Geology of Kansas

The geology of Kansas encompasses the geologic history and the presently exposed rock and soil. Rock that crops out in the US state of Kansas was formed during the Phanerozoic eon, which consists of three geologic eras: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Paleozoic rocks at the surface in Kansas are primarily from the Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian periods.

Paleozoic Era

The oldest rocks at the surface in Kansas are Mississippian rocks that consist of limestones, shale, dolomite, chert, sandstones, and siltstones. The Mississippian consisted of an environment similar to present. Fast-moving streams and rivers cut into the limestone bedrock, and in some places, create caverns and sinkholes.[2] Pennsylvanian rocks consist predominantly of alternating marine and non-marine shales and limestones with some sandstone, coal, chert, and conglomerate. The Pennsylvanian was a time when the region that is now eastern Kansas stayed nearly at sea level. Between the transgression and regression of the seas, swamps, and bogs formed, depositing dead vegetation and later, after burial under younger sediments, this dead vegetation formed into coal.[2] Permian rocks predominantly consist of limestones, shales, and evaporites. The Permian in Kansas began as an environment consisting of warm, shallow seas. As the Permian progressed, the climate became very dry and the seas began to subside, creating bodies of water shut off from the open seas, in turn creating areas for the generation of dark shales and evaporite minerals such as halite and gypsum as the waters evaporated.[2] The end of the Permian marks the largest extinction period in Earth's history; over 90% of all life disappeared.

Mesozoic Era

Mesozoic rocks at the surface of Kansas consist predominantly of rocks from the Cretaceous. A relatively small outcrop of Jurassic sediments is exposed in the southwest corner of the state. Cretaceous age rocks consist of limestone, chalk, shale, and sandstone. The Cretaceous in Kansas was an open ocean or sea environment dominated by microscopic marine plants and animals that floated or swam near the surface of this ancient water body.[2] As these microscopic creatures died, they sank to the bottom, formed a soft, limy ooze, and would preserve any larger creatures that died and sank into it.

Cenozoic Era

Cenozoic rocks at the surface were formed during the Paleogene, Neogene, and Quaternary periods. Paleogene to Neogene rocks in Kansas consist of river silt, sand, freshwater limestones, and some volcanic ash derived from eruptions in the western United States. Near the beginning of the Paleogene, the Rocky Mountains were formed, as were the streams and rivers heading eastward out from the mountains into Kansas. Over 60 million years of erosion, the Rocky Mountains created a wedge of material extending to the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas.[2] Quaternary rocks in Kansas consist of these: glacial drift; river silt, sand, and gravel; dune sand; and wind-blown silt. The Quaternary Period in western Kansas was very similar to the Neogene, continual erosion of the Rocky Mountains deposited additional sediments.[2]

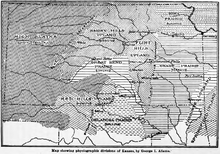

Physiographic regions

Kansas has been divided into eleven different physiographic regions.[4]

Ozark plateau

Mississippian limestones and cherts of the Ozark Plateau are exposed in extreme southeastern Kansas in Cherokee County.[5] This area was part of the Tri-state district of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Galena was a center of lead and zinc mining in the area.[6]

Cherokee lowlands

The Cherokee lowlands is a region of southeast Kansas immediately north and west of the Ozark plateau in Cherokee, Labette, Crawford and Bourbon Counties. The lowlands are developed on areas of gently rolling hills developed on the shale and sandstone of the Cherokee Group of the Pennsylvanian age. The Cherokee Group is noted for rich deposits of coal in Kansas and across the midwestern United States.[7]

Osage Cuestas

The Osage cuesta region underlies twenty counties in southeastern Kansas. The cuestas are a region of east to southeast facing escarpments (50 to 200 feet [15 to 61 m] high) formed on resistant limestone units which dip gently to the west and northwest. Areas between escarpments are underlain by shales. The cuesta region contains coal, black shale and some oil shales. Lamproite sills occur within the cuesta units of Woodson and Wilson counties. These unusual igneous rocks were intruded in the Cretaceous Period.[8][9]

Chautauqua Hills

The Chautauqua Hills represent a narrow region in southeast Kansas of sandstone-capped ridges and rolling hills. The Pennsylvanian age sandstones were deposited in a large river valley. The sandstones are the Tonganoxie Sandstone Member of the Stranger Formation and the Ireland Sandstone Member of the Lawrence Formation. The hills occur in the western portions of Montgomery, Wilson and Woodson counties and the eastern edges of Chautauqua, Elk and Greenwood counties. The sandstones continue into northern Oklahoma.[10]

Flint Hills

The Flint Hills developed on the north–south exposure of Permian cherty limestones. The region extends from Marshall County in the north, to Cowley County and on into northern Oklahoma where they are known as the Osage Hills. The Permian limestones contain abundant weathering resistant chert (or flint) and the residuum and soils of the hilltops and the streambeds of the region contain abundant cherty gravels. Surface exposures of the rare igneous kimberlites occur in Riley and Marshall counties. The kimberlite diatremes are of Cretaceous age. No diamonds have been found in the Kansas kimberlite occurrences. Garnet crystals from the kimberlites have been reported in local stream gravels.[11][12][13]

Red Hills

The Red Hills cover a section of southern Kansas in Clark, Comanche, and Barber counties along the Oklahoma border. The Red Hills are named for their color derived from the Permian red beds which outcrop and underlie the region. The red color is produced by abundant iron oxides in the weathering sediments. The region is underlain by red shales, siltstones, and sandstones along with interbedded dolomites and gypsum evaporite layers. Massive gypsum deposits are mined near Sun City in northwestern Barber County. The Gyp Hills near Medicine Lodge were named for the gypsum of the Blaine Formation. The soluble gypsum, anhydrite and dolomite produce many caves in the area.[14][15] The Big Basin of Clark County is a 1.2-mile (2 km) diameter, 115-foot (35 m) deep, dissolution collapse feature that formed by the dissolution of salt beds in the subsurface.

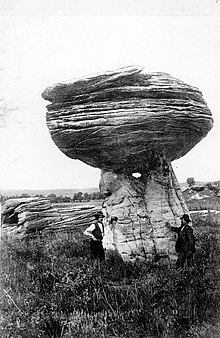

Smoky Hills

The Smoky Hills constitute a large area of north central Kansas. The area is underlain by Cretaceous sediments. Rocks outcropping in the area include the sandstones of the Dakota Formation, the Greenhorn Limestone, and the thick Niobrara Chalk. Stratigraphically the Dakota is overlain by the Greenhorn and that by the Niobrara. The Dakota outcrops in the eastern portion of the region as gently westward dipping resistant ridges. Although the sandstones are the most resistant and therefore most prominent the Dakota includes shales and clays. The formation contains abundant brown iron oxides and many concretions are found in the area. In the western portions of the area, the bedrock is fossiliferous chalk of the Niobrara Formation which includes the Smoky Hill Chalk member noted for abundant fish and marine reptile fossils.[16][17]

High Plains

The western third of Kansas is in the High Plains area. The highest point in Kansas, Mount Sunflower (4,039 feet (1,231 m)), is located in the High Plains physiographic region. The tectonic uplift of the Rocky Mountains during the Cenozoic resulted in erosion and deposition of vast quantities of non-marine sediments eastward across the High Plains. The Ogallala Formation consists of a large wedge of unconsolidated sands and silts that is a significant aquifer under the plains. The Ogallala contains a sandstone layer cemented with opal. In the southwest corner of the state in Morton County rocks of Jurassic age outcrop along the Cimarron River. Loess deposits cover much of the High Plains in north and northwest Kansas.[18][19]

Glaciated Region

The northeast corner of the state, north of the Kansas River and east of the Big Blue River, is covered by glacial debris deposited during the Pre-Illinoian glaciations which occurred 600,000 years ago in the Pleistocene. The Pennsylvanian and Permian bedrock is buried under thick deposits of glacial debris, largely loess. A variety of glacial erratics were left by the melting glaciers. Many of these are of Sioux Quartzite carried south from the Sioux Falls, South Dakota area.[20]

Wellington-McPherson Lowlands

The Wellington-McPherson Lowlands of south-central Kansas in Sumner, Sedgwick, Harvey and McPherson counties is underlain by fluvial sediments deposited in the ancestral Arkansas River valley during the Pleistocene Epoch one to two million years ago. The sediments consist largely of sands, silts, and gravel. These include the Equus Beds Aquifer sediments, named for the Pleistocene modern horse fossils they contain. Also under this area is the Permian Hutchinson salt bed which reaches a thickness of 400 feet (120 m). The area also contains inactive sand dunes.[21]

Arkansas River Lowlands

The Arkansas River Lowlands follows the course of the Arkansas River through southwest and south-central Kansas. The broad floodplain contains large quantities of sand and silt carried from the Rocky Mountains by the river. A significant area of sand dunes occur on the south side of the plain formed by the prevailing winds from the glaciers to the north during the Pleistocene.[21]

Subsurface geology

The subsurface geology of Kansas consists of several sequences of sedimentary strata deposited on the Pre-Cambrian basement of the North American Craton.

Several regional subsurface structures including five sedimentary basins exist under Kansas. These structures are important in controlling the vast deposits of petroleum and natural gas in the state. The Central Kansas Uplift is a broad arch in the rocks of west-central Kansas. The rock units within this arch have been major oil producers. The Anadarko Basin of southwest Kansas contains significant natural gas. The Sedgwick Basin, the Cherokee Basin and the Forest City Basin of south and east Kansas also produce petroleum and natural gas.[22]

Proterozoic basement

The Nemaha uplift is a deep fault zone which runs diagonally across east Kansas and extends from just south of Omaha, Nebraska to Oklahoma City. This fault zone directly overlies a granite "high" in the Precambrian basement and is structurally active as the Humboldt Fault. Some fifty miles to the west the southernmost extension of the Proterozoic Midcontinent Rift System extends into northeastern Kansas.[23]

The northern two-thirds of Kansas is underlain by a Proterozoic sequence known as the Central Plains Orogen. The igneous and metamorphic rocks of this orogenic zone are considered to be an extension of the 1.7 Ga fold belt exposed in Colorado and Wyoming.[24] The southern approximately one-third of the state is underlain by the Southern granite-rhyolite province dating to 1.35 to 1.48 Ga.[24][25]

See also

- Wellington Formation, spanning Kansas to Oklahoma

References

- ^ Darton, Nelson Horatio. 1916. Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C - The Santa Fe Route, With a Side Trip to Grand Canyon of the Colorado. U.S. Geological Survey. Bulletin 613, 194 pp. (See Plate 3-A)

- ^ a b c d e f Buchanan, R., Kansas Geology: An Introduction to Landscapes, Rock, Minerals, and Fossils, University Press of Kansas, 1984, Ch 1, p. 10 ff ISBN 978-0700602407

- ^ Adams, George Irving. 1903. The physiographic divisions of Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 18:109-123.

- ^ "Physiographic Regions". Kansas Geological Survey (KGS) at University of Kansas (KU). Archived from the original on October 6, 2021.

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/ozark/ozark.html Ozark Plateau, KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/ozark/mining.html Archived July 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Lead and Zinc Mining, KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/cherokee/cherokee.html Cherokee Lowlands KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/cuestas/cuestas.html Archived 2009-02-24 at the Wayback Machine Osage Cuestas—Introduction, KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/cuestas/rocks.html Osage Cuestas—Rocks and Minerals, KGS

- ^ "Chautauqua Hills". Kansas Geological Survey (KGS) at University of Kansas (KU). Archived from the original on October 6, 2021.

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/flinthills/flinthills.html Archived February 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Flint Hills KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/flinthills/rocks.html Flint Hills—Rocks and Minerals KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/News/99_releases/kimberlites.html Rex Buchanan, Survey Discovers Three New Volcanic Features in Northeast Kansas, Kansas Geological Survey, October 29, 1999

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/redhills/redhills.html Red Hills KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/redhills/rocks.html Red Hills—Rocks and Minerals KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/smoky/smoky.html Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Smoky Hills KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/smoky/rocks.html Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Smoky Hills—Rocks and Minerals KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/highplains/highplains.html High Plains KGS

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/highplains/rocks.html High Plains—Rocks and Minerals

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/glacier/glacier.html Archived 2010-06-30 at the Wayback Machine Glaciated Region KGS

- ^ a b http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Extension/lowlands/lowlands.html Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Arkansas River Lowlands and Wellington-McPherson Lowlands

- ^ http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/Oil/primer09.html Petroleum geology of Kansas KGS

- ^ "Earthquakes in Kansas". Kansas Geological Survey. July 1996. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b P. K. Sims and Z. E. Petermar, Early Proterozoic Central Plains orogen: A major buried structure in the north-central United States, Geology 1986;14;488-491

- ^ Ben A. Van der Pluijm, Paul A. Catacosinos, Basement and basins of eastern North America, Geological Society of America, Special Paper 308, 1996, p. 14 ISBN 978-0-8137-2308-2