Compton Verney House

Compton Verney House (grid reference SP312529) is an 18th-century country mansion at Compton Verney near Kineton in Warwickshire, England. It is located on the west side of a lake north of the B4086 about 12 miles (19 km) north-west of Banbury. Today, it is the site of the Compton Verney Art Gallery.

Overview

The building is a Grade I listed house built in 1714 by Richard Verney, 11th Baron Willoughby de Broke. It was first extensively extended by George Verney, 12th Baron Willoughby de Broke in the early 18th century and then remodelled and the interiors redesigned by Robert Adam for John Peyto-Verney, the 14th baron, in the 1760s. It is set in more than 120 acres (0.49 km2) of parkland landscaped by Lancelot "Capability" Brown in 1769.

The house and its 5,079-acre (20.55 km2) estate was sold by Richard Greville Verney, the 19th baron, in 1921 to soap magnate Joseph Watson who was elevated to the peerage as 1st Baron Manton of Compton Verney only two months before his death in March 1922 from a heart attack whilst out hunting with the Warwickshire Foxhounds at nearby Upper Quinton. George Miles Watson, 2nd Baron Manton sold the property to Samuel Lamb. It was requisitioned by the army during World War II and became vacant when the war ended.

In 1993 it was bought in a run-down state by the Peter Moores Foundation, a charity supporting music and the visual arts established by former Littlewoods chairman Sir Peter Moores. The property was restored to a gallery capable of hosting international exhibitions. Compton Verney Art Gallery is now run by Compton Verney House Trust, a registered charity.[1]

The collections include Neapolitan art from 1600 to 1800; Northern European medieval art from 1450 to 1650; British portraits including paintings of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and Edward VI and works by Joshua Reynolds; Chinese bronzes including objects from the Neolithic and Shang periods; British folk art; and the Enid Marx / Margaret Lambert Collection of folk art from around the world which inspired the textile designs of 20th century artist Enid Marx.[2]

History

Medieval

According to William Dugdale there was a manor-house built at Compton Verney in about 1442. In 1656 William Dugdale wrote in his Antiquities of Warwickshire:

“Richard Verney Esquire (afterward Knight)... built a great part of the House, as it now standeth, wherein, besides his own Armes with matches, he then set up...towards the upper end of the Hall, the Armes of King Henry the Sixth.“[3]

Tudor and Stuart

The house was further extended in the late sixteenth century, following the marriage of Sir Richard Verney (1536–1630) to Margaret, daughter of Sir Fulke Greville (1535–1606). Richard inherited her family estates and claims to the barony of Willoughby de Broke.

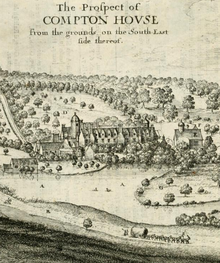

Very little is known about this early house at Compton Verney. A drawing by Wenceslaus Hollar of about 1655, published by William Dugdale, shows a great hall, a long south wing with gabled dormer windows and chimneys looking down to the lake. It had octagonal turrets at either end, kitchens to the left (south west) and a chapel. The first surviving inventory of the house, which dates from the middle of the English Civil War in 1642, describes a house of thirty rooms (including a hall, two parlours, seventeen bedrooms, an armoury and study as well as servants’ quarters and outbuildings), furnished with velvet, tapestry and pictures to a total value of £900. A silk and wool embroidery showing Lucretia’s Banquet may have been one of the original pieces hanging in the Great Hall from this period. Records show that this was sold in 1913 to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[4] Richard and Margaret's only son, Greville Verney (c. 1586 – 1642), the 7th Baron Willoughby de Broke and 15th Baron Latimer held tenure of Compton Verney from his father's death in 1630 until his own death in 1642.

At this time the house was passed to Greville Verney (1619–1648). Upon his death, tenure then passed to Sir Greville Verney (1649–1668) and then on to William Verney (1668–1683) the 10th Baron Willoughby de Broke who died aged 15 with no heir. The title went into abeyance until William's great-uncle Richard Verney (1621–1711), who inherited the estate in 1683, decided to exert his claim to the barony. In 1695 the House of Lords accepted the claim and Richard Verney became the 11th Baron Willoughby de Broke.[5][6]

Georgian

In 1711, George Verney (1661–1728) the 12th Baron Willoughby de Broke, inherited the estate and decided to rebuild the house and re-landscape the gardens. This was a period when medieval houses were being remodelled in the classical style, and new country seats such as the Duke of Marlborough’s Blenheim Palace in nearby Woodstock were being built. George commissioned an extensive reconstruction of the earlier house, whilst preserving much of the plan of the original building.

The new design that was commissioned – the basis of the house which we see today – has been convincingly attributed by architectural historian Richard Hewlings to the Oxford master-mason John Townesend (1678–1742) and his son William, who had worked at Blenheim Palace and at many of the new college buildings being built in Oxford.

The basic layout of Compton Verney in the 1730s can be reconstructed from the surviving evidence, which includes two inventories dating from this period. It was a courtyard house, entered from the east (as today), through an archway with a cupola in the now-lost east wing. The main apartments were in the west and south wings, with the servants’ quarters on the north side where the service buildings were. The west wing was dominated by the Great Hall, which probably occupied the same site as the original medieval Hall built in the 1440s. The Great Staircase (now lost) led up from the Hall to the main apartments above.[4][7]

The Stable Block

Stables were built to the north of the house in 1735 by architect James Gibbs; these can still be seen today. Extensive formal gardens were also added to the north and south, and the main approach to the house ran east to west, with an ornamental canal on the west lawn.

A visitor, John Loveday of Caversham, described the house in 1735, writing:

Just on the right of the road between Little Keinton [sic] and Wellsburn [sic] is the seat of the Hon. Mr Verney ... It stands low and is built of Stone; the front is towards the Garden and has 11 Windows ... Below there is a handsome Gallery or Dancing Room... The Gardens, with the room taken up by the house contain 20 Acres. The Gardens rise up an hill, and are well-contrived for Use and Convenience. There are Views down to a Pond; of these Ponds there are 4 in a string, which make a mile in length.[8]

After both sons died, the estate was inherited by George’s great-nephew, John Peyto Verney, (1738–1816) subsequently 14th Baron, who was also fortunate enough to inherit the neighbouring estate of Chesterton, thus raising the family’s income to a substantial £4,000 a year. This additional income and his marriage in 1761 to the sister of Lord North (from nearby Wroxton Abbey, Oxfordshire) may have been what encouraged John Peyto Verney to improve the estate and completely remodel the house as George had done.[4]

Robert Adam remodelled

John commissioned the prominent Scottish neoclassical architect, Robert Adam,[9] to propose alterations to Compton Verney. Adam’s proposed remodelling was much more extensive than anything that had taken place before. His drawings of the ground, first and attic storeys show what was to be retained from the original building and what was demolished. Three of the four sides of the original courtyard house (the east, north and south wings) were to be torn down, and Adam proposed the addition of a portico on the new east front and the reconstruction of the north and south wings, giving the house its present U-shape.

The building work for Adam's alterations was carried out from about 1762–1768, supervised by the Warwick architect and mason, William Hiorn, who was also employed locally at Charlecote House and Stoneleigh Abbey. The stone came from the estate and the surrounding local quarries of Warwick, Hornton, Gloucester and Painswick. The most important changes include the removal of the Great Staircase on the west front and its replacement by a Saloon with pairs of columns, plus alterations to the Hall, as well as the creation of an attic storey above it. Adam also added a library and octagonal study to the south wing and adapted the brewhouse and bakery to the north of the house.

The floor plans of the house were published in the fifth volume of Vitruvius Britannicus in 1771 by Colen Campbell, and show various differences from Adam’s drawings, some of which suggest that some of the Baroque interiors had been left as they were. Robert Adam was often responsible for the interior decoration as well as the architectural design of his buildings. However, at Compton Verney he designed the decoration of only a few rooms, including the Hall and the Saloon. The rest were decorated by local craftsmen using their own pattern-book designs.

His drawing for the decoration of the Hall in the Victoria & Albert Museum shows three large plaster picture frames placed high on the walls that originally contained large landscape paintings with classical ruins. These landscapes were painted by the Venetian artist and favoured collaborator of Robert Adam, Antonio Pietro Francesco Zucchi (1726–1795). They were removed from the house and sold at a later date, and only the plaster frames remain. It is this period in the history of the house that is captured in the famous painting by the artist Johann Zoffany, now owned by the J.Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The painting shows John, 14th Baron and his family in the breakfast room on the ground floor at Compton Verney.[10] Although Adam’s work on the mansion was completed in 1769, building work continued on the other buildings at Compton Verney until the 1780s and it was during this period that the grounds were re-landscaped. In 1769/1770 the ‘Green House’ (which no longer survives) was constructed, and in 1771/1772 the Ice-House and ‘Cow House’ were finished.[11]

Lancelot 'Capability' Brown at Compton Verney

In 1769, landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown was employed to lay out the grounds in keeping with the new taste for more naturalistic landscape. He eliminated all trace of the earlier formal gardens, including the canal on the west front and the avenues running east to west. These were replaced with grassland and trees, with the planting of cedars and over 2,200 oak and ash saplings. Brown also turned the lakes into a single expanse of water by removing the dam between the Upper Long Pool and the Middle Pool to make way for his Upper Bridge.[12][13]

The Ice House

The Ice House was built in 1772 by ‘Capability’ Brown during the extensive remodelling. An Ice House was a ‘must have’ accessory of the day amongst leading gentry, with growing demand for refrigerated food, sorbets and ice creams.

Ice was cut in blocks from the lake during the winter and dragged up to the Ice house. A drain at the bottom allowed water from the melted ice to escape. The structure was built mainly underground where the temperature is more consistently cool.

The Ice House at Compton Verney was originally thatched, but after 1817 there are no further records of re-thatching or repair and the Ice House was either abandoned or possibly covered in earth and grass – an approach seen with other Ice Houses – as this was how it was found when the present owners took over Compton Verney in the 1990s. Clearance of the Ice House at Compton Verney started in 2008. The Ice House has now been fully restored.[14][15]

19th century

When The 14th Baron Willoughby de Broke died in 1816, the house was inherited by The 15th Baron Willoughby de Broke, and on his death by his younger brother, who became The 16th Baron Willoughby de Broke (1773–1852), an eccentric character who became increasingly reclusive. He made minor alterations to the building, such as architect Henry Hakewill’s transformation of the Saloon into a Dining room in 1824. There was also some work in the grounds, including the extension of the lower lake in around 1815 by the engineer William Whitmore, and the erection of a White Cornish granite obelisk over the old family vault near the lake in about 1848. This structure is said to have been based on the Lateran Obelisk in Italy.[16] The 17th Baron Willoughby de Broke (1809–1862), whose name was originally Robert John Bernard, did very little to the house as he was more interested in hunting. The 18th Baron invited architect John Gibson to work on the site. He made changes to the Hall, which included the addition of a splendid hunting frieze, the decorated ceiling and a new external door. He also added lodges to the main gates.

The 18th Baron also made significant changes to the landscape, the most dramatic being the addition of a long, majestic crescent of Wellingtonia (also known as Giant Sequoias or Sierra Redwoods) between the Upper bridge and the south-eastern gate.

Since then, the history of the estate over the last 150 years has been a chequered one. Compton Verney suffered in the agricultural depression of the 1870s and 1880s, in common with other landed estates across the country, as they were dependent on agricultural rent for income. The house was let out from 1887 to 1902 due to this.[4][17]

20th century

The last Verney to live in the mansion was Richard Greville Verney (1869–1923), 19th Baron Willoughby de Broke, whose nostalgic memoir, The Passing Years, offers a sentimental description of life in the house before he was obliged to sell it in 1921. He died two years later, in 1923.

During the next 70 years the estate changed hands a number of times. The new owner in 1921 was Joseph Watson (1873 – 13 March 1922), of Linton Spring near Wetherby in Yorkshire, a soap manufacturer at Leeds.[18] Having merged the core part of his business into what became Unilever and sold his holding, he retired relatively young in his 40s intending to devote the rest of his life to horse-racing, fox-hunting and the life of a country gentleman, whilst also redirecting his business acumen into pioneering industrial agriculture on other estates he had acquired with his proceeds, namely at nearby Offchurch, at Selby in Yorkshire and at Orford in Suffolk. He purchased the famous racehorse training estate of Manton in Wiltshire, and in 1921 had already produced horses which won The Oaks, the Grand Prix de Paris (the world's highest prize-money) and a 3rd place in The Derby, for which the racing press called him "Mr Lucky Watson".

In 1922, he was made The 1st Baron Manton, of Compton Verney in the County of Warwick,[18] for his wartime services in manufacturing munitions at Barnbow near Leeds; however, just a few months later, he died from a heart attack following a fall whilst out hunting with the Warwickshire Foxhounds near his new seat.[19] Lord Manton was buried at his nearby manor of Offchurch, where he was living pending the refurbishment of Compton Verney. His funeral procession departed Compton Verney followed on foot by over one hundred estate workers to the church at Offchurch.[20] His eldest son Miles, 2nd Baron Manton (1899–1968), sold the house in 1929 (having, with much public disapproval, sold the mediaeval stained glass in the Verney Chapel)[21] to the Manchester cotton manufacturer Samuel Lamb, who moved out during the Second World War when Compton Verney was requisitioned by the army. During the war the grounds were used as an experimental station for smoke-screen camouflage, as an outstation of the Camouflage School established at Stratford-upon-Avon.[22]

After the army left in 1945, the house was never lived in again. In 1958, it was acquired by Harry Ellard, a local property and nightclub owner, who occasionally authorised film companies to shoot there. One such film was Peter Hall's 1968 film of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, which was shot both inside the house and in the grounds.[23] Licking Hitler, a fictional account of a wartime propaganda station in a requisitioned house, was filmed at the property in 1977.[24]

By the 1980s, Compton Verney had become semi-derelict.[17][25]

Peter Moores Foundation

In 1993 the visual arts charity Peter Moores Foundation bought the property and restored the original building. The architectural practice Stanton Williams was commissioned to repurpose it as an art museum, designing a new wing and providing exhibition spaces and visitor facilities.[26] This now houses the British Folk Art Collection, the largest collection of British naive art in the UK.[27][28]

See also

References

- ^ "COMPTON VERNEY HOUSE TRUST, registered charity no. 1032478". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

- ^ Compton Verney: Collections

- ^ The Antiquities of Warwickshire 1656 and 1730 (Second ed.). Newton Regis. 1730.

- ^ a b c d Bearman, Robert, ed. (2000). Compton Verney : a history of the house and its owners. Stratford-upon-Avon: Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. ISBN 978-0904201031.

- ^ Jonathan Parkhouse. Shakespeare’s County’: Warwickshire c1550-1750. www.birmingham.ac.uk: Warwickshire County Council.

- ^ "Verney, family, Barons Willoughby de Broke". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Patrick Baty. "Compton Verney, Warwickshire". patrickbaty.co.uk/. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "The stable block and formal gardens". Compton Verney House. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "Robert Adam Neo-Classical Architect and Designer". www.vam.ac.uk. UK: Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Compton Verney Collection". www.pmf.org.uk. Peter Moores Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "British History Online: Compton Verney". www.british-history.ac.uk/.

- ^ "Capability Brown and the Landscape of Middle England" (PDF). www.comtponverney.org.uk. Compton Verney House Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Managing a Capability Brown Landscape". www.my-garden-school.com/. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Compton Verney Ice House Restoration". englishbuildings.blogspot.co.uk. Philip Wilkinson. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Compton Verney House and Gallery". www.johncgoom.co.uk. J C Groom Architects and Historic Building Consultants. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Nicholson, Jean et al: The Obelisks of Warwickshire, page 28. Brewin Books, 2013

- ^ a b "19th & 20th Century Compton Verney". www.comptonverney.org.uk. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ a b Longstreth Thompson, Francis (1963). English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century (2007 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 333.

- ^ "Death of Lord Manton". The Times. London. 14 March 1922. p. 12.

- ^ "Funeral Lord Manton". The Times. 18 March 1922. p. 13.

- ^ "Demand for old stained glass". The Times. 3 April 1936. p. 9.

- ^ "Military Training at Compton Verney". memoriesofcomptonverney.org.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Hall, Peter; Mullin, Michael (December 1975). "Peter Hall's "Midsummer Night's Dream" on Film". Educational Theatre Journal. 27 (4): 529. doi:10.2307/3206388.

- ^ Hare, David (1984). The history plays. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 11–15. ISBN 0-571-13132-8.

- ^ "Memories of Compton Verney". memoriesofcomptonverney.org.uk. Compton Verney. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Compton Verney Art Gallery, Warwickshire". stantonwilliams.com. Stanton Williams. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Saved! by the Peter Moores Foundation". Compton Verney House. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "British Folk Art Collection". Compton Verney House. Retrieved 1 August 2022.