Chinese numerals

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Chinese numerals are words and characters used to denote numbers in written Chinese.

Today, speakers of Chinese languages use three written numeral systems: the system of Arabic numerals used worldwide, and two indigenous systems. The more familiar indigenous system is based on Chinese characters that correspond to numerals in the spoken language. These may be shared with other languages of the Chinese cultural sphere such as Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese. Most people and institutions in China primarily use the Arabic or mixed Arabic-Chinese systems for convenience, with traditional Chinese numerals used in finance, mainly for writing amounts on cheques, banknotes, some ceremonial occasions, some boxes, and on commercials.[citation needed]

The other indigenous system consists of the Suzhou numerals, or huama, a positional system, the only surviving form of the rod numerals. These were once used by Chinese mathematicians, and later by merchants in Chinese markets, such as those in Hong Kong until the 1990s, but were gradually supplanted by Arabic numerals.

Basic counting in Chinese

The Chinese character numeral system consists of the Chinese characters used by the Chinese written language to write spoken numerals. Similar to spelling-out numbers in English (e.g., "one thousand nine hundred forty-five"), it is not an independent system per se. Since it reflects spoken language, it does not use the positional system as in Arabic numerals, in the same way that spelling out numbers in English does not.

Ordinary numerals

There are characters representing the numbers zero through nine, and other characters representing larger numbers such as tens, hundreds, thousands, ten thousands and hundred millions. There are two sets of characters for Chinese numerals: one for everyday writing, known as xiǎoxiě (小寫; 小写; 'small writing'), and one for use in commercial, accounting or financial contexts, known as dàxiě (大寫; 大写; 'big writing' or 'capital numbers'). The latter were developed by Wu Zetian (fl. 690–705) and were further refined by the Hongwu Emperor (fl. 1328–1398).[1] They arose because the characters used for writing numerals are geometrically simple, so simply using those numerals cannot prevent forgeries in the same way spelling numbers out in English would.[2] A forger could easily change the everyday characters 三十 (30) to 五千 (5000) just by adding a few strokes. That would not be possible when writing using the financial characters 參拾 (30) and 伍仟 (5000). They are also referred to as "banker's numerals" of "anti-fraud numerals". For the same reason, rod numerals were never used in commercial records.

| Value | Financial | Ordinary | Pinyin (Mandarin) | Jyutping (Cantonese) | Tâi-lô (Hokkien) | Wugniu (Wu) | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Simplified[3]: §52 | Traditional | Simplified | ||||||

| 0 | 零 | 零 or 〇 | líng | ling4 | khòng, lêng | lin | Usually 零 is preferred, but in some areas, 〇 may be a more common informal way to represent zero. The original Chinese character is 空 or 〇, 零 is referred as remainder something less than 1 yet not nil [說文] referred. The traditional 零 is more often used in schools. In Unicode, 〇 is treated as a Chinese symbol or punctuation, rather than a Chinese ideograph. | ||

| 1 | 壹 | 一 | yī | jat1 | it, tsi̍t | iq | Also 弌 (obsolete financial), can be easily manipulated into 弍; 'two' or 弎; 'three'. | ||

| 2 | 貳 | 贰 | 二 | èr | ji6 | jī, nn̄g | gni, er, lian | Also 弍 (obsolete, financial), can be easily manipulated into 弌; 'one' or 弎; 'three'. Also 两; 兩. | |

| 3 | 參 | 叁 | 三 | sān | saam1 | sam, sann | sé | Also 弎 (obsolete financial), which can be easily manipulated into 弌; 'one' or 弍; 'two'. | |

| 4 | 肆 | 四 | sì | sei3 | sù, sì | sy | Also 䦉 (obsolete financial).[nb 1] | ||

| 5 | 伍 | 五 | wǔ | ng5 | ngóo, gōo | ng | — | ||

| 6 | 陸 | 陆 | 六 | liù | luk6 | liok, la̍k | loq | — | |

| 7 | 柒 | 七 | qī | cat1 | tshit | chiq | — | ||

| 8 | 捌 | 八 | bā | baat3 | pat, peh | paq | — | ||

| 9 | 玖 | 九 | jiǔ | gau2 | kiú, káu | cieu | — | ||

| 10 | 拾 | 十 | shí | sap6 | si̍p, tsa̍p | zeq | Although some people use 什 as financial[citation needed], it is not ideal because it can be easily manipulated into 伍; 'five' or 仟; 'thousand'. | ||

| 100 | 佰 | 百 | bǎi | baak3 | pek, pah | paq | — | ||

| 1,000 | 仟 | 千 | qiān | cin1 | tshian, tsheng | chi | — | ||

| 104 | 萬 | 万 | 萬 | 万 | wàn | maan6 | bān | ve | Chinese numbers group by ten-thousands; see Reading and transcribing numbers below. |

| 108 | 億 | 亿 | 億 | 亿 | yì | jik1 | ik | i | For variant meanings and words for higher values, see Large numbers below. |

Regional usage

| Financial | Normal | Value | Pinyin | Standard alternative | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 空 | 0 | kòng | 零 | Historically, the use of 空 for 'zero' predates 零. This is now archaic in most varieties of Chinese, but it is still used in most of Southern Min. | |

| 洞 | 0 | dòng | 零 | Literally 'a hole', is analogous to the shape of ⟨0⟩ and ⟨〇⟩, it is used to unambiguously pronounce #0 in radio communication.[4][5] | |

| 幺 | 1 | yāo | 一 | Literally 'the smallest', it is used to unambiguously pronounce #1 in radio communication.[4][5] This usage is not observed in Cantonese except for 十三幺, which refers to a special winning hand in mahjong. | |

| 蜀 | 1 | shǔ | 一 | In most Min varieties, there are two words meaning 'one'. For example, in Hokkien, chi̍t is used before a classifier: 'one person' is chi̍t ê lâng, not it ê lâng. In written Hokkien, 一 is often used for both chi̍t and it, but some authors differentiate, writing 蜀 for chi̍t and 一 for it. | |

| 两; 兩 | 2 | liǎng | 二 | Used instead of 二 before a classifier. For example, 'two people' is 两个人, not 二个人. However, in some lects such as Shanghainese, 兩 is the generic term used for two in most contexts, such as 四十兩 and not 四十二. It appears where 'a pair of' might in English, but 两 is always used in such cases. It is also used for numbers, with usage varying from dialect to dialect, even person to person. For example, '2222' can be read as 二千二百二十二, 兩千二百二十二, or even 兩千兩百二十二 in Mandarin. It is used to unambiguously pronounce #2 in radio communication.[4][5] | |

| 俩; 倆 | 2 | liǎ | 兩 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 倆 represents a "lazy" pronunciation of 兩 within the local dialect. It can be used as an alternative for 兩个; 'two of', e.g. 我们倆; wǒmen liǎ; 'the two of us', as opposed to 我们兩个; wǒmen liǎng gè. A measure word never follows 倆. | |

| 仨 | 3 | sā | 三 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 仨 represents a "lazy" pronunciation of three within the local dialect. It can be used as a general number to represent 'three', e.g.第仨号; dìsāhào; 'number three'; 星期仨; xīngqīsā; 'Wednesday', or as an alternative for 三个; 'three of', e.g. 我们仨; wǒmen sā; 'the three of us', as opposed to 我们三个; wǒmen sān gè). Regardless of usage, a measure word never follows 仨. | |

| 拐 | 7 | guǎi | 七 | Literally 'a turn' or 'a walking stick' and is analogous to the shape of ⟨7⟩ and 七, it is used to unambiguously pronounce #7 in radio communication.[4][5] | |

| 勾 | 9 | gōu | 九 | Literally 'a hook' and is analogous to the shape of ⟨9⟩, it is used to unambiguously pronounce #9 in radio communication.[4][5] | |

| 呀 | 10 | yà | 十 | In spoken Cantonese, 呀 (aa6) can be used in place of 十 when it is used in the middle of a number, preceded by a multiplier and followed by a ones digit, e.g. 六呀三 '63', it is not used by itself to mean 10. This usage is not observed in Mandarin. | |

| 念 | 廿 | 20 | niàn | 二十 | A contraction of 二十. The written form is still used to refer to dates, especially Chinese calendar dates. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese, 廿 (jaa6) can be used in place of 二十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 21–29 (e.g. 廿三 '23', a measure word, e.g. 廿個, a noun, or in a phrase like 廿幾 'twenty-something'. It is not used by itself to mean 20. 廿; jiāp/gnie6 is still used in place of 二十 in Southern Min and Wu. 卄 is a rare variant. |

| 卅 | 30 | sà | 三十 | A contraction of 三十. The written form is still used to abbreviate date references in Chinese. For example, May 30 Movement (五卅運動). The spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. In spoken Cantonese, 卅; saa1 can be used in place of 三十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 31–39, a measure word (e.g. 卅個), a noun, or in phrases like 卅幾 'thirty-something'. It is not used by itself to mean 30. When spoken 卅 is pronounced as 卅呀; saa1-aa6. Thus 卅一 '31', is pronounced as saa1-aa6-jat1. | |

| 卌 | 40 | xì | 四十 | A contraction of 四十. Found in historical writings written in Literary Chinese. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese, albeit very rare. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese 卌; sei3 can be used in place of 四十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 41–49, a measure word (e.g. 卌個), a noun, or in phrases like 卌幾 'forty-something', it is not used by itself to mean 40. When spoken, 卌 is pronounced as 卌呀; sei3-aa6. Thus 卌一; 41, is pronounced as sei3-aa6-jat1. Similarly, in Southern Min 41 can be referred to as 卌一; siap it. | |

| 皕 | 200 | bì | 二百 | Very rarely used; one example is in the name of a library in Huzhou, 皕宋樓; Bìsòng Lóu. |

Powers of 10

Large numbers

For numbers larger than 10,000, similarly to the long and short scales in the West, there have been four systems in ancient and modern usage. The original one, with unique names for all powers of ten up to the 14th, is ascribed to the Yellow Emperor in the 6th century book by Zhen Luan, Wujing suanshu; 'Arithmetic in Five Classics'. In modern Chinese, only the second system is used, in which the same ancient names are used, but each represents a myriad, 萬; wàn times the previous:

| Character | 萬 | 億 | 兆 | 京 | 垓 | 秭 | 穰 | 溝 | 澗 | 正 | 載 | Factor of increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character (S) | 万 | 亿 | 沟 | 涧 | 载 | |||||||

| Pinyin | wàn | yì | zhào | jīng | gāi | zǐ | ráng | gōu | jiàn | zhèng | zǎi | |

| Jyutping | maan6 | jik1 | siu6 | ging1 | goi1 | zi2 | joeng4 | kau1 | gaan3 | zing3 | zoi2 | |

| Tai Lo | bān | ik | tiāu | king | kai | cí | jiông | koo | kàn | cèng | cáinn | |

| Shanghainese | ve | i | zau | cín | ké | tsy | gnian | kéu | ké | tsen | tse | |

| Alternative | 经; 經 | 𥝱 | 壤 | |||||||||

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | =n |

| "short scale" (下數) | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 1010 | 1011 | 1012 | 1013 | 1014 | =10n+3

Each numeral is 10 (十; shí) times the previous. |

| "myriad scale" (萬進, current usage) | 104 | 108 | 1012 | 1016 | 1020 | 1024 | 1028 | 1032 | 1036 | 1040 | 1044 | =104n

Each numeral is 10,000 (万; 萬; wàn) times the previous. |

| "mid-scale" (中數) | 104 | 108 | 1016 | 1024 | 1032 | 1040 | 1048 | 1056 | 1064 | 1072 | 1080 | =108(n-1)

Starting with 亿, each numeral is 108 (万乘以万; 萬乘以萬; wàn chéngyǐ wàn; '10000 times 10000') times the previous. |

| "long scale" (上數) | 104 | 108 | 1016 | 1032 | 1064 | 10128 | 10256 | 10512 | 101024 | 102048 | 104096 | =102n+1

Each numeral is the square of the previous. This is similar to the -yllion system. |

In practice, this situation does not lead to ambiguity, with the exception of 兆; zhào, which means 1012 according to the system in common usage throughout the Chinese communities as well as in Japan and Korea, but has also been used for 106 in recent years (especially in mainland China for megabyte). To avoid problems arising from the ambiguity, the PRC government never uses this character in official documents, but uses 万亿; wànyì) or 太; tài; 'tera-' instead. Partly due to this, combinations of 万 and 亿 are often used instead of the larger units of the traditional system as well, for example 亿亿; yìyì instead of 京. The ROC government in Taiwan uses 兆; zhào to mean 1012 in official documents.

Large numbers from Buddhism

Numerals beyond 載 zǎi come from Buddhist texts in Sanskrit, but are mostly found in ancient texts. Some of the following words are still being used today, but may have transferred meanings.

| Character | Pinyin | Jyutping | Tai Lo | Shanghainese | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 极; 極 | jí | gik1 | ke̍k | jiq5 | 1048 | Literally 'extreme'. |

| 恒河沙; 恆河沙 | héng hé shā | hang4 ho4 sa1 | hîng-hô-sua | ghen3-wu-so | 1052[citation needed] | Literally 'sands of the Ganges', a metaphor used in a number of Buddhist texts referring to many individual grains of sand |

| 阿僧祇 | ā sēng qí | aa1 zang1 kei4 | a-sing-kî | a1-sen-ji | 1056 | From Sanskrit Asaṃkhyeya असंख्येय 'innumerable', 'infinite' |

| 那由他 | nà yóu tā | naa5 jau4 taa1 | ná-iû-thann | na1-yeu-tha | 1060 | From Sanskrit nayuta नियुत 'myriad' |

| 不可思議; 不可思议 | bùkě sīyì | bat1 ho2 si1 ji3 | put-khó-su-gī | peq4-khu sy1-gni | 1064 | Literally translated as "unfathomable". This word is commonly used in Chinese as a chengyu, meaning "unimaginable", instead of its original meaning of the number 1064. |

| 无量大数; 無量大數 | wú liàng dà shù | mou4 loeng6 daai6 sou3 | bû-liōng tāi-siàu | m3-lian du3-su | 1068 | 无量 literally 'without measure', and can mean 1068. This word is also commonly used in Chinese as a commendatory term, means 'no upper limit'. e.g.: 前途无量 'a great future'. 大数 'a large number', and can mean 1072. |

Small numbers

The following are characters used to denote small order of magnitude in Chinese historically. With the introduction of SI units, some of them have been incorporated as SI prefixes, while the rest have fallen into disuse.

| Characters | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 漠 | mò | 10−12 | (Ancient Chinese) |

| 渺 | miǎo | 10−11 | (Ancient Chinese) |

| 埃 | āi | 10−10 | (Ancient Chinese) |

| 尘; 塵 | chén | 10−9 | Literally 'dust'

纳; 奈 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix nano-. |

| 沙 | shā | 10−8 | Literally, "Sand" |

| 纤; 纖 | xiān | 10−7 | 'fiber' |

| 微 | wēi | 10−6 | still used, corresponds to the SI prefix micro-. |

| 忽 | hū | 10−5 | (Ancient Chinese) |

| 丝; 絲 | sī | 10−4 | also 秒.

Literally, "Thread" |

| 毫 | háo | 10−3 | also 毛.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix milli-. |

| 厘 | lí | 10−2 | also 釐.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix centi-. |

| 分 | fēn | 10−1 | still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix deci-. |

Small numbers from Buddhism

| Characters | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 涅槃寂静; 涅槃寂靜 | niè pán jì jìng | 10−24 | 'Nirvana's tranquillity' |

| 阿摩罗; 阿摩羅 | ā mó luó | 10−23 | From Sanskrit अमल amala |

| 阿赖耶; 阿頼耶 | ā lài yē | 10−22 | From Sanskrit आलय ālaya |

| 清净; 清靜 | qīng jìng | 10−21 | 'quiet'

仄; 介 corresponds to the SI prefix zepto-. |

| 虚空; 虛空 | xū kōng | 10−20 | 'void' |

| 六德 | liù dé | 10−19 | |

| 刹那; 剎那 | chà nà | 10−18 | Literally 'brevity', from Sanskrit क्षण ksaṇa. 阿 corresponds to the SI prefix atto-. |

| 弹指; 彈指 | tán zhǐ | 10−17 | Literally 'flick of a finger'. Still commonly used in the phrase 弹指一瞬间; 'a very short time' |

| 瞬息 | shùn xī | 10−16 | Literally 'moment of breath'. Still commonly used in the chengyu 瞬息万变 'many things changed in a very short time' |

| 须臾; 須臾 | xū yú | 10−15 | Rarely used in modern Chinese as 'a very short time'. 飞; 飛 corresponds to the SI prefix femto-. |

| 逡巡 | qūn xún | 10−14 | |

| 模糊 | mó hu | 10−13 | 'blurred' |

SI prefixes

In the People's Republic of China, the early translation for the SI prefixes in 1981 was different from those used today. The larger (兆, 京, 垓, 秭, 穰) and smaller Chinese numerals (微, 纖, 沙, 塵, 渺) were defined as translation for the SI prefixes as mega, giga, tera, peta, exa, micro, nano, pico, femto, atto, resulting in the creation of yet more values for each numeral.[6]

The Republic of China (Taiwan) defined 百萬 as the translation for mega and 兆 as the translation for tera. This translation is widely used in official documents, academic communities, informational industries, etc. However, the civil broadcasting industries sometimes use 兆赫 to represent "megahertz".

Today, the governments of both China and Taiwan use phonetic transliterations for the SI prefixes. However, the governments have each chosen different Chinese characters for certain prefixes. The following table lists the two different standards together with the early translation.

| Value | Symbol | English | Early translation | PRC standard | ROC standard[7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1030 | Q | quetta- | 昆 | kūn | 昆 | kūn | ||

| 1027 | R | ronna- | 容 | róng | 羅 | luó | ||

| 1024 | Y | yotta- | 尧 | yáo | 佑 | yòu | ||

| 1021 | Z | zetta- | 泽 | zé | 皆 | jiē | ||

| 1018 | E | exa- | 穰[6] | ráng | 艾 | ài | 艾 | ài |

| 1015 | P | peta- | 秭[6] | zǐ | 拍 | pāi | 拍 | pāi |

| 1012 | T | tera- | 垓[6] | gāi | 太 | tài | 兆 | zhào |

| 109 | G | giga- | 京[6] | jīng | 吉 | jí | 吉 | jí |

| 106 | M | mega- | 兆[6] | zhào | 兆 | zhào | 百萬 | bǎiwàn |

| 103 | k | kilo- | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān |

| 102 | h | hecto- | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi |

| 101 | da | deca- | 十 | shí | 十 | shí | 十 | shí |

| 100 | (base) | one | 一 | yī | 一 | yī | ||

| 10−1 | d | deci- | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn |

| 10−2 | c | centi- | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí |

| 10−3 | m | milli- | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo |

| 10−6 | μ | micro- | 微[6] | wēi | 微 | wēi | 微 | wēi |

| 10−9 | n | nano- | 纖[6] | xiān | 纳 | nà | 奈 | nài |

| 10−12 | p | pico- | 沙[6] | shā | 皮 | pí | 皮 | pí |

| 10−15 | f | femto- | 塵[6] | chén | 飞 | fēi | 飛 | fēi |

| 10−18 | a | atto- | 渺[6] | miǎo | 阿 | à | 阿 | à |

| 10−21 | z | zepto- | 仄 | zè | 介 | jiè | ||

| 10−24 | y | yocto- | 幺 | yāo | 攸 | yōu | ||

| 10−27 | r | ronto- | 柔 | róu | 絨 | róng | ||

| 10−30 | q | quecto- | 亏 | kuī | 匱 | kuì | ||

Reading and transcribing numbers

Whole numbers

Multiple-digit numbers are constructed using a multiplicative principle; first the digit itself (from 1 to 9), then the place (such as 10 or 100); then the next digit.

In Mandarin, the multiplier 兩 (liǎng) is often used rather than 二; èr for all numbers 200 and greater with the "2" numeral (although as noted earlier this varies from dialect to dialect and person to person). Use of both 兩; liǎng or 二; èr are acceptable for the number 200. When writing in the Cantonese dialect, 二; yi6 is used to represent the "2" numeral for all numbers. In the southern Min dialect of Chaozhou (Teochew), 兩 (no6) is used to represent the "2" numeral in all numbers from 200 onwards. Thus:

| Number | Structure | Characters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | Cantonese | Chaozhou | Shanghainese | ||

| 60 | [6] [10] | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 |

| 20 | [2] [10] or [20] | 二十 | 二十 or 廿 | 二十 | 廿 |

| 200 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [100] | 二百 or 兩百 | 二百 or 兩百 | 兩百 | 兩百 |

| 2000 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [1000] | 二千 or 兩千 | 二千 or 兩千 | 兩千 | 兩千 |

| 45 | [4] [10] [5] | 四十五 | 四十五 or 卌五 | 四十五 | 四十五 |

| 2,362 | [2] [1000] [3] [100] [6] [10] [2] | 兩千三百六十二 | 二千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 |

For the numbers 11 through 19, the leading 'one' (一; yī) is usually omitted. In some dialects, like Shanghainese, when there are only two significant digits in the number, the leading 'one' and the trailing zeroes are omitted. Sometimes, the one before "ten" in the middle of a number, such as 213, is omitted. Thus:

| Number | Strict Putonghua | Colloquial or dialect usage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Characters | Structure | Characters | |

| 14 | [10] [4] | 十四 | ||

| 12000 | [1] [10000] [2] [1000] | 一萬兩千 | [1] [10000] [2] | 一萬二 or 萬二 |

| 114 | [1] [100] [1] [10] [4] | 一百一十四 | [1] [100] [10] [4] | 一百十四 |

| 1158 | [1] [1000] [1] [100] [5] [10] [8] | 一千一百五十八 | ||

Notes:

- Nothing is ever omitted in large and more complicated numbers such as this.

In certain older texts like the Protestant Bible, or in poetic usage, numbers such as 114 may be written as [100] [10] [4] (百十四).

Outside of Taiwan, digits are sometimes grouped by myriads instead of thousands. Hence it is more convenient to think of numbers here as in groups of four, thus 1,234,567,890 is regrouped here as 12,3456,7890. Larger than a myriad, each number is therefore four zeroes longer than the one before it, thus 10000 × 萬; wàn = 億; yì. If one of the numbers is between 10 and 19, the leading 'one' is omitted as per the above point. Hence (numbers in parentheses indicate that the number has been written as one number rather than expanded):

| Number | Structure | Taiwan | Mainland China |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,345,678,902,345 (12,3456,7890,2345) | (12) [1,0000,0000,0000] (3456) [1,0000,0000] (7890) [1,0000] (2345) | 十二兆三千四百五十六億七千八百九十萬兩千三百四十五 | 十二兆三千四百五十六亿七千八百九十万二千三百四十五 |

In Taiwan, pure Arabic numerals are officially always and only grouped by thousands.[8] Unofficially, they are often not grouped, particularly for numbers below 100,000. Mixed Arabic-Chinese numerals are often used in order to denote myriads. This is used both officially and unofficially, and come in a variety of styles:

| Number | Structure | Mixed numerals |

|---|---|---|

| 12,345,000 | (1234) [1,0000] (5) [1,000] | 1,234萬5千[9] |

| 123,450,000 | (1) [1,0000,0000] (2345) [1,0000] | 1億2345萬[10] |

| 12,345 | (1) [1,0000] (2345) | 1萬2345[11] |

Interior zeroes before the unit position (as in 1002) must be spelt explicitly. The reason for this is that trailing zeroes (as in 1200) are often omitted as shorthand, so ambiguity occurs. One zero is sufficient to resolve the ambiguity. Where the zero is before a digit other than the units digit, the explicit zero is not ambiguous and is therefore optional, but preferred. Thus:

| Number | Structure | Characters |

|---|---|---|

| 205 | [2] [100] [0] [5] | 二百零五 |

| 100,004(10,0004) | [10] [10,000] [0] [4] | 十萬零四 |

| 10,050,026(1005,0026) | (1005) [10,000] (026) or (1005) [10,000] (26) | 一千零五萬零二十六 or 一千零五萬二十六 |

Fractional values

To construct a fraction, the denominator is written first, followed by 分; fēn; 'part', then the literary possessive particle 之; zhī; 'of this', and lastly the numerator. This is the opposite of how fractions are read in English, which is numerator first. Each half of the fraction is written the same as a whole number. For example, to express "two thirds", the structure "three parts of-this two" is used. Mixed numbers are written with the whole-number part first, followed by 又; yòu; 'and', then the fractional part.

| Fraction | Structure |

|---|---|

| 2⁄3 | 三 sān 3 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 二 èr 2 |

| 15⁄32 | 三 sān 3 十 shí 10 二 èr 2 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 |

| 1⁄3000 | 三 sān 3 千 qiān 1000 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 一 yī 1 |

| 3 5⁄6 | 三 sān 3 又 yòu and 六 liù 6 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 五 wǔ 5 |

Percentages are constructed similarly, using 百; bǎi; '100' as the denominator. (The number 100 is typically expressed as 一百; yībǎi; 'one hundred', like the English 'one hundred'. However, for percentages, 百 is used on its own.)

| Percentage | Structure |

|---|---|

| 25% | 百 bǎi 100 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 二 èr 2 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 |

| 110% | 百 bǎi 100 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 一 yī 1 百 bǎi 100 一 yī 1 十 shí 10 |

Because percentages and other fractions are formulated the same, Chinese are more likely than not to express 10%, 20% etc. as 'parts of 10' (or 1/10, 2/10, etc. i.e. 十分之一; shí fēnzhī yī, 十分之二; shí fēnzhī èr, etc.) rather than "parts of 100" (or 10/100, 20/100, etc. i.e. 百分之十; bǎi fēnzhī shí, 百分之二十; bǎi fēnzhī èrshí, etc.)

In Taiwan, the most common formation of percentages in the spoken language is the number per hundred followed by the word 趴; pā, a contraction of the Japanese パーセント; pāsento, itself taken from 'percent'. Thus 25% is 二十五趴; èrshíwǔ pā.[nb 2]

Decimal numbers are constructed by first writing the whole number part, then inserting a point (点; 點; diǎn), and finally the fractional part. The fractional part is expressed using only the numbers for 0 to 9, similarly to English.

| Decimal expression | Structure |

|---|---|

| 16.98 | 十 shí 10 六 liù 6 點 diǎn point 九 jiǔ 9 八 bā 8 |

| 12345.6789 | 一 yī 1 萬 wàn 10000 兩 liǎng 2 千 qiān 1000 三 sān 3 百 bǎi 100 四 sì 4 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 點 diǎn point 六 liù 6 七 qī 7 八 bā 8 九 jiǔ 9 |

| 75.4025 | 七 七 qī 7 十 十 shí 10 五 五 wǔ 5 點 點 diǎn point 四 四 sì 4 〇 零 líng 0 二 二 èr 2 五 五 wǔ 5 |

| 0.1 | 零 líng 0 點 diǎn point 一 yī 1 |

半; bàn; 'half' functions as a number and therefore requires a measure word. For example: 半杯水; bàn bēi shuǐ; 'half a glass of water'.

Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers are formed by adding 第; dì; 'sequence' before the number.

| Ordinal | Structure |

|---|---|

| 1st | 第 dì sequence 一 yī 1 |

| 2nd | 第 dì sequence 二 èr 2 |

| 82nd | 第 dì sequence 八 bā 8 十 shí 10 二 èr 2 |

The Heavenly Stems are a traditional Chinese ordinal system.

Negative numbers

Negative numbers are formed by adding 负; 負; fù before the number.

| Number | Structure |

|---|---|

| −1158 | 負 fù negative 一 yī 1 千 qiān 1000 一 yī 1 百 bǎi 100 五 wǔ 5 十 shí 10 八 bā 8 |

| −3 5/6 | 負 fù negative 三 sān 3 又 yòu and 六 liù 6 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 五 wǔ 5 |

| −75.4025 | 負 fù negative 七 qī 7 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 點 diǎn point 四 sì 4 零 líng 0 二 èr 2 五 wǔ 5 |

Usage

Chinese grammar requires the use of classifiers (measure words) when a numeral is used together with a noun to express a quantity. For example, "three people" is expressed as 三个人; 三個人; sān ge rén, "three (ge particle) person", where 个/個 ge is a classifier. There exist many different classifiers, for use with different sets of nouns, although 个/個 is the most common, and may be used informally in place of other classifiers.

Chinese uses cardinal numbers in certain situations in which English would use ordinals. For example, 三楼/三樓; sān lóu (literally "three story/storey") means "third floor" ("second floor" in British § Numbering). Likewise, 二十一世纪/二十一世紀; èrshí yī shìjì (literally "twenty-one century") is used for "21st century".[12]

Numbers of years are commonly spoken as a sequence of digits, as in 二零零一; èr líng líng yī ("two zero zero one") for the year 2001.[13] Names of months and days (in the Western system) are also expressed using numbers: 一月; yīyuè ("one month") for January, etc.; and 星期一; xīngqīyī ("week one") for Monday, etc. There is only one exception: Sunday is 星期日; xīngqīrì, or informally 星期天; xīngqītiān, both literally "week day". When meaning "week", "星期" xīngqī and "禮拜; 礼拜" lǐbài are interchangeable. "禮拜天" lǐbàitiān or "禮拜日" lǐbàirì means "day of worship". Chinese Catholics call Sunday "主日" zhǔrì, "Lord's day".[14]

Full dates are usually written in the format 2001年1月20日 for January 20, 2001 (using 年; nián "year", 月; yuè "month", and 日; rì "day") – all the numbers are read as cardinals, not ordinals, with no leading zeroes, and the year is read as a sequence of digits. For brevity the nián, yuè and rì may be dropped to give a date composed of just numbers. For example "6-4" in Chinese is "six-four", short for "month six, day four" i.e. June Fourth, a common Chinese shorthand for the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests (because of the violence that occurred on June 4). For another example 67, in Chinese is sixty seven, short for year nineteen sixty seven, a common Chinese shorthand for the Hong Kong 1967 leftist riots.

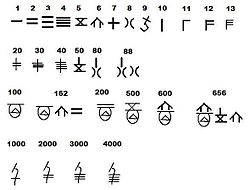

Counting rod and Suzhou numerals

In the same way that Roman numerals were standard in ancient and medieval Europe for mathematics and commerce, the Chinese formerly used the rod numerals, which is a positional system. The Suzhou numerals (simplified Chinese: 苏州花码; traditional Chinese: 蘇州花碼; pinyin: Sūzhōu huāmǎ) system is a variation of the Southern Song rod numerals. Nowadays, the huāmǎ system is only used for displaying prices in Chinese markets or on traditional handwritten invoices.

Hand gestures

There is a common method of using of one hand to signify the numbers one to ten. While the five digits on one hand can easily express the numbers one to five, six to ten have special signs that can be used in commerce or day-to-day communication.

Historical use of numerals in China

Most Chinese numerals of later periods were descendants of the Shang dynasty oracle numerals of the 14th century BC. The oracle bone script numerals were found on tortoise shell and animal bones. In early civilizations, the Shang were able to express any numbers, however large, with only nine symbols and a counting board though it was still not positional.[16]

Some of the bronze script numerals such as 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, and 13 became part of the system of rod numerals.

In this system, horizontal rod numbers are used for the tens, thousands, hundred thousands etc. It is written in Sunzi Suanjing that "one is vertical, ten is horizontal".[17]

| 七 | 一 | 八 | 二 | 四 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

The counting rod numerals system has place value and decimal numerals for computation, and was used widely by Chinese merchants, mathematicians and astronomers from the Han dynasty to the 16th century.

In 690 AD, Wu Zetian promulgated Zetian characters, one of which was 〇. The word is now used as a synonym for the number zero.[nb 3]

Alexander Wylie, Christian missionary to China, in 1853 already refuted the notion that "the Chinese numbers were written in words at length", and stated that in ancient China, calculation was carried out by means of counting rods, and "the written character is evidently a rude presentation of these". After being introduced to the rod numerals, he said "Having thus obtained a simple but effective system of figures, we find the Chinese in actual use of a method of notation depending on the theory of local value [i.e. place-value], several centuries before such theory was understood in Europe, and while yet the science of numbers had scarcely dawned among the Arabs."[18]

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (after Arabic numerals were introduced into China), some Chinese mathematicians used Chinese numeral characters as positional system digits. After the Qing period, both the Chinese numeral characters and the Suzhou numerals were replaced by Arabic numerals in mathematical writings.

Cultural influences

Traditional Chinese numeric characters are also used in Japan and Korea and were used in Vietnam before the 20th century. In vertical text (that is, read top to bottom), using characters for numbers is the norm, while in horizontal text, Arabic numerals are most common. Chinese numeric characters are also used in much the same formal or decorative fashion that Roman numerals are in Western cultures. Chinese numerals may appear together with Arabic numbers on the same sign or document.

See also

Notes

- ^ Variant Chinese character of 肆, with a 镸 radical next to a 四 character. Not all browsers may be able to display this character, which forms a part of the Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Extension A group.

- ^ This usage can also be found in written sources, such as in the headline of this article (while the text uses "%") and throughout this article.

- ^ The code for the lowercase 〇 (IDEOGRAPHIC NUMBER ZERO) is U+3007, not to be confused with the O mark (CIRCLE).

References

- ^ Guo, Xianghe (2009-07-27). "武则天为反贪发明汉语大写数字——中新网" [Wu Zetian invented Chinese capital numbers to fight corruption]. 中新社 [China News Service]. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ 大寫數字「 Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "会计基础工作规范". 广东省会计信息服务平台.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Suming (18 March 2016). Qiao, Meng (ed.). ""军语"里的那些秘密 武警少将亲自为您揭开" [Secrets in the "Military Lingo", Reveled by PAP General]. People's Armed Police. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ^ a b c d e 飛航管理程序 [Air Traffic Management Procedures] (14 ed.). 30 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k (in Chinese) 1981 Gazette of the State Council of the People's Republic of China Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, No. 365 Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, page 575, Table 7: SI prefixes

- ^ "法定度量衡單位及前綴詞" (PDF). bsmi.gov.tw. 31 October 2023. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2024.

- ^ 中華民國統計資訊網(專業人士). 中華民國統計資訊網 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ 中華民國統計資訊網(專業人士) (in Chinese). 中華民國統計資訊網. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "石化氣爆 高市府代位求償訴訟中". 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. 31 July 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "陳子豪雙響砲 兄弟連2天轟猿動紫趴". 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. 30 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don, Chinese: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don, Chinese: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, 2004, p. 13.

- ^ "Days of the Week in Chinese: Three Different Words for 'Week'". Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Mongolian Language Site. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- ^ The Shorter Science & Civilisation in China Vol 2, An abridgement by Colin Ronan of Joseph Needham's original text, Table 20, p. 6, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-23582-0

- ^ The Shorter Science & Civilisation in China Vol 2, An abridgement by Colin Ronan of Joseph Needham's original text, p5, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-23582-0

- ^ Chinese Wikisource Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine 孫子算經: 先識其位, 一從十橫, 百立千僵, 千十相望, 萬百相當.

- ^ Alexander Wylie, Jottings on the Sciences of the Chinese, North Chinese Herald, 1853, Shanghai