Clement of Metz

Saint Clement of Metz | |

|---|---|

Saint Clement, first bishop of Metz, near ruins of the amphitheater. By Auguste Migette (ca. 1850). | |

| Bishop | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast | 23 November |

Clement of Metz (Latin: Clemens de Metiae; French: Clément de Metz) is venerated as the first Bishop of Metz. According to tradition, he was sent by Peter to Metz during the 1st century, with two disciples: Celestius (Céleste de Metz) and Felix (Felix de Metz), who are listed as his successors in that see. However, this legend may have been constructed much later to lend more antiquity to the episcopal see, and to make the diocese of Metz appear to be more ancient than it actually was.[1] As Hippolyte Delehaye writes, "To have lived amongst the Saviour's immediate following was...honorable...and accordingly old patrons of churches were identified with certain persons in the gospels or who were supposed to have had some part of Christ's life on earth."[2] Elaboration of this legend states that Clement was the uncle of Pope Clement I.[3][4]

Clement may have actually arrived at Metz at the end of the 3rd century,[1] though the first fully authenticated bishop, however, is Sperus or Hesperus, who was bishop in 535.[5]

Legend of the Graoully dragon

Clement of Metz, like many other saints,[note 1] is the hero of a legend in which he is the vanquisher of a local dragon. In the legend of Clement it is called the Graoully or Graouilly.[1] The legend states that the Graoully, along with countless other snakes, inhabited the local Roman amphitheater. The snakes' breath had so poisoned the area that the inhabitants of the town were effectively trapped in the town. After converting the local inhabitants to Christianity after they agreed to do so in return for ridding them of the dragon, Clement went into the amphitheater and quickly made the sign of the cross after the snakes attacked him. They immediately were tamed by this. Clement led the Graoully to the edge of the Seille, and ordered him to disappear into a place where there were no men or beasts. Orius did not convert to Christianity after Clement tamed the dragon. However, when the king's daughter died, Clement brought her back from the dead, thereby resulting in the king's conversion.[1]

The Graoully quickly became a symbol of the town of Metz, and can be seen in numerous demonstrations of the city, since the 10th century. In the Middle Ages, a large effigy of the Graoully was carried during processions in the town. The Graoully was a large canvas figure stuffed with hay and twelve feet high.[1] The French Renaissance writer François Rabelais described the Graoully's effigy during a procession of the 16th century:

It was a monstrous, hideous effigy, terrifying for small children, with eyes bigger than the stomach, and a head bigger than the rest of the body, with horrific, wide jaws and many teeth which were made to clash by the use of a cord, making terrible noises as if the dragon of Saint Clement was actually in Metz.

— François Rabelais, The Fourth Book

During the 18th century, bakers gave the dragon a small loaf of white bread, while on the last day of Rogation days, children whipped the effigy in the courtyard of the abbey of Saint Arnould, which was the last stage of the procession.[1] Poet Paul Verlaine was also frightened as a child by the "cardboard monster" during the processions in his hometown. Authors from Metz tend to present the legend of the Graoully as a symbol of Christianity's victory over paganism, represented by the harmful dragon. Today, the Graoully remains one of the major symbols of Metz. A representation of the Graoully from the 16th century may be seen in the crypt in the cathedral. Also, a semi-permanent sculpture of the Graoully is suspended in mid-air on Taison street, near the cathedral. Moreover, the Graoully is shown on the heraldic emblems of Metz's football club and it is also the nickname of Metz's ice hockey team.

Violist and composer Alain Celo, from the National Orchestra of Lorraine, has written a piece for ensemble entitled The Graoully, Messin dragon. The piece is a musical story with narration depicting the epic fight between Clement and the legendary dragon in the Roman amphitheater.

- Seal of the Saint Clement abbey during the 14th century

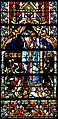

- Clément de Metz, Window by Hermann de Munster, 14th century, Cathedral of Metz

Legend of the stag

Another legend associated with Clement states that a stag took refuge under his knees on two occasions, thereby convincing the local king, Orius, whose dogs were in pursuit of the stag, of Clement's sanctity.[1]

Veneration

The celebration of Saint Clement of Metz is 23 November. Also, the major abbey in Metz, now home to the Lorraine parliament, was named after him.

Notes

- ^ In Italy, Saint Mercurialis, first bishop of the city of Forlì, is also depicted slaying a dragon; Saint Julian of Le Mans, Saint Veran, Saint Bienheuré, Saint Crescentinus, Saint Margaret of Antioch, Saint Martha, Saint Quirinus of Malmedy, and Saint Leonard of Noblac were also venerated as dragon-slayers.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g The Graoully, symbol of Metz Archived 2011-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hippolyte Delehaye, The Legends of the Saints (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 1955), 37.

- ^ Bibliothèque sacrée, ou Dictionnaire universel historique, dogmatique, canonique, géographique et chronologique des sciences ecclésiastiques p418 Charles-Louis Richard 1827

- ^ Histoire de la ville et du pays de Gorze p24 Par Jean Baptiste Nimsgern 1853

- ^ Wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Metz