Complementizer

In linguistics (especially generative grammar), a complementizer or complementiser (glossing abbreviation: comp) is a functional category (part of speech) that includes those words that can be used to turn a clause into the subject or object of a sentence. For example, the word that may be called a complementizer in English sentences like Mary believes that it is raining. The concept of complementizers is specific to certain modern grammatical theories. In traditional grammar, such words are normally considered conjunctions. The standard abbreviation for complementizer is C.

Category of C

C as head of CP

The complementizer is often held to be the syntactic head of a full clause, which is therefore often represented by the abbreviation CP (for complementizer phrase). Evidence of the complementizer functioning as the head of its clause includes that it is commonly the last element in a clause in head-final languages like Korean or Japanese in which other heads follow their complements, but it appears at the start of a clause in head-initial languages such as English in which heads normally precede their complements.[1]

The trees below illustrate the phrase "Taro said that he married Hanako" in Japanese and English; syntactic heads are marked in red and demonstrate that C falls in head-final position in Japanese, and in head-initial position in English.

太郎は

Taro-wa

Taro-TOP

「花子と

Hanako-to

Hanako-and

結婚した」と

kekkonsi-ta-to

marry-PST-COMP

言った

it-ta.

say-PST

'Taro said that he married Hanako.' [2]

Sources of C

It is common for the complementizers of a language to develop historically from other syntactic categories, a process known as grammaticalization.

C can develop from a determiner

Across world languages, pronouns and determiners are especially commonly used as complementizers (e.g., English that).

- I read in the paper that it's going to be cold today.

C can develop from an interrogative word

Another frequent source of complementizers is the class of interrogative words. It is especially common for a form that otherwise means what to be borrowed as a complementizer, but other interrogative words are often used as well, as in the following colloquial English example in which unstressed how is roughly equivalent to that.

- I read in the paper how it's going to be cold today.

C can develop from a preposition

With non-finite clauses, English for in sentences like I would prefer for there to be a table in the corner shows a preposition that has arguably developed into a complementizer. (The sequence for there in this sentence is not a prepositional phrase under this analysis.)

C can develop from a verb

In many languages of West Africa and South Asia, the form of the complementizer can be related to the verb say. In those languages, the complementizer is also called the quotative, which performs many extended functions.

Empty complementizers

Some analyses allow for the possibility of invisible or "empty" complementizers. That is considered to be present if there is no word even though the rules of grammar expect one. The complementizer (for example, "that") is usually said to be understood. An English-speaker knows that it is there and so it does not need to be said. Its existence in English has been proposed based on the following type of alternation:

- He hopes you go ahead with the speech

- He hopes that you go ahead with the speech

Because that can be inserted between the verb and the embedded clause without changing the meaning, the original sentence without a visible complementizer would be reanalyzed as

- He hopes ∅C you go ahead with the speech

Where the symbol ∅C represents the empty (or "null") complementizer, that suggests another interpretation of the earlier "how" sentence:

- I read in the paper <how> ∅C [it's going to be cold today]

where "how" serves as a specifier to the empty complementizer, which allows for a consistent analysis of another troublesome alternation:

- The man <whom> ∅C [I saw yesterday] ate my lunch!

- The man <OP> ∅C [I saw yesterday] ate my lunch!

- The man <OP> that [I saw yesterday] ate my lunch!

where "OP" represents an invisible interrogative known as an operator.

In a more general sense, the proposed empty complementizer parallels the suggestion of near-universal empty determiners.

Various analyses have been proposed to explain when the empty complementizer ∅ can substitute for a phonologically overt complementizer. One explanation is that complementizers are eligible for omission when they are epistemically neutral or redundant. For example, in many environments, English's epistemically neutral that and Danish's at can be omitted. In addition, if a complementizer expresses a semantic meaning that is also expressed by another marker in the phrase, the complementizer that carries the redundant meaning may be omitted. Consider the complementizer be in Mbula, which expresses uncertainty, in the following example:

Here, the marker ko also expresses epistemic uncertainty, so be can be replaced by the phonologically null complementizer without affecting meaning or grammaticality.[4]

Complementizers are present in a wide range of environments. In some, C is obligatorily overt and cannot be replaced by the empty complementizer. For example, in English, CPs selected for by manner-of-speaking verbs (whisper, mutter, groan, etc) resist C-drop:[5]

- Barney whispered *(that) Wilma was dating Fred.

- Barney said (that) Wilma was dating Fred.

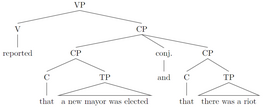

In other environments, the complementizer can be omitted without loss of grammaticality but may result in semantic ambiguity. For example, consider the English sentence "The newspaper reported that a new mayor was elected and (that) there was a riot." Listeners can infer a causal relationship between the two events reported by the newspaper. A new mayor was elected, and as a result, there was a riot. Alternatively, the events may be interpreted as independent of each other. The non-causal interpretation is more likely when the second complementizer that is present, but the causal interpretation is more likely when an empty complementizer is present.[6]

The ambiguity here arises because the sentence in which the second complementizer is empty may also be interpreted as simply having no second complementizer. In the former case, the sentence involves co-ordination of CPs, which lends itself more easily to a non-causal interpretation, but the latter case involves co-ordination of TPs, which is the necessary structure for a causal interpretation.[7] Partial syntax trees for the possible structures are given below.

Selectional restrictions imposed by C

As a syntactic head, C always selects for a complement tense phrase (TP) whose syntax and semantics are dictated by the choice of C. The choice of C can determine whether the associated TP is finite or non-finite, whether it carries the semantic meaning of certainty or uncertainty, whether it expresses a question or an assertion, etc.

Propositions vs. indirect questions

The following complementizers are available in English: that, for, if, whether, ∅.[8]

If and whether form CPs that express indirect questions:[8]

- John wonders whether / if it is raining outside.

In contrast, the complementizers for, that, as well as the phonologically null complementizer ∅, introduce "declarative or non-interrogative" CPs.[8]

- John thinks ∅ it is raining outside.

- John thinks that it is raining outside.

- John prefers for it to be raining.

Finite vs. non-finite TPs

Tense phrases in English can be divided into finite (tensed) clauses or non-finite (tenseless) clauses. The former includes an indication of the relative time when its content occurs; the latter has no overt indication of time. Compare John will leave (John's leaving will take place in the future) with John wants to leave (we are unsure when John is leaving).[8]

Certain complementizers strictly select for finite clauses (denoted [+finite]) while others select for non-finite clauses (denoted [-finite]).

Complementizers if, that require [+tense] TP:

- Mary wishes that she will win the game. (future)

- Mary believes if she wins the game, she can date John. (present)

Complementizer for requires a [-tense] TP:

- Mary hopes for Kate to win the game. (infinitive)

Complementizer whether allows either [+tense] or [-tense] TP:

- John wonders whether Mary will win the game. (future)

- Mary wonders whether to win the game or not. (infinitive)

| Category | Sub-category | English examples | Number (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complementizer (C) | finite C | {∅, that} | n = 5 |

| non-finite C | {∅, for} | ||

| interrogative C | {∅, if, whether} |

Epistemic selection

Complementizers frequently carry epistemic meaning about the speaker's degree of certainty, such as whether they are doubtful, or the speaker's source of information, such as whether they are making an inference or have direct evidence. Contrast the meaning of "if" and "that" in English:

- John doesn't know if Mary is there.

- John doesn't know that Mary is there.

"If" signals that the associated tense phrase must carry the epistemic meaning of uncertainty. In contrast, "that" is epistemically neutral.[10] The contrast is not uncommon cross-linguistically. In languages with only two complementizers, one is frequently neutral, and the other carries the meaning of uncertainty. One such language is Lango (a Nilotic language spoken in Uganda):[10]

ɲákô

girl

áokobbɪ̀

3SG.say.BEN.PFV

dákô

woman

[nî

COMP

dyεl

goat

ocamo].

3SG.eat.PFV

'The girl told the woman that the goat ate it.' [11]

dákô

woman

párô

3SG.consider.HAB

apárâ

consider.GER

[ká

COMP

ɲákô

girl

orego

3SG.grind.PFV

kál].

millet

'The woman doubts whether the girl ground the millet.' [12]

Additional languages with the neutrality/uncertainty complementizer contrast include several European languages:[13]

| Language | Neutral complementizer | Uncertain complementizer |

|---|---|---|

| Faroese | at 'that' | um 'if' |

| Neo-Aramaic | qed 'that' | in 'if' |

| Bulgarian | ce 'that' | dali 'if, whether' |

| Estonian | et 'that' | kas 'if, whether' |

| Irish | go 'that' | an 'if, whether' |

In other languages, complementizers are richer in epistemic meaning. For example, in Mbula, an Austronesian language of Papua New Guinea, the following complementizers are available:[15]

| Complementizer | Epistemic meaning |

|---|---|

| kokena be / ∅ | 'lest' (="I don't want this to happen") |

| (ta)kembei | 'like' (="I think like this.") |

| ∅ | 'asserted factuality' (="I say this is something that has happened or is happening.") |

| ta(u) / ∅ | 'presupposed factuality' (="I know that this is something which has happened, and I think that you know about it too.") |

| tabe | 'presupposed non-factuality' (="I know that this is something which has happened and that you know about it.") |

| ki | 'habitual event' (="This is the kind of thing that is always happening.") |

More generally, complementizers have been found to express the following values cross-linguistically: certainty, (general) uncertainty, probability, negative probability/falsehood, apprehension, and reportativity.[16]

Complementizers in Itzaj Maya also demonstrate epistemic meaning. For instance, English that and Itzaj Maya kej are used not only to identify complements but also to introduce relative clauses:[17]

Ma’

NEG

t-inw-ojel-t-aj

?-1SG.A-know-TR-ITS

[ke

COMP

t-u-b ’et-aj].

COMPL-3.A-do-CTS

‘I didn’t know that he did it.’ [18]

Ma’

NEG

inw-ojel

1SG.A-know

[wa

COMP

t-u-b ’et-aj].

COMPL-3.A-do-CTS

‘I don’t know if he did it.’ [18]

(1a) introduces a subordinate clause and (1b) introduces a conditional clause, similar to English. The former subtype that can be defined in terms of information source and includes meanings glossed as direct evidence, indirect evidence, hearsay, inferential. The latter subtype if can be defined in terms of degree of certainty and includes meanings glossed as certainty, probability, epistemic possibility, doubt. Thus, epistemic meaning as a whole can be defined in terms of the notion of justificatory support.[10]

Complementizer stacking

Itzaj Maya can even combine the neutral complementizer, ke, with the non-neutral, waj, as is illustrated in examples (2a) in which the neutral complementizer ke occurs alone and (2b) in which it is optionally inserted in front of the uncertainty complementizer waj:[13][19]

Uy-ojel

3-know

[ke

COMP

la’ayti’

3.PRO

u-si’pil

3-crime

t-u-jaj-il].

to-3-true-ABST

‘He knows that it is his crime truly.’ [20]

Ka’

when

t-inw-a’al-aj

COMPL-1SG-say-TR

ti’ij

3.INDIR.OBJ

[(ke)

COMP

wa

COMP

patal-uy-an-t-ik-en].

ABIL-3-help-TR-INCH-1SG

‘And I asked her if she could help me.’ [20]

In (1a,b) and (2a), each complementizer can be licensed once within the clause, but in (2b), the significant difference of Itzaj Maya from English is observed. English can license multiple C as long as the clause is completed with the embedded V or D. For example, I saw that fox that ran towards the garden that Tommy took care of. In such cases, C can appear as the complement of V or D many times. However, CP-recursion in two tiers or CP appearing as an immediate complement of maximal projection CP cannot be allowed in English. That action of Complementizer Stacking is realised as ungrammatical.

In Scandinavian languages, however, the phenomenon of complementizer stacking occurs. For example, researchers observed the two basic types of CP-recursion that occur independently in Danish: a CP with V2 (i.e. a CP headed by a lexical predicate in its head position) will be referred as CP ("big CP"), and a CP without V2 (i.e. CP headed by a non-lexical element) will be referred to as cP ("little cP").[22]

- [cP c° [– LEXICAL]] ("little cP")

- [cP C° [+ LEXICAL]] ("big CP")[23]

The case of little/big CPs are comparable to the "VP shell" structure in English, which introduces a small v in the higher position in the tree and big V in the lower position in the tree.

In the examples, Danish also allows complementizer stacking in constructions involving subject extraction from complement and relative clauses in colloquial speech:

Vi

We

kender

know

de

the

lingvister

linguists

…

[cP

OP1

[c°

som]

that.REL

[cP

[c°

at]

that.COMP

[cP

[c°

der]

that.REL

[IP

__1

vil

will

læse

read

den

this

her

here

bog]]]].

book

Peter

påstod

[cP

[c°

at]

[CP

det

her1

[C°

kunne]

han

gøre

__1

meget

bedre]]

Peter claimed that this here could he do much better [22]

Complementizers are indeed stacked together in the beginning of the clause and act as a complement of DP. CP-recusion structure on the right is applied for each of the clause, which points to evidence of complementizer stacking in Danish. In addition, the combination of som at der in (3a) is possible in only one specific order, which led the researchers to believe that som may not require an empty operator in its Spec-CP position.[22]

In various languages

Assyrian Neo-Aramaic

In Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, a modern Aramaic language, kat (or qat, depending on the dialect) is used as a complementizer and is related to the relativizer. It is less common in casual speech but more so in formal conversation.

Hebrew

In Hebrew (both Modern and Ancient), two complementizers co-exist:[24] שֶ [ʃe], which is related to the relativizer asher ( < Akkadian ashru 'place') and/or to the pronominal Proto-Semitic dhu ('this'); and כִּי [ki], which is also used as a conjunction meaning 'because, when'. In modern usage, the latter is reserved for more formal writing.

American Sign Language

Some manual complementizers exist in American Sign Language, but they are usually expressed non-manually by facial expressions. Conditional clauses, for example, are indicated by raised eyebrows. A manual complementizer, if used, is also accompanied by a facial expression.[25] The non-manual marking of complementizers is a common phenomenon found in many sign languages, and it has even been suggested by Fabian Bross that C-categories are universally marked with the face in sign languages.[26]

See also

References

- ^ Sells 1995.

- ^ Ishihara 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Bugenhagen 1991, p. 270.

- ^ Boye, van Lier & Theilgaard Brink 2015, p. 13.

- ^ de Cuba 2018, p. 32–1–13.

- ^ Rohde, Tyler & Carlson 2017, p. 53.

- ^ Bjorkman 2013, p. 391–408.

- ^ a b c d Sportiche, Koopman & Stabler 2014.

- ^ Sportiche, Koopman & Stabler 2014, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Boye, van Lier & Theilgaard Brink 2015, p. 1–17.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 220.

- ^ Noonan 1992, p. 220, 227.

- ^ a b Nordström & Boye 2016, p. 131–174.

- ^ Nordström & Boye 2016, p. 8.

- ^ a b Bugenhagen 1991, p. 226.

- ^ Boye, van Lier & Theilgaard Brink 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Hofling & Tesucún 2000, p. 496, 495.

- ^ a b Boye, van Lier & Theilgaard Brink 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Hofling & Tesucún 2000, p. 495, 506.

- ^ a b c Boye, van Lier & Theilgaard Brink 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Nyvad, Christensen & Vikner 2017, p. 451.

- ^ a b c Nyvad, Christensen & Vikner 2017, p. 463-464.

- ^ Nyvad, Christensen & Vikner 2017, p. 453.

- ^ Zuckermann 2006, p. 79–81.

- ^ Liddell 1980.

- ^ Bross 2020.

- Nyvad, Anne Mette; Christensen, Ken Ramshøj; Vikner, Sten (2017-01-01). "CP-recursion in Danish: A cP/CP-analysis". The Linguistic Review. 34 (3). doi:10.1515/tlr-2017-0008. ISSN 0167-6318. S2CID 171704958.

- Boye, Kasper; van Lier, Eva; Theilgaard Brink, Eva (2015-09-01). "Epistemic complementizers: a cross-linguistic survey". Language Sciences. 51: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2015.04.001. ISSN 0388-0001 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Nordström, Jackie; Boye, Kasper (2016-07-11). "Complementizer semantics in the Germanic languages". Complementizer Semantics in European Languages. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110416619-007. ISBN 9783110416619.

- Noonan, Michael (1992). A grammar of Lango. Mouton Grammar Library. Vol. 7. Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110850512. ISBN 9783110129922.

- Hofling, Charles Andrew; Tesucún, Félix Fernando (2000). Itzaj Maya grammar. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-218-0. OCLC 812924896.

- Bjorkman, Bronwyn M. (2013). "A syntactic answer to a pragmatic puzzle: The case of asymmetric and". In Folli, Raffaella; Sevdali, Christina; Truswell, Robert (eds.). Syntax and its Limits. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199683239.003.0019. ISBN 9780199683239.

- Bugenhagen, Robert D. (1991). A grammar of Mangap-Mbula: an Austronesian language of Papua New Guinea (Ph.D. thesis). doi:10.25911/5d723a51866ce.

- Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda Judith; Stabler, Edward P (2014). An introduction to syntactic analysis and theory. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 9781118470480.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2006). "Complement Clause Types in Israeli". In R. M. W. Dixon; Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.). Complementation: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rohde, Hannah; Tyler, Joseph; Carlson, Katy (2017). "Form and function: Optional complementizers reduce causal inferences". Glossa (London). 2 (1). doi:10.5334/gjgl.134. ISSN 2397-1835. PMC 5552188. PMID 28804781.

- de Cuba, Carlos (2018-03-03). "Manner-of-speaking that-complements as close apposition structures". Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America. 3 (1). doi:10.3765/plsa.v3i1.4320. ISSN 2473-8689.

- Ishihara, Yuki (September 2021). "Root Complementizer tte in Japanese" (PDF). Japanese/Korean Linguistics. 28.

- Sells, Peter (1995). "Korean and Japanese Morphology from a Lexical Perspective". Linguistic Inquiry. 26 (2): 277–325. ISSN 0024-3892. JSTOR 4178898.

- Liddell, Scott K. (1980). American Sign Language Syntax. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783112418260.

- Bross, Fabian (2020). The clausal syntax of German Sign Language: A cartographic approach (PDF). Berlin: Language Science Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on Nov 25, 2022.