Early Modern Irish

| Early Modern Irish | |

|---|---|

| Early Modern Gaelic | |

| Gaoidhealg | |

| |

| Native to | Scotland, Ireland |

| Era | c. 1200 to c. 1600 |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ghc |

ghc.html | |

| Glottolog | hibe1235 |

Early Modern Irish (Irish: Gaeilge Chlasaiceach, lit. 'Classical Irish') represented a transition between Middle Irish and Modern Irish.[1] Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.[2][3]

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish (Gaoidhealg) was a shared literary form of Gaelic that was in use by poets in Scotland and Ireland from the 13th century to the 18th century.

Although the first written signs of Scottish Gaelic having diverged from Irish appear as far back as the 12th century annotations of the Book of Deer, Scottish Gaelic did not have a separate standardised form and did not appear in print on a significant scale until the 1767 translation of the New Testament into Scottish Gaelic;[4] however, in the 16th century, John Carswell's Foirm na n-Urrnuidheadh, an adaptation of John Knox's Book of Common Order, was the first book printed in either Scottish or Irish Gaelic.[5]

Before that time, the vernacular dialects of Ireland and Scotland were considered to belong to a single language, and in the late 12th century a highly formalized standard variant of that language was created for the use in bardic poetry. The standard was created by medieval Gaelic poets based on the vernacular usage of the late 12th century and allowed a lot of dialectal forms that existed at that point in time,[6] but was kept conservative and had been taught virtually unchanged throughout later centuries. The grammar and metrical rules were described in a series of grammatical tracts and linguistic poems used for teaching in bardic schools.[7][8]

External history

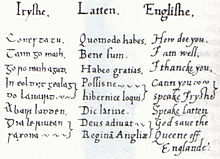

The Tudor dynasty sought to subdue its Irish citizens. The Tudor rulers attempted to do this by restricting the use of the Irish language while simultaneously promoting the use of the English language. English expansion in Ireland, outside of the Pale, was attempted under Mary I, but ended with poor results.[9] Queen Elizabeth I was proficient in several languages and is reported to have expressed a desire to understand Irish.[10] A primer was prepared on her behalf by Christopher Nugent, 6th Baron Delvin.[11]

Grammar

The grammar of Early Modern Irish is laid out in a series of grammatical tracts written by native speakers and intended to teach the most cultivated form of the language to student bards, lawyers, doctors, administrators, monks, and so on in Ireland and Scotland. The tracts were edited and published by Osborn Bergin as a supplement to Ériu between 1916 and 1955 under the title Irish Grammatical Tracts.[12] and some with commentary and translation by Lambert McKenna in 1944 as Bardic Syntactical Tracts.[13][7]

The neuter gender is gone (formerly neuter nouns transition mostly to masculine, occasionally feminine categories) – but some historically neuter nouns may still optionally cause eclipsis of a following complement (eg. lá n-aon "one day"), as they did in Old Irish. The distinction between preposition + accusative to show motion toward a goal (e.g. san gcath "into the battle") and preposition + dative to show non–goal-oriented location (e.g. san chath "in the battle") is lost during this period in the spoken language, as is the distinction between nominative and accusative case in nouns, but they are kept in Classical Gaelic. The Classical Gaelic standard also requires the use of accusative for direct object of the verb if it is different in form from the nominative.

Verb endings are also in transition.[1] The ending -ann (which spread from conjunct forms of Old Irish n-stem verbs like benaid, ·ben "(he) hits, strikes"), today the usual 3rd person ending in the present tense, was originally just an alternative ending found only in verbs in dependent position, i.e. after particles such as the negative, but it started to appear in independent forms in 15th century prose and was common by 17th century. Thus Classical Gaelic originally had molaidh "[he] praises" versus ní mhol or ní mholann "[he] does not praise", whereas later Early Modern and Modern Irish have molann sé and ní mholann sé.[3] This innovation was not followed in Scottish Gaelic, where the ending -ann has never spread,[14][15] but the present and future tenses were merged: glacaidh e "he will grasp" but cha ghlac e "he will not grasp".[16]

The fully stressed personal pronouns (which developed during Middle Irish out of Old Irish pronouns that were reserved for copular predicatives) are allowed in object and optionally in subject positions. If the subject is a 1st or 2nd person pronoun stated explicitly, the 3rd person form of the verb is used – most verb forms can take either the synthetic or analytic form, for example "I will speak" can be expressed as laibheórad (1st sg. form) or laibheóraidh mé (3rd sg. form and 1st sg. pronoun mé). The singular form is also used with 1st and 2nd person plural pronouns (laibheóraidh sinn "we will speak", laibheóraidh sibh "ye will speak") but the 3rd person plural form is used whenever a 3rd person plural subject is expressed (laibheóraid na fir "the men will speak").

With regards to the pronouns Classical Gaelic (as well as Middle Irish) shows signs of split ergativity – the pronouns are divided into two sets with partial ergative-absolutive alignment. The forms used for direct object of transitive verbs (the "object" pronouns) are also used:

- as subjects of passive verbs, eg. cuirthear ar an mbord é "it is put onto the table" – in Modern Irish these are understood as active autonomous verbs instead,

- for subjects of the copula, eg. mo theanga, is é m'arm-sa í "my tongue, it is my weapon" (feminine í "it, she" refers back to mo theanga) – this is continued in Modern Irish,

- and they might be optionally used as subjects of intransitive verbs (instead of the "subject" pronouns) – this usage seems to indicate lack of agency or will in the subject, eg. do bhí an baile gan bheannach / go raibhe í ag Éireannach "the settlement was without a blessing until it was in the hands of an Irishman".[17]

The 3rd usage above disappeared in Modern Irish and even in Classical Gaelic the unmarked and more common pattern is to use the "subject" pronouns like with transitive verbs.

The 3rd person subject pronouns are always optional and often dropped in poetry. The infix pronouns inherited from Old Irish are still optionally used in poetry for direct objects, but their use was likely outdated in speech already in the beginning of the Early Modern period.

Literature

The first book printed in any Goidelic language was published in 1567 in Edinburgh, a translation of John Knox's 'Liturgy' by Séon Carsuel, Bishop of the Isles. He used a slightly modified form of the Classical Gaelic and also used the Roman script. In 1571, the first book in Irish to be printed in Ireland was a Protestant 'catechism', containing a guide to spelling and sounds in Irish.[18] It was written by John Kearney, treasurer of St. Patrick's Cathedral. The type used was adapted to what has become known as the Irish script. This was published in 1602-3 by the printer Francke. The Church of Ireland (a member of the Anglican communion) undertook the first publication of Scripture in Irish. The first Irish translation of the New Testament was begun by Nicholas Walsh, Bishop of Ossory, who worked on it until his murder in 1585. The work was continued by John Kearny, his assistant, and Dr. Nehemiah Donellan, Archbishop of Tuam, and it was finally completed by William Daniel (Uilliam Ó Domhnaill), Archbishop of Tuam in succession to Donellan. Their work was printed in 1602. The work of translating the Old Testament was undertaken by William Bedel (1571–1642), Bishop of Kilmore, who completed his translation within the reign of Charles the First, however it was not published until 1680, in a revised version by Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713), Archbishop of Dublin. William Bedell had undertaken a translation of the Book of Common Prayer in 1606. An Irish translation of the revised prayer book of 1662 was effected by John Richardson (1664–1747) and published in 1712.

Encoding

ISO 639-3 gives the name "Hiberno-Scottish Gaelic" (and the code ghc) to cover Classical Gaelic. The code was introduced in the 15th edition of Ethnologue, with the language being described as "[a]rchaic literary language based on 12th century Irish, formerly used by professional classes in Ireland until the 17th century and Scotland until the 18th century."[19]

See also

References

- ^ a b Bergin, Osborn (1930). "Language". Stories from Keating's History of Ireland (3rd ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

- ^ Mac Eoin, Gearóid (1993). "Irish". In Ball, Martin J. (ed.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 101–44. ISBN 978-0-415-01035-1.

- ^ a b McManus, Damian (1994). "An Nua-Ghaeilge Chlasaiceach". In K. McCone; D. McManus; C. Ó Háinle; N. Williams; L. Breatnach (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge: in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp. 335–445. ISBN 978-0-901519-90-0.

- ^ Thomson (ed.), The Companion to Gaelic Scotland

- ^ Meek, "Scots-Gaelic Scribes", pp. 263–4; Wormald, Court, Kirk and Community, p. 63.

- ^ Brian Ó Cuív (1973). The linguistic training of the mediaeval Irish poet. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-0901282-699.

But what was achieved in the second half of the twelfth century was something completely radical: the formal adoption of vernacular speech as the basis for a new literary standard. (...) If what they observed of the language at that time had been written down and identified according to regions, and if the manuscripts containing their observations had survived the vicissitudes of the intervening centuries, we would have to-day a fascinating and unique collection of descriptive linguistic material. However, what the poets did was to co-ordinate this material to produce a prescriptive grammar.

- ^ a b Brian Ó Cuív (1973). The linguistic training of the mediaeval Irish poet. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-0901282-699.

- ^ Eoin Mac Cárthaigh (2014). The Art of Bardic Poetry: A new Edition of Irish Grammatical Tracts I. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-1-85500-226-5.

- ^ Hindley, Reg. 1990. The Death of the Irish language: A qualified obituary London: Routledge, p. 6.

- ^ "Elizabeth I and languages". European Studies Blog. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "Sir Christopher Nugent, 5th Baron Delvin (1544-1602) - Facsimile of the Irish language primer commissioned for Elizabeth I". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Baumgarten, Rolf; Ó Maolalaigh, Roibeard (2004). "Electronic Bibliography of Irish Linguistics and Literature 1942–71, Irish grammatical tracts". Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Baumgarten, Rolf; Ó Maolalaigh, Roibeard (2004). "Electronic Bibliography of Irish Linguistics and Literature 1942–71, Bardic Syntactical Tracts". Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ This verbal ending -ann exists in a single phrase of Scottish Gaelic, nach maireann "deceased" (lit. "who does not live"), which is likely borrowed from the classical standard. The form maireann is understood as an adjective "alive" and not as a verbal form by modern speakers, see "maireann". Am Faclair Beag. Michael Bauer and Will Robertson. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Seosamh Watson (1994). "Gaeilge na hAlban, §19.3". In McCone, K.; McManus, D.; Ó Háinle, C.; Williams, N.; Breatnach, L. (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge: in ómós do P[h]ádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Roinn na Sean-Ghaeilge, Coláiste Phádraig. p. 688. ISBN 0-901519-90-1.

Níor tháinig an foirceann -(e)ann chun cinn in Albain, agus diomaite den fhoirm maireann a thuigtear mar aidiacht anois in abairtí de chineál nach maireann ní heol dúinn a leithéid a bheith sa teanga labhartha ann: go deimhin, tuairimíonn [J. Gleasure] gur seift a bhí i bhforás fhoirmeacha cónasctha -(e)ann an láith. i nGaeilge na hÉireann leis an idirdhealú ar an fháistineach a neartú.

[The ending -(e)ann hasn't appeared in Scotland, and apart from the form maireann which is understood as an adjective now in utterances of the type nach maireann we are not aware of its likes existing in the spoken language: indeed, [J. Gleasure] opines that the system of the present conjunct ending -(e)ann in Irish was a device to strengthen the distinction from the future tense.] - ^ Calder, George (1923). A Gaelic Grammar. Glasgow: MacLaren & Sons. p. 223.

- ^ Mícheál Hoyne (2020). "Unaccusativity and the subject pronoun in Middle and Early Modern Irish". Celtica. 32. ISSN 0069-1399.

- ^ T. W. Moody; F. X. Martin; F. J. Byrne (12 March 2009). "The Irish Language in the Early Modern Period". A New History of Ireland, Volume III: Early Modern Ireland 1534–1691. Oxford University Press. p. 511. ISBN 9780199562527. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Gaelic, Hiberno-Scottish at Ethnologue (15th ed., 2005)

Further reading

- Eleanor Knott (2011) [1928]. Irish Syllabic Poetry 1200–1600. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-1-85500-048-3.

- Osborn Bergin (2003) [1970]. "Bardic Poetry: A Lecture delivered before the National Literary Society, Dublin, 15th April, 1912". Irish Bardic Poetry: Texts and Translations. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-12-X.

- Katharine Simms; Mícheál Hoyne. "Bardic Poetry Database". Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- Brian Ó Cuív (1973). The linguistic training of the mediaeval Irish poet. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-0901282-699.

- Eoin Mac Cárthaigh (2014). The Art of Bardic Poetry: A new Edition of Irish Grammatical Tracts I. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-1-85500-226-5.

- Lambert McKenna (1979) [1944]. Bardic Syntactical Tracts. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Meek, Donald E. (1996). "The Scots-Gaelic Scribes of Late Medieval Perthshire: An Overview of the Orthography and Contents of the Book of the Dean of Lismore". In Janet Hadley Williams (ed.). Stewart Style, 1513–1542: Essays on the Court of James V. East Linton. pp. 254–72.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thomson, D., ed. (1994). The Companion to Gaelic Scotland. Gairm. ISBN 1-871901-31-6.

- Wormald, Jenny (1981). Court, Kirk and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625. Edinburgh. ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Léamh – Learn Early Modern Irish". Retrieved 11 January 2022.