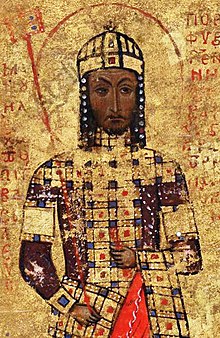

Constantine Angelos

Constantine Angelos | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1093 |

| Died | after 1166 |

| Allegiance | Byzantine Empire |

| Years of service | c. 1149–1166 |

| Wars | Byzantine–Hungarian wars, Byzantine–Norman wars |

| Spouse(s) | Theodora Komnene |

| Relations | John Doukas and Andronikos Doukas Angelos (sons) |

Constantine Angelos (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος Ἄγγελος; c. 1093 – after 1166) was a Byzantine aristocrat who married into the Komnenian dynasty and served as a military commander under Manuel I Komnenos, serving in the western and northern Balkans and as an admiral against the Normans. He was the founder of the Angelos dynasty, which went on to rule the Byzantine Empire in 1185–1204 and found and rule the Despotate of Epirus (1205–1318) and the Empire of Thessalonica (1224–1242/46).

Life

Constantine was born in c. 1093 to an obscure family of the local aristocracy of Philadelphia.[1] The family's surname, "Angelos", is commonly held to have derived from the Greek word for "angel", but such an origin is rarely attested in Byzantine times, and it is possible but unlikely that their name instead derives from A[n]gel, a district near Amida in Upper Mesopotamia.[2] The historian Suzanne Wittek-de Jongh suggested that Constantine was the son of a certain patrikios Manuel Angelos, whose possessions near Serres were confirmed by a chrysobull of Emperor Nikephoros III (r. 1078–1081), but this is considered unlikely by other scholars,[3] even though Angelos possessions in the area of Serres and Zichne are clear in the sources until XIV century.[4]

Despite his lowly (outside the close imperial circle) origin, Constantine was reportedly brave and exceedingly beautiful,[2] and managed to win the heart of Theodora Komnene (born 1097), the fourth daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) and Irene Doukaina. Theodora had already been married once, to Constantine Kourtikes, but her husband had died without having had children.[5] The marriage probably took place in c. 1122, certainly after the death of Alexios I; Empress Irene apparently disapproved of it, and it seems to have soured her relations with Theodora, who is listed last and with the least favourable provisions in the typikon that Irene granted to the Kecharitomene Monastery.[6]

Constantine's marriage lifted him out of obscurity, and gave him the title of sebastohypertatos,[7] one of the highest Byzantine dignities, given to the husbands of an emperor's younger daughters. The rank may have been created specifically for Constantine, as he is one of the first two recorded holders.[8] His activities during the reign of Theodora's brother John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143) are unknown, but he, like his brothers, Nicholas, John, and Michael, enjoyed the favour of John's son and successor, Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180).[9] Thus on 26 February 1147 he participated in the church council of Blachernae that deposed Patriarch Cosmas II Attikos, being ranked in fourth place behind the heir-apparent, despotes Bela-Alexios, the Caesar John Rogerios Dalassenos, and the panhypersebastos Stephen Kontostephanos.[10][11][12] In summer 1149, he accompanied Emperor Manuel in his campaign in Dalmatia. After Manuel captured the fortress of Razon, Constantine was left to guard the area, and launched an expedition into the Nishava valley.[13][10][14]

In 1154, as Manuel prepared for war with William I of Sicily, he gave his uncle command of the Byzantine fleet and ordered him to proceed to Monemvasia, where to await further reinforcements. Constantine, however, was persuaded by his astrologers that if he attacked the Sicilians he would win. Disobeying the Emperor's orders, he proceeded to intercept a far larger Sicilian fleet returning from a raid against Fatimid Egypt. In the ensuing engagement, the Byzantines were defeated and most of their ships were captured. His brother Nicholas managed to escape with a handful of ships, but Constantine was captured and princely imprisoned in Palermo for few years until 1158, when Manuel concluded a peace treaty with William.[15]

In June or July 1166, Emperor Manuel charged him and Basil Tripsychos with repairing and strengthening the fortifications of Zemun, Belgrade, and Niš, and generally strengthen Byzantium's frontier with Hungary along the middle Danube. As part of this process, he organized the resettlement of Braničevo.[16] The date of his death is unknown; his wife possibly predeceased him, as she is last mentioned in 1136.[17]

Children

Through his marriage with Theodora, Constantine had seven children, three sons and four daughters.[13][18] Through his sons, Constantine was the progenitor of the Angelos dynasty, which produced three Byzantine emperors in 1185–1204, as well as the "Angelos Komnenos Doukas" dynasty that ruled over Epirus and Thessalonica in the 13th–14th centuries.[2][3]

- John Doukas (c. 1125/27 – c. 1200), had several children by one or two marriages, and a bastard son. The latter, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (r. 1205–1214/15), would go on to found the Despotate of Epirus, and was succeeded by his half-brothers.[19]

- Maria Angelina (born c. 1128/30), married Constantine Kamytzes, by whom she had a number of children, including Manuel Kamytzes.[20]

- Alexios Komnenos Angelos (born c. 1131/32), married and fathered one son.[21]

- Andronikos Angelos Doukas (c. 1133 – before September 1185), married Euphrosyne Kastamonitissa, by whom he had nine children, including emperors Isaac II Angelos (r. 1185–1195, 1203–1204) and Alexios III Angelos (r. 1195–1203).[22]

- Eudokia Angelina (born c. 1134), married Basil Tzykandeles Goudeles. The couple had no children.[23]

- Zoe Angelina (born c. 1135), married Andronikos Synadenos. The couple had several children, whose names are unknown.[24]

- Isaac Angelos Doukas (born c. 1137), married and had at least four children,[25] including the unsuccessful usurper Constantine Angelos Doukas and the wife of Basil Vatatzes.

Identity

Beginning with Du Cange, many earlier historians distinguished between two persons of this name, since the sources record that a minor noble named Constantine Angelos, from Philadelphia, married the fourth daughter of Alexios I Komnenos and received the title of pansebastohypertatos, whereas the Constantine Angelos, uncle of Manuel I and active during the latter's reign, is recorded in the sources as a sebastohypertatos. However, in 1961 Lucien Stiernon demonstrated that the two persons are in fact the same, with pansebastohypertatos being merely a rhetorical augmentation of the proper title.[26]

References

- ^ Varzos 1984, p. 260.

- ^ a b c ODB, "Angelos" (A. Kazhdan), pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Varzos 1984, pp. 260–261 (note 6).

- ^ https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/4063/1/Malatras13PhD(1).pdf

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 260–261, esp. note 9.

- ^ Varzos 1984, p. 261.

- ^ Stiernon 1965, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 260–262, esp. note 6.

- ^ a b Varzos 1984, p. 262.

- ^ Stiernon 1961, pp. 274, 277.

- ^ Magdalino 2002, p. 503.

- ^ a b Stiernon 1961, p. 274.

- ^ Popović 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Varzos 1984, p. 263.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Varzos 1984, p. 264.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 641–649.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 650–653.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 654–655.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 656–662.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 663–667.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 668–672.

- ^ Varzos 1984, pp. 673–674.

- ^ Stiernon 1961, pp. 273–283.

Sources

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002) [1993]. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1.

- Popović, Marko (1999). Tvrđava Ras [The Fortress of Ras] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Archaeological Institute. ISBN 9788680093147.

- Stiernon, Lucien (1961). "Notes de prosopographie et de titulature byzantines: Constantin Ange (pan)sébastohypertate". Revue des études byzantines (in French). 19: 273–283. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1961.1262.

- Stiernon, Lucien (1965). "Notes de titulature et de prosopographie byzantines. Sébaste et Gambros". Revue des études byzantines (in French). 23: 222–243. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1965.1349.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784634.