Chun Afong

Chun Afong | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

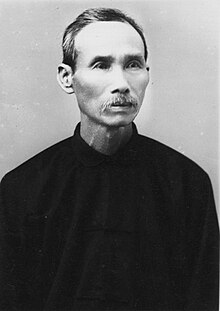

Chun Afong, c. 1882 | |||||||||||||

| Member of the Hawaiian Kingdom Privy Council of State | |||||||||||||

| In office June 5, 1879 – c. November 1879 | |||||||||||||

| Monarch | Kalākaua | ||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born | c. 1825 Meixi Village, Qianshan Town, Xiangshan County, Guangdong | ||||||||||||

| Died | September 25, 1906 (aged 80–81) Meixi Village | ||||||||||||

| Resting place | Meixi Village | ||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Lee Hong Julia Fayerweather Afong Lam May Chin (concubine) | ||||||||||||

| Children | 20 | ||||||||||||

| Occupation | Businessman | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陳芳 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 陈芳 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Chun Afong (Chinese: 陳芳; pinyin: Chén Fāng; c. 1825 – September 25, 1906) was a Chinese businessman and philanthropist who settled in the Hawaiian Kingdom during the 19th century and built a business empire in Hawaii, Macau and Hong Kong. He immigrated to Hawaii from Guangdong in 1849 and adopted the surname Afong after the diminutive form of his Cantonese given name, Ah Fong.

Afong started off working for his uncle's retail store in Honolulu and later became the co-owner of a chain of stores selling Oriental novelties. In due time, he made a fortune investing in retail, shipping, opium, sugar and coffee plantations, eventually becoming the first Chinese millionaire on Hawaii. In 1856, Afong helped organize a ball in honor of the wedding of King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma that helped to solidify the Chinese community's position in Honolulu. He briefly served as the commercial agent and diplomatic consul to the Hawaiian Kingdom and was a member of King Kalākaua's Privy Council.

While retaining a separate family in China, Afong married Hawaiian-British noblewoman Julia Fayerweather Afong, a marriage which brought with it closer ties to the Hawaiian nobility and ruling class. They raised a large mixed-race family which included many daughters and two sons: Chun Chik-yu and Chun Lung (his eldest son from his Chinese wife), who assisted him with his business empires. After four decades in Hawaii, Afong retired to his home village in 1890 leaving Julia and most of her children behind. He relocated his business empire to Macau and Hong Kong. In his last years, his charitable deeds were recognize at his hometown where the Meixi Memorial Archways was erected. He died in his home village in 1906. His life has been caricatured in 1912 short-story Chun Ah Chun, by American novelist Jack London and 13 Daughters, a short-lived 1961 Broadway musical written by his great-grandson. In 1997, Bob Dye, who married one of Afong's descendants, wrote a book chronicling his life titled Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains: Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi.

Biography

Afong was born in the village of Wong Mau Cha (黃茅斜村), Xiangshan County, the present day Meixi Village, Qianshan, Zhuhai, Guangdong.[1][note 1] He was of the Chinese Cantonese community which held a longstanding dispute with the Hakka peoples; the latter conflict spilled into the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars from 1855 to 1868.[4] Competition between Hakka and Punti continued in the immigrant communities of Hawaii.[5]

Afong arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in 1849 with his uncle to assist at his retail store in Honolulu. At the time, Hawaii was known by the Chinese as the "Sandalwood Mountains" (檀香山) after the abundant sandalwood trees which were exported to Asia during the reign of Kamehameha I.[6] When asked his name by a Hawaiian immigration official, he responded by giving his Chinese family name Chun followed by Ah Fong using the common Cantonese diminutive prefix Ah (阿). However, the official thought he had given his name in the Western fashion and thus he became Chun Afong with his Chinese given name used as his surname.[7][8]

He started his own business with his friend Qing Ming Qwai or Achuck in 1865. They became the co-owners of Afong & Achuck, a chain of stores selling Oriental novelties including brocades and silks to Chinese residents and the upper echelon of Honolulu society.[9][10][11] In 1856, Afong and the Cantonese merchant community hosted a ball in honor of the wedding of King Kamehameha IV and Emma Rooke. The multi-racial event helped to solidify the Chinese community's position in Honolulu.[12]

Afong returned to China in 1850 to marry Lee Hong (李杏), who became his primary kit-fat (wife) (结发妻).[13] However, he would marry again in Hawaii while Lee Hong remained in China. In 1857, he was naturalized as a Hawaiian subject in order to marry the British-Hawaiian noblewoman Julia Fayerweather Afong. The union connected him to the ruling Hawaiian elite class including the future king, Kalākaua, who owed his 1874 election as monarch in part to Afong's financial support. His business in Hawaii grew steadily with investments in retail, shipping, opium sales, and sugar and coffee plantations.[14] Afong soon became the first Chinese millionaire in the Hawaiian Islands.[2]

Political appointments

King Kalākaua appointed Afong to the Privy Council of State, the advisory council to the monarch, on June 5, 1879.[15][16] However, he resigned shortly afterward to become a diplomatic agent for the Chinese government in Hawaii.[17][18]

He was appointed commercial agent (shangdong) for China by the Chinese Minister to the United States in Washington, DC, Chen Lanbin, on August 13, 1879.[19] He was not recognized by the Hawaiian government until mid-February 1880 when he was issued an exequatur.[17][19] He resigned as consul in March 1882.[20]

Ultimately, the Aki opium scandal (in which his son Chun Lung, called Alung, was involved) became one of the corruption charges leading to the July 1887 coup of the king by his opponents. He was forced to sign the 1887 Bayonet Constitution which restricted his executive power.[21][22] After the signing of the Bayonet Constitution, the suffrage system in the kingdom was changed. New racial and property restrictions targeting poor Native Hawaiians and all Asians were implemented. These groups, along with many naturalized subjects of Chinese descent who had been able to vote in previous elections, were disenfranchised, while the vote was extended to non-naturalized foreign Euro-American residents.[23][24]

Return to China

After his eldest son Alung died in August 1889, he sold or reorganized most of his business holdings in Hawaii and invested in the Douglas Steamship Company in Hong Kong. He named Samuel Mills Damon as administrator of an estate left in Hawaii to support his wife Julia and their many children.[9] He relocated his business quarter to Hong Kong and Macau and sailed from Hawaii for a final time on October 17, 1890. Toney (Chun Chik-yu), his eldest son by Julia, accompanied him back to assist him and would later become an influential businessman in his own right. Afong would remain in China for the rest of his life while managing his remaining business abroad.[25]

On September 25, 1906, Afong died quietly at the age of 81 at his home in Meixi Village.[26][27]

Legacy

Former residences and memorials

In his hometown, the Meixi Memorial Archways, combining Chinese and European architectural elements, were built by order in 1886 and 1891 to commemorate the charitable deeds of Chun Afong and his father in their home village. He was also made a mandarin of the first rank by imperial edict and was awarded with four tablets bearing the words: "Generous, Charitable, Selfless and Kindhearted". The property, part of the larger Chun family estate, includes the family mansion, gardens, ancestral temple, and the cemetery grounds of the extended family. The site was looted and vandalized during the Cultural Revolution and one of the four arches was destroyed. Even Afong's grand tomb was ransacked and his remains later reburied in a more simple grave next to his first wife, his concubine and son Toney. The residence was subsequently used as barracks and later dormitories for factory workers. The Chun family estate in Meixi is presently a museum and tourist attraction.[1][28][29]

The first lychee (litchi chinensi) tree in Hawaii was planted at Afong's Honolulu mansion on Nuʻuanu Avenue and School Street in 1873 by his business associate and friend Achuck, who had brought the plant back from a trip to China. The tree later became known as the "Afong" tree. The cultivar variety once identified as Guiwei was later re-identified as the Dazou variety.[30][31][32] The lychee tree still stands at the former Nuʻuanu Shopping Plaza (now a Walgreens) along with a banyan tree (reportedly the oldest banyan in Honolulu) also planted by Afong. A second historic banyan tree was cut down in 2005.[33][34]

The site of Afong's Waikiki villa, where he entertained royalty and dignitaries, was sold in 1904 to the United States Army Corps of Engineers for the construction of Battery Randolph and Battery Dudley, built to defend Honolulu Harbor from foreign attacks. It is now part of the property of the U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii and Fort DeRussy Military Reservation. There is an informational marker describing the villa and Afong's legacy and it is a stop on the Waikīkī Historic Trail.[34][35]

Literary representation

In 1909, Chun Afong's life was fictionalized in the short magazine story, "Chun Ah Chun", by American novelist Jack London. It was later published in his 1912 book The House of Pride: And Other Tales of Hawaii. London's highly embellished story of Afong depicts him as a "crafty coolie" who spites the white capitalist establishment through his own business success. He also entices white men with money to marry his racially-mixed daughters across the color-line.[36] In 1961, his great-grandson Eaton "Bob" Magoon Jr. wrote the book, music and lyrics to 13 Daughters, a short-lived Broadway musical. Don Ameche played the eponymous Chun.[9][36][37]

In 1997, Kailua-based freelance writer and historian Bob Dye (1928–2010) wrote Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains: Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi. The book was dedicated to his wife ballet dancer Tessa Gay Magoon Dye (1946–2002), a great-great-granddaughter of Chun Afong, who assisted her husband with her personal research into her family history. The couple visited the site of Afong's old family compound in Meixi and were consulted by the local Chinese authorities when they were transforming it into a museum and tourist attraction. Dye's book was praised for its meticulous research and detailed account of the experiences Afong and of the Chinese immigrant community in Hawaii.[38][39][40][41] In a 1998 review in Hawaiian Historical Society's The Hawaiian Journal of History, contributing professor Loretta Pang noted:

Bob Dye has enriched our understanding of the complexities of life in Hawaiʻi. This labor of familial love (his wife, to whom the book is dedicated, is Afong's great-great granddaughter) pares away some of the myth surrounding Chun Afong and the immigrant experience. In a way, what emerges is a cautionary tale of the dangers of a single-crop economy and weak political leadership, the human cost of diplomatic maneuvers, and the difficulties of creating a multicultural society free from exploitation. Yet although the title of the book refers to Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi, the two dimensions alluded to are not explored as fully as they might be. That is, Afong's relations with and place among the Chinese in Hawaiʻi and the place of the Chinese among the native people of Hawaiʻi with whom Afong associated are topics deserving fuller treatment in their own right and as approaches to understanding Afong.[42]

Marriage and children

Chun Afong fathered a large family with his two wives Lee Hong (who remained in Meixi) and Julia Fayerweather Afong (who remained in Hawaii) and one concubine (also in China). The following list of descendants is compiled from the family history of his descendants in Dye's Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains:[43]

With his primary wife Lee Hong (李杏), he had three sons:[44]

- Chan Lung, known as Chun Lung or Alung, (1852–1889), married Ung See Soy and had three children: Chan Mui-Ngan, Chan Wing-On and Chan Unnamed. He graduated from Yale University and co-partnered with his father in his business in Hawaii.[45]

- Chan Kang-Yu (1863–1924), had no children.[46]

- Unnamed

With his second wife Julia Fayerweather Afong, he had sixteen children:[47][48][49]

- Emmeline Agatha Marie Kailimoku Afong (1858–1946), married firstly Henry Giles and had one daughter; and married secondly John Alfred Magoon and had seven children.[50]

- Antone "Toney" Abram Kekapala Keawemauhili Afong / Chun Chik-yu (1859–1936), married Chang Julien and had three children: Chun Wing-Sen, Irene Chun Wing-Luen, Chun Wing-Keu. He served as governor of Guangdong from 1922 to 1923.[51]

- Nancy Eldorah Luhana Frederica Afong (1861–1940), married Francis Blately McStocker and had three children. Her husband served as chairman of the executive committee of the Annexation Club and helped form the Citizens' Guard, the armed militia of the Republic of Hawaii.[52]

- Mary Catherine Afong (1862–1945), never married.[53]

- Julia Hope Afong (1864–1953), married Arthur Miller Johnstone and had eight children.[54]

- Marie Kekulani Afong (1867–1925), married Abram Stephanus Humphreys and had four children.[55]

- Elizabeth K. Afong (1869–1965), married Ignatius R. Burns and had no children.[56]

- Henrietta (Etta) Patrinella Kealaiki Afong (1870–1940), married firstly United States Navy Rear Admiral William Henry Whiting and had a daughter; and married secondly Rear Admiral Ammen Farenholt and had no children.[57]

- Alice Lillian Afong (1872–1953), married Edson Lewis Hutchinson and had one son.[58]

- Helen Gertrude Afong (1873–1953), married firstly William A. Henshall and had one son; and married secondly her husband's brother George F. Henshall and had no children.[59]

- Caroline Bartlett Afong (1874–1942), married first Jacob Morton Riggs; and married secondly Leonard Camp. No children from both marriages.[60]

- James Edward Fayerweather Afong (1875–1875), died young, known as Jimmie.[61]

- Albert Fayerweather Leialoha Afong (1877–1948), married Anna Elizabeth Whiting and had four children: Elizabeth Kamakia Afong, Mary Katherine Afong, Katherine Whiting Afong, and Julia Fayerweather Afong. He became the first person of Chinese descent to head the Honolulu Stock Exchange.[62]

- Martha Muriel Afong (1878–1983), married Andrew J. Dougherty and had three children.[53]

- Beatrice Melanie Afong (1880–1959), married firstly James Walter Wall Brewster and had two children; and married secondly Frank Moss and had no children.[63]

- Abram Henry Afong (1883–1933), married May Harvey and had one son Alvin Henry Afong.[64]

With his concubine Lam May Chin, he had a son:

- Chan Ying Siu, born c. 1870s in China.[65]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b Dye 1997, pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b Ng 1999, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Lin 1991, p. 321.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 31.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 6, 10–11.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Ng 1999, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Day 1984, p. 1.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 97.

- ^ Dye 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Dye 1994, pp. 70–78.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 27–35.

- ^ Dye 2010, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Hawaii state office record

- ^ Hawaii Privy Council 1875–81

- ^ a b Kuykendall 1967, p. 139.

- ^ Kauanui & Kauanui 2008, p. 136–138.

- ^ a b Dye 2010, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 185.

- ^ Lim-Chong & Ball 2010, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Alexander 1896, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Chou 2010, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 366–372.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 217–230.

- ^ Dye 2010, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 229.

- ^ Liang 2012.

- ^ Travel China Guide.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 110.

- ^ Higgins 1917, p. 5.

- ^ Zee et al. 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Hoover 2009; Gomes 2010; Gonser 2005

- ^ a b Sigall 2013a; Sigall 2013b; Sigall 2015

- ^ The Historical Marker Database 2008

- ^ a b Dye 1997, pp. 3, 231–233.

- ^ Dye 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. v.

- ^ Tsai 2010.

- ^ Gee 2002.

- ^ Creamer 2002.

- ^ Pang 1998, pp. 210–215.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. front, 223–230.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 33–35, 52, 60, 63, 69, 70, 192, 223, 229.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 52, 80, 89, 91, 92, 107, 108, 121–123, 125, 126, 134, 135, 138, 144, 149, 175, 178, 183, 184, 193, 194, 207–209, 211, 213–215, 220.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 194, 229–230.

- ^ Day 1987, p. 154.

- ^ Lam 1932, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 63–75, 111, 191.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 68, 142–144, 155, 189, 211, 221.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 2, 4, 70, 78–80, 92, 126, 178, 192–194, 216, 223, 229–230.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 81, 142, 194–195, 225, 227.

- ^ a b Dye 1997, p. front.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 195–196, 216.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 81, 157, 193, 228.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 92, 161, 164.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 98, 124, 225–228, 230.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 161, 221, 223.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 114, 228.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 1885, 228.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 127, 223, 230.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 130, 227–228.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 151, 228.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 194, 229.

- ^ Dye 1997, pp. 2, 120, 229.

Bibliography

Newspapers and online sources

- "Afong, Chun office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Creamer, Beverly (November 28, 2002). "Ballet dancer Tessa Dye, who toured Asia and Europe, dead at 56". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Gee, Pat (November 27, 2002). "Tessa Gay Dye / Magoon Estate Director: Ballerina embraced family life, community service". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu.

- Gomes, Andrew (February 3, 2010). "Nuʻuanu restaurant closes doors". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Gonser, James (December 22, 2005). "Tree planted in 1870s cut down". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Hawaii. Minutes of the Privy Council, 1875–1881. Honolulu: Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law, William S. Richardson School of Law. Archived from the original on May 31, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hoover, Will (October 19, 2009). "Plaza's trees part of Isle lore". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Liang, Ling (December 6, 2012). "Meixi Memorial Archways". China Highlights. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Prats, J. J.; Miller, Richard E.; Pfingsten, Bill, eds. (November 16, 2008). "Afong Villa — Waikīkī Historic Trail". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- Sigall, Bob (July 26, 2013). "Chun Afong arrived in 1849 and got right to business". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Sigall, Bob (August 2, 2013). "The Hungry Lion lived large at shopping plaza". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Sigall, Bob (May 1, 2015). "Chinese businesses enjoy profitable history in Hawaii". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Honolulu.

- Travel China Guide. "Meixi Archways Scenic Area (Meixi Paifang Scenic Area)". Travel China Guide. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Tsai, Michael (February 7, 2010). "Dye, Suwa: Isle visionaries". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu.

Books and journals

- Alexander, William DeWitt (1896). History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Revolution of 1893. Honolulu: Hawaiian Gazette Company. OCLC 11843616.

- Char, Wai-Jane (1974). "Chinese Merchant-Adventurers and Sugar Masters in Hawaii: 1802–1852: General Background" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. 8. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 3–10. hdl:10524/132. OCLC 60626541.

- Chou, Michaelyn P. (2010). "Ethnicity and Elections in Hawaiʻi: The Case of James K. Kealoha" (PDF). Chinese America: History & Perspectives. 15. San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America with UCLA Asian American Studies Center: 105–111. OCLC 818922702.

- Day, Arthur Grove (1984). History Makers of Hawaii: a Biographical Dictionary. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing of Honolulu. ISBN 978-0-935180-09-1. OCLC 11087565.

- Day, Arthur Grove (1987). Mad About Islands: Novelists Of A Vanished Pacific. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing. ISBN 978-0-935180-46-6. OCLC 17445516.

- Dye, Bob (1994). "Great Chinese Merchants' Ball of 1856" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. 28. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 69–78. hdl:10524/124. OCLC 60626541.

- Dye, Bob (1997). Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains: Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1772-5. OCLC 247424976.

- Dye, Robert Paul (2010). "Merchant Prince: Chun Afong in Hawaiʻi, 1849–90" (PDF). Chinese America: History & Perspectives. 15. San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America with UCLA Asian American Studies Center: 23–36. OCLC 818922702.

- Glick, Clarence E. (1980). Sojourners and Settlers: Chinese Migrants in Hawaii (PDF). Honolulu: Hawaii Chinese History Center and University Press of Hawaii. hdl:10125/45047. ISBN 978-0-8248-0707-8. OCLC 6222806.

- Chun Fong (Afong), 2, 48, 115, 181, 204, 268, 332 n.30, 349 n.41, 349 n.42;

- Higgins, James Edgar (1917). The Litchi in Hawaii (PDF). Bulletin (Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station), no. 44. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:10125/9172. OCLC 10055912.

- Kauanui, J. Kēhaulani; Kauanui, J. Kehaulani (2008). Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9149-4. OCLC 308649636.

- Lam, Margaret M. (1932). Six Generations of Race Mixture in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Sociology MA Thesis. OCLC 16325277.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. OCLC 500374815.

- Lim-Chong, Lily; Ball, Harry V. (2010). "Opium and the Law: Hawaiʻi, 1856–1900" (PDF). Chinese America: History & Perspectives – the Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America. San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America with UCLA Asian American Studies Center: 61–74. OCLC 679402743.

- Lin, Tianwei (1991). 亞太地方文獻硏究論文集: Contribution of Overseas Chinese. Hong Kong: Center of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong. OCLC 607264493.

- Ng, Franklin (1999). "Chun Afong". In Kim, Hyung-chan (ed.). Distinguished Asian Americans: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-0-313-28902-6. OCLC 237359631.

- Pang, Loretta (1998). "Book Reviews: Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains: Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. 32. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 210–215. hdl:10524/194. OCLC 60626541.

- Zee, Francis; Nagao, Mike; Nishina, Melvin; Kawabat, Andrew (June 1999). "Growing Lychee in Hawaii" (PDF). Fruits and Nuts (2). Honolulu: Cooperative Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources: 1–8. hdl:10125/2346. OCLC 43783936.

Further reading

- Char, Tin-Yuke (1975). The Sandalwood Mountains: Readings and Stories of the Early Chinese in Hawaii. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-0305-6. OCLC 1091892.

- Char, Tin-Yuke (1980). Chinese Historic Sites and Pioneer Families of Kauai. Honolulu: Hawaii Chinese History Center. OCLC 6831849.

- Char, Tin-Yuke; Char, Wai Jane (1983). Chinese Historic Sites and Pioneer Families of the Island of Hawaii. Honolulu: Published for the Hawaii Chinese History Center by University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0863-1. OCLC 255259005.

- Char, Wai J.; Char, Tin-Uke (1988). Chinese Historic Sites and Pioneer Families of Rural Oahu. Honolulu: Hawaii Chinese History Center. ISBN 978-0-8248-1113-6. OCLC 17299656.

- London, Jack (1912). "Chun Ah Chun". The House of Pride: And Other Tales of Hawaii. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 149–189. OCLC 13369633.

- Taylor, Clarice B. (October 7 – December 25, 1953). "Tales About Hawaii: The Story of the Afong Family (Summaries)" (PDF). Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Nos. 1–69. Honolulu – via Kauai Historical Society.

- Young, Nancy Foon (1973). The Chinese in Hawaii: An Annotated Bibliography (PDF). Hawaii Series No. 4. Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii. hdl:10125/42156. ISBN 978-0-8248-0265-3. OCLC 858604.

External links

- "Chun Afong's Residence & Museum, Meixi, Guangdong Province, China". Flickr. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Young, Peter T. (January 4, 2013). "Chen Fang – Chun Afong". Image of Old Hawaiʻi. Hoʻokuleana LLC. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Young, Peter T. (May 18, 2013). "Julia Fayerweather Afong". Image of Old Hawaiʻi. Hoʻokuleana LLC. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Young, Peter T. (June 30, 2014). "J. Alfred Magoon". Image of Old Hawaiʻi. Hoʻokuleana LLC. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- 卓海玉. "陈芳:最早走进全球化时代的中国人 – 首席执行官 – 世界经理人 (Chen Fang: the first Chinese to enter the era of Globalization)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2017.