John Brown & Company

| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| Industry | Shipbuilding |

| Founded | 1851 |

| Defunct | 1986 |

| Fate | Shipyard amalgamated into Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS), 1968 |

| Successor | Shipyard sold by UCS to Marathon Manufacturing Company, 1972 John Brown Engineering bought by Trafalgar House, 1986 |

| Headquarters | Clydebank, Scotland |

Key people | George Thomson (founder) James Thomson (founder) Charles McLaren, 1st Baron Aberconway (Chairman) Henry McLaren, 2nd Baron Aberconway (Chairman) Charles McLaren, 3rd Baron Aberconway (Chairman) |

| Products | Naval ships Merchant ships Submarines marine engines |

| Parent | John Brown & Company (1899–1968) |

| Subsidiaries | Coventry Ordnance Works |

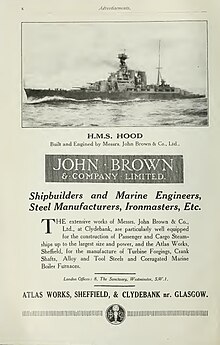

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including RMS Lusitania, RMS Aquitania, HMS Hood, HMS Repulse, RMS Queen Mary, RMS Queen Elizabeth and Queen Elizabeth 2.

At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of the most highly regarded, and internationally famous, shipbuilding companies in the world.[1] However thereafter, along with other UK shipbuilders, John Brown's found it increasingly difficult to compete with the emerging shipyards in Eastern Europe and the far East. In 1968 John Brown's merged with other Clydeside shipyards to form the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders consortium, but that collapsed in 1971.

The company then withdrew from shipbuilding but its engineering arm remained successful in the manufacture of industrial gas turbines. In 1986 it became a wholly owned subsidiary of Trafalgar House, which in 1996 was taken over by Kvaerner. The latter closed the Clydebank engineering works in 2000.

Marathon Manufacturing Company bought the Clydebank shipyard from UCS and used it to build oil rig platforms for the North Sea oil industry. Union Industrielle d'Entreprise (UIE) (part of the French Bouygues group) bought the yard in 1980 and closed it in 2001.

History

Origins

J & G Thomson

Two brothers — James and George Thomson, who had worked for the engineer Robert Napier — founded the engineering and shipbuilding company J&G Thomson. The brothers founded the Clyde Bank Foundry in Anderston in 1847. They opened the Clyde Bank Iron Shipyard at Cessnock, Govan, in 1851 and launched their first ship, Jackal, in 1852. They quickly established a reputation in building prestigious passenger ships, building Jura for Cunard in 1854 and the record breaking Russia in 1867.[2][3][4] Several of the ships they built were bought by the Confederacy for blockade running in the American Civil War, including CSS Robert E. Lee and Fingal which was converted into the ironclad Atlanta.[5]

The brothers separated their business association in 1850 and, after an acrimonious split, George took over the shipbuilding end of the association. James Thomas started a new business. George Thomson died in 1866, followed in 1870 by his brother James.[6] They were succeeded by the sons of the younger brother George, called James Rodger Thomson and George Paul Thomson. Faced with the compulsory purchase of their shipyard by the Clyde Navigation Trust (which wanted the land to construct the new Princes' Dock), they established a new Clyde Bank Iron Shipyard further downriver at the Barns o' Clyde, near the village of Dalmuir, in 1871. This site at the confluence of the tributary River Cart with the River Clyde, at Newshot Island, allowed very large ships to be launched. The brothers soon moved their iron foundry and engineering works to the same site. The connection to the area was so complete that James Rodger Thomson became the first Provost of Clydebank. Despite intermittent financial difficulties, the company developed a reputation based on engineering quality and innovation. The rapid growth of the shipyard and its ancillary works, and the building of housing for the workers, resulted in the formation of a new town which took its name from that of the shipyard which gave birth to it — Clydebank.[2] In 1899 the steelmaker John Brown and Company of Sheffield bought J&G Thomson's Clydebank yard for £923,255 3s 3d.[2]

John Brown & Company

John Brown was born in Sheffield in 1816, the son of a slater. At the age of 14, unwilling to follow his father's plans for him to become a draper, he obtained a position as an apprentice with Earle Horton & Co. The company subsequently entered the steel business and at the age of 21, John Brown with the backing of his father and uncle obtained a bank loan for £500 to enable him to become the company's sales agent. He was so successful, he made enough money to set up his own business, the Atlas Steel Works.[7]

In 1848 Brown developed and patented the conical spring buffer for railway carriages, which was very successful. With a growing reputation and fortune, he moved to a larger site in 1856. He began to make his own iron from iron ore, rather than buying it, and in 1858 adopted the Bessemer process for producing steel. These moves all proved successful and lucrative, and in 1861 he started supplying steel rails to the rapidly expanding railway industry.[7]

His next move was to examine the iron cladding used on French warships. He decided that he could do better, and built a steel rolling mill that, in 1863, was the first to roll 12-inch (300 mm) armour plate for warships. By 1867 his iron cladding was being used on the majority of Royal Navy warships. By then, his workforce had grown to over 4,000 and his company's annual turnover was almost £1 million.[7]

Despite this success, however, Brown was finding it increasingly difficult working with the two partners and shareholders he took into the company in 1859. William Bragge was an engineer, and John Devonshire Ellis came from a family of successful brass founders in Birmingham. As well as contributing a patented design for creating compound iron plate faced with steel, Ellis brought with him his expertise and ability in running a large company. Together, the three partners created John Brown & Company, a limited company. Brown resigned from the company in 1871. In subsequent years he started several new business ventures, all of which failed. Brown died impoverished in 1896, aged 80.[7]

The company Brown had set up with his partners, however, John Brown & Company, continued steadily under the management of Ellis and his two sons (Charles Ellis and William Henry Ellis).

In 1899 the company bought the Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding shipyard from J & G Thomson, and embarked on a new phase in its history, as a shipbuilder.[7] The Director at this stage was John Gibb Dunlop from Thomsons, who took charge of the ship design.[8] A legal case resolved in 1904 by the House of Lords between Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding and Don Jose Ramos Yzquierdo y Castaneda, a minister in the Spanish government, dealt with a situation in which

a party to an agreement has admittedly broken it, and an action was brought for the purpose of enforcing the payment of a sum of money which, by the agreement between the parties, was fixed as that which the defenders were to pay in the event that has happened,[9]

a significant case in the history of legal rulings on penalty clauses and liquidated damages.[10]

John Brown & Company, shipbuilders

In the early 1900s, the company innovated marine engineering technology through the development of the Brown-Curtis turbine, which had been originally developed and patented by the U.S. company International Curtis Marine Turbine Co. These engines' performance impressed the Admiralty, which consequently ordered many of the major Royal Navy warships from John Brown. The first notable order was for the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible, followed by the battlecruisers HMAS Australia, HMS Tiger and the battleship HMS Barham.

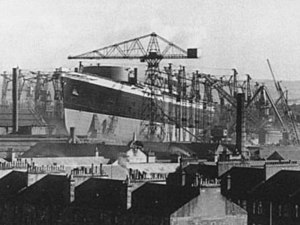

Clydebank also became Cunard Line's preferred shipbuilder, building its flagship liners RMS Lusitania and RMS Aquitania. Prior to construction commencing on Lusitania in 1904 the shipyard was reorganized to accommodate her so that she could be launched diagonally across the widest available part of the river Clyde where it met a tributary (the River Cart), the ordinary width of the river being only 610 feet (190 m) compared to the 786-foot (240 m) long ship. The new slipway took up the space of two existing ones and was built on reinforcing piles driven deeply into the ground to ensure it could take the temporary concentrated weight of the whole ship as it slid into the water. In addition, the company spent £8,000 to dredge the Clyde, £6,500 on a new gas plant, £6,500 on a new electrical plant, £18,000 to extend the dock and £19,000 for a new crane capable of lifting 150 tons, as well as £20,000 on additional machinery and equipment.[11]

In 1905 Brown's established the Coventry Ordnance Works joint venture with Yarrow Shipbuilders and others. In 1909 the company bought a stake in Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval.

World War I

By the early 1900s, the Clydebank works had expanded to cover 80 acres (32 ha) spread along Dumbarton Road, consisting of the East and West yards, which were separated by a fitting out basin, where once launched the hulls are fitted out with the aid of two cranes each capable of lifting 150 tons. The east yard contained five building slipways, each of which could accommodate the building of the largest battleship, with one slip long enough to build a ship of over 900 ft (270 m). The west yard was used to build smaller ships such as destroyers.

Associated with the shipyard was the engine works where the company built turbines and boilers both for its own ships and for other companies.

Apart from a brief period in 1917, the works manager throughout the entire First World War was Thomas Bell. He was knighted in 1918 for his efforts.[12]

Despite being an essential industry the works had difficulty obtaining suitable workers to build all the ships on its order books. In an attempt to reduce the labour shortage it employed women in a number of jobs under a scheme called "dilution" whereby it was agreed with the unions that once the war ended the women would give up their jobs. Throughout the war the company employed on average 10,000 workers at Clydebank works, of which 7,000 were in the shipyard and 3,000 in the engine works.[13] In January 1918, 87 of these were women.

To increase productively, throughout 1914–18 the company continually invested in new facilities and tools. In 1915 it introduced pneumatic riveting which needed only one riveter whereas previously two had been required.

During the war, the company was almost exclusively occupied in building warships. With the exception of the battlecruisers Repulse and Hood, this warship building was concentrated on destroyers. By the end of the war, it had built more destroyers than any other British shipyard and set records for their building with HMS Simoom taking seven months from keel laying to departure, HMS Scythe six months and HMS Scotsman five and a half months.[14] The company estimated that during the entire war period it produced a total of 205,430 tons of shipping and 1,720,000 hp (1,280,000 kW) of machinery.[14]

Between the wars

The end of the First World War and subsequent shortage of naval orders hit British shipbuilding very hard and John Brown only just survived. Three great ships saved the yard: RMS Empress of Britain, and the giant Cunard White Star Liners RMS Queen Mary and RMS Queen Elizabeth. A fictionalised account of the hardships of the industry is portrayed in the 1939 feature film Shipyard Sally.

World War II and after

Although Glasgow's history as a major shipbuilding city made it a prime target for the German Luftwaffe, and despite the Clydebank Blitz, the yard made a valuable contribution in the Second World War, building and repairing many battleships including the notable and highly successful HMS Duke of York. The first few years after the war saw a sudden reduction in warship orders, but it was balanced by a prolonged boom in merchant shipbuilding to replace tonnage lost during the war. The most notable vessels built in this period were the RMS Caronia and the royal yacht HMY Britannia.

By the end of the 1950s, however, shipbuilding in other European nations, and in Korea and Japan, was newly recapitalised and had become highly productive by using new methods such as modular design. Many British yards had continued to use outmoded working practices and largely obsolete equipment, making themselves uncompetitive. At Clydebank the company tendered for a series of break-even contracts, most notably the liner Kungsholm, in the hope of surviving the competition and maintaining production in anticipation of a new high-profile contract from Cunard for a new liner. However, due to rising costs and inflationary pressures, the company suffered major and unsustainable losses, in contrast with the positive portrayal of the industry in the Academy Award-winning film Seawards the Great Ships. By the mid 1960s John Brown & Co's management warned that the shipyard was uneconomic and risked closure. Its last Royal Navy order was for the Fearless-class landing platform dock HMS Intrepid, which was launched in 1964 and underwent trials and commissioning in 1967. The final passenger liner order eventually came from Cunard for Queen Elizabeth 2.

In 1968 the yard merged into Upper Clyde Shipbuilders,[15] but this consortium collapsed in 1971.[16] The last ship to be built at the yard, the Clyde-class bulk grain carrier Alisa, was completed in 1972.[17]

In 1972 UCS's liquidator sold the Clydebank shipyard to Marathon Manufacturing Company. Union Industrielle d'Entreprise (UIE) (part of the French Bouygues group) bought the yard in 1980, using it to build Jack-up and Semi-submersible rigs for North Sea oil fields. UIE closed the yard in 2001.[18]

The commercially successful John Brown Engineering division of the company, which made pipelines and industrial gas turbines and included other subsidiaries such as Markham & Co., continued to trade independently until 1986, when the industrial conglomerate Trafalgar House took it over.[19]

In 1996 Kvaerner bought Trafalgar House.[20] It later was split, with Kvaerner retaining some assets, including the Clydebank-based John Brown Engineering — which became Kvaerner Energy, and Yukos buying John Brown Hydrocarbons and Davy Process Technology, both based in London.[21] In 2000 Kvaerner Energy closed its gas turbine works in Clydebank with the loss of 200 jobs, finally ending the link between John Brown and Clydebank. The site was demolished in 2002. John Brown Hydrocarbons was sold to CB&I in 2003 and renamed CB&I John Brown, and later CB&I UK Limited.[22] A new gas turbine servicing and maintenance company formed by former management of John Brown Engineering, headed by Duncan Wilson and other engineers from the Clydebank site, named John Brown Engineering Gas Turbines Ltd, was re-established in East Kilbride in 2001.[23]

Regeneration of the Clydebank site

A comprehensive regeneration plan for the site is being implemented by West Dunbartonshire Council and Scottish Enterprise. This includes making the Clydebank waterfront more accessible to the public. Restoration of the historic Titan Crane — built by Sir William Arrol & Co. for the shipyard — was completed in 2007.[24] A new campus for Clydebank College was opened in August 2007. Regeneration plans also include improved infrastructure, modern offices, a light industrial estate and new housing, retail and leisure facilities. It was hoped that as part of the plan Queen Elizabeth 2 would be returned to the city and river where she was built, but on 18 June 2007 Cunard Line announced that she would be sold to Dubai as a floating hotel.[25]

Ships built by John Brown & Company

See: List of ships built by John Brown & Company

See also

- John Brown (industrialist) — more about the founder of John Brown & Company.

References

- ^ "John Brown and Company, Clydebank, Scotland UK". Ships and Harbours. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Hood, John (1988). The History of Clydebank. The Parthenon Publishing Group Ltd. pp. 3–5. ISBN 1-85070-147-4.

- ^ "doon-the-watter".html "Sailing Down the Clyde: "Doon the Watter"". Glasgow History. 18 July 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Yards". acumfae Govan. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Joseph McKenna (18 January 2010). British Ships in the Confederate Navy. McFarland. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-7864-5827-1.

- ^ "J. and G. Thomson". Grace's Guide; British Industrial History. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "JOHN BROWN PLC – Company History". International Directory of Company Histories. Vol. 1. St James Press. 1988.

- ^ "John Gibb Dunlop". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. 1 August 2017.

- ^ House of Lords, Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding Co., Limited v. Don Jose Ramos Yzquierdo y Castaneda, 19 November 1904, accessed 8 February 2023

- ^ Referred to as "the Clydebank Case" in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd, 1914 at House of Lords, Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd, paragraph 2

- ^ Fox, page 403

- ^ Johnston,[clarification needed] p. 116

- ^ Johnston,[clarification needed] p. 97

- ^ a b Johnston,[clarification needed] p. 111

- ^ "Government's shipbuilding crisis". BBC News. 1 January 2002.

- ^ "Parliamentary debates". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 4 June 1971.

- ^ Cameron, Stuart. "MV Alisa". Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "John Brown Shipyard". Clyde Waterfront Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Trafalgar to buy John Brown". New York Times. 8 May 1986.

- ^ "Kvaerner buys Trafalgar for £904m deal". The Independent. 5 March 1996.

- ^ "The external investments of Yukos". APS Review. 6 September 2004.

- ^ "CB&I acquires John Brown Hydrocarbons". Businesswire. 2 June 2003. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "John Brown Engineering Gas Turbines Ltd". Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ "History". Titan Clydebank. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ "QE2 Today". Chris' Cunard Page. 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

Bibliography

- Fox, Stephen (2003). The Ocean Railway (hardback). London: Harper Collins. p. 493. ISBN 0-00-257185-4.

- Johnston, Ian; Buxton, Ian (2013). The Battleship Builders – Construction and Arming British Capital Ships (hardback). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 320 pages. ISBN 978-1-59114-027-6.

- Johnston, Ian (2009). Jordan, John (ed.). A Shipyard at war: John Brown & Co. Ltd, Clydebank, 1914–18. Warship 2009. London: Conway. pp. 96–116. ISBN 978-1-84486-089-0.

- Johnston, Ian (2015). Ships for All Nations : John Brown & Company, Clydebank 1847-1971. Seaforth Publishing. In succession to first edition in 2000.

- Johnston, Ronald (2000). Clydeside capital, 1870–1920: a social history of employers.

- McKinstry, Sam (1998). "Transforming John Brown's Shipyard: The Drilling Rig and Offshore Fabrication Business of Marathon". Scottish Economic and Social History. 18 (1): 33–60. doi:10.3366/sesh.1998.18.1.33.

- Peebles, Hugh B (1987). Warshipbuilding on the Clyde: Naval Orders & the Prosperity of Clyde Shipbuilding Industry, 1889–1939.

- Shields, John (1949). Clyde built: a history of ship-building on the River Clyde.

- Slaven, A (July 1977). "A Shipyard in Depression: John Browns of Clydebank 1919–1938". Business History. 19 (2): 192–218. doi:10.1080/00076797700000025.

External links

- "The Story of the Clyde Bank Shipyard". Shipping Times. 30 November 1997.

- Chris' Cunard Page

- Clyde-built ships database — ships and shipbuilders on the River Clyde

- Clydebank Re-built Ltd. — regeneration of Clydebank; in particular, redevelopment of the riverfront areas previously given over to shipbuilding and marine engineering

- Clydebank Restoration Trust

- Clyde Waterfront Heritage — John Brown's Shipyard[permanent dead link]

- Post-Blitz Clydebank — documentary about Clydebank from 1947 to 1952

- Clydebank Through A Lens — documentary about Clydebank from the 1960s to the 1980s

- Documents and clippings about John Brown & Company in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW