Cleveland Guardians

| Cleveland Guardians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| |||||

| Name | |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (2) | |||||

| AL Pennants (6) | |||||

| AL Central Division titles (12) | |||||

| Wild card berths (2) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Larry Dolan | ||||

| President | Paul Dolan (Chairman / CEO) | ||||

| President of baseball operations | Chris Antonetti | ||||

| General manager | Mike Chernoff | ||||

| Manager | Stephen Vogt | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/guardians | ||||

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central Division. Since 1994, the team has played its home games at Progressive Field (originally known as Jacobs Field after the team's then-owner). Since their establishment as a Major League franchise in 1901, the team has won 12 Central Division titles, six American League pennants, and two World Series championships (in 1920 and 1948). The team's World Series championship drought since 1948 is the longest active among all 30 current Major League teams.[2][3] The team's name references the Guardians of Traffic, eight monolithic 1932 Art Deco sculptures by Henry Hering on the city's Hope Memorial Bridge,[4] which is adjacent to Progressive Field.[5][6] The team's mascot is named "Slider".[7] The team's spring training facility is at Goodyear Ballpark in Goodyear, Arizona.[8]

The franchise originated in 1894 as the Grand Rapids Rustlers, a minor league team based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, that played in the Western League. The team relocated to Cleveland in 1900 and was called the Cleveland Lakeshores.[9] The Western League itself was renamed the American League prior to the 1900 season while continuing its minor league status. When the American League declared itself a major league in 1901, Cleveland was one of its eight charter franchises. Originally called the Cleveland Bluebirds or Blues, the team was also unofficially called the Cleveland Broncos in 1902. Beginning in 1903, the team was named the Cleveland Napoleons or Naps, after team captain and manager Nap Lajoie.

Lajoie left after the 1914 season, and club owner Charles Somers requested that baseball writers choose a new name. They chose the name Cleveland Indians.[10][11] That name stuck and remained in use for more than a century. Common nicknames for the Indians were "the Tribe" and "the Wahoos", the latter referencing their longtime logo, Chief Wahoo. After the Indians name came under criticism as part of the Native American mascot controversy, the team adopted the current name (Guardians) following the 2021 season.[5][12][13][14][15]

From August 24 to September 14, 2017, the team won 22 consecutive games, the longest winning streak in American League history and the second longest winning streak in Major League Baseball history.

As of the end of the 2024 season, the franchise's overall record is 9,852–9,369 (.513).[16]

Early Cleveland baseball teams

According to one historian of baseball, "in 1857, baseball games were a daily spectacle in Cleveland's Public Squares. City authorities tried to find an ordinance forbidding it; to the joy of the crowd, they were unsuccessful."[17]

1865–1872 Forest Citys of Cleveland

From 1865 to 1868 Forest Citys was an amateur ball club. During the 1869 season, Cleveland was among several cities that established professional baseball teams following the success of the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first fully professional team.[18][19] In the newspapers before and after 1870, the team was often called the Forest Citys, in the same generic way that the team from Chicago was sometimes called The Chicagos.

In 1871 the Forest Citys joined the new National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NA), the first professional league. Ultimately, two of the league's western clubs went out of business during the first season and the Chicago Fire left that city's White Stockings impoverished, unable to field a team again until 1874. Cleveland was thus the NA's westernmost outpost in 1872, the year the club folded. Cleveland played its full schedule to July 19 followed by two games versus Boston in mid-August and disbanded at the end of the season.[20]

1879–1884 Cleveland Forest Citys and Blues

In 1876, the National League (NL) supplanted the NA as the major professional league. Cleveland was not among its charter members, but by 1879 the league was looking for new entries and the city gained an NL team. A new Cleveland Forest Citys were recreated, but by 1882 were known as the Cleveland Blues, because the National League required distinct colors for that season. The Blues had mediocre records for six seasons and were ruined by a trade war with the Union Association (UA) in 1884, when its three best players (Fred Dunlap, Jack Glasscock, and Jim McCormick) jumped to the UA after being offered higher salaries. The Cleveland Blues merged with the St. Louis Maroons UA team in 1885.

1887–1899 Cleveland Spiders (nicknamed "Blues")

Cleveland went without major league baseball for two seasons until gaining a team in the American Association (AA) in 1887. After the AA's Pittsburgh Alleghenys jumped to the NL, Cleveland followed suit in 1889, as the AA began to crumble. The Cleveland ball club, called the Spiders (supposedly inspired by their "skinny and spindly" players), slowly became a power in the league.[21] In 1891, the Spiders moved into League Park, which would serve as the home of Cleveland professional baseball for the next 55 years. Led by native Ohioan Cy Young, the Spiders became a contender in the mid-1890s, playing in the Temple Cup Series (that era's World Series) twice and winning it in 1895. The team began to fade after this success, and was dealt a severe blow under the ownership of the Robison brothers.

Prior to the 1899 season, Frank Robison, the Spiders' owner, bought the St. Louis Browns, thus owning two clubs at the same time. The Browns were renamed the "Perfectos", and restocked with Cleveland talent. Just weeks before the season opener, most of the better Spiders were transferred to St. Louis, including three future Hall of Famers: Cy Young, Jesse Burkett and Bobby Wallace.[22] The roster maneuvers failed to create a powerhouse Perfectos team, as St. Louis finished fifth in both 1899 and 1900. The Spiders were left with essentially a minor league lineup, and began to lose games at a record pace. Drawing almost no fans at home, they ended up playing most of their season on the road, and became known as "The Wanderers".[23] The team ended the season in 12th place, 84 games out of first place, with an all-time worst record of 20–134 (.130 winning percentage).[24] Following the 1899 season, the National League disbanded four teams, including the Spiders franchise. The disastrous 1899 season would actually be a step toward a new future for Cleveland fans the next year.

1890 Cleveland Infants (nickname "Babes")

The Cleveland Infants competed in the Players' League, which was well-attended in some cities, but club owners lacked the confidence to continue beyond the one season. The Cleveland Infants finished with 55 wins and 75 losses, playing their home games at Brotherhood Park.[25]

History

1894–1935: Beginning to middle

The origins of the Cleveland Guardians date back to 1894, when the team was founded as the Grand Rapids Rustlers, a team based in Grand Rapids, Michigan and competing in the Western League.[9][26][27] In 1900, the team moved to Cleveland and was named the Cleveland Lake Shores. Around the same time Ban Johnson changed the name of his minor league (Western League) to the American League. In 1900 the American League was still considered a minor league. In 1901 the team was called the Cleveland Bluebirds or Blues when the American League broke with the National Agreement and declared itself a competing Major League. The Cleveland franchise was among its eight charter members, and is one of four teams that remain in its original city, along with Boston, Chicago, and Detroit.

The new team was owned by coal magnate Charles Somers and tailor Jack Kilfoyl. Somers, a wealthy industrialist and also co-owner of the Boston Americans, lent money to other team owners, including Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics, to keep them and the new league afloat. Players did not think the name "Bluebirds" was suitable for a baseball team.[28] Writers frequently shortened it to Cleveland Blues due to the players' all-blue uniforms,[29] but the players did not like this unofficial name either.[30] The players themselves tried to change the name to Cleveland Bronchos in 1902, but this name never caught on.[28]

Cleveland suffered from financial problems in their first two seasons. This led Somers to seriously consider moving to either Pittsburgh or Cincinnati. Relief came in 1902 as a result of the conflict between the National and American Leagues. In 1901, Napoleon "Nap" Lajoie, the Philadelphia Phillies' star second baseman, jumped to the A's after his contract was capped at $2,400 per year—one of the highest-profile players to jump to the upstart AL. The Phillies subsequently filed an injunction to force Lajoie's return, which was granted by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The injunction appeared to doom any hopes of an early settlement between the warring leagues. However, a lawyer discovered that the injunction was only enforceable in the state of Pennsylvania.[28] Mack, partly to thank Somers for his past financial support, agreed to trade Lajoie to the then-moribund Blues, who offered $25,000 salary over three years.[31] Due to the injunction, however, Lajoie had to sit out any games played against the A's in Philadelphia.[32] Lajoie arrived in Cleveland on June 4 and was an immediate hit, drawing 10,000 fans to League Park. Soon afterward, he was named team captain, and in 1903 the team was called the Cleveland Napoleons or Naps after a newspaper conducted a write-in contest.[28]

Lajoie was named manager in 1905, and the team's fortunes improved somewhat. They finished half a game short of the pennant in 1908.[33] However, the success did not last and Lajoie resigned during the 1909 season as manager but remained on as a player.[34]

After that, the team began to unravel, leading Kilfoyl to sell his share of the team to Somers. Cy Young, who returned to Cleveland in 1909, was ineffective for most of his three remaining years[35] and Addie Joss died from tubercular meningitis prior to the 1911 season.[36]

Despite a strong lineup anchored by the potent Lajoie and Shoeless Joe Jackson, poor pitching kept the team below third place for most of the next decade. One reporter referred to the team as the Napkins, "because they fold up so easily". The team hit bottom in 1914 and 1915, finishing last place both years.[37][38]

1915 brought significant changes to the team. Lajoie, nearly 40 years old, was no longer a top hitter in the league, batting only .258 in 1914. With Lajoie engaged in a feud with manager Joe Birmingham, the team sold Lajoie back to the A's.[39]

With Lajoie gone, the club needed a new name. Somers asked the local baseball writers to come up with a new name, and based on their input, the team was renamed the Cleveland Indians.[40] The name referred to the nickname "Indians" that was applied to the Cleveland Spiders baseball club during the time when Louis Sockalexis, a Native American, played in Cleveland (1897–1899).[41]

At the same time, Somers' business ventures began to fail, leaving him deeply in debt. With the Indians playing poorly, attendance and revenue suffered.[42] Somers decided to trade Jackson midway through the 1915 season for two players and $31,500, one of the largest sums paid for a player at the time.[43]

By 1916, Somers was at the end of his tether, and sold the team to a syndicate headed by Chicago railroad contractor James C. "Jack" Dunn.[42] Manager Lee Fohl, who had taken over in early 1915, acquired two minor league pitchers, Stan Coveleski and Jim Bagby and traded for center fielder Tris Speaker, who was engaged in a salary dispute with the Red Sox.[44] All three would ultimately become key players in bringing a championship to Cleveland.

Speaker took over the reins as player-manager in 1919, and led the team to a championship in 1920. On August 16, 1920, the Indians were playing the Yankees at the Polo Grounds in New York. Shortstop Ray Chapman, who often crowded the plate, was batting against Carl Mays, who had an unusual underhand delivery. It was also late in the afternoon and the infield was completely shaded with the center field area (the batters' background) bathed in sunlight. As well, at the time, "part of every pitcher's job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field. By turns, they smeared it with dirt, licorice, tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred, cut, even spiked. The result was a misshapen, earth-colored ball that traveled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and as it came over the plate, was very hard to see."[45]

In any case, Chapman did not move reflexively when Mays' pitch came his way. The pitch hit Chapman in the head, fracturing his skull. Chapman died the next day, becoming the only player to sustain a fatal injury from a pitched ball.[46] The Indians, who at the time were locked in a tight three-way pennant race with the Yankees and White Sox,[47] were not slowed down by the death of their teammate. Rookie Joe Sewell hit .329 after replacing Chapman in the lineup.[48]

In September 1920, the Black Sox Scandal came to a boil. With just a few games left in the season, and Cleveland and Chicago neck-and-neck for first place at 94–54 and 95–56 respectively,[49][50] the Chicago owner suspended eight players. The White Sox lost two of three in their final series, while Cleveland won four and lost two in their final two series. Cleveland finished two games ahead of Chicago and three games ahead of the Yankees to win its first pennant, led by Speaker's .388 hitting, Jim Bagby's 30 victories and solid performances from Steve O'Neill and Stan Coveleski. Cleveland went on to defeat the Brooklyn Robins 5–2 in the World Series for their first title, winning four games in a row after the Robins took a 2–1 Series lead. The Series included three memorable "firsts", all of them in Game 5 at Cleveland, and all by the home team. In the first inning, right fielder Elmer Smith hit the first Series grand slam. In the fourth inning, Jim Bagby hit the first Series home run by a pitcher. In the top of the fifth inning, second baseman Bill Wambsganss executed the first (and only, so far) unassisted triple play in World Series history, in fact, the only Series triple play of any kind.

The team would not reach the heights of 1920 again for 28 years. Speaker and Coveleski were aging and the Yankees were rising with a new weapon: Babe Ruth and the home run. They managed two second-place finishes but spent much of the decade in last place. In 1927 Dunn's widow, Mrs. George Pross (Dunn had died in 1922), sold the team to a syndicate headed by Alva Bradley.

1936–1946: Bob Feller enters the show

The Indians were a middling team by the 1930s, finishing third or fourth most years. 1936 brought Cleveland a new superstar in 17-year-old pitcher Bob Feller, who came from Iowa with a dominating fastball. That season, Feller set a record with 17 strikeouts in a single game and went on to lead the league in strikeouts from 1938 to 1941.

On August 20, 1938, Indians catchers Hank Helf and Frank Pytlak set the "all-time altitude mark" by catching baseballs dropped from the 708-foot (216 m) Terminal Tower.[51]

By 1940, Feller, along with Ken Keltner, Mel Harder and Lou Boudreau, led the Indians to within one game of the pennant. However, the team was wracked with dissension, with some players (including Feller and Mel Harder) going so far as to request that Bradley fire manager Ossie Vitt. Reporters lampooned them as the Cleveland Crybabies.[52][better source needed] Feller, who had pitched a no-hitter to open the season and won 27 games, lost the final game of the season to unknown pitcher Floyd Giebell of the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers won the pennant and Giebell never won another major league game.[53]

Cleveland entered 1941 with a young team and a new manager; Roger Peckinpaugh had replaced the despised Vitt; but the team regressed, finishing in fourth. Cleveland would soon be depleted of two stars. Hal Trosky retired in 1941 due to migraine headaches[54] and Bob Feller enlisted in the Navy two days after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. Starting third baseman Ken Keltner and outfielder Ray Mack were both drafted in 1945 taking two more starters out of the lineup.[55]

1946–1949: The Bill Veeck years

In 1946, Bill Veeck formed an investment group that purchased the Cleveland Indians from Bradley's group for a reported $1.6 million.[56] Among the investors was Bob Hope, who had grown up in Cleveland, and former Tigers slugger, Hank Greenberg.[57] A former owner of a minor league franchise in Milwaukee, Veeck brought to Cleveland a gift for promotion. At one point, Veeck hired rubber-faced[58] Max Patkin, the "Clown Prince of Baseball" as a coach. Patkin's appearance in the coaching box was the sort of promotional stunt that delighted fans but infuriated the American League front office.

Recognizing that he had acquired a solid team, Veeck soon abandoned the aging, small and lightless League Park to take up full-time residence in massive Cleveland Municipal Stadium.[59] The Indians had briefly moved from League Park to Municipal Stadium in mid-1932, but moved back to League Park due to complaints about the cavernous environment. From 1937 onward, however, the Indians began playing an increasing number of games at Municipal, until by 1940 they played most of their home slate there.[60] League Park was mostly demolished in 1951, but has since been rebuilt as a recreational park.[61]

Making the most of the cavernous stadium, Veeck had a portable center field fence installed, which he could move in or out depending on how the distance favored the Indians against their opponents in a given series. The fence moved as much as 15 feet (5 m) between series opponents. Following the 1947 season, the American League countered with a rule change that fixed the distance of an outfield wall for the duration of a season. The massive stadium did, however, permit the Indians to set the then-record for the largest crowd to see a Major League baseball game. On October 10, 1948, Game 5 of the World Series against the Boston Braves drew over 84,000. The record stood until the Los Angeles Dodgers drew a crowd in excess of 92,500 to watch Game 5 of the 1959 World Series at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum against the Chicago White Sox.

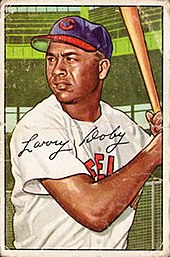

Under Veeck's leadership, one of Cleveland's most significant achievements was breaking the color barrier in the American League by signing Larry Doby, formerly a player for the Negro league's Newark Eagles in 1947, 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers.[59] Similar to Robinson, Doby battled racism on and off the field but posted a .301 batting average in 1948, his first full season. A power-hitting center fielder, Doby led the American League twice in homers.

In 1948, needing pitching for the stretch run of the pennant race, Veeck turned to the Negro leagues again and signed pitching great Satchel Paige amid much controversy.[59] Barred from Major League Baseball during his prime, Veeck's signing of the aging star in 1948 was viewed by many as another publicity stunt. At an official age of 42, Paige became the oldest rookie in Major League baseball history, and the first black pitcher. Paige ended the year with a 6–1 record with a 2.48 ERA, 45 strikeouts and two shutouts.[62]

In 1948, veterans Boudreau, Keltner, and Joe Gordon had career offensive seasons, while newcomers Doby and Gene Bearden also had standout seasons. The team went down to the wire with the Boston Red Sox, winning a one-game playoff, the first in American League history, to go to the World Series. In the series, the Indians defeated the Boston Braves four games to two for their first championship in 28 years. Boudreau won the American League MVP Award.

The Indians appeared in a film the following year titled The Kid From Cleveland, in which Veeck had an interest.[59] The film portrayed the team helping out a "troubled teenaged fan"[63] and featured many members of the Indians organization. However, filming during the season cost the players valuable rest days leading to fatigue towards the end of the season.[59] That season, Cleveland again contended before falling to third place. On September 23, 1949, Bill Veeck and the Indians buried their 1948 pennant in center field the day after they were mathematically eliminated from the pennant race.[59]

Later in 1949, Veeck's first wife (who had a half-stake in Veeck's share of the team) divorced him. With most of his money tied up in the Indians, Veeck was forced to sell the team[64] to a syndicate headed by insurance magnate Ellis Ryan.

1950–1959: Near misses

In 1953, Al Rosen was an All Star for the second year in a row, was named The Sporting News Major League Player of the Year, and won the American League Most Valuable Player Award in a unanimous vote playing for the Indians after leading the AL in runs, home runs, RBIs (for the second year in a row), and slugging percentage, and coming in second by one point in batting average.[65] Ryan was forced out in 1953 in favor of Myron Wilson, who in turn gave way to William Daley in 1956. Despite this turnover in the ownership, a powerhouse team composed of Feller, Doby, Minnie Miñoso, Luke Easter, Bobby Ávila, Al Rosen, Early Wynn, Bob Lemon, and Mike Garcia continued to contend through the early 1950s. However, Cleveland only won a single pennant in the decade, in 1954, finishing second to the New York Yankees five times.

The winningest season in franchise history came in 1954, when the Indians finished the season with a record of 111–43 (.721). That mark set an American League record for wins that stood for 44 years until the Yankees won 114 games in 1998 (a 162-game regular season). The Indians' 1954 winning percentage of .721 is still an American League record. The Indians returned to the World Series to face the New York Giants. The team could not bring home the title, however, ultimately being upset by the Giants in a sweep. The series was notable for Willie Mays' over-the-shoulder catch off the bat of Vic Wertz in Game 1. Cleveland remained a talented team throughout the remainder of the decade, finishing in second place in 1959, George Strickland's last full year in the majors.

1960–1993: The 33-year slump

From 1960 to 1993, the Indians managed one third-place finish (in 1968) and six fourth-place finishes (in 1960, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1990, and 1992) but spent the rest of the time at or near the bottom of the standings, including four seasons with over 100 losses (1971, 1985, 1987, 1991).

Frank Lane becomes general manager

The Indians hired general manager Frank Lane, known as "Trader" Lane, away from the St. Louis Cardinals in 1957. Lane over the years had gained a reputation as a GM who loved to make deals. With the White Sox, Lane had made over 100 trades involving over 400 players in seven years.[66] In a short stint in St. Louis, he traded away Red Schoendienst and Harvey Haddix.[66] Lane summed up his philosophy when he said that the only deals he regretted were the ones that he did not make.[67]

One of Lane's early trades in Cleveland was to send Roger Maris to the Kansas City Athletics in the middle of 1958. Indians executive Hank Greenberg was not happy about the trade[68] and neither was Maris, who said that he could not stand Lane.[68] After Maris broke Babe Ruth's home run record, Lane defended himself by saying he still would have done the deal because Maris was unknown and he received good ballplayers in exchange.[68]

After the Maris trade, Lane acquired 25-year-old Norm Cash from the White Sox for Minnie Miñoso and then traded him to Detroit before he ever played a game for the Indians; Cash went on to hit over 350 home runs for the Tigers. The Indians received Steve Demeter in the deal, who had only five at-bats for Cleveland.[69]

Curse of Rocky Colavito

In 1960, Lane made the trade that would define his tenure in Cleveland when he dealt slugging right fielder and fan favorite[70] Rocky Colavito to the Detroit Tigers for Harvey Kuenn just before Opening Day in 1960.

It was a blockbuster trade that swapped the 1959 AL home run co-champion (Colavito) for the AL batting champion (Kuenn). After the trade, however, Colavito hit over 30 home runs four times and made three All-Star teams for Detroit and Kansas City before returning to Cleveland in 1965. Kuenn, on the other hand, played only one season for the Indians before departing for San Francisco in a trade for an aging Johnny Antonelli and Willie Kirkland. Akron Beacon Journal columnist Terry Pluto documented the decades of woe that followed the trade in his book The Curse of Rocky Colavito.[71] Despite being attached to the curse, Colavito said that he never placed a curse on the Indians but that the trade was prompted by a salary dispute with Lane.[72]

Lane also engineered a unique trade of managers in mid-season 1960, sending Joe Gordon to the Tigers in exchange for Jimmy Dykes. Lane left the team in 1961, but ill-advised trades continued. In 1965, the Indians traded pitcher Tommy John, who would go on to win 288 games in his career, and 1966 Rookie of the Year Tommy Agee to the White Sox to get Colavito back.[72]

However, Indians' pitchers set numerous strikeout records. They led the league in K's every year from 1963 to 1968, and narrowly missed in 1969. The 1964 staff was the first to amass 1,100 strikeouts, and in 1968, they were the first to collect more strikeouts than hits allowed.

Move to the AL East division

The 1970s were not much better, with the Indians trading away several future stars, including Graig Nettles, Dennis Eckersley, Buddy Bell and 1971 Rookie of the Year Chris Chambliss,[73] for a number of players who made no impact.[74]

Constant ownership changes did not help the Indians. In 1963, Daley's syndicate sold the team to a group headed by general manager Gabe Paul.[28] Three years later, Paul sold the Indians to Vernon Stouffer,[75] of the Stouffer's frozen-food empire. Prior to Stouffer's purchase, the team was rumored to be relocated due to poor attendance. Despite the potential for a financially strong owner, Stouffer had some non-baseball related financial setbacks and, consequently, the team was cash-poor. In order to solve some financial problems, Stouffer had made an agreement to play a minimum of 30 home games in New Orleans with a view to a possible move there.[76] After rejecting an offer from George Steinbrenner and former Indian Al Rosen, Stouffer sold the team in 1972 to a group led by Cleveland Cavaliers and Cleveland Barons owner Nick Mileti.[76] Steinbrenner went on to buy the New York Yankees in 1973.[77]

Only five years later, Mileti's group sold the team for $11 million to a syndicate headed by trucking magnate Steve O'Neill and including former general manager and owner Gabe Paul.[78] O'Neill's death in 1983 led to the team going on the market once more. O'Neill's nephew Patrick O'Neill did not find a buyer until real estate magnates Richard and David Jacobs purchased the team in 1986.[79]

The team was unable to move out of last place, with losing seasons between 1969 and 1975. One highlight was the acquisition of Gaylord Perry in 1972. The Indians traded fireballer "Sudden Sam" McDowell for Perry, who became the first Indian pitcher to win the Cy Young Award. In 1975, Cleveland broke another color barrier with the hiring of Frank Robinson as Major League Baseball's first African American manager. Robinson served as player-manager and provided a franchise highlight when he hit a pinch-hit home run on Opening Day. But the high-profile signing of Wayne Garland, a 20-game winner in Baltimore, proved to be a disaster after Garland suffered from shoulder problems and went 28–48 over five years.[80] The team failed to improve with Robinson as manager and he was fired in 1977. In 1977, pitcher Dennis Eckersley threw a no-hitter against the California Angels. The next season, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox where he won 20 games in 1978 and another 17 in 1979.

The 1970s also featured the infamous Ten Cent Beer Night at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. The ill-conceived promotion at a 1974 game against the Texas Rangers ended in a riot by fans and a forfeit by the Indians.[81]

There were more bright spots in the 1980s. In May 1981, Len Barker threw a perfect game against the Toronto Blue Jays, joining Addie Joss as the only other Indian pitcher to do so.[82] "Super Joe" Charboneau won the American League Rookie of the Year award. Unfortunately, Charboneau was out of baseball by 1983 after falling victim to back injuries[83] and Barker, who was also hampered by injuries, never became a consistently dominant starting pitcher.[82]

Eventually, the Indians traded Barker to the Atlanta Braves for Brett Butler and Brook Jacoby,[82] who became mainstays of the team for the remainder of the decade. Butler and Jacoby were joined by Joe Carter, Mel Hall, Julio Franco and Cory Snyder, bringing new hope to fans in the late 1980s.[84]

Cleveland's struggles over the 30-year span were highlighted in the 1989 film Major League, which comically depicted a hapless Cleveland ball club going from worst to first by the end of the film.

Throughout the 1980s, the Indians' owners had pushed for a new stadium. Cleveland Stadium had been a symbol of the Indians' glory years in the 1940s and 1950s.[85] However, during the lean years even crowds of 40,000 were swallowed up by the cavernous environment. The old stadium was not aging gracefully; chunks of concrete were falling off in sections and the old wooden pilings were petrifying.[86] In 1984, a proposal for a $150 million domed stadium was defeated in a referendum 2–1.[87]

Finally, in May 1990, Cuyahoga County voters passed an excise tax on sales of alcohol and cigarettes in the county. The tax proceeds were to be used for financing the construction of the Gateway Sports and Entertainment Complex, which would include Jacobs Field for the Indians and Gund Arena for the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team.[88]

The team's fortunes started to turn in 1989, ironically with a very unpopular trade. The team sent power-hitting outfielder Joe Carter to the San Diego Padres for two unproven players, Sandy Alomar Jr. and Carlos Baerga. Alomar made an immediate impact, not only being elected to the All-Star team but also winning Cleveland's fourth Rookie of the Year award and a Gold Glove. Baerga became a three-time All-Star with consistent offensive production.

Indians general manager John Hart made a number of moves that finally brought success to the team. In 1991, he hired former Indian Mike Hargrove to manage and traded catcher Eddie Taubensee to the Houston Astros who, with a surplus of outfielders, were willing to part with Kenny Lofton. Lofton finished second in AL Rookie of the Year balloting with a .285 average and 66 stolen bases.

The Indians were named "Organization of the Year" by Baseball America[89] in 1992, in response to the appearance of offensive bright spots and an improving farm system.

The team suffered a tragedy during spring training of 1993, when a boat carrying pitchers Steve Olin, Tim Crews, and Bob Ojeda crashed into a pier. Olin and Crews were killed, and Ojeda was seriously injured. (Ojeda missed most of the season, and retired the following year).[90]

By the end of the 1993 season, the team was in transition, leaving Cleveland Stadium and fielding a talented nucleus of young players. Many of those players came from the Indians' new AAA farm team, the Charlotte Knights, who won the International League title that year.

1994–2001: New beginnings

1994: Jacobs Field opens

Indians General Manager John Hart and team owner Richard Jacobs managed to turn the team's fortunes around. The Indians opened Jacobs Field in 1994 with the aim of improving on the prior season's sixth-place finish. The Indians were only one game behind the division-leading Chicago White Sox on August 12 when a players strike wiped out the rest of the season.

1995–1996: First AL pennant since 1954

Having contended for the division in the aborted 1994 season, Cleveland sprinted to a 100–44 record (the season was shortened by 18 games due to player/owner negotiations) in 1995, winning its first-ever divisional title. Veterans Dennis Martínez, Orel Hershiser and Eddie Murray combined with a young core of players including Omar Vizquel, Albert Belle, Jim Thome, Manny Ramírez, Kenny Lofton and Charles Nagy to lead the league in team batting average as well as team ERA.

After defeating the Boston Red Sox in the Division Series and the Seattle Mariners in the ALCS, Cleveland clinched the American League pennant and a World Series berth, for the first time since 1954. The World Series ended in disappointment, however: the Indians fell in six games to the Atlanta Braves.

Tickets for every Indians home game sold out several months before opening day in 1996.[91] The Indians repeated as AL Central champions but lost to the wild card Baltimore Orioles in the Division Series.

1997: Two outs away

In 1997, Cleveland started slow but finished with an 86–75 record. Taking their third consecutive AL Central title, the Indians defeated the New York Yankees in the Division Series, 3–2. After defeating the Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS, Cleveland went on to face the Florida Marlins in the World Series that featured the coldest game in World Series history. With the series tied after Game 6, the Indians went into the ninth inning of Game Seven with a 2–1 lead, but closer José Mesa allowed the Marlins to tie the game. In the eleventh inning, Édgar Rentería drove in the winning run giving the Marlins their first championship. Cleveland became the first team to lose the World Series after carrying the lead into the ninth inning of the seventh game.[92]

1998–2001

In 1998, the Indians made the postseason for the fourth straight year. After defeating the wild-card Boston Red Sox 3–1 in the Division Series, Cleveland lost the 1998 ALCS in six games to the New York Yankees, who had come into the postseason with a then-AL record 114 wins in the regular season.[93]

For the 1999 season, Cleveland added relief pitcher Ricardo Rincón and second baseman Roberto Alomar, brother of catcher Sandy Alomar Jr.,[94] and won the Central Division title for the fifth consecutive year. The team scored 1,009 runs, becoming the first (and to date only) team since the 1950 Boston Red Sox to score more than 1,000 runs in a season. This time, Cleveland did not make it past the first round, losing the Division Series to the Red Sox, despite taking a 2–0 lead in the series. In game three, Indians starter Dave Burba went down with an injury in the 4th inning.[95] Four pitchers, including presumed game four starter Jaret Wright, surrendered nine runs in relief. Without a long reliever or emergency starter on the playoff roster, Hargrove started both Bartolo Colón and Charles Nagy in games four and five on only three days rest.[95] The Indians lost game four 23–7 and game five 12–8.[96] Four days later, Hargrove was dismissed as manager.[97]

In 2000, the Indians had a 44–42 start, but caught fire after the All Star break and went 46–30 the rest of the way to finish 90–72.[98] The team had one of the league's best offenses that year and a defense that yielded three gold gloves. However, they ended up five games behind the Chicago White Sox in the Central division and missed the wild card by one game to the Seattle Mariners. Mid-season trades brought Bob Wickman and Jake Westbrook to Cleveland. After the season, free-agent outfielder Manny Ramírez departed for the Boston Red Sox.

In 2000, Larry Dolan bought the Indians for $320 million from Richard Jacobs, who, along with his late brother David, had paid $45 million for the club in 1986. The sale set a record at the time for the sale of a baseball franchise.[99]

2001 saw a return to the postseason. After the departures of Ramírez and Sandy Alomar Jr., the Indians signed Ellis Burks and former MVP Juan González, who helped the team win the Central division with a 91–71 record. One of the highlights came on August 5, when the Indians completed the biggest comeback in MLB History. Cleveland rallied to close a 14–2 deficit in the seventh inning to defeat the Seattle Mariners 15–14 in 11 innings. The Mariners, who won an MLB record-tying 116 games that season, had a strong bullpen, and Indians manager Charlie Manuel had already pulled many of his starters with the game seemingly out of reach.

Seattle and Cleveland met in the first round of the postseason; however, the Mariners won the series 3–2. In the 2001–02 offseason, GM John Hart resigned and his assistant, Mark Shapiro, took the reins.

2002–2010: The Shapiro/Wedge years

First "rebuilding of the team"

Shapiro moved to rebuild by dealing aging veterans for younger talent. He traded Roberto Alomar to the New York Mets for a package that included outfielder Matt Lawton and prospects Alex Escobar and Billy Traber. When the team fell out of contention in mid-2002, Shapiro fired manager Charlie Manuel and traded pitching ace Bartolo Colón for prospects Brandon Phillips, Cliff Lee, and Grady Sizemore; acquired Travis Hafner from the Rangers for Ryan Drese and Einar Díaz; and picked up Coco Crisp from the St. Louis Cardinals for aging starter Chuck Finley. Jim Thome left after the season, going to the Phillies for a larger contract.

Young Indians teams finished far out of contention in 2002 and 2003 under new manager Eric Wedge. They posted strong offensive numbers in 2004, but continued to struggle with a bullpen that blew more than 20 saves. A highlight of the season was a 22–0 victory over the New York Yankees on August 31, one of the worst defeats suffered by the Yankees in team history.[100]

In early 2005, the offense got off to a poor start. After a brief July slump, the Indians caught fire in August, and cut a 15.5 game deficit in the Central Division down to 1.5 games. However, the season came to an end as the Indians went on to lose six of their last seven games, five of them by one run, missing the playoffs by only two games. Shapiro was named Executive of the Year in 2005.[101] The next season, the club made several roster changes, while retaining its nucleus of young players. The off-season was highlighted by the acquisition of top prospect Andy Marte from the Boston Red Sox. The Indians had a solid offensive season, led by career years from Travis Hafner and Grady Sizemore. Hafner, despite missing the last month of the season, tied the single season grand slam record of six, which was set in 1987 by Don Mattingly.[102] Despite the solid offensive performance, the bullpen struggled with 23 blown saves (a Major League worst), and the Indians finished a disappointing fourth.[103]

In 2007, Shapiro signed veteran help for the bullpen and outfield in the offseason. Veterans Aaron Fultz and Joe Borowski joined Rafael Betancourt in the Indians bullpen.[104] The Indians improved significantly over the prior year and went into the All-Star break in second place. The team brought back Kenny Lofton for his third stint with the team in late July.[105] The Indians finished with a 96–66 record tied with the Red Sox for best in baseball, their seventh Central Division title in 13 years and their first postseason trip since 2001.[106]

The Indians began their playoff run by defeating the Yankees in the ALDS three games to one. This series will be most remembered for the swarm of bugs that overtook the field in the later innings of Game Two. They also jumped out to a three-games-to-one lead over the Red Sox in the ALCS. The season ended in disappointment when Boston swept the final three games to advance to the 2007 World Series.[106]

Despite the loss, Cleveland players took home a number of awards. Grady Sizemore, who had a .995 fielding percentage and only two errors in 405 chances, won the Gold Glove award, Cleveland's first since 2001.[107] Indians Pitcher CC Sabathia won the second Cy Young Award in team history with a 19–7 record, a 3.21 ERA and an MLB-leading 241 innings pitched.[108] Eric Wedge was awarded the first Manager of the Year Award in team history.[109] Shapiro was named to his second Executive of the Year in 2007.[101]

Second "rebuilding of the team"

The Indians struggled during the 2008 season. Injuries to sluggers Travis Hafner and Victor Martinez, as well as starting pitchers Jake Westbrook and Fausto Carmona led to a poor start.[110] The Indians, falling to last place for a short time in June and July, traded CC Sabathia to the Milwaukee Brewers for prospects Matt LaPorta, Rob Bryson, and Michael Brantley.[111] and traded starting third baseman Casey Blake for catching prospect Carlos Santana.[112] Pitcher Cliff Lee went 22–3 with an ERA of 2.54 and earned the AL Cy Young Award.[113] Grady Sizemore had a career year, winning a Gold Glove Award and a Silver Slugger Award,[114] and the Indians finished with a record of 81–81.

Prospects for the 2009 season dimmed early when the Indians ended May with a record of 22–30. Shapiro made multiple trades: Cliff Lee and Ben Francisco to the Philadelphia Phillies for prospects Jason Knapp, Carlos Carrasco, Jason Donald and Lou Marson; Victor Martinez to the Boston Red Sox for prospects Bryan Price, Nick Hagadone and Justin Masterson; Ryan Garko to the Texas Rangers for Scott Barnes; and Kelly Shoppach to the Tampa Bay Rays for Mitch Talbot. The Indians finished the season tied for fourth in their division, with a record of 65–97. The team announced on September 30, 2009, that Eric Wedge and all of the team's coaching staff were released at the end of the 2009 season.[115] Manny Acta was hired as the team's 40th manager on October 25, 2009.[116]

On February 18, 2010, it was announced that Shapiro (following the end of the 2010 season) would be promoted to team President, with current President Paul Dolan becoming the new Chairman/CEO, and longtime Shapiro assistant Chris Antonetti filling the GM role.[117]

2011–present: Antonetti/Chernoff/Francona era

On January 18, 2011, longtime popular former first baseman and manager Mike Hargrove was brought in as a special adviser. The Indians started the 2011 season strong – going 30–15 in their first 45 games and seven games ahead of the Detroit Tigers for first place. Injuries led to a slump where the Indians fell out of first place. Many minor leaguers such as Jason Kipnis and Lonnie Chisenhall got opportunities to fill in for the injuries.[118] The biggest news of the season came on July 30 when the Indians traded four prospects for Colorado Rockies star pitcher, Ubaldo Jiménez. The Indians sent their top two pitchers in the minors, Alex White and Drew Pomeranz along with Joe Gardner and Matt McBride.[119] On August 25, the Indians signed the team leader in home runs, Jim Thome off of waivers.[120] He made his first appearance in an Indians uniform since he left Cleveland after the 2002 season. To honor Thome, the Indians placed him at his original position, third base, for one pitch against the Minnesota Twins on September 25. It was his first appearance at third base since 1996, and his last for Cleveland.[121] The Indians finished the season in 2nd place, 15 games behind the division champion Tigers.[122]

The Indians broke Progressive Field's Opening Day attendance record with 43,190 against the Toronto Blue Jays on April 5, 2012. The game went 16 innings, setting the MLB Opening Day record, and lasted 5 hours and 14 minutes.[123]

On September 27, 2012, with six games left in the Indians' 2012 season, Manny Acta was fired; Sandy Alomar Jr. was named interim manager for the remainder of the season.[124] On October 6, the Indians announced that Terry Francona, who managed the Boston Red Sox to five playoff appearances and two World Series between 2004 and 2011, would take over as manager for 2013.[125]

The Indians entered the 2013 season following an active offseason of dramatic roster turnover. Key acquisitions included free agent 1B/OF Nick Swisher and CF Michael Bourn.[126] The team added prized right-handed pitching prospect Trevor Bauer, OF Drew Stubbs, and relief pitchers Bryan Shaw and Matt Albers in a three-way trade with the Arizona Diamondbacks and Cincinnati Reds that sent RF Shin-Soo Choo to the Reds, and Tony Sipp to the Arizona Diamondbacks[127] Other notable additions included utility man Mike Avilés, catcher Yan Gomes, designated hitter Jason Giambi, and starting pitcher Scott Kazmir.[126][128] The 2013 Indians increased their win total by 24 over 2012 (from 68 to 92), finishing in second place, one game behind Detroit in the Central division, but securing the number one seed in the American League Wild Card Standings. In their first postseason appearance since 2007, Cleveland lost the 2013 American League Wild Card Game 4–0 at home to Tampa Bay. Francona was recognized for the turnaround with the 2013 American League Manager of the Year Award.

With an 85–77 record, the 2014 Indians had consecutive winning seasons for the first time since 1999–2001, but they were eliminated from playoff contention during the last week of the season and finished third in the AL Central.

In 2015, after struggling through the first half of the season, the Indians finished 81–80 for their third consecutive winning season, which the team had not done since 1999–2001. For the second straight year, the Tribe finished third in the Central and was eliminated from the Wild Card race during the last week of the season. Following the departure of longtime team executive Mark Shapiro on October 6, the Indians promoted GM Chris Antonetti to President of Baseball Operations, assistant general manager Mike Chernoff to GM, and named Derek Falvey as assistant GM.[129] Falvey was later hired by the Minnesota Twins in 2016, becoming their President of Baseball Operations.

The Indians set what was then a franchise record for longest winning streak when they won their 14th consecutive game, a 2–1 win over the Toronto Blue Jays in 19 innings on July 1, 2016, at Rogers Centre.[130][131] The team clinched the Central Division pennant on September 26, their eighth division title overall and first since 2007, as well as returning to the playoffs for the first time since 2013. They finished the regular season at 94–67, marking their fourth straight winning season, a feat not accomplished since the 1990s and early 2000s.

The Indians began the 2016 postseason by sweeping the Boston Red Sox in the best-of-five American League Division Series, then defeated the Blue Jays in five games in the 2016 American League Championship Series to claim their sixth American League pennant and advance to the World Series against the Chicago Cubs. It marked the first appearance for the Indians in the World Series since 1997 and first for the Cubs since 1945. The Indians took a 3–1 series lead following a victory in Game 4 at Wrigley Field, but the Cubs rallied to take the final three games and won the series 4 games to 3. The Indians' 2016 success led to Francona winning his second AL Manager of the Year Award with the club.

From August 24 through September 15 during the 2017 season, the Indians set a new American League record by winning 22 games in a row.[132] On September 28, the Indians won their 100th game of the season, marking only the third time in history the team has reached that milestone. They finished the regular season with 102 wins, second-most in team history (behind 1954's 111 win team). The Indians earned the AL Central title for the second consecutive year, along with home-field advantage throughout the American League playoffs, but they lost the 2017 ALDS to the Yankees 3–2 after being up 2–0.[133]

In 2018, the Indians won their third consecutive AL Central crown with a 91–71 record, but were swept in the 2018 American League Division Series by the Houston Astros, who outscored Cleveland 21–6. In 2019, despite a two-game improvement, the Indians missed the playoffs as they trailed three games behind the Tampa Bay Rays for the second AL Wild Card berth. During the 2020 season (shortened to 60 games because of the COVID-19 pandemic), the Indians were 35–25, finishing second behind the Minnesota Twins in the AL Central, but qualified for the expanded playoffs. In the best-of-three AL Wild Card Series, the Indians were swept by the New York Yankees, ending their season.

Guardians rebranding

On December 18, 2020, the team announced that the Indians name and logo would be dropped after the 2021 season, later revealing the replacement to be the Guardians.[134][14][5][15] In their first season as the Guardians, the team won the 2022 AL Central Division crown, marking the 11th division title in franchise history. In the best-of-three AL Wild Card Series, the Guardians won the series against the Tampa Bay Rays 2–0, to advance to the AL Division Series. The Guardians lost the series to the New York Yankees 3–2, ending their season. In June 2022, sports investor David Blitzer bought a 25% stake in the franchise with an option to acquire controlling interest in 2028.[135][136]

Following Francona's retirement at the end of the 2023 season, the Guardians named Stephen Vogt as their new manager on November 6, 2023.

Season-by-season results

Rivalries

Interleague

The rivalry with fellow Ohio team the Cincinnati Reds is known as the Battle of Ohio or Buckeye Series and features the Ohio Cup trophy for the winner. Prior to 1997, the winner of the cup was determined by an annual pre-season baseball game, played each year at minor-league Cooper Stadium in the state capital of Columbus, and staged just days before the start of each new Major League Baseball season. A total of eight Ohio Cup games were played, with the Guardians winning six of them. It ended with the start of interleague play in 1997. The winner of the game each year was awarded the Ohio Cup in postgame ceremonies. The Ohio Cup was a favorite among baseball fans in Columbus, with attendances regularly topping 15,000.

Since 1997, the two teams have played each other as part of the regular season, with the exception of 2002. The Ohio Cup was reintroduced in 2008 and is presented to the team who wins the most games in the series that season. Initially, the teams played one three-game series per season, meeting in Cleveland in 1997 and Cincinnati the following year. The teams have played two series per season against each other since 1999, with the exception of 2002, one at each ballpark. A format change in 2013 made each series two games, except in years when the AL and NL Central divisions meet in interleague play, where it is usually extended to three games per series.[137] As of 2024, the Guardians lead the series 76-59.[138]

An on-and-off rivalry with the Pittsburgh Pirates stems from the close proximity of the two cities, and features some carryover elements from the longstanding rivalry in the National Football League between the Cleveland Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers. Because the Guardians' designated interleague rival is the Reds and the Pirates' designated rival is the Tigers, the teams have played periodically. The teams played one three-game series each year from 1997 to 2001 and periodically between 2002 and 2022, generally only in years in which the AL Central played the NL Central in the former interleague play rotation. The teams played six games in 2020 as MLB instituted an abbreviated schedule focusing on regional match-ups. Beginning in 2023, the teams will play a three-game series each season as a result of the new "balanced" schedule. The Pirates lead the series 21–18.[139]

Detroit Tigers

As the Guardians play most of their games every year with each of their AL Central competitors (formerly 19 for each team until 2023), several rivalries have developed.

The Guardians have a geographic rivalry with the Detroit Tigers, highlighted in past years by intense battles for the AL Central title. The matchup has some carryover elements from the Ohio State-Michigan rivalry, as well as the general historic rivalry between Michigan and Ohio dating back to the Toledo War.

Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are another rival, dating back to the 1959 season, when the Sox slipped past the Indians to win the AL pennant. The rivalry intensified when both clubs were moved to the newly created AL Central in 1994. During that season, the two teams challenged for the division title, with the Indians one game back of Chicago when the season ended in August due to the players' strike. During a game in Chicago, the White Sox confiscated Albert Belle's corked bat, followed by an attempt by Indians pitcher Jason Grimsley to crawl through the Comiskey Park clubhouse ceiling to retrieve it. Belle later signed with the White Sox in 1997, adding additional intensity to the rivalry. In 2005, the White Sox led the division by 15 games in July, only to see the Indians trim the lead to a single game late in the season. However, the White Sox swept a three-game series to end the season to win the division by six games; the Sox later won that year's World Series.

On August 5, 2023, Cleveland third baseman José Ramírez and Chicago shortstop Tim Anderson instigated a bench-clearing brawl after Anderson applied a tag to Ramírez. Anderson then attempted to punch Ramírez, after which Ramírez wound up up knocking Anderson to the ground with a right hook. Anderson and Ramírez were suspended five and two games, respectively, for their roles in the brawl.

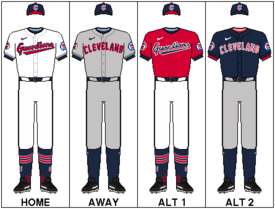

Uniforms

The official team colors are navy blue, red, and white.[140][141][142]

Home

The primary home uniform is white with red and navy blue piping around each sleeve. Across the front of the jersey in script font is the word "Guardians" in red with a navy blue outline, with navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

The alternate home jersey is red with a navy blue "diamond C" font "Guardians" trimmed in white on the front, and white and navy blue piping on both sleeves, with navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

In 2024, the team introduced "City Connect" uniforms, primarily (but not exclusively) worn on Friday home dates. The jerseys are blue with red and white stripes going down the sleeve, featuring "CLE" on the front of the jersey and the player names and numbers on the back (all in a white art deco style font), with sandstone colored pants and red socks featuring a logo which was also introduced in 2024 (a "Guardians of Traffic" statue holding a baseball bat).[143]

The standard home cap is red with a navy blue bill, and features a navy blue "diamond C" on the front and is worn with the primary white uniforms. With the alternate red jerseys, the cap is navy blue with a red bill and red "diamond C". The "City Connect" home cap is similar to the alternate cap with the exception of the front section over the bill being white.

Road

The primary road uniform is gray, with "Cleveland" in navy blue "diamond C" letters, trimmed in red across the front of the jersey, red and navy blue piping around the sleeves, and navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

The alternate road jersey is navy blue with a red "diamond C" trimmed in white on the front of the jersey, red and white piping around the sleeves, and navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

With either road jersey, the team wears a navy blue cap with a red bill and red "diamond C".

Universal

For all games, the team uses a navy blue batting helmet with a red "diamond C" on the front.[144]

All jerseys (sans the "City Connect" version) feature the "winged G" logo on one sleeve, and every jersey has a patch from Marathon Petroleum – in a sponsorship deal lasting through the 2026 season – on the other. The sleeve featuring the Marathon logo depends on how the player bats – left handed hitters have it on their right sleeve, as that is the arm facing the main TV camera when he bats, and vice versa for right handed batters.[145]

Former name and logo controversy

- Logo from 1946 to 1950

- Chief Wahoo logo used from 1949 through 2018

- "Block C" logo used secondarily from 2014 until 2019, then as the team's primary logo from 2019 through 2021 – the final three years under the Indians name

The club name and its cartoon logo have been criticized for perpetuating Native American stereotypes. In 1997 and 1998, protesters were arrested after effigies were burned. Charges were dismissed in the 1997 case, and were not filed in the 1998 case. Protesters arrested in the 1998 incident subsequently fought and lost a lawsuit alleging that their First Amendment rights had been violated.[146][147][148][149]

Bud Selig (then-Commissioner of Baseball) said in 2014 that he had never received a complaint about the logo. He has heard that there are some protesting against the mascots, but individual teams such as the Indians and Atlanta Braves, whose name was also criticized for similar reasons, should make their own decisions.[150] An organized group consisting of Native Americans, which had protested for many years, protested Chief Wahoo on Opening Day 2015, noting that this was the 100th anniversary since the team became the Indians. Owner Paul Dolan, while stating his respect for the critics, said he mainly heard from fans who wanted to keep Chief Wahoo, and had no plans to change.[151]

On January 29, 2018, Major League Baseball announced that Chief Wahoo would be removed from the Indians' uniforms as of the 2019 season, stating that the logo was no longer appropriate for on-field use.[152][153] The block "C" was promoted to the primary logo; at the time, there were no plans to change the team's name.[154]

In 2020, protests over the murder of George Floyd, a black man, by a Minneapolis police officer, led the United States into a period of social changes. This made Dolan to reconsider use of the Indians name.[155][156] On July 3, 2020, on the heels of the Washington Redskins announcing that they would "undergo a thorough review" of that team's name, the Indians announced that they would "determine the best path forward" regarding the team's name and emphasized the need to "keep improving as an organization on issues of social justice".[157]

On December 13, 2020, it was reported that the Indians name would be dropped after the 2021 season out of respect for the Native American community.[158][159] It had been hinted by the team that they may move forward without a replacement name (in a similar manner to the Washington Football Team, which used its name for 2 years until being named the Washington Commanders).[158][160] It was announced via Twitter on July 23, 2021, that the team will be named the Guardians, after the Guardians of Traffic, eight large Art Deco statues on the Hope Memorial Bridge, located close to Progressive Field.[161]

The club, however, found itself amid a trademark dispute with a men's roller derby team called the Cleveland Guardians.[162][163][164] The Cleveland Guardians roller derby team has competed in the Men's Roller Derby Association since 2016.[165] In addition, two other entities have attempted to preempt the team's use of the trademark by filing their own registrations with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.[162] The roller derby team filed a federal lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio on October 27, 2021, seeking to block the baseball team's name change.[166][167][168] On November 16, 2021, the lawsuit was resolved, and both teams were allowed to continue using the Guardians name. The name change from Indians to Guardians became official on November 19, 2021.[169][170][12][13][14][5][15]

Media

Radio

iHeart Media Cleveland sister stations WTAM (1100 AM/106.9 FM) and WMMS (100.7 FM) serve as the flagship stations for the Cleveland Guardians Radio Network,[171] with lead announcer Tom Hamilton and Jim Rosenhaus calling the games.[172]

Fellow sister station WARF (1350 AM) - while primarily an English language station - airs Spanish broadcasts of home games, complimenting the flagship coverage. Rafa Hernández-Brito serves as the primary Spanish announcer, alongside analyst and former Indian Carlos Baerga (Octavio Sequera fills in when Brito calls Cleveland Cavaliers Spanish radio broadcasts).[173]

TV

In October 2024, as a result of bankruptcy proceedings involving former broadcaster Diamond Sports Group, Major League Baseball's local media division announced that it would take over the production and distribution of Guardians games starting with the 2025 season.[174]

Prior to the 2025 season, television rights were held by Bally Sports Great Lakes. Lead announcer Matt Underwood, analyst and former Indians Gold Glove-winning centerfielder Rick Manning, and field reporter Andre Knott formed the broadcast team, with Al Pawlowski and former Indians pitcher Jensen Lewis serving as pregame and postgame hosts. Former Indians Pat Tabler and Chris Gimenez served as contributors and periodic fill-ins for Manning and Lewis.[172][175] Select games were simulcast over-the-air on WKYC channel 3.[176]

Past announcers

Notable former broadcasters include Tom Manning, Jack Graney (the first ex-baseball player to become a play-by-play announcer), Ken Coleman, Joe Castiglione, Van Patrick, Nev Chandler, Bruce Drennan, Jim "Mudcat" Grant, Rocky Colavito, Dan Coughlin, and Jim Donovan.

Previous broadcasters who have had lengthy tenures with the team include Joe Tait (15 seasons between TV and radio), Jack Corrigan (18 seasons on TV), Ford C. Frick Award winner Jimmy Dudley (19 seasons on radio), Mike Hegan (23 seasons between TV and radio), and Herb Score (34 seasons between TV and radio).[177]

Popular culture

Under the Cleveland Indians name, the team has been featured in several films, including:

- The Kid from Cleveland – a 1949 film featuring then-owner Bill Veeck and numerous players from the team (coming off winning the 1948 World Series).

- Major League – a 1989 film centered around a fictionalized version of the Indians.

- Major League II – a 1994 sequel to the 1989 original.

Awards and honors

Baseball Hall of Famers

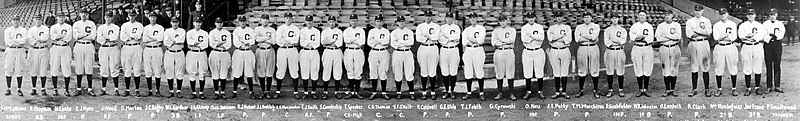

| Cleveland Guardians Hall of Famers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients

| Cleveland Guardians Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Retired numbers

|

- Jackie Robinson's number 42 is retired throughout Major League Baseball.

- The number 455 was retired in honor of the Indians fans after the team sold out 455 consecutive games between 1995 and 2001, which was an MLB record until it was surpassed by the Boston Red Sox on September 8, 2008.

Guardians Hall of Fame

Statues

Numerous Naps/Indians players have had statues made in their honor:

In and around Progressive Field

- Bob Feller (team all-time leader in wins and strikeouts by a pitcher, 1948 World Series Champion, eight-time All-Star) – since 1994*

- Jim Thome (team all-time leader in home runs and walks by a hitter, three-time All-Star with the Indians) – since 2014*

- Larry Doby (First black player in the American League, 1948 World Series Champion, seven-time All-Star) – since 2015*

- Frank Robinson (Became first black manager in MLB history when he served as player/manager from 1975 to 1977) – since 2017

- Lou Boudreau (1948 AL MVP, 1948 World Series Champion as player/manager, eight-time All-Star) – since 2017*[178]

In and around Cleveland

- Hall of Fame outfielder Elmer Flick has a statue in his hometown of Bedford, Ohio, a nearby suburb of Cleveland – since 2013*

- Former outfielder Luke Easter has a statue outside of his namesake park on the east side of Cleveland – since 1980 (when the park was renamed in Easter's honor following his murder)[179]

- Five-time All-Star (with the Indians) outfielder Rocky Colavito has a statue in Cleveland's Little Italy neighborhood – since August 10, 2021.[180][181]

(*) – Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame as an Indian/Nap.

Murals

In July 2022 - in honor of the 75th anniversary of Larry Doby becoming the AL's first black player - a mural was added to the exterior of Progressive Field, honoring players who were viewed as barrier breakers that played for the Indians/Guardians. The mural features Doby, Frank Robinson, and Satchel Paige.[182]

Streets

A portion of Eagle Avenue near Progressive Field was renamed "Larry Doby Way" in 2012[183]

Parks and fields

A number of parks and newly built and renovated youth baseball fields in Cleveland have been named after former and current Indians/Guardians players, including:

- Luke Easter Park - named for Easter in 1980 following his murder[184]

- Jim Thome All-Star Complex - 2019[185]

- CC Sabathia Field at Luke Easter Park - 2021[186]

- José Ramírez Field - 2023[187]

Franchise records

Season records

- Highest batting average: .408, Joe Jackson (1911)

- Most games: 163, Leon Wagner (1964)

- Most runs: 140, Earl Averill (1930)

- Highest slugging %: .714, Albert Belle (1994)

- Most doubles: 64, George Burns (1926)

- Most triples: 26, Joe Jackson (1912)

- Most home runs: 52, Jim Thome (2002)

- Most RBIs: 165, Manny Ramírez (1999)

- Most stolen bases: 75, Kenny Lofton (1996)

- Most wins: 31, Jim Bagby, Sr. (1920)

- Lowest ERA: 1.16, Addie Joss (1908)

- Strikeouts: 348, Bob Feller (1946)

- Complete games: 36, Bob Feller (1946)

- Saves: 47, Emmanuel Clase (2024)

- Longest win streak: 22 games (2017)

Roster

| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers

Infielders

Outfielders

|

Pitchers Catchers

Outfielders

|

Manager

Coaches

39 active, 0 inactive, 3 non-roster invitees

| |||

Minor league affiliations

The Cleveland Guardians farm system consists of seven minor league affiliates.[188]

Regular season home attendance

| Home Attendance at Jacobs/Progressive Field[189] | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | AL rank | |

| 2000 | 3,456,278 | 42,670 | 1st | |

| 2001 | 3,175,523 | 39,694 | 3rd | |

| 2002 | 2,616,940 | 32,308 | 5th | |

| 2003 | 1,730,002 | 21,358 | 12th | |

| 2004 | 1,814,401 | 22,400 | 12th | |

| 2005 | 2,013,763 | 24,861 | 12th | |

| 2006 | 1,997,995 | 24,667 | 11th | |

| 2007 | 2,275,912 | 28,449 | 9th | |

| 2008 | 2,169,760 | 26,787 | 9th | |

| 2009 | 1,766,242 | 21,805 | 13th | |

| 2010 | 1,391,644 | 17,181 | 14th | |

| 2011 | 1,840,835 | 22,726 | 9th | |

| 2012 | 1,603,596 | 19,797 | 13th | |

| 2013 | 1,572,926 | 19,419 | 14th | |

| 2014 | 1,437,393 | 17,746 | 15th | |

| 2015 | 1,388,905 | 17,361 | 14th | |

| 2016 | 1,591,667 | 19,650 | 13th | |

| 2017 | 2,048,138 | 25,286 | 11th | |

| 2018 | 1,926,701 | 23,786 | 9th | |

| 2019 | 1,738,642 | 21,465 | 9th | |

| 2020 | 0* | 0 | T-1st | |

| 2021 | 1,114,368** | 13,758 | 10th | |

| 2022 | 1,295,870 | 15,998 | 12th | |

| 2023 | 1,834,068 | 23,541 | 10th | |

(*) - There were no fans allowed in any MLB stadium in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

(**) - At the beginning of the season, there was a limit of 30% capacity due to COVID-19 restrictions implemented by Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. On June 2, DeWine lifted the restrictions, and the team immediately allowed full capacity at Progressive Field.

See also

- Cleveland Guardians all-time roster

- List of Cleveland Guardians managers

- List of Cleveland Guardians seasons

- List of Cleveland Guardians team records

- List of World Series champions

Notes

References

- ^ Nicks, Michelle (October 12, 2024). "Guardians fans react after grand slam sends the Guards to New York". WOIO. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Axisa, Mike (November 3, 2016). "Now that Cubs are champs, Indians have MLB's longest World series drought". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

So, with the Cubs finally on top, the longest championship drought in baseball now belongs to the team they beat – the Indians. Cleveland has not won a World Series since way back in 1948.

- ^ Bloch, Mark (October 27, 1997). "Cleveland's Legacy of Loss". ESPN.com. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ "Iconic Cleveland: The History Behind Cleveland's Guardians of Traffic". clevelandmagazine.com. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Bell, Mandy (July 23, 2021). "New for '22: Meet the Cleveland Guardians". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Cleveland MLB team officially changes name to 'Guardians'". SportsNet. July 23, 2021. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "Slider: Guardians Mascot". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Goodyear Ballpark". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Adler, David; Kelly, Matt (October 23, 2016). "History lesson: 20 amazing Cubs and Indians facts". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Bell, Mandy (December 21, 2020). "History of Cleveland's baseball team name". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Timeline". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Bell, Mandy (November 17, 2021). "Cleveland set for 'Guardians' name transition". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Cleveland Indians announce decision to change current team name". CLEGuardians.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. December 14, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Waldstein, David; Schmidt, Michael S. (December 13, 2020). "Cleveland's Baseball Team Will Drop Its Indians Team Name". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hoynes, Paul (July 23, 2021). "Cleveland Indians choose Guardians as new team name". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Cleveland Guardians Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Harold 1960: 4

- ^ "The First Professional Baseball Team Was the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings". Today I Found Out. April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Martin, Michael A. (2001). Ohio, the Buckeye State. Gareth Stevens. ISBN 9780836851243. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "The 1872 Cleveland Forest Citys". retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 9. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ "The 1899 Cleveland Spiders". David Fleitz. wcnet.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ Hittner, Arthur (2003). Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball's Flying Dutchman. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1811-7.

- ^ "Bob Diskin, Special to ESPN.com, A pitcher worthy of a trophy". Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Project Ballpark". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ Castrovince, Anthony (July 23, 2021). "What's in a name? Introducing the Guardians". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

The AL outfit originated as a Western League team known as the Grand Rapids Rustlers, then the Cleveland Lakeshores.

- ^ 2023 Cleveland Guardians Media Guide. Cleveland Guardians. p. 2. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 11. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Posnanski, Joe (October 14, 2016). "What's in a name?". NBC SportsWorld. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. pp. 12–13. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Seymour, Harold (1960). Baseball. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0-19-500100-1.

- ^ "1908 American League Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 319. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 413. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ "Obituary, Pitcher Joss Dead: Ill Only Few Days" (PDF). The New York Times. April 15, 1911. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "1914 American League Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ "1915 American League Standings". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 321. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ "Baseball writers select 'Indians' as the best name to apply to the former Naps" The Plain Dealer January 17, 1915: 15

- ^ "Looking Backwards" The Plain Dealer January 18, 1915: 8

- ^ a b Lewis, Franklin (2006). The Cleveland Indians. Kent State University Press reprint from Putnam. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-87338-885-6.

- ^ Ratajczak, Kenneth (2008). The Wrong Man Out. AuthorHouse. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-4343-5678-9.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken (1996). Baseball: An Illustrated History. Knopf. p. 153. ISBN 0-679-76541-7.

- ^ "Report of Chapman's Death". The New York Times. August 1, 1920. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Standings – Monday, Aug 16, 1920". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (October 13, 1989). "SPORTS OF THE TIMES; When Sewell Replaced Ray Chapman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ "CLE 1920 Cleveland Indians Schedule". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ "1920 Chicago White Sox Schedule". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, Bruce (March 11, 1985). "When Baseballs Fell from On High, Henry Helf Rose to the Occasion". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ C. Phillip Francis. "The Cleveland Crybabies". Chatter from the Dugout. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ DeMaio Brewer, Lisa (June 21, 2000). "A National Treasure Calls Wilkes "Home"". The Record of Wilkes, N.C. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Housh, Leighton (April 4, 1965). "Hal Trosky, Norway, 1965". Des Moines Register. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 52. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Schneider, Russell (2001). Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. pp. 56, 346. ISBN 1-58261-376-1.

- ^ Boxerman, Burton Alan; Boxerman, Benita W. (2003). Ebbets to Veeck to Busch: Eight Owners Who Shaped Baseball. McFarland. p. 128. ISBN 0-7864-1562-2. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ "Baseball's Clown Prince Dies". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Borsvold, David (2003). The Cleveland Indians: Cleveland Press Years, 1920–1982. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-7385-2325-9. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Lowry, Phillip (2005). Green Cathedrals. New York City: Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1562-1.

- ^ Briggs, David (August 8, 2007). "League Park may glisten once again". CLEGuardians.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Satchel Paige 1948 Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "The Kid from Cleveland". IMDB.com. September 5, 1949. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ Ribowsky, Mark (2000). Don't Look Back: Satchel Paige in the Shadows of Baseball. Da Capo Press. p. 286. ISBN 0-306-80963-X.[permanent dead link]