Coccyx

| Coccyx | |

|---|---|

The coccyx | |

The coccyx is the final bone in the vertebral column that surrounds the spinal cord. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒksɪks/ KOK-siks |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os coccygis |

| MeSH | D003050 |

| TA98 | A02.2.06.001 |

| TA2 | 1092 |

| FMA | 20229 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

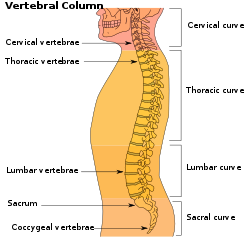

The coccyx (pl.: coccyges or coccyxes), commonly referred to as the tailbone, is the final segment of the vertebral column in all apes,[1] and analogous structures in certain other mammals such as horses. In tailless primates (e.g. humans and other great apes) since Nacholapithecus (a Miocene hominoid),[2][3] the coccyx is the remnant of a vestigial tail. In animals with bony tails, it is known as tailhead or dock, in bird anatomy as tailfan. It comprises three to five separate or fused coccygeal vertebrae below the sacrum, attached to the sacrum by a fibrocartilaginous joint, the sacrococcygeal symphysis, which permits limited movement between the sacrum and the coccyx.

Structure

The coccyx is formed of three, four or five rudimentary vertebrae. It articulates superiorly with the sacrum. In each of the first three segments may be traced a rudimentary body and articular and transverse processes; the last piece (sometimes the third) is a mere nodule of bone. The transverse processes are most prominent and noticeable on the first coccygeal segment. All the segments lack pedicles, laminae and spinous processes. The first segment is the largest; it resembles the lowest sacral vertebra, and often exists as a separate piece; the remaining ones diminish in size rostrally.

Most anatomy books incorrectly state that the coccyx is normally fused in adults. It has been shown that the coccyx may, in some people, consist of up to five separate bony segments, the most common configuration being two or three segments.[4]

Surfaces

The anterior surface is slightly concave and marked with three transverse grooves which indicate the junctions of the different segments. It gives attachment to the anterior sacrococcygeal ligament and the levatores ani and supports part of the rectum. The posterior surface is convex, marked by transverse grooves similar to those on the anterior surface, and presents on either side a linear row of tubercles – the undeveloped articular processes of the coccygeal vertebrae. Of these, the superior pair are the largest, and are called the coccygeal cornua they project caudally, and articulate with the cornua of the sacrum, and on either side complete the foramen for the transmission of the posterior division of the fifth sacral nerve.

Borders

The lateral borders are thin and exhibit a series of small bony protrusions, which represent the transverse processes of the coccygeal vertebrae. Of these, the first is the largest; it is flattened anteriorly, and often extends to join the lower part of the thin lateral edge of the sacrum, thus completing the foramen for the transmission of the anterior division of the fifth sacral nerve; the others diminish in size from caudally, and are often lacking. The borders of the coccyx are narrow, and give attachment on either side to the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, to the coccygeus and levator ani in front of the ligaments, and to the gluteus maximus behind them.

Apex

The apex is rounded, and has attached to it the tendon of the external anal sphincter; it may be divided in two.

Coccygeal fossa

The coccygeal fossa is a shallow depression on the posterior surface between the sacrum and the perineum, located in the intergluteal cleft that runs from just below the sacrum to the perineum.[clarification needed][5] It is not consistently present in all humans. The coccygeal fossa marks the deepest part of the pelvic floor, next to the coccyx. The levator ani has its origin here.[6]

Extensor coccygis

The extensor coccygis is a slender muscle fascicle, which is not always present. It extends over the caudal portion of the posterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx. It arises by tendinous fibers from the last segment of the sacrum, or first piece of the coccyx, and passes downward to be inserted into the lower part of the coccyx. It is an evolutionary relic of the extensor muscle of the caudal vertebrae of other animals, enabling limited coccygeal motion.

Sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal joints

The joints are variable and may be: (1) synovial joints; (2) thin discs of fibrocartilage; (3) intermediate between these two; (4) ossified.[7][8]

Attachments

The anterior side of the coccyx has attachments to the levator ani muscle, coccygeus, iliococcygeus, and pubococcygeus, anococcygeal raphe. Attached to the posterior side is the gluteus maximus, which extends the thigh at the hip joint.[9] The ligaments attached to the coccyx include the anterior and posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments which are the continuations of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments that extend along the entire spine.[9] The lateral sacrococcygeal ligaments complete the foramina for the last sacral nerve.[10] Some fibers of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments (arising from the spine of the ischium and the ischial tuberosity respectively) also attach to the coccyx.[9] An extension of the pia mater, the filum terminale, extends from the apex of the conus, and inserts on the coccyx.

Function

The coccyx is not entirely useless in humans,[11] because it has attachments to various muscles, tendons and ligaments. However, these muscles, tendons and ligaments are also attached at many other points, to stronger structures than the coccyx. It is doubtful that the coccyx attachments are important to the well-being of humans, given the large number of coccygectomy procedures performed annually to treat coccydynia. Reviews of studies covering more than 700 coccygectomies found the operation was successful in relieving pain in 84% of cases.[12][13] 12% of the time, the only major complication faced was infection due to the proximity to the anus. One notable complication of coccygectomy is an increased risk of perineal hernia.

Clinical significance

Injuring the coccyx can give rise to a painful condition called coccydynia and one or more of the bones or the connections thereof may be broken, fractured tailbone.[14][15] A number of tumors are known to involve the coccyx; of these, the most common is sacrococcygeal teratoma. Both coccydynia and coccygeal tumors may require surgical removal of the coccyx (coccygectomy). One very rare complication of coccygectomy is a type of perineal hernia known as a coccygeal hernia.[16]

Etymology

The term coccyx is derived from the ancient Greek word κόκκυξ[17][18] kokkyx "cuckoo";[19] the latter is attested in the writings of the Greek physician Herophilus to denote the end of the vertebral column.[20] This Greek name for the cuckoo was applied as the last three or four bones of the coccyx resemble the beak of this bird,[17][20][21][22] when viewed from the side.[9][23]

This established etymological explanation can also be found in the writings of the 16th century anatomist Andreas Vesalius who wrote: os cuculi, a similitudine rostri cuculi avis[20] (the cuckoo bone shows a likeness to the beak of the cuckoo bird). Vesalius used the Latin expression os cuculi, with os, bone[24] and cuculus, the Latin name for the cuckoo.[24] The 16th/17th century French anatomist Jean Riolan the Younger gives a rather hilarious etymological explanation, as he writes: quia crepitus, qui per sedimentum exeunt, ad is os allisi, cuculi vocis similitudinem effingunt[20] (because the sound of the farts that leave the anus and dash against this bone, shows a likeness to the call of the cuckoo). Riolan's explanation is not considered credible.[20][21]

Besides os cuculi, os caudae,[20][25] with caudae, of the tail[24] is attested. This Latin expression might be the source of the English, French language, German and Dutch terms tailbone, l'os de la queue,[25] Schwanzbein[21][25] and staartbeen.[26] In the current official anatomic Latin nomenclature, Terminologia Anatomica,[27] coccyx and os coccygis is used.

Additional images

- The coccyx sits below the sacrum and behind the pelvic cavity.

See also

References

- ^ Weisberger, Mindy (March 23, 2024). "Why don't humans have tails? Scientists find answers in an unlikely place". CNN. Archived from the original on March 24, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ Nakatsukasa 2004, Acquisition of bipedalism (See Fig. 5 entitled First coccygeal/caudal vertebra in short-tailed or tailless primates..)

- ^ Note: Nacholapithecus and Nakaliphitecus nakayamai are two different species of Miocene hominoids (specimens from Nakali and Nachola respectively). See for example "Comparisons with Other Hominoids" in (Kunimatsu, Nakatsukasa et al. Dec 2007)

- ^ Tetiker H, Koşar MI, Çullu N, Canbek U, Otağ I, Taştemur Y (2017). "MRI-based detailed evaluation of the anatomy of the human coccyx among Turkish adults". Niger J Clin Pract. 20 (2): 136–142. doi:10.4103/1119-3077.198313. PMID 28091426.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cosmo, L (2017). "Filling the Gap: on the New Micro-toponomic Phenomena and Partial Topologies". Health Research. 1 (1): 39–49. doi:10.31058/j.hr.2017.11004.

- ^ Lierse, Werner (2012-12-06). Applied anatomy of the pelvis. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 978-3-642-71368-2.

- ^ Maigne JY; Molinie V; Fautrel B (1992). "Anatomie des disques coccygiens". Revue de Médecine Orthopedique. 28: 34–35.

- ^ Saluja PG (1988). "The incidence of ossification of the sacrococcygeal joint". Journal of Anatomy. 156: 11–15. PMC 1261909. PMID 3138225.

- ^ a b c d Foye, Patrick M; Buttaci, Charles J (June 3, 2008). "Coccyx Pain". eMedicine.

- ^ Morris, Craig E. (2005). Low Back Syndromes: Integrated Clinical Management. McGraw-Hill. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-07-137472-9.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2003). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 268.

- ^ Coccygektomi kan være en behandlingsmulighed ved kronisk coccygodyni (Coccygectomy may be a treatment option for chronic coccydynia) Ugeskr Læger 2011 Feb 14; 173(7): 495-500. In Danish. Aarby, Nanett Skjellerup (1), Trollegaard, Anton Mitchell (2) and Hellberg, Steen (2) https://www.coccyx.org/medabs/aarby.htm

- ^ Heum Dai Kwon et al., Coccygodynia and Coccygectomy. Korean Journal of Spine, 9, 4 (2012), 326-333.

- ^ Maigne, J-Y; Doursounian, L; Chatellier, G (2000). "Causes and Mechanisms of Common Coccydynia. Spine". Spine. 25 (23). coccyx.org: 3072–3079. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012010-00015. PMID 11145819. S2CID 25790826.

- ^ Foye P, Buttaci C, Stitik T, Yonclas P (2006). "Successful injection for coccyx pain". Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 85 (9): 783–784. doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000233174.86070.63. PMID 16924191.

- ^ Miranda EP, Anderson AL, Dosanjh AS, Lee CK (September 2007). "Successful management of recurrent coccygeal hernia with the de-epithelialised rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap". J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 62 (1): 98–101. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.08.002. PMID 17889632.

- ^ a b Klein, E. (1971). A comprehensive etymological dictionary of the English language. Dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustration the history of civilization and culture. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "coccyx". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ κόκκυξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ a b c d e f Hyrtl, J. (1880). Onomatologia Anatomica. Geschichte und Kritik der anatomischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Wien: Wilhelm Braumüller. K.K. Hof- und Universitätsbuchhändler.

- ^ a b c Kraus, L.A. (1844). Kritisch-etymologisches medicinisches Lexikon (Dritte Auflage). Göttingen: Verlag der Deuerlich- und Dieterichschen Buchhandlung.

- ^ Panourias, I.G.; Stranjalis, G.; Stavrinou, L.C.; Sakas, D.E. (2011). "The Hellenic and Hippocratic origins of the spinal terminology". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 20 (3): 177–187. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2010.510180. PMID 21736439. S2CID 22256856.

- ^ Sugar, Oscar (February 1995). "Historical Perspective Coccyx: The Bone Named for a Bird". Spine. 20 (3): 379–383. doi:10.1097/00007632-199502000-00024. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 7732478.

- ^ a b c os, cuculus, cauda. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ a b c Schreger, C.H.Th.(1805). Synonymia anatomica. Synonymik der anatomischen Nomenclatur. Fürth: im Bureau für Literatur.

- ^ Everdingen, J.J.E. van, Eerenbeemt, A.M.M. van den (2012). Pinkhof Geneeskundig woordenboek (12de druk). Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.

- ^ Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) (1998). Terminologia Anatomica. Stuttgart: Thieme

Further reading

- Kunimatsu, Yutaka; Nakatsukasa, Masato; et al. (December 2007). "A new Late Miocene great ape from Kenya and its implications for the origins of African great apes and humans". PNAS. 104 (49): 19220–5. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419220K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706190104. PMC 2148271. PMID 18024593.

- Nakatsukasa, Masato (May 2004). "Acquisition of bipedalism: the Miocene hominoid record and modern analogues for bipedal protohominids". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (5): 385–402. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00290.x. PMC 1571308. PMID 15198702.

External links

- Coccydynia (coccyx pain, tailbone pain) at eMedicine (Peer-reviewed medical chapter, available free online)