Central Troy Historic District

Central Troy Historic District | |

View west over downtown Troy from RPI, 2009 | |

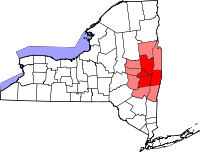

Interactive map showing Central Troy’s Historic District | |

| Location | Adams, 1st, 4th, Washington & Hill Sts., Franklin Pl., 5th Ave., Troy, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°43′39″N 73°41′27″W / 42.72750°N 73.69083°W |

| Area | 96 acres (39 ha) |

| Built | 1787-1940[1] |

| Architect | Various |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Victorian, Classical Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 86001527 (original) 16000367[2] (increase) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | August 13, 1986 |

| Boundary increase | June 14, 2016[2] |

The Central Troy Historic District is an irregularly shaped, 96-acre (39 ha) area of downtown Troy, New York, United States. It has been described as "one of the most perfectly preserved 19th-century downtowns in the [country]"[3] with nearly 700 properties in a variety of architectural styles from the early 19th to mid-20th centuries. These include most of Russell Sage College, one of two privately owned urban parks in New York, and two National Historic Landmarks. Visitors ranging from the Duke de la Rochefoucauld to Philip Johnson have praised aspects of it. Martin Scorsese used parts of downtown Troy as a stand-in for 19th-century Manhattan in The Age of Innocence.[4]

In 1986, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), superseding five smaller historic districts that had been listed on the Register in the early 1970s.[5] (Two years later, in 1988, the extension of the previous River Street Historic District north of Federal Street was added separately to the NRHP as the Northern River Street Historic District.) In late 2014, the State Historic Preservation Board began considering an adjustment to the district's boundaries that would be a net expansion, particularly in its southeast;[6] that increase was made official in 2016.[2] Most of the buildings, structures and objects within the district contribute to its historic character. Two of Troy's four National Historic Landmarks, the Gurley Building and Troy Savings Bank, are located within its boundaries. Nine other buildings are listed on the Register in their own right. Among the architects represented are Alexander Jackson Davis, George B. Post, Calvert Vaux and Frederick Clarke Withers. There are many buildings designed by the regionally significant architect Marcus F. Cummings. The downtown street plan was borrowed from Philadelphia, and one neighborhood, Washington Square, was influenced by London's squares of its era.

The district reflects Troy's evolution from its origins as a Hudson River port into an early industrial center built around textile manufacture and steelmaking. During this period it was rebuilt twice in the wake of two devastating fires, resulting in its mix of architecture styles. After the decline of its industries in the mid-20th century, downtown Troy was threatened by urban renewal efforts that galvanized local preservationists, leading to the early NRHP listings and eventually the creation of the district.

Today, the city of Troy protects and preserves the district with special provisions in its zoning and programs which, with assistance from the state of New York, encourage and subsidize property owners who maintain and restore historic buildings. These efforts have paid off with increased attention from developers, the revival of much of the area, and praise from visitors to the city. With the collaboration of nearby Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Troy is hoping to make the district a center for the development of cutting-edge technologies, a "Silicon Valley of the 19th century."[7]

Geography

The district boundary was drawn to include the highest concentration of historic resources. The street plan dates to 1787 and the most recent historic building dates to 1940, making those years the period of significance. While some newer buildings are inevitably located within the area, the boundary, where possible, excluded significant mid and late 20th-century buildings like the city hall, low-income housing projects, and the Uncle Sam Atrium, a large shopping mall downtown. All of the original five historic districts are included in full, along with other historic neighborhoods,[5] for a total of 10% of the city's area.[8]

Current (single) district

Original districts

It is centered around the axes of US 4 and NY 2, both of which divide into one-way streets (Third and Fourth, and Congress and Ferry, respectively) to facilitate traffic flow through the city. Monument Square, the center of Troy since the late 19th century, along with all the buildings around it (save for the late 20th-century brutalist City Hall, demolished in 2011[9]) are located within its northwestern corner. At its western end it is partially bounded by the Hudson River and the former River Street Historic District.[10]

To the south it includes the older buildings of Russell Sage College, Washington Square Park and the houses on Adams Street, the district's southern boundary. The mostly regular southeastern boundary follows Clinton Street until it reaches Ferry. Then it becomes ragged and irregular, reaching the district's northernmost extent at the former Grand Street Historic District. This extension allows it to include as well the Gurley Building and its surrounding neighborhood, formerly the Fifth Street-Fulton Street Historic District.[10]

To the east of the district Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Troy's most notable institution of higher learning, is situated on a low rise overlooking downtown. RPI has played an increasing role in the district in recent years, and now owns several notable buildings.

The entire district is densely developed, primarily residential in its northern and southern portions, with commercial use concentrated in central blocks near Monument Square. The only significant open spaces within it are the one-block Washington Park near its southern end and Seminary Park, the main quad at Russell Sage. Most of the major streets and the central area of the district are lined with multi-story dwellings that are primarily commercial but with a mix of office and residential space on their upper floors. On the side streets, there are smaller-scale residential townhouses. Institutional use is limited to Russell Sage, a few churches, RPI's buildings and governmental structures like the county courthouse and post office. No industrial use, past or present, is within the district, with the notable exception of the Gurley Building, and even that has been scaled back in recent years.

2016 expansion

In 2014 the State Historic Preservation Board considered a boundary adjustment that removes a small area at the northeast corner but adds far more, primarily at the southeast. It would include a total of 200 new contributing properties and extend the district's period of significance to 1978, to take into account the city's urban renewal era. Most of the new areas had been found to be consistent with those already included in the district or accidentally excluded when the district was originally designated.[11] Two years later the National Park Service officially approved the expansion.[2]

The most significant change to the district is the extension on the southeast, to the boundary of the city's Eighth Ward in 1870. Between Adams and Ferry streets, three blocks would be added, with the new boundary following the west side of St. Mary's Avenue, excluding a newer house at the northwest corner of the Washington Avenue intersection, and then rear property lines to Kennedy Lane and Hill Street just south of Adams.[12] Two-story rowhouses predominate in this area, many built as worker housing during the 19th century, some as early as the Federal period. Some have intact storefronts. It also has the only significant industrial building in the proposed expanded district, the former Lusco Paper Works on the northwest corner of Fifth and Liberty streets. The area has begun to see some restoration efforts, such as some Greek Revival rowhouses on Liberty Street near Fourth, which will benefit from state tax credits should the area be added to the district.[11]

On the west side the boundary would be extended a block, from First to River Street at the Congress Street Bridge approaches, between Division and Ferry streets.[12] This includes a large brick dorm complex built by Russell Sage College (RSC) in the early 1960s. It was the college's last large-scale construction project in the city; with its inclusion all of RSC would be within the district. To its south another proposed extension reaches across a small park on First to include the 1905 Beth Tephilah synagogue, a neoclassical brick structure that retains most of its integrity.[11]

Two other changes take in other significant buildings. Along the north side of Ferry at the district's east, just north of the Eighth Ward addition, the boundary would be extended east, taking in another set of rowhouses on the west side of Fifth and the city's former jail and sheriff's office at the northeast corner of Ferry and Fifth. On the north, the Uncle Sam Atrium shopping mall and parking garage complex, occupying most of the block between Broadway and Third, Fourth and Fulton streets would now be included.[12] Built in 1978, it is the only significant example of modern architecture in the district and the last large-scale project built in downtown Troy.[11]

Other, smaller areas proposed for inclusion are a group of brick houses, some of them blighted, along the south side of Washington Street between First Street Alley and River; a rowhouse and community garden on the corners of Adams Street and Second Street Alley; and another group of rowhouses along the west side of Fifth Street between State and Congress Streets.[12] The only areas proposed for removal are large portions of the blocks on the west side of Sixth Avenue on either side of Fulton. At the time the district was established, they were occupied by large industrial buildings, both of which were later demolished and replaced by parking lots.[11]

History

The history of the Central Troy Historic District is, particularly in its earlier years, the history of Troy itself. Until the later 19th century, the present downtown area was the city. Two devastating fires, along with changes in the economy brought about by industrialization, shaped the district into today's architecturally diverse downtown.

Pre-industrial years

Prior to independence, there had only been a few scattered Dutch farmers settled on the Hudson above Albany. In 1787, a group of New Englanders headed west and persuaded one Jacob Vanderhyden to sell them a large tract which they then subdivided and named Troy.[13] The dividing line between two of the family's farms was called Grand Division Street, later shortened to Grand Street.[14]

They based its grid-like street plan on Philadelphia's, with numbered north-south streets running inland from the river after River Street, the city's first commercial center.[13] Lots there, at the time, ran all the way to the river's waterline, giving their owners the unusual advantage of river and street frontage. The sloping bluff also allowed them to build multi-story warehouses and granaries closer to the unloading points along the river.[15]

In 1793, the new settlement was designated the Rensselaer County seat. Two years later, the visiting Duke de la Rochefoucauld noted the "neat and numerous houses" and active businesses engaged in river-based trade. "The sight of this activity is truly charming", he said, in one of the earliest published descriptions of the city. In 1798 Troy incorporated as a village.[16]

The village's population more than tripled in the first 15 years of the new century, leading it to reincorporate as a city in 1816.[17] With River Street getting built out, banks began taking advantage of the street plan and locating on First Street, previously a residential area. By 1807, another visitor from abroad, British painter John Lambert, described a town that had already grown considerably from what de la Rochefoucauld saw a dozen years earlier:

Troy is a well built town, consisting chiefly of one street of handsome red brick houses... There are two or three short streets which branch off from the main one, but it is in the latter that all of the principal stores, warehouses and shops are situated. It also contains several excellent inns and taverns. The houses are all new and lofty and built with much taste and simplicity, though convenience and accommodation seem to have guided the architect more than ornament. The deep red bricks, well pointed, give the buildings an air of neatness and cleanliness seldom met in old towns.[18]

Little of that Troy remains due to an 1820 fire which started in a First Street stable and eventually consumed much of the extant village. A column at 225 River Street bears a stone indicating that this was where the fire was stopped after it had gone on for weeks.[19] Unlike its classical namesake, Troy rebuilt quickly, with newer brick homes and commercial buildings, built to stricter standards, replacing the old ones and expanding again.[17] The Hart-Cluett Mansion, an 1827 Federal style house on Second Street, is one of the best surviving buildings from this era. Although it was previously attributed to Philip Hooker, new research has determined that the house's architect was Martin Euclid Thompson and the builder was John Bard Colegrove.[17][20]

Industrialization and growth

In 1824, a gazetteer of the state echoed earlier accounts in calling River Street "the mart of business".[21] The same year, RPI was founded on the hill to the east of downtown, to train engineers for the city's burgeoning industrial sector.[22] The relationship between the city and university would later become significant in preserving the historic district.

This growth would continue due to transportation improvements in the 1820s. Troy's businessmen had already built a turnpike to Schenectady, the path followed today by Route 2 from Troy to Colonie.[23] These trade routes were enhanced by the Erie and Champlain canals,[24] which opened new markets to the north and west, while the Troy Steamboat Company's debut did likewise for the south. The access to iron ore mines in the Adirondack Mountains also got some local businessmen into iron refining. In 1835 the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad brought that technology to the city, and in 1842 the completion of the Schenectady and Troy Railroad linked Troy to the vast network that reached as far west as Buffalo.[22]

The stage was set for Troy's industrialization. The development of the detachable collar by Hannah Lord Montague in 1827 had given the city the product that still lends it its "Collar City" nickname.[25] Plants were built to manufacture them commercially, as well as cuffs and other textile products. Most of these were located to the north of the downtown area, as it was continuing to grow as the city's commercial district and residential area for the well-to-do of the time along Second Street.[26]

With the newer money and newer neighborhoods came newer architectural trends. St. Paul's Episcopal Church, built in 1827, is an early Gothic Revival church, based on Ithiel Town's Trinity Church in New Haven, Connecticut. Eight years later, Town himself would design the Cannon Building in collaboration with Alexander Jackson Davis.[27]

Greek Revival residences were first built in Troy along Second Street in the late 1820s. In 1839, six local businessmen bought a parcel of land between Second and Third at the south end of what was then the developed area of the city and created Washington Park. Modeled on contemporary British residential squares such as those found in London's Bloomsbury neighborhoods,[28] its first phase, on Washington Place, featured rows of townhouses with a unified facade fronting on a park reserved exclusively for residents, whose deeds require a monthly maintenance fee. It retains its integrity despite some later alterations and damage and is one of only two privately owned urban parks in New York.[29][30][31]

In 1843, another group of planned Greek Revival townhouses was built at 160-168 Second Street. Unusual for urban houses, they featured one-and-a-half-story porticos on their front facades, with Ionic columns, and (originally) side yards. Another house was built at 170, several years later, in a similar style. They were widely imitated elsewhere in the city.[30]

The city's industries reached their peak in the 1850s, and the wealth it created explored new architectural trends. The emerging Italianate style began to make its mark, particularly in commercial buildings around Monument Square and along "Bankers' Row", First between State and River. St. Paul's Place was built around 1850 on the south side of State between Fourth and Fifth. Following the dictates of the Washington Park-area deeds, the houses were built with a unified facade as well as a central parapet. The Uri Gilbert Mansion on Second Street west of Washington Park is the most significant detached Italianate home from that era.[29][32]

Russell Sage built a row of Gothic Revival houses on Second Street in 1846 that survives, albeit without some of their original ornamentation. On the edges of town, some architects began exploring that style's Picturesque mode. A new row of townhouses at Washington Park went up, and another Second Street row followed in 1855. The following year, St. John's Episcopal Church, at First and Liberty Streets, was the first use of that style for a city church.[27]

During the Civil War, Troy's industries played a key role in supporting the Union cause. The Burden Ironworks is said to have supplied all the Union Army's horseshoes, and another local ironworks supplied the USS Monitor's hull plating. Its owners would later produce the first Bessemer process steel in the United States after the war.[32]

In 1862 Troy suffered another major fire, the worst in its history. A locomotive's spark ignited the wooden Green Island drawbridge that existed at the time, and when that could not be contained to the bridge it spread to the east, ultimately devastating 507 buildings over a 16-block area. As before, the city rebuilt quickly, with the area along Fifth between Broadway and Grant Street, where Cummings built a row of houses between Fifth and Sixth, most strongly reflecting this era of rapid construction and reconstruction. The Gurley Building, too, rose in just eight months from the ashes of its predecessor.[33] The nearby neighborhood also became desirable, with many local businessmen moving into newly built homes along Fifth.[34]

Postwar prosperity

As the postwar years yielded to the Gilded Age, Troy's prosperity continued. The wealth created by its industries built some of the city's most notable Victorian buildings. Frederick Clarke Withers designed First Street's Rice Building in 1871, a five-story flatiron-shaped building representative of his Victorian Gothic style.[35] The Cannon Building got a contemporary mansard roof after two fires. Cummings' 1870 Congregation Berith Sholom Temple on Third Street is among the oldest synagogue buildings still standing in the United States,[36] the oldest Reform synagogue in New York, and one of the most significant religious buildings in the district from this period. In 1875, George B. Post won a competition to build a new home for the Troy Savings Bank, with an upstairs auditorium. While his building was in the Renaissance Revival style of the time, its forms and decorations anticipated his later work in the Beaux-Arts vein.[37][38]

The Panic of 1873 put a damper on this growth, and in the interim the city's steel industry began to decline, squeezed by competition from newer, more efficient producers in Western Pennsylvania and the Midwest on one side and labor unrest at home. But the textile industry remained strong, and even grew. Accordingly, its residents continued to embrace new movements in architecture. The 1880 pharmacy building at 137 Second Street featured a highly decorated cast iron storefront and curved windows showing the influence of the Queen Anne Style. Further down Second Street, industrialist Jonas Heartt's house built that same year is one of the best residential applications of the same style.[39]

Cummings explored the Richardsonian Romanesque mode in several of his buildings at Russell Sage. The Paine Mansion at 49 Second Street applied the same style, with arcaded entrance loggia and corner tower, to a home. The brick drugstore annex at 155-157 River Street is a particularly representative commercial example of the style.[40] In 1893 the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago popularized the Classical and Renaissance revivals and Beaux-Arts style. They came to Troy very quickly when Marcus Cummings and his son Frederick designed the Classical Revival county courthouse at 80 Second Street, the third to occupy the site, the following year. A short distance away three years later, the Renaissance Revival Hart Memorial Library was built of Vermont marble, joining the similarly styled 1895 Frear Mansion, also on Second Street.[41]

As the 20th century dawned, builders and architects concentrated their efforts in the northern half of the district, primarily on commercial structures as the downtown area was no longer popular as a place for new residences. Monument Square, created in 1891 when a statue of Columbia was erected atop the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in the triangular area formed by the intersection of Broadway, River and Second streets, became a new focal point of development.[41] There the McCarthy Building on Monument Square, and the similar National State Bank and Ilium buildings on Broadway, all built in 1904, show the decorative influence of the era's revival styles.[42][43][44][45] Proctor's Theater, ten years later on Fourth Street, continued the tradition.[1][46]

Other architects chose the era's simpler styles, like Arts and Crafts, as a contrast. The marble-and-brick 1905 YMCA building on Second Street, and the six-story Caldwell Apartments at State and Second streets are two of the district's best examples of that style. The latter building, built in 1907, was also the first large-scale apartment building in the city.[47] The Colonial Revival style would also leave its mark in Troy with several buildings. Most notable among them is the Hendrick Hudson Hotel on the east side of Monument Square, a six-story structure that was the largest building ever built in the city at the time.[48] Projects of similar scale, and the city's annexation of the village of Lansingburgh to its north, helped swell its population to over 72,000 in 1930, its alltime peak.

Depression and decline

New construction almost halted when the Great Depression began in the 1930s. As a result, there are few buildings in the district in that era's architectural styles. The post office at Fourth and Broadway, built despite much public outcry over the demolition of its landmark 1894 predecessor,[49] is the district's most notable building of the 1930s. Its stripped-down Classical Revival style shows the influence of Art Deco in its smooth, finished surfaces. The enameled metal facade on a Third Street storefront, dating to 1940, makes it the only building in the district to show any trace of the Streamline Moderne style.[50]

World War II sustained the city's economy with an increased demand for textiles and all other products it could make. After the war ended, the textile mills, faced with competition from producers in the lower-wage South, closed or left.[51]

After a brief postwar increase, Troy's population began a continuing decline. The city began the first of several urban renewal plans shortly after adopting its 1962 master plan. Those plans called for the demolition of many buildings downtown, to be replaced by a new arterial road, large public housing projects and a shopping mall. After various delays, those projects were either scaled back or abandoned entirely. In the interim many businesses either closed or moved out of downtown.[51][52]

Preservation and renewal

In the late 1960s, public opposition to the planned demolition of some of the historic structures downtown like the McCarthy Building[53] led to them being placed on the then-new National Register. In the early 1970s, the five predecessor historic districts were recognized and added as well, along with some other structures.[5]

Urban renewal programs are funded in part by federal grants. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which created the NRHP, requires that federal agencies give consideration to the opinions of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation in assessing the impact their actions will have on listed properties and consider alternatives to any action that would destroy or significantly affect them. The listings of downtown Troy's districts and buildings therefore had the practical effect of preventing their demolition for urban renewal.[54]

By the 1980s, after a Troy Downtown Historic District had been declared eligible for the NRHP by the state's Historic Preservation Office but not yet submitted to the National Park Service (NPS), which administers the Register, local preservationists realized that the existing historic districts did not fully embrace all of downtown's historic properties. Instead of applying for boundary increases or nominating more individual properties to the Register, the city decided to merge all five into a new, central district.[5] The NPS accepted the application and entered the new district on the Register in 1986.[55]

Troy's downtown began reviving. In 1993, Martin Scorsese used the Second Street area, particularly the Paine Mansion, and some of the Russell Sage buildings as locations for his adaptation of Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence, since they replicated the appearance of 1870s Manhattan.[4] River Street became home to many antique stores.[3] Developers began buying the old buildings and adapting them to contemporary uses.[7] RPI began buying properties such as the Rice and Gurley buildings, moving students and faculty into them.[56] In 2006, The New York Times described the city as having "one of the most perfectly preserved 19th-century downtowns in the United States."[3] The district's success led to the proposed expansion in 2014.[6]

Significant contributing properties

The district includes all the area of the original five districts, two National Historic Landmarks, nine properties listed on the National Register in their own right, and several other noteworthy contributing properties among its 679 total historic resources.[1]

Predecessor districts

- Fifth Street-Fulton Street Historic District. Many of the city's then-prominent businessmen built townhouses here, near the Gurley Building, after the 1862 fire.[34]

- Grand Street Historic District: Marcus Cummings built townhouses here after that fire.[14]

- River Street Historic District: The city's antique district is the oldest neighborhood in Troy, and its pre-industrial commercial center.[15]

- Second Street Historic District: Many unaltered homes dating to the 1820s, some of them owned by prominent city residents, in the vicinity of the Troy Savings Bank building.[57]

- Washington Park Historic District: Local businessmen started the city's first planned neighborhood in 1839, the first large Greek Revival development in the city. They used London's residential squares as their model. Philip Johnson called it "one of the finest squares in North America".[28]

National Historic Landmarks

- W. & L.E. Gurley Building: Fifth and Fulton streets. Built in just nine months after 1862 fire, this location has been home to Gurley Precision Instruments since 1845. The building, with Renaissance and classically inspired stylings, is an unusual example of a commercial building extremely sympathetic to its neighboring residences.[58] Today owned by RPI and home to some of its divisions, including the Lighting Research Center.[59]

- Troy Savings Bank: 32 Second Street. Designed by George B. Post in 1875 in stylings that anticipate the emergence of Beaux-Arts,[37][38] this impressive stone building features a full concert hall upstairs with excellent acoustics.[60]

National Register of Historic Places

- Cannon Building: 1-9 Broadway, on the south side of Monument Square. This 1835 collaboration by Alexander Jackson Davis and Ithiel Town got a mansard roof after an 1870 fire.[37] Today it is used as an extended-stay hotel and office space.[61]

- Hart-Cluett Mansion: An 1828 Federal mansion on Second Street built by a New York merchant as a wedding gift to his daughter. Largely unchanged, it is today the home of the Rensselaer County Historical Society.[20]

- Ilium Building: Marcus Cummings designed this commercial building at Fourth and Fulton in 1904.[44]

- McCarthy Building: 255 River Street, on the west side of Monument Square. Another 1904 building, noted for large proscenium-style front arch window from original use as furniture showroom.[42] Today it hosts the Troy offices of a regional media company.[53]

- National State Bank Building: 297 River Street. Its fenestration and decoration is similar to Cummings' Ilium Building a block away.[43]

- Proctor's Theater: A 1914 theater on Fourth Street transitioned smoothly between live-entertainment and motion-picture eras.[46] RPI had hoped to convert it into a hotel,[62] but a new proposal to gut the interior completely has been the subject of local controversy.[63]

- St. Paul's Episcopal Church: State and Third streets. This 1828 stone Gothic Revival structure is an almost exact duplicate of Ithiel Town's Trinity Church in New Haven, Connecticut.[64]

- Troy Public Library: 100 Second Street. It is an 1897 white marble building that has been described as "one of the finest works of Italian Renaissance architecture in the country".[65]

- U.S. Post Office: Fourth and Broadway. Built in 1936, it is one of the most modern of the contributing properties in the district, using a stripped Classical Revival style for the tenth post office location in the city's history. Its lobby contains one of only three Waldo Peirce murals in American post offices.[49]

Other notable contributing properties

- Commercial building at 46 Third Street: Downtown Troy's only example of Streamline Moderne architecture. Having an enameled metal facade and storefront, and dating to 1940, it is the newest contributing property in the district.[50]

- Caldwell Apartments: Second and State streets. This Arts and Crafts-style building from 1907 was Troy's first large-scale apartment building.[50]

- The Conservatory of Troy: 65 Third Street built in 1903 for the Dodge Dry Goods Co was Troy’s first skyscraper. Built by the same firm that constructed the famous Flatiron Building in Manhattan.

- Congregation Berith Sholom Temple: 167 Third Street. The oldest Reform synagogue in New York, and one of the oldest surviving synagogues in the country; built in 1870 by Cummings.[37]

- Hendrick Hudson Hotel: Located on the east side of Monument Square. This seven-story brick Colonial Revival building, dating to 1932, is the largest building on the square.[48]

- House at 18 First Street The oldest house in the district is this Federal-style brick house, built in 1808 and added to in 1875, that survived the 1820 fire.[66]

- Julia Howard Bush Center: Originally First Presbyterian Church, on the Russell Sage campus in Seminary Park at First and Congress streets. A Greek Revival hexastyle temple-front church built in 1835, it is one of only ten remaining buildings in that style in the U.S.[8]

- Paine Mansion: 49 2nd Street. This limestone-faced Romanesque Revival home was built in 1894.[67]

- Rensselaer County Courthouse: 80 Second Street. The third courthouse on the site was built in 1894 by Cummings in the Classical Revival style. The neighboring Second Street Presbyterian Church, built in 1833, was later annexed to it and remodeled in 1913.[41]

- Rice Building: First and River streets. Calvert Vaux and Frederick Clarke Withers designed this Polychrome 1871 brick flatiron-shaped building. One of the district's rare examples of Victorian Gothic; formerly owned by RPI, the building is now owned by Tai Ventures and is home to several technology businesses.[35]

- St. John's Episcopal Church: First and Liberty streets. Henry Dudley designed this Stone Gothic Revival church built in 1856 by in the style of English parish churches that closely follows models of church design embraced by the contemporary Oxford Movement.[32]

- St. Paul's Place: Off State Street between Fourth and Fifth avenues. This is a street of six attached three-story brick rowhouses built ca. 1850. They feature a variation on Italianate norms with bracketed gables and rounded-arch windows and doors rarely seen with that style in an urban environment.[32]

- Thompson Drug Company Annex: 155-157 River Street. This five-story Richardsonian Romanesque brick building from 1888 copies one of Richardson's buildings in Pittsburgh.[15]

- Vail House: 46 First Street. This Federal-style 1818 home is the most notable structure to have survived the 1820 fire.[68]

Today

The city has recognized the historic district in its zoning code. It divides the area into six separate districts — the Riverfront, First, Second, Third, Fourth Street and Fifth Avenue local historic districts. The Riverfront district includes the neighborhood to the northwest listed on the National Register as the Northern River Street Historic District. The other five are roughly aligned with the eponymous streets, with the First Street district consisting of two detached areas, the Second and Third street districts taking up most of the central area and the other two occupying the northeastern corner of the district.[69] The city has also made some grants and tax exemptions available to qualified property owners.[70] The city's current master plan calls for enhancing the district's mixed-use character, by encouraging both residential use and businesses that serve consumers, particularly retailers, and providing tax incentives for the rehabilitation of historic homes.[71]

Troy's ordinances designate its Planning Commission as the Historic District and Landmarks Review Commission.[72] Property owners in the district must get special permission from the commission for any work on their properties beside ordinary maintenance (and even for that in some cases), to make sure it leaves the historic character of the property and the surrounding buildings intact.[73]

In 1989, the state added most of the district to Troy's Empire Zone.[74] This economic development incentive gives businesses that locate in the included areas tax credits and exemptions to encourage them to locate there.[75] The state has also moved some of its employees into the district, through the interventions of former State Senate majority leader Joseph Bruno, a resident of nearby Brunswick, who represented the district that included the city. He steered state grants towards the rehabilitation of the buildings that now house state government offices, as well as school aid that helped the city keep its property taxes low. City officials say his help has been vital and will be missed following his 2008 resignation.[7][76]

RPI has acquired several significant downtown properties, such as the Gurley and Rice buildings and Proctor's Theater,[62] and renovated them to make homes for programs such as its Lighting Research Center,[59] now housed in Gurley.[7] In the early 2000s, it put $2.5 million into its Neighborhood Renewal Initiative, which has been used to help homeowners renovate homes and improve the city's infrastructure.[77]

The private sector has also played a large role in revitalizing the area, even without public aid and incentives. Developers have been attracted to the historic buildings and their surrounding neighborhoods, calling it the city's strongest asset, although they have complained about past stalemates in city government. One initiative has often led to others. River Street's development into a center for antique stores came about without any public effort or intent, and the restoration of the music hall at the Savings Bank led to many new restaurants opening in the neighborhood.[7] The blocks of River Street north of Monument Square have a dozen woman-owned businesses.[78]

Developers, the city, and the colleges see downtown Troy's future as a center for high-tech companies and the good-paying jobs they provide. In addition to its historic character, the area has space available and is walkable. One local official calls Troy "the Silicon Valley of the 19th century".[7] Some specific projects have capitalized on this. In 2005, the Cannon Building was redeveloped into an extended-stay hotel with the target market being visiting faculty at RPI and Russell Sage.[61] With money from the 2009 federal stimulus package, the city improved traffic signals and sidewalks at 18 intersections downtown.[79]

The revitalization of downtown Troy has not been entirely without controversy over some of its historic buildings. A 2009 proposal to redevelop Proctor's by gutting its interior and converting it to office space led to serious opposition.[63] Opponents of the plan organized a website[80] and started an online petition against the use of any state funds for the project. Proponents, including the head of the city's Downtown Collaborative, said that after three decades of the vacant building's deterioration, any redevelopment proposal should be seriously considered, regardless of its impact on the building's historic character.[63][81]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Peckham, p. 2

- ^ a b c d "National Register of Historic Places announcements for June 24, 2016". U.S. National Park Service. June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bernstein, Fred (April 7, 2006). "Where the Finest Antiques Can't Be Bought". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Visit Troy". City of Troy. November 24, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

Our architecture is in high demand by Hollywood for movies set in the nineteenth century, with movies such as "The Age of Innocence" and "Time Machine" having been filmed here.

- ^ a b c d Peckham, p. 3

- ^ a b LaFrank, Kathleen (October 2014). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Central Troy Historic District (Boundary Expansion)" (PDF). New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Brien, Tim (Spring 2004). "Reinventing Troy". Rensselaer. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 11

- ^ Crowe, Kenneth (January 26, 2011). "State cites Troy over City Hall demolition". Albany Times-Union. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Peckham, pp. 4–5, 155

- ^ a b c d e LaFrank, 5–8

- ^ a b c d LaFrank, 60

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 138

- ^ a b Waite, Diana (March 1972). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Grand Street Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

Formerly called Grand Division Street, the thoroughfare once formed the boundary between the northern and middle farms of Dirk Van der Hyden, one of the earliest settlers of the Troy area.

- ^ a b c Vanderlipp-Manley, Doris. "National Register of Historic Places nomination, River Street Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ^ Weise, Arthur James; Troy's One Hundred Years; William H. Brown, Troy, New York; 1891; 44, cited at Peckham, p. 138

- ^ a b c Peckham, p. 140

- ^ Weise, cited at Peckham, p. 139

- ^ Vanderlipp-Manley, River Street, 6. "The disaster is recalled by an inscription carved into the northernmost column of No. 225: 'The destructive fire of 20 June 1820 arrested at this point.'"

- ^ a b Brooke, Cornelia (September 1971). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Hart-Cluett Mansion". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ Cited at Vanderlipp-Manley, 5.

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 141

- ^ George Rogers Howell (1886). History of the County of Schenectady, N.Y., from 1662 to 1886. W.W. Munsell and Co. Publishers.

- ^ Peckham, pp. 140–41 "Beginning in 1825, Troy's natural transportation advantage at the head of practical river navigation was amplified by the completion of the Erie and Champlain canals, connected to Troy by way of the Watervliet Side Cut."

- ^ Rittner, Don. "The Collar City". Troy Record. rootsweb.com. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

Mrs. Montague, tired of washing her husband's shirts because only the collars were dirty, decided one day to snip off a collar, wash it, and sew it back on. Mr. Montague, it's written, agreed to the experiment, and in 1827, the first detachable collar was made at their home ... By the early 20th century, 15,000 people worked in the collar industry in Troy, and more than 85% were native-born women. Ninety out of every 100 collars worn in America were made here, and Troy became world famous as the 'Collar City.'

- ^ Peckham, pp. 142–44

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 142

- ^ a b Waite, Diana (April 1973). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Washington Park Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 14

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 143

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (July 7, 1998). "The Other Washington Park Continues to Flower With Pride". Albany Times-Union. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

Washington Park in Troy is one of only two private residential urban parks in New York state

[permanent dead link] - ^ a b c d Peckham, p. 145

- ^ Peckham, p. 146

- ^ a b Waite, Diana (December 1969). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Fifth Avenue-Fulton Avenue Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 28. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Peckham, pp. 146–47

- ^ Gordon, Mark (1996). "Rediscovering Jewish Infrastructure: Update on United States Nineteenth Century Synagogues". American Jewish History. 84 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1353/ajh.1996.0013. JSTOR 23885494. S2CID 162276183. Project MUSE 379 ProQuest 1296121382.

- ^ a b c d Peckham, p. 147

- ^ a b Pitt, Carolyn; National Register of Historic Places nomination, Troy Savings Bank, undated, retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Peckham, p. 148 "Infill residential construction on some of Troy's older streets also illustrates the [Queen Anne] style. One of the best examples in the historic district is the Jonas Heartt house at 169 Second Street in Washington Park."

- ^ Peckham, p. 149

- ^ a b c Peckham, p. 150

- ^ a b Waite, Diana (December 1969). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, McCarthy Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Liebs, Chester (May 1970). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, National State Bank Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Liebs, Chester (May 1970). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Ilium Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ^ Peckham, p. 151

- ^ a b Powers, Robert (May 1979). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Proctor's Theater". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- ^ Peckham, pp. 151–52

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 152

- ^ a b Gobrecht, Larry (December 1986). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, U.S. Post Office-Troy". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c Peckham, pp. 152–53

- ^ a b Peckham, p. 153

- ^ "Summary of the City of Troy's South Troy Working Waterfront". River Street Planning & Development LLC. September 15, 1999. p. 5. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ^ a b DerGurahian, Jean (April 21, 2000). "Media firm to call Troy's McCarthy building home". Albany Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Retrieved November 8, 2008.

- ^ "Information for Owners". State Historical Society of Iowa. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

National Register status does not mean that a property cannot be destroyed by a highway, by Urban Renewal, or some other project. It does mean that before a federal agency can be involved in any way with such a project, i.e. by funding, licensing or authorizing it, the federal agency must consider alternatives by which National Register properties might be saved from destruction.

- ^ "NEW YORK - Rensselaer County - Historic Districts". nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ "Rensselaer Announces Purchase of Proctor's Theatre Building in Downtown Troy" (Press release). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. April 6, 2004. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

The purchase of the Proctor's Theatre building is part of Rensselaer's ongoing 'communiversity' efforts toward the revitalization under way in the City of Troy. Over the last five years Rensselaer has moved faculty, staff, and students into offices, research facilities, and incubator space in the Hedley Building, Gurley Building, and Rice Building, all in downtown Troy.

- ^ Waite, Diana (July 1974). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Second Street Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ George R. Adams (November 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: W. & L.E. Gurley Building" (pdf). National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Visit Us". Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

The LRC is located in the historic Gurley Building in downtown Troy, New York.

- ^ McClintock, R. (2008). "The Hall Acoustics". Troy Savings Bank Music Hall. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

The debate still rages over whether George Post planned the Troy Savings Bank Music Hall to be the acoustical marvel it is.

- ^ a b Wood, Robin (January 11, 2005). "Luxury extended-stay apartments set to open in Troy". Albany Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

The renovated Cannon Building on Broadway in Troy, N.Y., is offering 10 of the building's 30 apartments for short-term rentals

- ^ a b "Rensselaer Announces Purchase of Proctor's Theatre Building in Downtown Troy" (Press release). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. April 6, 2004. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

The goal is to develop a high-end hotel that will provide economic and community benefits to the city of Troy and to the surrounding area

- ^ a b c Caprood, Tom (April 23, 2009). "A discussion about Proctor's". The Record. Journal Register Company. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- ^ Dunn, Shirley (June 19, 1979). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, St. Paul's Episcopal Church (JavaScript)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2008.

- ^ Waite, Diana (July 1972). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Troy Public Library". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Peckham, p. 35

- ^ Peckham, p. 9

- ^ Peckham, pp. 139–40 "... [S]everal examples of the house type described by Lambert and built before 1820 remain on First Street and serve to illustrate Troy's early nineteenth century architecture. Foremost among these is the Federal style Vail House at 46 First Street, built in 1818".

- ^ "Historic District Map 2004" (PDF). City of Troy Planning Department. June 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ "Troy NY Economic Development". City of Troy. 2006. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "City of Troy, NY, 5-Year CP Strategic Plan 2005-2009, Executive Summary (Updated)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2008., April 28, 2005; retrieved November 26, 2008; 4-6.

- ^ "E-Code Library; General Code; ordinance codification; document management; municipal codes online; Internet codes; ordinances". www.generalcode.com. Retrieved November 26, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Troy's Historic District". City of Troy. 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Empire Zone — Yearly Designations (PDF) (Map). 1:36,000. City of Troy. 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Troy NY Empire Zone Program". City of Troy. 2006. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Confessore, Nicholas (June 27, 2008). "The Sad, Proud Elegies Start in Bruno's District". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

[Troy Mayor] Harry Tutunjian and many others credit Mr. Bruno for rescuing Troy from the brink of insolvency during the mid-1990s, winning financing from a program for distressed cities and directing school aid to the area to enable Troy to keep property taxes low. Nearly every nonprofit organization in the city has received one grant or another from Mr. Bruno over the years, as have at least a dozen or so businesses.

'People won't realize how important he was until years from now, when they find that things don't get done as quickly or as easily without him,' Mr. Tutunjian said. - ^ Ackerman, Jodi (September 2002). "Good Neighbors". Rensselaer. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Anderson, Eric (July 25, 2008). "A Troy tradition: businesswomen". Albany Times-Union. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved June 28, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Project Narrative and CDBG-R Eligibility Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2009., U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ "Save Proctor's Theater!". 2009. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Young, Elizabeth (April 8, 2009). "The Drama Over Troy's Theatre". Albany Times-Union. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

32 years is a long time. 32 years vacant. 32 years of a block of Downtown Troy that I would not walk down alone after dark. 32 years of similar preservation efforts that have blossomed, and then withered. 32 years of potential, left unfulfilled. I am 31 years old - this building has been vacant for my entire lifetime.

Bibliography

- Peckham, Mark (July 1986). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Central Troy Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation (NYSOPRHP). Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2010. Also see excerpts at "Central Troy Historic District".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

External links

All of the following are located in Troy, Rensselaer County, NY:

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-5-A-3, "Albert Cluett House, 59 Second Street", 2 photos, 8 measured drawings, 2 data pages

- HABS No. NY-5-A-7, "Thomas Samuel Vail House, 46 First Street", 4 photos, 12 measured drawings, 2 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. NY-358, "St. John's Rectory (Balcony), First & Liberty Streets", 1 photo, 1 measured drawing, 2 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. NY-3239, "Gothic Revival House", 1 photo

- HABS No. NY-6257, "Church of the Holy Cross, Eighth & Grand Streets", 11 photos, 2 measured drawings, 8 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HABS No. NY-6380, "204 Washington Street, 204 Washington Street", 2 data pages

- HABS No. NY-6381, "177-179 Second Street, 177-179 Second Street", 2 data pages

- HABS No. NY-6382, "Godson Residence, 170 Second Street", 2 data pages

- HABS No. NY-6383, "Joseph B. Carr Building, 57 Second Street", 2 data pages

- HABS No. NY-6384, "Eddy Homestead, Eddy Lane", 2 data pages

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-2, "Troy Gas Light Company, Gasholder House, Jefferson Street & Fifth Avenue", 15 photos, 4 measured drawings, 12 data pages

- HAER No. NY-3, "Rensselaer Iron Works, Rail Mill, Adams Street & Hudson River", 18 photos, 4 measured drawings, 21 data pages

- HAER No. NY-13, "W. & L. E. Gurley Building, 514 Fulton Street", 6 photos, 11 data pages