Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini | |

|---|---|

Bust of Benvenuto Cellini on the Ponte Vecchio, Florence | |

| Born | 3 November 1500 |

| Died | 13 February 1571 (aged 70) Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany |

| Resting place | Santissima Annunziata, Florence[1] |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Accademia delle Arti del Disegno |

| Known for | Goldsmith, sculptor, author |

| Notable work | Cellini Salt Cellar |

| Movement | Mannerism |

Benvenuto Cellini (/ˌbɛnvəˈnjuːtoʊ tʃɪˈliːni, tʃɛˈ-/, Italian: [beɱveˈnuːto tʃelˈliːni]; 3 November 1500 – 13 February 1571) was an Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and author. His best-known extant works include the Cellini Salt Cellar, the sculpture of Perseus with the Head of Medusa, and his autobiography, which has been described as "one of the most important documents of the 16th century".[2][3]

Biography

Youth

Benvenuto Cellini was born in Florence, in present-day Italy. His parents were Giovanni Cellini and Maria Lisabetta Granacci. They were married for 18 years before the birth of their first child. Benvenuto was the second child of the family. The son of a musician and builder of musical instruments, Cellini was pushed towards music, but when he was fifteen, his father reluctantly agreed to apprentice him to a goldsmith, Antonio di Sandro, nicknamed Marcone. At the age of 16, Benvenuto had already attracted attention in Florence by taking part in an affray with youthful companions. He was banished for six months and lived in Siena, where he worked for a goldsmith named Fracastoro (unrelated to the Veronese polymath). From Siena he moved to Bologna, where he became a more accomplished cornett and flute player and made progress as a goldsmith.[4] After a visit to Pisa and two periods of living in Florence (where he was visited by the sculptor Torrigiano), he moved to Rome, at the age of nineteen.[5][6]

Work in Rome

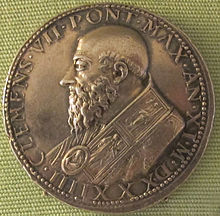

His first works in Rome were a silver casket, silver candlesticks, and a vase for the bishop of Salamanca, which won him the approval of Pope Clement VII. Another celebrated work from Rome is the gold medallion of "Leda and the Swan" executed for the Gonfaloniere Gabbriello Cesarino, and which is now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence.[7] He also took up the cornett again, and was appointed one of the pope's court musicians.[5][8]

In the attack on Rome by the imperial forces of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor under the command of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and Constable of France, Cellini's bravery proved of signal service to the pontiff. According to Cellini's own accounts, he shot and injured Philibert of Châlon, prince of Orange[9] (and, allegedly, shot and killed Charles III resulting in the Sack of Rome). His bravery led to a reconciliation with the Florentine magistrates,[10] and he soon returned to his hometown of Florence. Here he devoted himself to crafting medals, the more famous of which are "Hercules and the Nemean Lion", in gold repoussé work, and "Atlas supporting the Sphere", in chased gold, the latter eventually falling into the possession of Francis I of France.[11]

From Florence, he went to the court of the duke of Mantua, and then back to Florence. On returning to Rome, he was employed in the working of jewelry and in the execution of dies for private medals and for the papal mint.[12] In 1529, his brother Cecchino killed a Corporal of the Roman Watch and in turn was wounded by an arquebusier, later dying of his wound. Soon afterward Benvenuto killed his brother's killer—an act of blood revenge but not justice as Cellini admits that his brother's killer had acted in self-defense.[13] Cellini fled to Naples to shelter from the consequences of an affray with a notary, Ser Benedetto, whom he had wounded. Through the influence of several cardinals, Cellini obtained a pardon. He found favor with the new pope, Paul III, notwithstanding a fresh homicide during the interregnum three days after the death of Pope Clement VII in September 1534. The fourth victim was a rival goldsmith, Pompeo of Milan.[14]

Ferrara and France

The plots of Pier Luigi Farnese led to Cellini's retreat from Rome to Florence and Venice, where he was restored with greater honour than before. At the age of 37, upon returning from a visit to the French court, he was imprisoned on a charge (apparently false) of having embezzled the gems of the pope's tiara during the war. He was confined to the Castel Sant'Angelo, escaped, was recaptured, and was treated with great severity; he was in daily expectation of death on the scaffold. While imprisoned in 1539, Cellini was the target of an assassination attempt of murder by ingestion of diamond dust; the attempt failed, for a nondiamond gem was used instead.[15] The intercession of Pier Luigi's wife, and especially that of the Cardinal d'Este of Ferrara, eventually secured Cellini's release, in gratitude for which he gave d'Este a splendid cup.[12][16]

Cellini then worked at the court of Francis I at Fontainebleau and Paris. Cellini is known to have taken some of his female models as mistresses, having an illegitimate daughter in 1544 with one of them while living in France, whom he named Costanza.[17] Cellini considered the Duchesse d'Étampes to be set against him and refused to conciliate with the king's favorites. He could no longer silence his enemies by the sword, as he had silenced those in Rome.[12]

Final return to Florence and death

After several years of productive work in France, but beset by almost continual professional conflicts and violence, Cellini returned to Florence. There he once again took up his skills as a goldsmith, and was warmly welcomed by Duke Cosimo I de' Medici – who elevated him to the position of court sculptor and gave him an elegant house in Via del Rosario (where Cellini built a foundry), with an annual salary of two hundred scudi. Furthermore, Cosimo commissioned him to make two significant bronze sculptures: a bust of himself, and Perseus with the head of Medusa (which was to be placed in the Lanzi loggia in the centre of the city).

In 1548, Cellini was accused by a woman named Margherita of having committed sodomy with her son Vincenzo,[18] and he temporarily fled to seek shelter in Venice. This was neither the first nor the last time that Cellini was implicated for sodomy (once with a woman and at least three times with men during his life), illustrating his homosexual or bisexual tendencies.[19][20][21] For example, earlier in his life as a young man, he was sentenced to pay 12 staia of flour in 1523 for relations with another young man named Domenico di Ser Giuliano da Ripa.[22] Meanwhile, in Paris a former model and lover brought charges against him of using her "after the Italian fashion" (i.e., sodomy).[22]

During the war with Siena in 1554, Cellini was appointed to strengthen the defences of his native city, and, though rather shabbily treated by his ducal patrons, he continued to gain the admiration of his fellow citizens by the magnificent works which he produced.[12] According to Cellini's autobiography, it was during this period that his personal rivalry with the sculptor Baccio Bandinelli grew.[23] On 26 February 1556, Cellini's apprentice Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano accused his mentor of having sodomised him many times while "keeping him for five years in his bed as a wife".[24] This time the penalty was a hefty 50 golden scudi fine, and four years of prison, remitted to four years of house arrest thanks to the intercession of the Medicis.[22] In a public altercation before Duke Cosimo, Bandinelli had called out to him Sta cheto, soddomitaccio! (Shut up, you filthy sodomite!) Cellini described this as an "atrocious insult", and attempted to laugh it off.[25]

After briefly attempting a clerical career, in 1562 he married a servant, Piera Parigi, with whom he claimed he had five children, of whom only a son and two daughters survived him.

He was also named a member (Accademico) of the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno of Florence, founded by the Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, on 13 January 1563, under the influence of the architect Giorgio Vasari. He died in Florence on 13 February 1571 and was buried with great pomp in the church of the Santissima Annunziata.

Artwork

Statues

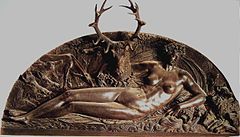

Besides his works in gold and silver, Cellini executed sculptures of a grander scale. One of the main projects of his French period is probably the Golden Gate for the Château de Fontainebleau. Only the bronze tympanum of this unfinished work, which represents the Nymph of Fontainebleau (Paris, Louvre), still exists, but the complete aspect can be known through archives, preparatory drawings and reduced casts.[26][27][28]

- 1542 Cellini statue which would have flanked the Nymphe de Fontainebleau

- The Nymph of Fontainebleau, by Benvenuto Cellini, now in the Louvre (1542)

- 1542 Cellini statue which would have flanked the Nymphe de Fontainebleau

Upon his return from France to his hometown Florence in 1545, Benvenuto cast a bronze bust of Cosimo I Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.[29] On this statue, Cellini crafted three anthropomorphic heads on to the armour of the duke. The first of them is "grotesque" situated on the right shoulder of Cosimo. The decorative head is composed of lineaments of a satyr, lion and a man. Two other heads, much smaller than the first and almost identical, can be found beneath the collarbones on the bust's front. His most distinguished sculpture is the bronze group of Perseus with the Head of Medusa, a work (first suggested by Duke Cosimo I de Medici) now in the Loggia dei Lanzi at Florence, his attempt to surpass Michelangelo's David and Donatello's Judith and Holofernes. The casting of this work caused Cellini much trouble and anxiety, but it was hailed as a masterpiece as soon as it was completed. The original relief from the foot of the pedestal—Perseus and Andromeda—is in the Bargello, and has been replaced by a cast.[12]

By 1996, centuries of environmental pollution exposure had streaked and banded the statue. In December 1996 it was removed from the Loggia and transferred to the Uffizi for cleaning and restoration. It was a slow process, and the restored statue was not returned to its home until June 2000.[citation needed]

Decorative art and portraiture

Among his art works, many of which have perished, were a colossal Mars for a fountain at Fontainebleau and the bronzes of the doorway, coins for the Papal and Florentine states, a life-sized silver Jupiter, and a bronze bust of Bindo Altoviti. The works of decorative art are florid in style.[12]

In addition to the bronze statue of Perseus and the medallions previously referred to, the works of art in existence today are a medallion of Clement VII commemorating the peace between the Christian princes, 1530, with a bust of the pope on the reverse and a figure of Peace setting fire to a heap of arms in front of the temple of Janus, signed with the artist's name; a signed portrait medal of Francis; a medal of Cardinal Pietro Bembo;[12] and the celebrated gold, enamel and ivory [citation needed] salt cellar (known as Saliera) made for Francis I of France at Vienna. This intricate 26-cm-high sculpture, of a value conservatively estimated at 58,000,000 schilling, was commissioned by Francis I. Its principal figures are a naked sea god and a woman, sitting opposite each other with legs entwined, symbolically representing the planet Earth. Saliera was stolen from the Kunsthistorisches Museum on 11 May 2003 by a thief who climbed scaffolding and smashed windows to enter the museum. The thief set off the alarms, but these were ignored as false, and the theft remained undiscovered until 8:20 am. On 21 January 2006 the Saliera was recovered by the Austrian police and later returned to the Kunsthistorisches Museum where it is now back on Kunstkammer display.[30] One of the more important works by Cellini from late in his career was a life-size nude crucifix carved from marble. Although originally intended to be placed over his tomb, this crucifix was sold to the Medici family who gave it to Spain. Today the crucifix is in the Escorial Monastery near Madrid, where it has usually been displayed in an altered form – the monastery added a loincloth and a crown of thorns. For detailed information about this work, see the text by Juan López Gajate in the Further Reading section of this article. Cellini, while employed at the papal mint at Rome during the papacy of Clement VII and later of Paul III, created the dies of several coins and medals, some of which still survive at this now-defunct mint. He was also in the service of Alessandro de Medici, first duke of Florence, for whom he made in 1535 a 40-soldi piece with a bust of the duke on one side and standing figures of the saints Cosima and Damian on the other. Some connoisseurs attribute to his hand several plaques, "Jupiter crushing the Giants," "Fight between Perseus and Phineus", a Dog, etc.[12] Other works, such as the portrait bust shown, are not directly attributed but are instead attributed to his workshop.

Lost works

The important works which have perished include the uncompleted chalice intended for Clement VII; a gold cover for a prayer book as a gift from Pope Paul III to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, both described at length in his autobiography; large silver statues of Jupiter, Vulcan and Mars, created for Francis I during his stay in Paris; a bust of Julius Caesar; and a silver cup for the cardinal of Ferrara. The magnificent gold "button", or morse (a clasp for a cape), made by Cellini for the cape of Clement VII, the competition for which is so graphically described in his autobiography, appears to have been sacrificed by Pope Pius VI, with many other priceless specimens of the goldsmith's art, in furnishing the 30 million francs demanded by Napoleon I at the conclusion of the campaign against the Papal States in 1797. According to the terms of the treaty, the pope was permitted to pay a third of that sum in plate and jewels. In the print room of the British Museum are three watercolour drawings of this splendid morse by F. Bertoli, done at the insistence of an Englishman named Talman in the first half of the 18th century. The obverse and reverse, as well as the rim, are drawn full size, and moreover the morse with the precious stones set therein, including a diamond then considered the second-largest in the world, is fully described.[12]

Drawings and sketches

The known drawings and sketches by Benvenuto Cellini are as follows:

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Bearded Man. Recto. 28.3 x 18.5 cm. Paper, graphite. (1540–1543) (?) Royal Library, Turin.[31]

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Study of a man, body and profile. Verso. 28.3 x18.5 cm. Paper, graphite (1540–1543) (?) Royal Library, Turin.[31]

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Paint Self-Portrait. 1558–1560. Oil, paper glued to canvas. 61 cm by 48 cm. Private collection

- Benvenuto. Juno. Drawing on paper. Cabinet of Drawings, Louvre Museum, Paris

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Satyr. 41 x 20.2 cm. Pen, ink. National Gallery of Art, Washington (from the Ian Woodner Collection, New York)

- Cellini, Benvenuto. A Study for the Seal of the Accademia del Disegno. 30 x 12.5 cm. Pen, brown ink. Louvre, Paris

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Mourning Woman. 30 x 12.5 cm. Pen, brown ink. Louvre Museum, Paris

In literature, music and film

Autobiography

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini was started in the year 1558 at the age of 58 and ended abruptly just before his last trip to Pisa around the year 1563 when Cellini was approximately 63 years old. The memoirs give a detailed account of his singular career, as well as his loves, hatreds, passions,[21] and delights, written in an energetic, direct, and racy style; as one critic wrote, "Other goldsmiths have done finer work, but Benvenuto Cellini is the author of the most delightful autobiography ever written."[32] Cellini's writing shows a great self-regard and self-assertion, sometimes running into extravagances which are impossible to believe. He even writes in a complacent way of how he contemplated his murders before carrying them out. He writes of his time in Paris:

When certain decisions of the court were sent me by those lawyers, and I perceived that my cause had been unjustly lost, I had recourse for my defence to a great dagger I carried; for I have always taken pleasure in keeping fine weapons. The first man I attacked was a plaintiff who had sued me; and one evening I wounded him in the legs and arms so severely, taking care, however, not to kill him, that I deprived him of the use of both his legs. Then I sought out the other fellow who had brought the suit, and used him also such wise that he dropped it.

— The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Ch. XXVIII, translated by John Addington Symonds, Dolphin Books, 1961

Parts of his tale recount some extraordinary events and phenomena; such as his stories of conjuring up a legion of devils in the Colosseum, after one of his mistresses had been spirited away from him by her mother; of the marvellous halo of light which he found surrounding his head[33] at dawn and twilight after his Roman imprisonment, and his supernatural visions and angelic protection during that adversity; and of his being poisoned on two separate occasions.[12]

The autobiography was translated into English by Thomas Roscoe, by John Addington Symonds, by Robert H.H. Cust and Sidney J.A. Churchill (1910), by Anne Macdonell, and by George Bull. It has been considered and published as a classic, and commonly regarded as one of the more colorful autobiographies (certainly the most important autobiography from the Renaissance).[citation needed][32]

Other works

Cellini wrote treatises on the goldsmith's art, on sculpture, and on design.[12]

In the works of others

The following is a list of works influenced by Cellini or that reference him or his work:

- The life of Cellini inspired the French historical novelist Alexandre Dumas, père. His 1843 novel L'Orfèvre du roi, ou Ascanio is based on Cellini's years in France, centered on Ascanio, an apprentice of Cellini. Dumas' trademark plot twists and intrigues feature in the novel, in this case involving Cellini, the Duchesse d'Étampes, and other members of the court. Cellini is portrayed as a passionate and troubled man, plagued by the inconsistencies of life under the "patronage" of a false and somewhat cynical court. That novel was the basis for Paul Meurice's 1852 play Benvenuto Cellini which, in turn, was the basis for Louis Gallet's libretto for Camille Saint-Saëns' 1890 opera Ascanio.

- Rolex chose to name their line of precious metal dress watches after Cellini, with the Rolex Cellini Collection beginning in 1928 and continuing today.

- Balzac mentions Cellini's Saliera in his 1831 novel La Peau de chagrin.

- Cellini was the subject of an eponymous opera by Hector Berlioz, as well as another of the same title by Franz Lachner.[34]

- Cellini's life is the subject of the Broadway musical, The Firebrand of Florence, by Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill.

- The Affairs of Cellini is a 1934 comedy film directed by Gregory La Cava and starring Frank Morgan, Constance Bennett, Fredric March, Fay Wray, and Louis Calhern. The film was adapted by Bess Meredyth from the play The Firebrand of Florence by Edwin Justus Mayer.

- Cellini's life is an occasional point of reference in the writings of Mark Twain. Tom Sawyer mentions Cellini's autobiography as an inspiration while freeing Jim in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Cellini's work is also mentioned in The Prince and the Pauper in Chapter VII: "Its furniture was all of massy gold, and beautified with designs which well-nigh made it priceless, since they were the work of Benvenuto."[35] And in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, chapter XVII, Cellini is alluded to as the epitome of brutal, immoral, and yet deeply religious aristocracy.

- Herman Melville compares his character Ahab, at the captain's first appearance, to a sculpture by Cellini in Moby-Dick chapter 28; "His whole high, broad form, seemed made of solid bronze, and shaped in an unalterable mould, like Cellini's cast Perseus."

- Judy Abbott mentions Cellini's autobiography in Jean Webster's schoolgirl romance novel Daddy-Long-Legs.

- In Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables, Marius's chapter contains the line "There are Benvenuto Cellinis in the galleys, even as there are Villons in language."[36]

- The Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí was also highly influenced by the life of Cellini, centering many etchings and sketches around his stories and passions.

- Cellini's autobiography is mentioned several times in Muriel Spark's Loitering With Intent.

- Lois McMaster Bujold loosely bases the character Prospero Beneforte in her 1992 fantasy novel The Spirit Ring on Cellini and his works.[37]

- The American poet Frank Bidart studies Cellini in "The Third Hour of the Night", a long poem from his 2005 book Star Dust.

- Ian Fleming mentions Cellini multiple times in his James Bond novels. In the second James Bond novel, Live and Let Die, the villain Mr. Big says that he wishes his crimes to "be a work of art, bearing my signature as clearly as the creations of, let us say, Benvenuto Cellini."[38] In the seventh James Bond novel, Goldfinger, Bond says of the titular villain: "... Goldfinger was an artist - a scientist in crime as great in his field as Cellini or Einstein in theirs."

- Fictional works by Cellini feature in Agatha Christie's The Labours of Hercules, in Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Rappaccini's Daughter"; and the film The Girl from Missouri (1934).

- In The Medusa Amulet by Roberto Masello, (Vintage 2011), Cellini creates the menacing Medusa Amulet.

- Evelyn Anthony's The Poellenberg Inheritance (1972) features the fictional Poellenberg Salt, inspired by the Saliera.

- Cellini is mentioned in George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London as reminding the protagonist of a waiter as a good fellow when one got to know him.

- The fictional secret agent, Nick Carter, owns a pearl-handled, 400-year-old stiletto said to have been made by Cellini, which is featured regularly in the Nick Carter-Killmaster series of novels.

- The 1966 film How to Steal a Million focuses on Audrey Hepburn's character's attempts to steal back a fictional statuette of Venus supposedly sculpted by Cellini before art conservators at the museum it has been lent to discover that it is a fake, actually sculpted by her grandfather.[39]

- Full length drama in four acts A Man of His Time (1923) by Australian playwright Helen de Guerry Simpson 1897-1940 is entirely concerned with Benvenuto Cellini 1500-1571.[40]

- The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles referenced Cellini several times in the second episode of the series as an artist who lived a particularly "wild" life and that his autobiography was entirely unsuited for a nine-year-old boy.

References

- ^ Eve Borsook. The Companion Guide to Florence. 5th ed. Harper Collins 1991.

- ^ The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Columbia University Press. 1994. p. 155. ISBN 0-395-62439-8.

- ^ "Benvenuto Cellini summary". Britannica.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch IX

- ^ a b Rossetti & Jones 1911, p. 604.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch XIII

- ^ "Medallion with Leda and the Swan by CELLINI, Benvenuto". wga.hu.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch XXII.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch XXXVIII

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch XXXIX

- ^ Rossetti & Jones 1911, pp. 604–605.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rossetti & Jones 1911, p. 605.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch LI

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 1, Ch LXXIII

- ^ Robert A. Freitas Jr. (2003). "15.1.1 Mechanical Damage from Ingested Diamond". Nanomedicine. Vol. IIA: Biocompatibility. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience.

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 2, Ch II

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 2, Ch XXXVII

- ^ L. Greci (1930). Benvenuto Cellini nei delitti e nei processi fiorentini (in Italian). Archivio di antropologia criminale. p. 50.

- ^ Rocke, Michael (1996). Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Smalls, James (2012). Homosexuality in Art (Temporis Collection). Parkstone Press.

- ^ a b "Straightwashing von Künstlern - Die historische Forschung tut sich schwer mit Homosexualität". Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF) (in German). 6 March 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c I. Arnaldi, La vita violenta di Benvenuto Cellini, Bari, 1986

- ^ Cellini, Vita, Book 2, Ch. III

- ^ "Cinque anni ha tenuto per suo ragazzo Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano, giovanetto con el quale ha usato carnalmente moltissime volte col nefando vitio della soddomia, tenendolo in letto come sua moglie" (For five years he kept as his boy Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano, a youth whom he used carnally in the abject vice of sodomy numerous instances, keeping him in his bed as a wife.)

- ^ Vita, Book II, Ch. LXXI

- ^ For a graphic restitution of the Golden Gate, see Thomas Clouet, "Fontainebleau de 1541 à 1547. Pour une relecture des Comptes des Bâtiments du roi", Bulletin monumental 170 (2012), pp. 214–215 (english summary).

- ^ James Fenton (4 October 2003). "James Fenton on the history of a recently rediscovered Cellini bronze satyr". The Guardian.

- ^ "Satyr (Getty Museum)". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles.

- ^ Cellini, B. The Autobiography // Gutenberg.org., Vol. II Ch. LXIII, as translated by John Addington Symonds, (URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4028 date of request January 6, 2015).

- ^ Spectacular reopening of the Kunstkammer Archived 24 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Kunsthistorisches Museum

- ^ a b Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham (1985). Cellini. Abbeville Press. OCLC 681620188.

- ^ a b Maryon 1971, p. 286.

- ^ This is a known optical physical effect, called heiligenschein.

- ^ Leuchtmann, Horst (2001). "Benvenuto Cellini". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 14 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 96.

- ^ Twain, Mark (28 February 2017). The Prince and the Pauper. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781365790935. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

- ^ Bujold, Lois McMaster, The Spirit Ring, ISBN 0-671-57870-7 (Author's Note)

- ^ Fleming, Ian (1954). Live and Let Die. Las Vegas: Thomas & Mercer. p. 71. ISBN 9781612185446.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (15 July 1966). "Screen: 'How to Steal a Million' Opens at Music Hall; Audrey Hepburn Stars With Peter O'Toole 'Enough Rope' Arrives at Little Carnegie". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Trove".

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael; Jones, Edward Alfred (1911). "Cellini, Benvenuto". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 604–606.

Further reading

- Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Symonds translation at Project Gutenberg

- López Gajate, Juan. El Cristo Blanco de Cellini. San Lorenzo del Escorial: Escurialenses, 1995.

- Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Cellini. New York: Abbeville Press, 1985.

- Parker, Derek: Cellini. London, Sutton, 2004.

- Andreas Beyer: "Benvenuto Cellini: VITA/Mein Leben", in Markus Krajewski/Harun Maye (Ed.): Böse Bücher. Inkohärente Texte von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart, Wagenbach Verlag, Berlin 2019, pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-3-8031-3678-7

- Angela Biancofiore, Benvenuto Cellini artiste-écrivain: l'homme à l'oeuvre, Paris, L'Harmattan, 1998

- Maryon, Herbert (1971). "Benvenuto Cellini". Metalwork and Enamelling (5th ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-22702-2.

External links

- Works by Benvenuto Cellini at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benvenuto Cellini at the Internet Archive

- Works by Benvenuto Cellini at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Benvenuto Cellini on Scultura Italiana