis, sive, Diligens et accurata omnium plantarum, florum, stirpium: ex variis orbis terrae partibus, singulari studio collectarum, quae in celeberrimis viridariis arcem episcopalem ibidem cingentibus, olim conspiciebantur delineatio et ad vivum repraesentatio et advivum repraesentatio opera (in Latin). Nürnberg.

- Parkinson, John (1656). "Crocus saffron". Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, or, A Choise Garden of All Sorts of Rarest Flowers with their Nature, Place of Birth, Time of Flowering, Names, and Vertues to Each Plant, Useful in Physic or Admired for Beauty: To which is Annext a Kitchin-Garden Furnished with All Manner of Herbs, Roots, and Fruits, for Meat or Sauce Used with Us, with the Art of Planting an Orchard... All Unmentioned in Former Herbals. London: Printed by R.N. and are to be sold by Richard Thrale at his shop at the signe of the Cross-Keys at S. Pauls-gate, going into Cheap-side. pp. 160–170.

- 18th century

- Linnaeus, Carl (1753). "Crocus". Species Plantarum: exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas. Vol. 1. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. p. 36., see also Species Plantarum

- Maratti, Giovanni Francesco [in Spanish] (1772). Plantarum Romuleae, et Saturniae in agro Romano existentium: specificas notas describit inventor (in Latin). Rome: Typis Archangeli Casaletti.

- Jussieu, Antoine Laurent de (1789). "Crocus". Genera plantarum: secundum ordines naturales disposita, juxta methodum in Horto regio parisiensi exaratam, anno M.DCC.LXXIV (in Latin). Paris. p. 59. OCLC 5161409.

- 19th century

- Lindley, John (1853) [1846]. The Vegetable Kingdom: or, The structure, classification, and uses of plants, illustrated upon the natural system (3rd. ed.). London: Bradbury & Evans.

- Bentham, G.; Hooker, J.D. (1883). "Crocus". Genera plantarum ad exemplaria imprimis in herbariis kewensibus servata definita. Vol. III Part II. London: L Reeve & Co. p. 693.

- Maw, George (1886). A monograph of the genus Crocus. With an appendix on the etymology of the words crocus and saffron by C.C. Lacaita. London: Dulau and Co.

- Nature (February 1887). "The Crocus". Nature (Review). 35 (902): 348–349. Bibcode:1887Natur..35..348.. doi:10.1038/035348a0. S2CID 4091523.

- Masclef, Amédée (1890–1893). Atlas des plantes de France 3 vols. Vol. 3. p. 328.

Chapters

- De Hertogh, August A; van Scheepen, Johan; Le Nard, Marcel; Okubo, Hiroshi; Kamenetsky, Rina (2012). Globalization of the flower bulb industry. CRC Press. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9781439849248., in Kamenetsky & Okubo (2012)

- Meerow, Alan W (2012). Taxonomy and phylogeny. CRC Press. pp. 17–56. ISBN 9781439849248., in Kamenetsky & Okubo (2012)

- Okubo, Hiroshi; Sochacki, Dariusz (2012). Botanical and horticultural aspects of major ornamental geophytes: II Crocus. CRC Press. pp. 79–82. ISBN 9781439849248., in Kamenetsky & Okubo (2012)

Articles

- Caiola, Maria Grilli; Canini, Antonella (2010). "Looking for Saffron's (Crocus sativus L.) Parents" (PDF). Functional Plant Science and Biotechnology. 4 (2): 1–14.

- Caiola, Maria Grilli; Faoro, Franco (2011). "Latent virus infections in Crocus sativus and Crocus cartwrightianus". Phytopathologia Mediterranea. 50 (2): 175–182. JSTOR 26458691.

- Challenger, Charlie (March 1986). "The Pleasures of Crocus". The New Zealand Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture). 1 (1): 12–17.

- Davies, Kevin L. (2001). "The life and work of Sydenham Edwards FLS, Welshman, Botanical and Animal Draughtsman 1768-1819". Minerva - The Journal of Swansea History. 9: 30–58.

- Day, Jo (2011). "Crocuses in context: A Diachronic Survey of the Crocus Motif in the Aegean Bronze Age". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 80 (3): 337. doi:10.2972/hesperia.80.3.0337. S2CID 165105395.

- Dewan, Rachel (2015). "Bronze Age Flower Power: The Minoan Use and Social Significance of Saffron and Crocus Flowers" (PDF). Chronika. 5: 42–55.

- Harrison, Richard G.; Larson, Erica L. (1 December 2014). "Hybridization, Introgression, and the Nature of Species Boundaries". Journal of Heredity. 105 (S1): 795–809. doi:10.1093/jhered/esu033. PMID 25149255.

- Harvey, John H. (1976). "Turkey as a Source of Garden Plants". Garden History. 4 (3): 21–42. doi:10.2307/1586521. ISSN 0307-1243. JSTOR 1586521.

- Janick, Jules; Daunay, Marie Christine; Paris, Harry (November 2010). "Horticulture and Health in the Middle Ages: Images from the Tacuinum Sanitatis". HortScience. 45 (11): 1592–1596. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.45.11.1592. S2CID 86510163.

- Kandeler, R.; Ullrich, W. R. (25 November 2008). "Symbolism of plants: examples of European-Mediterranean culture presented with biology and history of art: JANUARY: Crocus". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (1): 6–8. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern360. PMID 19213723.

- Mathew, Brian (1986). "George Maw and his monograph". The Kew Magazine. 3 (4): 186–189. JSTOR 45066517.

- Mohtashami, Leila; Amiri, Mohammad Sadegh; Ramezani, Mahin; Emami, Seyed Ahmad; Simal-Gandara, Jesus (November 2021). "The genus Crocus L.: A review of ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology". Industrial Crops and Products. 171: 113923. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113923.

- Negbi, Moshe (May 1989). "Theophrastus on geophytes". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 100 (1): 15–43. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1989.tb01708.x.

- Pastor-Férriz, Teresa; De-los-Mozos-Pascual, Marcelino; Renau-Morata, Begoña; Nebauer, Sergio G.; Sanchis, Enrique; Busconi, Matteo; Fernández, José-Antonio; Kamenetsky, Rina; Molina, Rosa V. (3 March 2021). "Ongoing Evolution in the Genus Crocus: Diversity of Flowering Strategies on the Way to Hysteranthy". Plants. 10 (3): 477. doi:10.3390/plants10030477. PMC 7999489. PMID 33802494.

- Rix, Alison (May 2008). "George Maw, Joseph Hooker and the genus Crocus". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 25 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8748.2008.00616.x.

- Rudall, Paula; Mathew, Brian (1990). "Leaf Anatomy in Crocus (Iridaceae)". Kew Bulletin. 45 (3): 535–544. Bibcode:1990KewBu..45..535R. doi:10.2307/4110516. JSTOR 4110516.

- Sharifi, G. (January 2010). "Etymology, history and application of saffron (Crocus sativus l.) in ancient Iran". Acta Horticulturae (850): 309–314. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2010.850.53.

- Trakoli, Anna (16 June 2021). "Minoan Art, The 'Saffron Gatherers', c1650 BC". Occupational Medicine. 71 (3): 124–126. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqab019.

- Rana, Yudhvir (20 June 2021). "Himachal Pradesh set for commercial cultivation of saffron". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

Phylogeny and taxonomy

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998). "An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 85 (4): 531–553. doi:10.2307/2992015. JSTOR 2992015.

- Aghighiravan, Fatemeh; Shokrpour, Majid; Nazeri, Vahideh; Naghavi, Mohammad Reza (July 2019). "Phylogenetic Assessment of Some Species of Crocus Genus Using DNA Barcoding". Journal of Genetic Resources. 5 (2). doi:10.22080/jgr.2019.2408.

- Çiftçi, Almila; Harpke, Doerte; Mollman, Rachel; Yildirim, Hasan; Erol, Osman (6 April 2020). "Notes on Crocus L. Series Flavi Mathew (Iridaceae) and a new species with unique corm structure". Phytotaxa. 438 (2): 65–79. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.438.2.1. S2CID 216439891.

- Goldblatt, Peter (1990). "Phylogeny and classification of Iridaceae". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 77 (4): 607–627. doi:10.2307/2399667. JSTOR 2399667.

- Goldblatt, P. (2000). "Phylogeny and Classificationof the Iridaceae and the Relationships of Iris". Annali di Botanica. 58: 13–28. ISSN 2239-3129.

- Goldblatt, Peter; Davies, Jonathan; Manning, John; van der Bank, Michelle; Savolainen, Vincent (2006). "Phylogeny of Iridaceae Subfamily Crocoideae Based on a Combined Multigene Plastid DNA Analysis". Aliso. 22 (1): 399–411. doi:10.5642/aliso.20062201.32.

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J. C. (13 December 2011). "Systematics of the southern African genus Ixia (Iridaceae). 3. Sections Hyalis and Morphixia". Bothalia. 41 (1): 83–134. doi:10.4102/abc.v41i1.35. S2CID 84534897.

- Harpke, Dörte; Meng, Shuchun; Rutten, Twan; Kerndorff, Helmut; Blattner, Frank R. (March 2013). "Phylogeny of Crocus (Iridaceae) based on one chloroplast and two nuclear loci: Ancient hybridization and chromosome number evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 66 (3): 617–627. Bibcode:2013MolPE..66..617H. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.10.007. PMID 23123733.

- Harpke, Dörte; Peruzzi, Lorenzo; Kerndorff, Helmut; Karamplianis, Theophanis; Constantinidis, Theophanis; Ranđelović, Vladimir; Ranđelović, Novica; Jušković, Marina; Pasche, Erich; Blattner, Frank R. (2014). "Phylogeny, geographic distribution, and new taxonomic circumscription of the Crocus reticulatus species group (Iridaceae)". Turkish Journal of Botany. 38: 1182–1198. doi:10.3906/bot-1405-60.

- Harpke, Dörte; Carta, Angelino; Tomović, Gordana; Ranđelović, Vladimir; Ranđelović, Novica; Blattner, Frank R.; Peruzzi, Lorenzo (January 2015). "Phylogeny, karyotype evolution and taxonomy of Crocus series Verni (Iridaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 301 (1): 309–325. Bibcode:2015PSyEv.301..309H. doi:10.1007/s00606-014-1074-0. S2CID 18507508.

- Harpke, Dörte; Kerndorff, Helmut; Pasche, Erich; Peruzzi, Lorenzi (11 May 2016). "Neotypification of the name Crocus biflorus Mill. (Iridaceae) and its consequences in the taxonomy of the genus". Phytotaxa. 260 (2): 131–143. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.260.2.3.

- Kerndorff, Helmut; Pasche, Erich; Harpke, Dörte (2014). "Crocus isauricus Siehe ex BowleS (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae) and its relatives" (PDF). Stapfia. 101: 3–18.

- Kerndorff, Helmut; Pasche, Erich; Harpke, Dörte (2015). "The Genus Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae): Lifecycle, Morphology, Phenotypic Characteristics, and Taxonomical Relevant Parameters" (PDF). Stapfia. 103: 27–65.

- Kerndorff, Helmut; Pasche, Erich; Harpke, Dörte (2015a). "Crocus lyciotauricus Kerndorff & Pasche (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae) and its relatives" (PDF). Stapfia. 103: 67–80.

- Kerndorff, Helmut; Pasche, Erich; Harpke, Dörte (2016). "The Genus Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae): Taxonomical Problems and How to Determine a Species Nowadays?" (PDF). Stapfia. 105: 42–5o.

- Mathew, Brian; Petersen, Gitte; Seberg, Ole (2009). "A reassessment of Crocus based on molecular analysis". The Plantsman. New Series. 8 (1): 50–57.

- Nemati, Zahra; Blattner, Frank R.; Kerndorff, Helmut; Erol, Osman; Harpke, Dörte (October 2018). "Phylogeny of the saffron-crocus species group, Crocus series Crocus (Iridaceae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 127: 891–897. Bibcode:2018MolPE.127..891N. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.06.036. PMID 29936028. S2CID 49409790.

- Peruzzi, Lorenzo; Carta, Angelino; Garbari, Fabio (22 October 2013). "Lectotypification of the name Crocus sativus var. vernus L. (Iridaceae) and its consequences within Crocus ser. Verni". Taxon. 62 (5): 1037–1040. doi:10.12705/625.7.

- Petersen, Gitte; Seberg, Ole; Thorsøe, Sarah; Jørgensen, Tina; Mathew, Brian (2008). "A Phylogeny of the Genus Crocus (Iridaceae) Based on Sequence Data from Five Plastid Regions". Taxon. 57 (2): 487–499. doi:10.2307/25066017. JSTOR 25066017.

- Roma-Marzio, Francesco; Harpke, Doerte; Peruzzi, Lorenzo (9 May 2018). "Rediscovery of Crocus biflorus var. estriatus (Iridaceae) and its taxonomic characterisation". Italian Botanist. 6: 23–30. doi:10.3897/italianbotanist.6.28729. S2CID 91370762.

- Serviss, Brett E.; Peck, James H.; Benjamin, Kristen R. (2016). "Crocus flavus: a new genus and species of non-native Iridaceae for the Arkansas (U.S.A.) flora". Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 10 (2): 513–516. JSTOR 44858594.

- Yilmaz, Aykut (1 June 2021). "The Evaluations and Comparisons of Nuclear and Chloroplast DNA Regions Based on Species Identification and Phylogenetic Relationships of Crocus L. Taxa". Journal of the Institute of Science and Technology. 11 (2): 1504–1518. doi:10.21597/jist.791414. S2CID 234849841.

Novel taxa

- Harpke, Dörte; Kerndorff, Helmut; Raca, Irena; Pasche, Erich (23 September 2017). "A New Serbian Endemic Species Of The Genus Crocus (Iridaceae)". Biologica Nyssana. 8 (1): 7–13. doi:10.5281/zenodo.962907.

- Kerndorff, H; Pasche, E (31 July 1997). "Zwei bemerkenswerte Taxa des Crocus biflorus-Komplexes (Iridaceae) aus der Nordosttürkei" [Two remarkable taxa of the Crocus biflorus complex (Iridaceae) from northeastern Turkey] (PDF). Linzer Biologische Beitraege (in German) (1): 591–600.

- Kerndorff, H; Pasche, E (2011). "Two new taxa of Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae) from Turkey" (PDF). Stapfia. 95: 2–5.

- Kerndorff, H; Pasche, E; Harpke, D; Blattner, FR (2012). "Seven New Species of Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae) from Turkey" (PDF). Stapfia. 97: 3–16.

- Kerndorff, H; Pasche, E; Blattner, FR; Harpke, D (2013). "Fourteen New Species of Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae) from West, South-West and South-Central Turkey" (PDF). Stapfia. 99: 145–158.

- Miljković, Milica; Ranđelović, Vladimir; Harpke, Dörte (9 June 2016). "A new species of Crocus (Iridaceae) from southern Albania (SW Balkan Peninsula)". Phytotaxa. 265 (1): 39–49. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.265.1.3.

- Papanicolaou, K.; Zacharof, E. (17 January 1980). "Crocus in greece new taxa and chromosome numbers". Botaniska Notiser. 133 (2): 155–164.

- Peruzzi, Lorenzo; Carta, Angelino (February 2011). "Crocus ilvensis sp. nov. (sect. Crocus, Iridaceae), endemic to Elba Island (Tuscan Archipelago, Italy)". Nordic Journal of Botany. 29 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2010.01023.x.

- Raca, Irena; Harpke, Dörte; Shuka, Lulëzim; Ranđelović, Vladimir (19 October 2020). "A new species of Crocus ser. Verni (Iridaceae) with 2 n = 12 chromosomes from the Balkans". Plant Biosystems. 156: 36–42. doi:10.1080/11263504.2020.1829735. S2CID 225006706.

- Ranđelović, Novica; Ranđelović, Vladimir; Hristovski, Nikola (April 2012). "Crocus jablanicensis (Iridaceae), a new species from the Republic of Macedonia, Balkan Peninsula". Annales Botanici Fennici. 49 (1–2): 99–102. doi:10.5735/085.049.0116. ISSN 0003-3847. JSTOR 23728141. S2CID 84237883.

- Schneider, Ingo (2014). "Crocus brachyfilus (Iridaceae), a new species from southern Turkey". Willdenowia. 44 (1): 45–50. doi:10.3372/wi.44.44107. ISSN 0511-9618. JSTOR 24750912. S2CID 86431711.

Historical accounts

- Baker, John Gilbert (1874). "A Classified Synonymic List of all the Known Crocuses, with their Native Countries, and References to the Works where they are Figured". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society of London. 4 (14): 111–119.

- Curtis, William (1787). "Crocus vernus". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 2: T45.

- Haworth, Adrian (1820). "On the Cultivation of Crocuses, with a short Account of the different Species known at present. February 7, 1809". Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London. 1. M. Bulmer & Co.: 122–139.

- Herbert, William (1847). "A History of the Species of Crocus". The Journal of the Horticultural Society of London. 2: 249–293.

- Sabine, Joseph (1830). "An Account and Description of the Species and most remarkable Varieties of Spring Crocuses, cultivated in the Garden of the Horticultural Society. January 6, 1829". Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London. 7: III: 419–432, IV: 433–498.

- Sims, John (1803). "Crocus susianus. Cloth of Gold Crocus". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 18: T652.

Websites

- European Commission (2022). "Krokos Kozanis PDO". Food, Farming, Fisheries: EU Quality Food and Drink. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Elenco delle specie - Genere: Crocus - Famiglia: Iridaceae". Flora Italiana. 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- Harris, Stephen (2022). "Crocus species (Iridaceae)". Oxford University Plants 400. Department of Plant Sciences, Oxford University. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- FIFA (14 December 2018). "Emblem and match schedule for Poland 2019 unveiled". Tournaments. FIFA. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Porcher, Michel H. (25 June 2013). "Sorting Crocus names". Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database. Department of Agriculture and Food Systems, Melbourne School of Land and Environment, University of Melbourne. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Sözen, İbrahim (2022). "The Country Of Crocuses". Crocusmania (in Turkish). Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Boland, Todd (20 September 2008). "Crocus to Brighten the Spring Garden". Dave's Garden. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- NCBI (2022a). "CID 5281233, Crocin". PubChem. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- NCBI (2022b). "CID 5281232, Crocetin". PubChem. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Distribution area of the genus Crocus subdivided into five different geographic regions (A-E)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (Map). 66 (3): 617–627: Supplementary material. March 2013.

Organisations and collections

- IBS. "Crocus". International Bulb Society. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- PBS (5 March 2021). "Crocus". Photographs and Information. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Bowles (2022). "Crocus Collection". E. A. Bowles of Myddelton House Society. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Lonsdale, John. "Crocus". The Lonsdale Collection. The Alpine Garden. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Lonsdale, John (2022). "Crocuses". The Lonsdsale Garden. Edgewood Gardens. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Goode, Tony (2022). "Crocus Pages". Alpine Garden Society. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

Databases and flora

- "Crocus". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Flora of China

- Zhao, Yu-tang; Noltie, Henry J.; Mathew, Brian F. (2004). "Crocus Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 36. 1753". p. 313. Retrieved 6 January 2022., in Flora of China online vol. 24

- Wencai, Wang; Bartholomew, Bruce (2004). "Pulsatilla Miller, Gard. Dict. Abr., ed. 4. [1136]. 1754". p. 329. Retrieved 10 January 2022., in Flora of China online vol. 6

- Ali, S. I.; Mathew, Brian (2011). "Crocus L." Flora of Pakistan. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- GBIF. "Crocus L." Retrieved 9 January 2022.